Among transit projects in the Los Angeles area, none is perhaps more important, nor as heavily disputed as the Sepulveda Transit Corridor project. The Sepulveda corridor is one of the heaviest trafficked corridors in the United States, with the 405-freeway providing a vital linkage between the San Fernando Valley and West Los Angeles. Metro’s Sepulveda will ultimately link the San Fernando Valley with Santa Monica and LAX.

Recently, Metro approved an automated heavy rail subway alternative, which will connect with the Van Nuys Metrolink station, the Metro G Line, the future Metro D Line extension, and the Metro E line. Earlier subway proposals met some opposition from some community members, including residents of L.A. City’s Bel Air neighborhood, who had backed a monorail alternative.

The Sepulveda monorail was proposed by BYD SkyRail, a Chinese subsidiary of BYD, a Chinese automotive company who have also previously provided buses for the Metro Bus Fleet. Though the monorail promised some benefits, many transit experts remained skeptical–BYD has in the past over-promised and underdelivered in contracts both in Los Angeles and in other metro areas. The monorail also would have introduced new obstacles to planners as Mid-405-Freeway Monorail construction would likely be opposed by the state Department of Transportation, Caltrans.

With Metro’s January heavy rail approval, the Sepulveda monorail alternative is seemingly, finally dead.

However, the Sepulveda Transit Corridor monorail is not the first time that Los Angeles has flirted with - and rejected - the idea of a monorail. Los Angeles is now relitigating a matter that was already settled half a century ago. In 1951, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority, a predecessor agency to the modern Los Angeles Metro, was created with the objective of designing and constructing a monorail for the city of Los Angeles. For more than a decade, the LAMTA navigated the complex technical, political, and socio-economic challenges associated with their monorail. While the LAMTA monorail proposal was never constructed, its history is a useful comparison for the monorail proposal under consideration for Sepulveda, as well as transit projects in the L.A. area more broadly, and why they are often so difficult to implement.

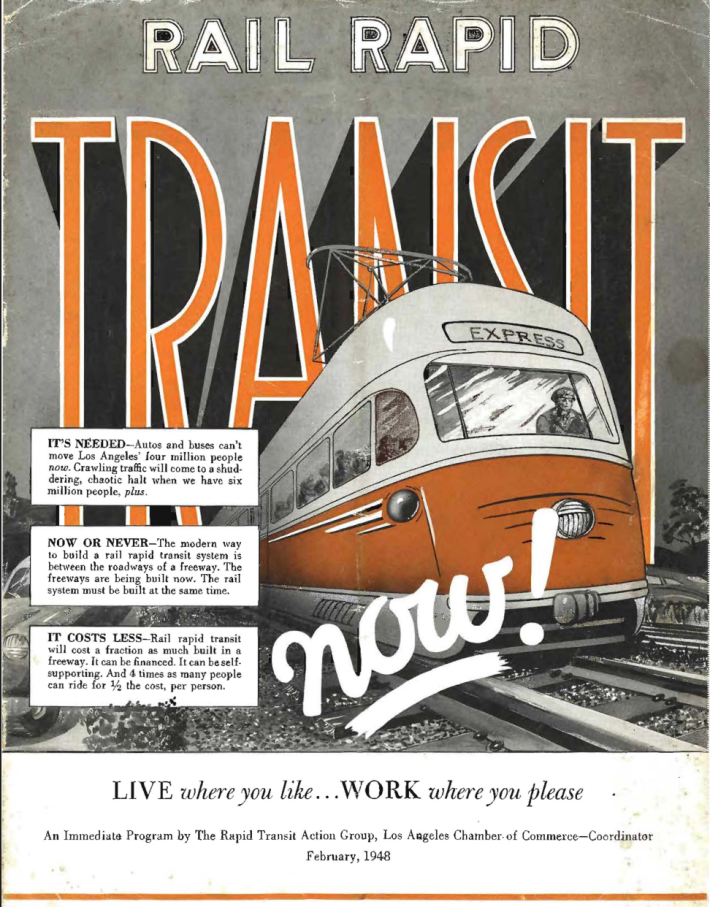

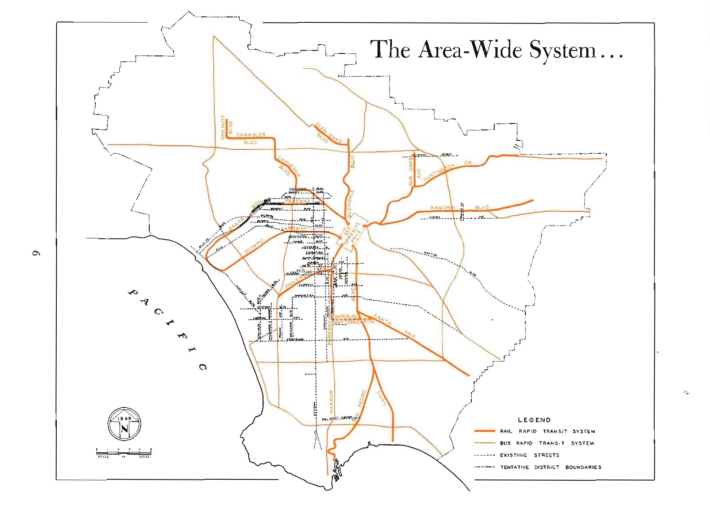

Many of the issues faced by the LAMTA parallel the recent Sepulveda proposal. In 1947, a group known as Rail Rapid Transit Now!, organized by community leaders from the L.A. business community advocated for the construction of a mass transit system servicing the greater L.A. area. Many of the proposals that they suggested would mirror modern L.A. Metro lines today, including the Metro A Line.

Their proposal was rejected, however, by the California State Assembly in favor of a monorail, being promoted by George Roberts. Roberts, like the character of Lyle Lanley from The Simpsons, was a charismatic and exceptionally well-connected individual who convinced the city of LA and the state government that the monorail, a technology he had encountered during his wartime service in Germany, was the future of mass transit. Governor Earl Warren signed legislation into law that created the LAMTA, which was tasked with investigating the monorail.

Roberts secured financial backing for his company, American Monorail, and became close with city planners, however he never was able to demonstrate a working prototype for his envisioned monorail. City officials and Roberts met behind closed doors, sometimes in locations that betrayed their role in servicing the community, including country clubs, and expensive restaurants along Hollywood Boulevard. Roberts was eventually accused of insider trading because of the inappropriate closeness of his relationship with the LAMTA. Scandal eventually drove him out of the project for L.A. but he continued to promote monorails elsewhere, including San Francisco. Other companies such as the German-Swedish Alweg, which also built the Disneyland monorail submitted proposals for a monorail to the LAMTA.

Goodell, a Texas-based company which had only ever built a small scale prototype proposed a too ludicrous to be believed jet-powered monorail that would travel between downtown and LAX at 90 miles an hour. Even Los Angeles based aerospace companies Northrup and Douglas submitted proposals. It had seemed L.A. had become monorail-crazed.

By 1960, however, the LAMTA had already realized that the monorail was impracticable and unworkable for a city like Los Angeles. Internal documents from the LAMTA reveal many of the same lessons that Metro is relearning about the monorail today. Monorails would be incompatible with existing rail, which had a much greater availability of manufacturers and pre-existing engineering knowledge, knowledge which Metro itself has been acquiring over four decades. Monorails were also needlessly mechanically complex--the technology of a rubber-tired monorail, versus a rubber-tired subway were essentially identical, except that a monorail had three times the number of moving parts and thus points for failure. Monorails could not, alternatively, be easily put into tunnels, which was a problem for areas like downtown or Wilshire, where taller buildings and local opposition made above street construction unworkable.

Studies into the German Wuppertal monorail, which had been the inspiration of Roberts (and also Walt Disney, coincidentally) showed that the Wuppertal monorail worked because of extremely specific factors that were unique to the German city of Wuppertal, including the local availability of steel and its unique geography, factors that did not apply to Los Angeles. LAMTA would find that only above the L.A. River would a suspended monorail system work, and such a system would hardly service the city’s commuters. Essentially, any proposed monorail would be a bespoke application for which the LAMTA would be permanently locked into, and which would become incredibly expensive.

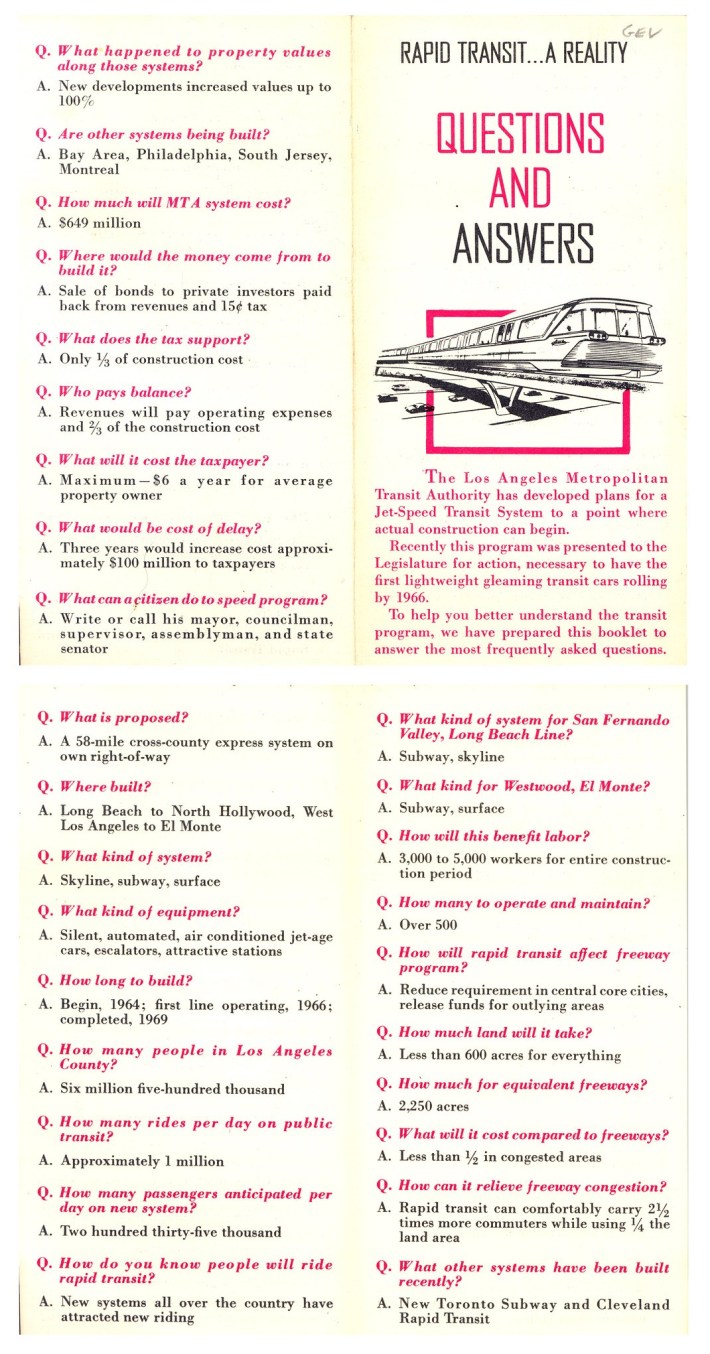

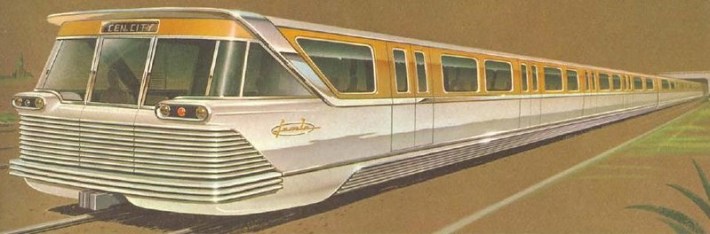

Recognizing these challenges, the LAMTA initially wanted to construct a rubber-tired metro system, like the Montreal or Mexico City subways before agreeing to a proposed traditional heavy rail subway to be constructed by Kaiser Steel. When the LAMTA, however, attempted to pursue funding for the subway in 1962 and 63, the public became outraged by the sudden and seemingly arbitrary decision to pivot away from the monorail. The LAMTA had taken over a decade and built nothing. The monorail had become imagined as a futuristic and distinctly Californian idea. Alweg’s partnership with Disney, and the futuristic styling of Disney’s designers played no-small part in captivating the public.

Science-Fiction author Ray Bradbury, an L.A. resident, became especially outspoken, condemning the LAMTA as a corrupt organization. Bradbury would later in life lament the lack of a mass transit system in L.A., ironically, given his efforts opposing the LAMTA as a contributing factor.

Accusations against the LAMTA as a corrupt organization, however, were somewhat hollow when considering the full details of the monorail’s history. The LAMTA, an organization which was given very little political authority to begin with, functioning at best, as an advisory board, nevertheless took steps that were very much in the public interest. While the monorail may have had the appearance and styling of a train of the future, they were overly complicated and impractical machines which offered no real benefits to conventional rail, and were in most cases, worse than existing rail technology.

LAMTA’s long efforts can be partially attributed to the difficult urban geography of Los Angeles. Its spread has made transit planning difficult, and the scale of planning required had never been encountered anywhere else in the country before. This problem continues to plague transit planners in L.A. today. Moreover, the actions of monorail companies gave many reasons for the LAMTA to become monorail averse. Of the different companies vying to win the lucrative opportunity of government contracts, only two had experience with large scale government contracts and the manufacturing capability to realistically deliver a working system: Northrup and Douglas.

However, perhaps because of their lack of interest in refining their systems, or because of their familiarity with the LAMTA’s lack of authority or financial backing, neither chose to actively pursue bidding. Additionally, while Northrup and Douglas were familiar with government contracts, they were primarily contracted by the Federal Government and for military contracts, designing military aircraft—neither company had built transit before, and the requirements for a contract at a scale such as Los Angeles were bureaucratically different than those of the Federal Government and the Department of Defense, which typically had greater room for cost overruns. Meeting minutes from the LAMTA also reveal that the LAMTA itself seemed uninterested in pursuing an agreement with either company, despite glowing recommendations by Coverdale and Colpitts, the LAMTA’s primary consultant group for engineering advising.

This left LAMTA with contractors who did not have proven track records. These remaining companies, which included American Monorail, Alweg, and Goodell acted in ways that could only be described as distrustful. Robert’s impropriety and insider trading was already one example. But Alweg’s American branch also became increasingly desperate for contracts in the 1960s and submitted several severely underestimated bids to the LAMTA that were beyond the scope of its capabilities. Alweg, a company which had never built a monorail at scale, and which demanded 100% of the operating revenues, had promised that it could build a monorail for Los Angeles that would cost only $140 million, when estimates for subway systems were around $500 million.

Alweg pointed to the Seattle Monorail, built for the World’s Fair as an example of their ability to construct a monorail, but the LAMTA finance office had shown that the Seattle Monorail was only profitable because it was heavily subsidized by admissions tickets to the world fair itself, and that the promised returns from fare-box revenue alone would not be able to cover the ridership costs either for the Seattle Monorail or their proposed monorail from El Monte to Century City.

By the time LAMTA moved away from the monorail, it was already too late. The public was enraged and opinion against the LAMTA had turned negative. A bill was introduced in the California State Senate to abolish the LAMTA and hold it more accountable to the public. LAMTA’s inability to effectively communicate with the public about why the monorail was a bad idea cost the entire region dearly. Even though the LAMTA had managed through considerable difficulty to find a transit solution for Los Angeles, their plans were not implemented for another three decades. The PR fiasco set transit in L.A. back considerably.

Monorails had a distinctly unique flair that captured the public imagination. They seemed like new and futuristic technology. The sleek car body styling was evocative of the automotive industry, and it was hard for the public to let go. Monorails were a promise of the future that never was.

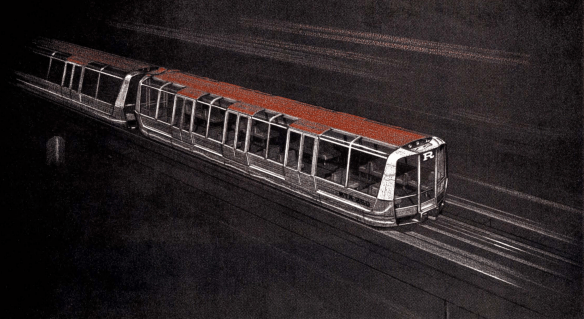

The LAMTA themselves recognized the value of the aesthetic and worked considerably to make public transit romantic. Their subway designs included plans for a new “LA” car, a unique four-door subway car with pinstriping and ends that reflected aerospace design language. But while the monorail itself seemed like the future, its origins were quite old. Robert’s inspiration, the Wuppertal monorail, was built in 1901, and other designs predated it to the 19th century. The monorail is hardly new, nor is it itself any more romantic than any other form of transit.

Metro’s decision to reject the monorail is the correct decision, informed by the logistical challenges that building such a monorail would entail. A monorail as designed simply would not provide the same level of capacity as a heavy rail alternative, nor would it provide the number of transit connections being offered by the automated subway which Metro selected.

Cooper Crane is a public historian studying the history of infrastructure and transportation in Southern California. His current research includes the history of the Los Angeles metro, and the development of infrastructure along the Santa Ana River, the largest river in Southern California. His goal is to imagine sustainable and equitable alternatives and futures for urban environments. He is currently a graduate student of the University of California at Riverside.