Metro adopted its Equity Platform in 2018. Metro summarizes the platform as "Transportation infrastructure, programs, and service investments must be targeted toward those with the greatest mobility needs first, in order to improve access to opportunity for all." The policy has led Metro to do equity assessments of its agenda items, projects, budget items, etc., to help guide Metro decision-making.

It's great and much-needed that Metro, L.A. County's primary freeway builder, is assessing how its projects impact equity. The intentions are good, but some of the analyses are lacking.

Equity can be complicated. It's not just what's in a project, and where a project is located, but whom a project serves.

A lot of Metro's equity analysis focuses on location. Metro has mapped Equity-Focus Communities - EFCs - low-income communities of color that are underserved. But just focusing on location can be tricky. Just because a transportation investment is made in a given location, doesn't mean it serves the residents living there. A bus lane project in a well-off L.A. neighborhood is likely to serve working class bus riders, especially folks who work there and live elsewhere. Freeway projects have long displaced, divided, and demolished low-income communities in order to benefit more well-off drivers residing elsewhere.

Many of Metro's equity assessments appear perfunctory, like checking a box. Occasionally they are misleading, for example, when Metro implies that advancing equity means building freeway projects in communities of color.

These shortfalls are in evidence in a new Metro equity assessment document.

At the July 19 meeting of the Metro Planning and Programming Committee, after pointing out that Metro staff had provided equity assessments for transit and active transportation projects, County Supervisor Hilda Solis asked that they do the same for Metro's freeway projects. Staff provided the requested highway projects equity assessment report last week.

Under pressure from state mandates and from its own board, Metro is slowly shifting its approach to freeway expansion (reducing demolitions, including some minor transit/bike/walk project components), but last week's report is mostly a throwback to prior decades of Metro pushing lots of freeway widening.

Perhaps what's most telling is what's not in the report.

Until 2021, Metro freeway building practice had been that more freeway lanes often just meant tearing down lots of homes, apartment buildings, retail, schools, parks, and more. Metro and Caltrans tore out hundreds of homes to widen the 5 Freeway, dozens of homes for under-construction 71 Freeway widening, approved demolitions to widen the 91, and planned hundreds more demolitions including along the lower 710 and the 605 where widening included razing homes along the adjacent 5 and 60 Freeways.

Since 2021, Metro mercifully made a shift away from demolishing homes. Community pressure and federal Clean Air law killed Metro's lower 710 widening. Metro backed off demolishing the 91 Freeway and 605/5 Freeway homes. (Metro is still pushing to evict one Pomona family in the way of widening the 71.)

Right now, Metro freeway building practice seems to be: it's OK to encroach on parks, schools, public golf courses, businesses, lots of "slivers," but no more residential tear-downs. It's a welcome respite. Historically, residential demolitions have been the most harmful aspect of freeway building. But it's not the whole picture.

Metro's de-facto practice is now: as long as there aren't home demolitions and there is a meager outreach process, then a freeway widening is good for equity. This narrow thinking has made its way into Metro equity assessments.

Relying too heavily on no-residential-demolitions as a litmus test fails to take into account other major harms of freeway expansion. Just because a project doesn't demolish homes doesn't make it good for equity. One big non-negative doesn't equal positive.

Metro equity assessments largely fail to account for how to improve mobility for "those with the greatest mobility needs": low-income Angelenos. Nor do the assessments take into account how to improve the air that low-income communities breathe.

Billions of Metro dollars spent to expand freeways benefit Angelenos well-off enough to afford a car, with no mobility benefit (and often adverse impacts) for folks who depend on transit. Freeway expansion induces more driving, meaning worsening air pollution in pollution-burdened low income neighborhoods that already bear the brunt of the basin's unhealthy air.

SBLA will spare readers a blow-by-blow annotation of the new Metro equity assessment document. Most of it is boilerplate rationalizations, listing no adverse impacts of Metro freeway expansion, and asserting projects will advance equity by benefiting "all users of the road" and "commuters of all income levels." The report outlines no residential acquisitions, modest multimodal project components (some of which don't exist), bilingual outreach processes (which Metro sometimes cuts short via environmental clearance loopholes), and whether projects are located in EFCs (though not whether widening a freeway through an EFC is harmful or beneficial for an EFC).

But one project's justification sticks out as especially egregious and just plain false.

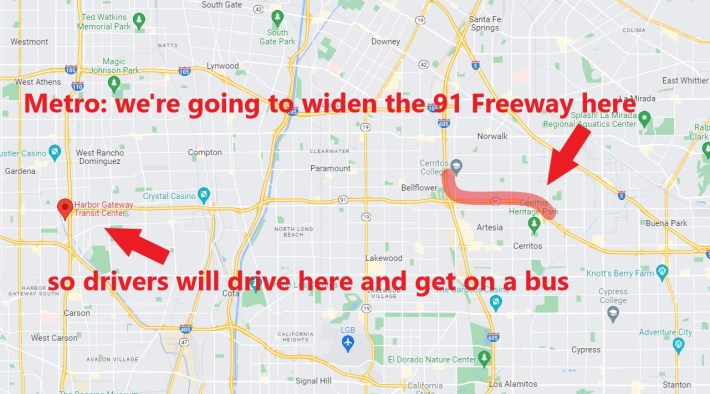

For Metro's $200 million 3.5-mile westbound 91 Freeway widening through the southeast L.A. County cities of Artesia and Cerritos, Metro's equity assessment claims the project will result in "improved air quality" via a tenuous, frankly ridiculous mechanism.

Metro's equity assessment claims that 91 Freeway improvements will get commuters more quickly to connect to "the vast transit network" via the Artesia Transit Center. (In 2011, Metro renamed that busway station park-and-ride facility, now called the Harbor Gateway Transit Center.) The Transit Center is eleven miles west of the 91 Freeway widening, but Metro asserts that widening the 91 would "provide better access to the larger transit system" leading to "increased access to bus lines and resulting improved air quality."

There may be reasons to widen the 91, but no one with a straight face can honestly claim that this project will result in increased bus ridership or cleaner air.

Part of charting an equitable and sustainable future is to be clear about project impacts - both benefits and costs. Too often Metro appears to be in denial about the significant harmful impacts of its own highway expansion. And too often Metro claims dubious highway expansion benefits, then spends years and decades pushing harmful projects - in the face of community resistance.

Metro needs to refine its equity analyses. The agency needs to be clear and honest about project harms, and weigh those negatives against project benefits. The agency's current equity assessments fall woefully short of this, and call into question whether Metro is truly committed to advancing equity.