Last Wednesday's groundbreaking for the 5.5-mile Rail-to-Rail walk/bike path that will run between Metro rail stations at Crenshaw and Long Beach Blvd. along the blighted Slauson rail right-of-way (ROW) was long overdue.

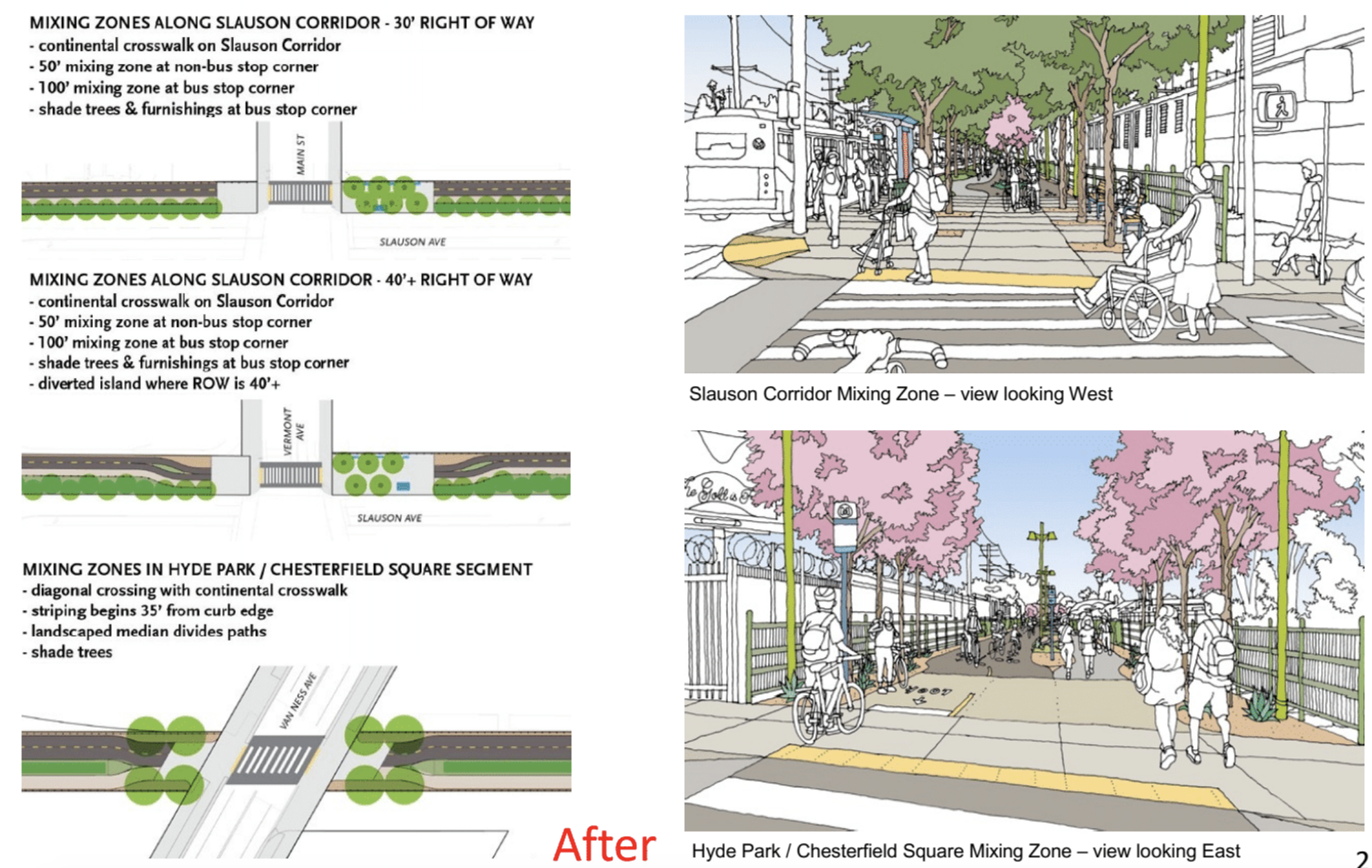

Construction on the path, which will feature shade trees, drought-tolerant landscaping, lighting, improvements at bus stops, and improved crossings at intersections (seen above), was originally expected to have begun in 2018.

But as many of the area’s representatives noted during their celebratory remarks, they had been waiting for something to happen along the corridor for much longer than that.

It was nearly thirty years ago, while serving as Executive Director of the California Black Women’s Health Project (CABWHP), that current County Supervisor and Metro Boardmember Holly Mitchell said she had first been approached by residents about the possibility of a rails-to-trails project for the corridor.

The women that came into her office were concerned about how Black women’s disproportionate experience with obesity and asthma was being compounded by the lack of access to gyms or outdoor spaces where they could exercise.

“I will never forget the residents of that housing development [at 49th and] Central Avenue [where CABWHP was located] who told me quite frankly, ‘You want me to walk. But it is less safe for me to walk the streets in my neighborhood than to sit at home waiting for a heart attack to happen,’” Mitchell recalled.

The fact that that state of affairs remains a “harsh reality for far too many Angelenos” meant this project was “a dream deferred for far too long," she said.

Her sentiments were echoed by Eighth District Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson and Inglewood Mayor James Butts, both of whom recalled being struck by how profoundly disinvestment had marked the community as youth. Butts, who was born in the area in 1953, explained, “At that time, there was the Sears and there was an animal hospital somewhere in here, and those are the only two buildings that weren’t blighted.”

“This is where the train ran,” Butts said of the ground where he was standing. “And then when the train didn't run anymore, [the corridor] was just ignored,” leaving him to wonder just how long the city would allow it to remain that way.

“Well," he concluded, "I found out it was until 2022.”

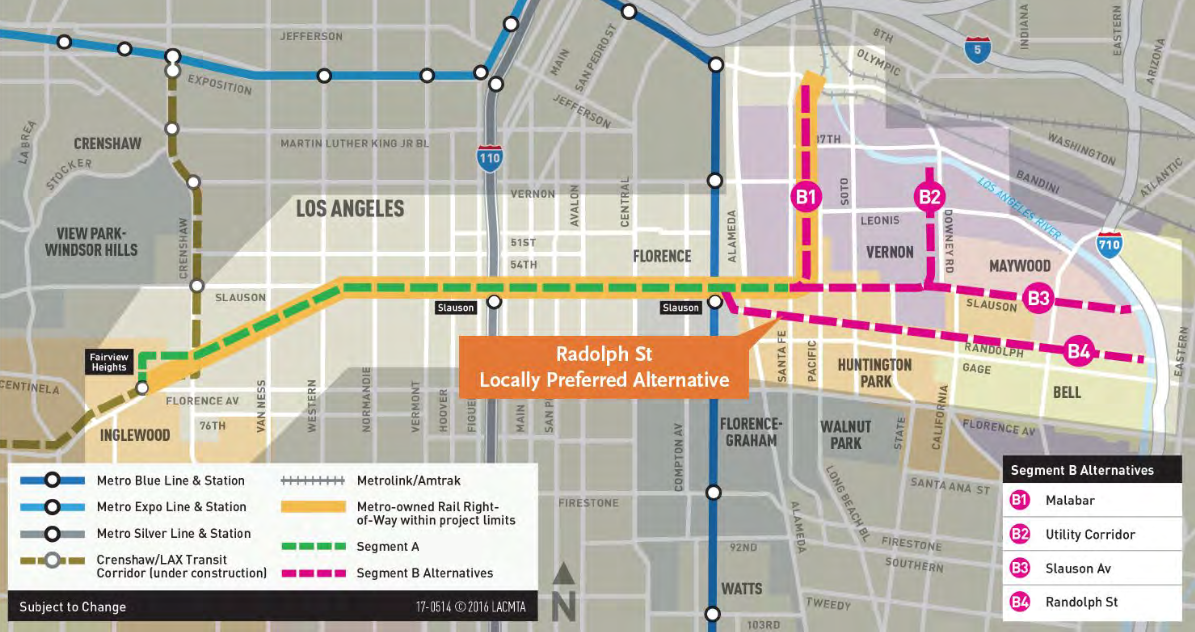

First proposed in 2012 by then-Metro boardmembers Mark Ridley-Thomas and Gloria Molina, the project was initially conceived as a way to convert a ROW deemed infeasible for passenger rail into a community asset in an intensely park-poor section of South and Southeast Los Angeles.

Money for that kind of investment in historically disenfranchised communities isn't that easy to come by. But by framing it as an “active transportation corridor” project – a conduit along which bike and pedestrian commuters could more easily connect to key rail and bus lines – the proposal could be pushed through Metro, making it eligible for a number of federal and state grants.

It still took some convincing to make Metro believe such a project was within their purview, however, said Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins and others during their remarks.

“When Fernando Ramirez came to [Metro] on behalf of Supervisor [Ridley-Thomas],” said Wiggins, “real talk, we were like, ‘What? We don’t do this. This is not us. What is this?’”

To be fair, the project Ridley-Thomas’ office had envisioned was no small undertaking: a green ribbon over eight miles long that spanned the breadth of South Central and eventually made its way through some of the Southeast cities to the L.A. River (above).

Complicating things was the fact that, although Metro already owned the ROW along Slauson, it would have had to negotiate for rights to the ROWs along the proposed routes through the Southeast cities, significantly boosting both the potential costs and timeline of the project.

But Ramirez had been persistent, agreed Wiggins, Harris-Dawson, and Metro boardmember Jackie Dupont-Walker, making converts out of all of them.

Though elected officials and the board subsequently threw their support behind the project, it quickly became clear that the project was pushing Metro well out of its comfort zone.

Early on, Metro did little in the way of outreach to the surrounding community. More than one staff member suggested at the time that the lack of outreach was due, in part, to not wanting to get people’s hopes up for a project that might not come to fruition.

While it is indeed true that South Central has seen too many groundbreakings go nowhere, Metro's reluctance to do meaningful engagement seemed more rooted in the concern that the community's asks would go beyond what Metro could (or knew how to) offer.

Active transportation grants were about moving people from place to place - connecting them to transit and to opportunity while improving bike and pedestrian safety.

Important as that is along a busy corridor like Slauson, the grants would not fund the kinds of features that would also make it a more welcoming site of recreation for area residents - exercise equipment, murals, seating areas, play areas for children and families, activity programming for youth, special spots for the street vendors that had worked the corridor for years, etc.

At the time, the disconnect stoked concerns about gentrification among residents and vendors (many of whom also lived in the surrounding neighborhood). Neighbors said they were desperate for a place they didn't have to drive to or take a bus to to enjoy. If this project wasn't going to be responsive to their aspirations or uplift the way they used public spaces, they wanted to know, then who was it for?

In more recent years, as costs for this segment of the corridor ballooned from a projected ~$19 million to an whopping $143 million, Metro did find itself leaning more heavily on community collaborators, including TRUST South L.A., Brotherhood Crusade, Slate-Z, and the elected officials in the area.

Together, as noted by Zahirah Mann, President and CEO of Slate-Z, they were able to acquire much-needed city, state, and county funds that would also allow for the expansion of the scope of the project to include climate-related goals, like reducing greenhouse gases, mitigating heat islands, and treating rainwater runoff.

But concerns about gentrification remain pressing, especially with the significant growth in housing construction along the soon-to-open Crenshaw Line and visible turnover creeping southward, most notably from the USC/Exposition Park area.

While a bike project in and of itself is not necessarily a catalyst for gentrification, the fact that such projects tend to arrive after an area has begun to see turnover, tend not to acknowledge or engage the wider set of barriers Black and brown community members face in trying to access the public space, tend to be prioritized while other long-standing community asks go unanswered, and can invite a law enforcement presence that is hostile to the existing community means such a project can accelerate the process by which Black and brown folks are made to feel unwelcome in their own streets.

That can leave historically disinvested communities to face a "Sophie's choice," as Mitchell put it, “between blighted infrastructure and dignified healthy spaces that we deserve" but may not be able to enjoy in the long run.

One way that officials have tried to address that dilemma has been by ensuring that infrastructure projects were explicitly reflective of the community.

When Metro decided to run the Crenshaw Line above ground up the spine of the last Black business corridor in the city, for example, Harris-Dawson proposed Destination Crenshaw. The open-air “People’s Museum” honoring Black stories, culture, and contributions is an effort to “turn insult into opportunity,” as Harris-Dawson has put it. And to ensure those passing through are aware they are in a historic Black community. Sankofa Park, the interactive monument to the Black community’s past, present, and future currently rising near the Leimert Park station, might be the most poignant manifestation of that response: Metro had originally planned to bypass Leimert Park Village altogether, only relenting in 2013 after a long campaign led by Ridley-Thomas.

The project is also an effort to harness the inevitable change the Crenshaw Line will bring, though that is a much more difficult undertaking. Promoting local hire and finding ways to support legacy businesses, as Harris-Dawson’s office is doing, is easier than getting developers to provide housing that would be accessible to the community (though Harris-Dawson said his office has also pushed for new construction to have more affordable units, as well).

That South Central is wrestling with these challenges more often these days is a sign of how quickly things are changing.

Metro boardmember Jackie Dupont-Walker recalled how difficult it once had been to attract any kind of investments to the community. Ward EDC, her community development corporation, had been part of the team behind the Chesterfield Square retail center groundbreaking at Western and Slauson back in 2000.

"That was the first economic development project brought back to this area" after the 1965 uprising, she said.

The hundreds of jobs that project created were vital to boosting economic well-being in the community. And the people had been ready for it, she said, recalling that the first person in line for the job fair that day was a formerly incarcerated gentleman who was excited an employer might finally take a chance on him.

Several officials noted that the local hire component for the new path and other community-serving projects should also deliver a boost to area residents. While ticking off a list of projects planned for the corridor, Ninth District Councilmember Curren Price declared his intention to require as high as 70 percent local hire both on the Slauson Connect project (a "resiliency hub" at Slauson and Normandie that will be home to a community center, childcare center, afterschool programs, vocational training opportunities, a new rooftop garden, and a two-acre linear park) and on an affordable housing project at Slauson and Wall.

For her part, Mitchell reiterated her commitment to ensuring that the County and Metro used the tools at their disposal (e.g. the recently adopted land banking policy and Metro's joint development policies and business support programs) to mitigate displacement, center community ambitions, and generate quality green jobs "so we can grow old, exercise with dignity, and our children can thrive" in place.

Dupont-Walker concurred, saying, "Our challenge is going to be to keep a space for the people who fought hard for this... [Because] what we don’t want is for people to be driven out."

But she was also aspirational, speaking of the existing potential within the community to heal itself, when given access to the right tools. Pointing toward King Solomon's Village, the soon-to-open long-term shelter for the unhoused a block over on Slauson, she spoke about how planning for the permanent housing component of the project was still being finalized. Could the project evolve into "a combination home-ownership/rental" opportunity for those ready to take such a step?, she mused. Or could it create "live-work possibilities for people who want to start a dream and a vision who come out of a shelter environment? How wonderful would it be for someone to come out of the shelter and move into home ownership in this area" - and feel able to contribute to the home they were now invested in.

Dupont-Walker had originally joined the Metro board after Mayor Eric Garcetti had convinced her that there was an important nexus between community development and transportation and that it could be leveraged to address some of the city's broken promises to South Central.

Determined to hold the city to this particular promise, she invoked the heavens, pointing to a fig tree and noting its sacred symbolism to the Hindu, Christian, and Buddhist faiths. "I am ordaining at this moment that we will protect that fig tree," she said. "...[It] will stand symbolically as the enlightenment - the restoration of this community - which will just be a symbol of what will happen to the rest of South Central Los Angeles."

"And I did say 'South Central,' not 'South L.A.'," she winked. "Thank you."

_______________

Preparatory work for the project has already been underway for some time. The project is expected to be completed in late 2023/early 2024. See the most recent updates and renderings from Metro at this link (see the community meetings folder). Watch the groundbreaking ceremony on Facebook, here. Learn more about the Slauson Connect project here. See our past coverage below. Questions? Comments? Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman.

- December, 2013: Dear Santa, Please Bring Us an Active Transportation Corridor Along Slauson, but Don’t Forget the Community in the Process (background on the plan; lack of outreach)

- March, 2014: Feasibility Study on Rail-to-River Project Takes Another Step Forward (plan begins to come together; outreach still a major problem)

- October, 2014: Motion to Move Forward on Rail-to-River Bikeway Project up for Vote Thursday (breaks down the feasibility study in more detail, costs, timeline)

- May, 2015: Planning and Programming Committee Recommends Metro Board Take Next Steps on Rail-to-River ATC (more on costs, timelines)

- October, 2015: The Rail-to-(Almost)-River Gets Boost with $15Mil TIGER Grant (yay, actual money!)

- May, 2016: Metro Awards Contract for Environmental Study and Design of Phase I of Rail-to-River Bike Path (OMG it is actually happening; request that outreach finally be meaningful)

- August, 2016: Metro Explores Alternative Rail-to-River Routes Through Southeast Cities (where we learn Metro and the Southeast Cities do not play together well)

- October, 2016: Metro Asks South L.A. Stakeholders: How Would You Use Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path?

- December, 2016: Rail-to-River Route Through Huntington Park, Bell Emerges as Best Candidate; Community Meeting December 8 (The Randolph Street option emerges as the favorite while also the most expensive and most complicated option; Community Advocates demand Metro handle outreach better and incorporate walking into plans better)

- December, 2016: Preview Some of the Design Options for the Slauson Segment of the Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path (self-explanatory)

- January, 2017: Metro Seeks Input on Design Options for Segment A of Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path

- July, 2017: Metro Offers Update on Rail-to-River Bike/Ped Path Design; Project to Break Ground Mid-2018

- December, 2019: Rail-to-Rail Bike/Ped Path along Slauson Delayed but Moving Forward

- February, 2021: Metro Relaunches Rail-to-River Engagement Process to Choose New Southeast Cities Route

*editor's note: We corrected the acronym for the California Black Women’s Health Project from CBWHP to CABWHP. We regret the error.