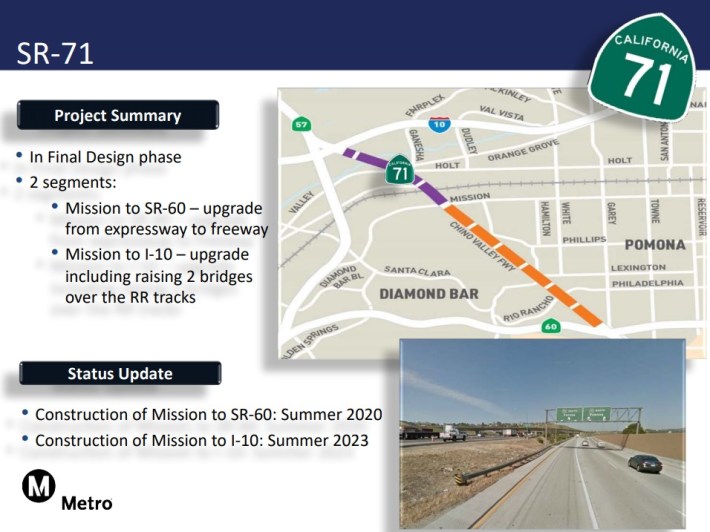

Last month, Caltrans and Metro celebrated a virtual groundbreaking for the widening of State Route 71 through Pomona. The four-lane expressway is being widened into an eight-lane freeway. Construction is underway on the initial nearly two-mile $174 million segment, anticipated to be completed in 2024. Though the project is led by Caltrans, it is funded in large part by Metro county sales tax revenue.

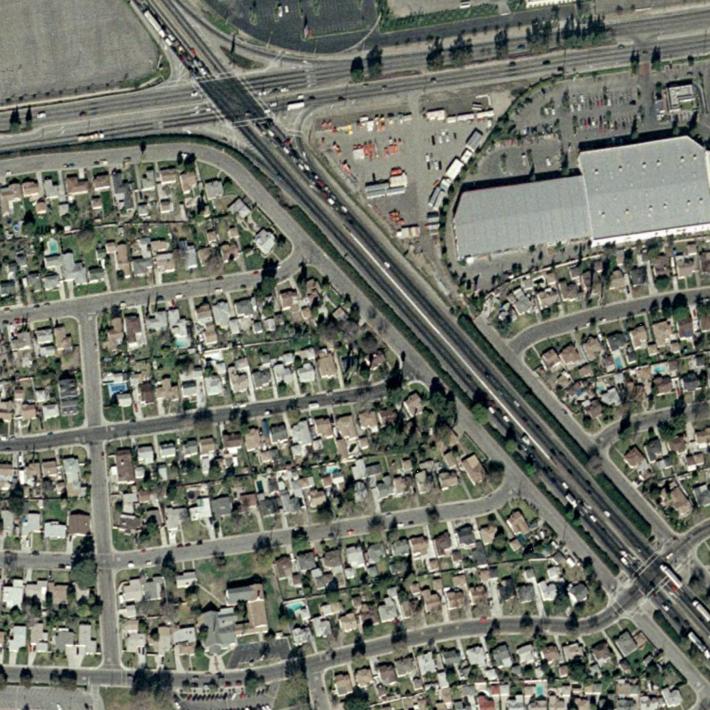

Some SR-71 construction is already underway. Caltrans has closed a couple of at-grade entrances along the southbound side of the highway. In the southern end of the current segment, grading is already underway on both sides of the freeway.

In the southern portion of the project, in the newer Phillips Ranch neighborhood, there is existing vacant right of way where the 71 is to be widened.

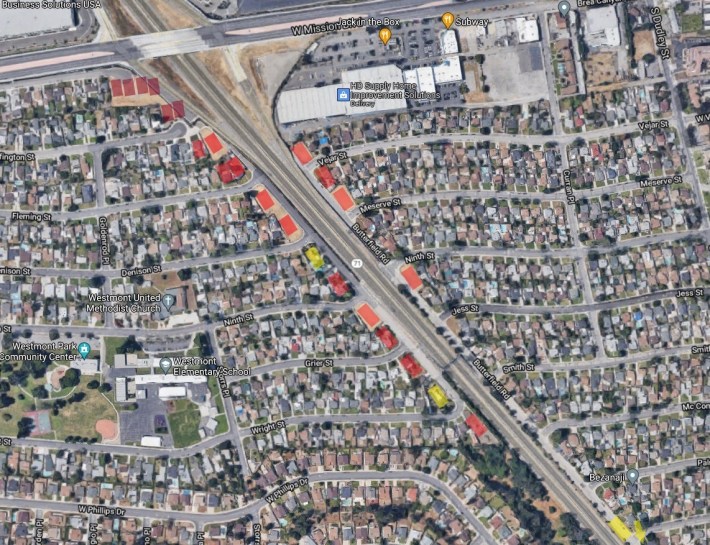

Just to the north, Pomona's Westmont neighborhood is not so lucky. Westmont is a neighborhood of single-story single-family homes west of the 71. The community is predominantly homeowners, mostly Latino, though with significant numbers of other ethnicities - mainly white and Asian - also residing there.

Since 2019, Caltrans has been acquiring and demolishing homes along the SR-71 in Westmont - as well as some on the east side of the highway. More than a dozen homes have already been torn down, but there are still a couple of families holding out against the agencies' home demolition plans.

Where single-story homes had stood since the late 1940s, more than a dozen lots are now weedy fenced-off vacant lots.

Eric Duran has lived in Westmont for more than a decade. He was first approached by Caltrans in 2018 and told he would have to move out. Duran was in the process of remodeling and upgrading the kitchen at the time. A Caltrans representative told him to stop working on the house. Though Duran soon finished the remodel (so his family would have a working kitchen), a Caltrans appraiser described his home as being in a "deplorable state" due to the then-unfinished renovations.

Today, Duran's is one of two remaining Westmont families still living in homes threatened by Caltrans.

Duran relates that the process has already been stressful. Starting in 2018, he says, Caltrans representatives "came with the attitude 'We got the power.'"

"They would stop by people's houses unannounced," Duran notes, and "they didn't provide a translator" when urging Spanish-speaking residents to sign papers in English. Duran has reviewed Caltrans Right of Way Manual and contends that Caltrans has not properly followed their own procedures.

Just last week, Caltrans informed Duran that the home where his family lives was sold to Caltrans. Duran is caretaking and improving the home, which was owned by an elderly co-worker. Per Duran, the home where he lives had been in an extended Escrow since late 2020. Caltrans is now his landlord.

Since 2018, most of Duran's SR-71-adjacent neighbors have already left the neighborhood.

Eli Acosta, a 72-year-old retired home painter, had been Duran's neighbor, but relocated to Ontario, CA, in 2019.

When Caltrans approached Acosta to relocate, he requested a delay as he was on a waiting list for an urgent liver transplant. Soon after his transplant operation, Acosta relates that Caltrans representatives continued to visit his home, urging him to sign paperwork. He states that he told them "I don't want to sign - I can't even walk," to which they responded, "If you don't sign, I will foreclose immediately."

After prolonged pressure, Acosta and his wife decided to relocate to their current two-story home. His elderly wife is unable to climb stairs, so they discussed the installation of a stair lift with Caltrans. Acosta states that a Caltrans representative verbally agreed that the agency would pay for the medically-necessary lift. After Acosta spent $11,000 installing the stair lift, Caltrans refused to pay for it. Acosta went through an appeals process, but to this day maintains that Caltrans lied to him and his wife about the lift.

Both Acosta and Duran state that many of Caltrans' offers were lower than properties were worth. Their end of the block lots are larger than the mid-block lots that Caltrans had cited as comparable. Similar lots are very difficult to find, relates Duran, so most of his neighbors ended up in smaller homes that were more expensive than the ones Caltrans demolished.

From historic photos, two remaining sites, and residents' accounts, the end lots were (and still are) very desirable. The well-tended small homes sat among yards full of mature trees, including many fruit trees. Acosta has planted sapling fruit trees in the front yard of his new smaller Ontario lot, but misses the mature trees he left behind, which he states were not included in Caltrans' appraisal.

Acosta feels that Caltrans "took a lot of property they don't really need," suggesting that Caltrans may be focused on more widening in the future, not the just the minimum needed for the present project.

Caltrans' is demolishing at least 18 homes, when their approved widening plan only called for around 12.

In 2013, Caltrans approved a 2013 Supplemental Project Report (SPR) that amends the SR-71 Project Report approved in 2002. The 2013 SPR states that right of way impacts, from Mission Boulevard to Old Pomona Road: "There are 26 properties... impacted by the freeway widening in this segment. Approximately 12 units will be full parcel acquisition."

Just after Measure M was approved in 2016, Metro spokesperson Kim Upton stated, "It’s still not known if the project will require acquiring any homes to make way for the freeway, and that won’t be known until after the design process is completed." When demolitions got underway in 2019, Caltrans had already upped their total to 17, claiming that, "12 of the single family residences have been purchased or are near closing Escrow. The remaining five homes are pending settlements with negotiations well underway."

Today, Caltrans has already demolished 15 homes, with three additional homes still under threat of demolition. (This is in addition to the six Westmont homes Caltrans demolished earlier - prior to 2013 - to make way for the Mission Boulevard Bridge.)

Both Duran and Acosta recounted the tragic story of their neighbors Rudy and Gloria Ramos.

Gloria and Rudy Ramos, both age 78, had lived in their Westmont home for more than 30 years when they received word from Caltrans, in mid-March 2018, that they would need to relocate.

Their daughter, Rebecca Ramos, and her husband contacted Caltrans, urging them to "be more considerate to the elderly" and to leave their "very fragile" parents alone - and requested instead to go to Rebecca and her husband for negotiations regarding the Ramos family home.

Caltrans continued to visit the elderly couple's home, while Rebecca began to make arrangements for her parents to move into her home nearby.

Rebecca Ramos described Caltrans as having "harassed" her parents, dropping by frequently. She recalled that neighbors told her about her mother shouting curses, "¡cabrones!" at Caltrans representatives, telling them to get off her property.

Acosta recalled that his wife and Gloria Ramos both fell into serious depression about the prospect of Caltrans forcing them to leave their homes.

On April 11, Rebecca Ramos arrived at her parents' home, expecting to eat dinner with them. She discovered her parents dead, lying next to each other in their bed.

According to a Pomona Police Department spokesperson (as reported by the L.A. Times) Rudy Ramos was shot by his wife. Gloria then shot and killed herself. “They may have been distraught over having to sell their house [for the freeway expansion], because they lived there all their lives... We haven't confirmed that, so right now we can only assume they were upset about possibly losing their home."

Rebecca Ramos spoke of the trauma and hardship of burying two parents at once.

She harbors deep resentment toward Caltrans for her parents' deaths, as well as for what followed.

Rebecca never got the apology she felt she deserved. Despite TV news coverage at the time, Caltrans acted like "they didn't even know" about her parents deaths. The Caltrans right of way agent that Rebecca had been interacting with essentially disappeared, and Rebecca was shunted off to Caltrans' lawyers. Throughout the settlement process over the home, Caltrans never acknowledged any role in her parents' deaths.

Even after signing the home over to Caltrans, Rebecca was hit with unanticipated large property tax bills.

Prior to Caltrans taking the home, it had been vandalized, so Rebecca had arranged for a tenant to rent the home. Caltrans soon went "behind our back," she said, paying the tenant to turn over the keys and leave the home.

Rebecca Ramos spoke of her father as very outgoing, "always talking to neighbors," and "super-invested in the Westmont community." He was "loved by everybody in the neighborhood." He would "bike around the neighborhood in the morning," checking in with his daughter and son, who both lived nearby. Her mother had been similarly involved until suffering from back problems.

"All those memories knocked down," Ramos said, and "Caltrans won't admit wrongdoing."