This month, the Metro board is scheduled to consider approving the first steps toward a public-private partnership that would build and operate the Sepulveda Transit Corridor Project. The new Metro line would link the San Fernando Valley to the Westside, and ultimately to LAX.

Sepulveda is a mega-project that is only partially funded. Typically, when this is the case for projects, Metro seeks funding from other levels of government - like, say, the pro-rail pro-transit Biden administration. For Sepulveda, Metro hopes that a Public-Private Partnership (P3) might bring private sector money (and financing) to the project.

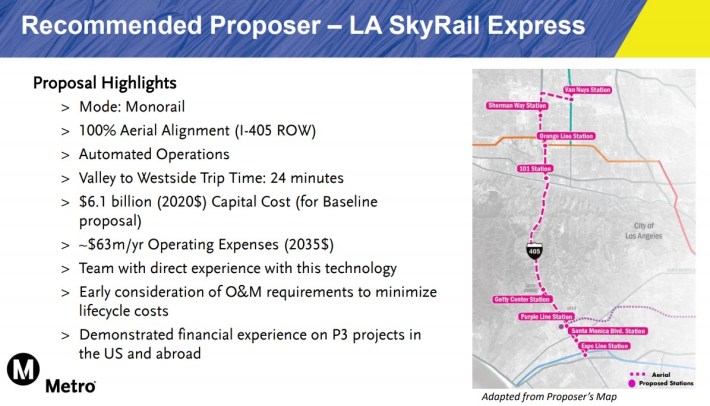

The early phase of the P3 deal is called a Project Development Agreement - PDA. This week, the Metro board Executive Management Committee is expected to approve $63 million contract (staff report) for initial PDA designs to further refine the monorail proposal.

Metro received and evaluated four private sector proposals for the project. The highest ranking proposal is a $6.1 billion monorail down the middle of the 405 Freeway - called the "L.A. SkyRail Express."

How this proposal ranked highly is baffling. It should have been ranked "infeasible."

(For a useful look at the two proposals Metro is considering, see this explainer post at Urbanize. For more information that Metro has shared, see this February staff report and presentation, and the March staff report. Note that the proposed project scopes are not set in stone; Metro expects that the PDA process would facilitate identifying issues, and refining designs further.)

Below are ten reasons not to proceed with any more work on the monorail proposal. (SBLA thanks the L.A. Podcast's Scott Frazier for his Twitter thread outlining several of these.)

1. Caltrans won't allow it

It has been a really rough slog when Metro has tried to build transit improvements in freeway rights-of-way controlled by Caltrans.

After at least ten freeway vehicles crashed into the Metro L (Gold) Line right-of-way in Pasadena, Metro set out to build a crash barrier. For this life-and-death improvement, Caltrans has given Metro the run-around - claiming that non-standard features would block drivers' lines of sight - and tried to keep construction from ever, heaven forbid, temporarily closing a freeway lane.

Metro recently canceled plans that would have extended the Eastside L Line along the 60 Freeway, in large part due to Caltrans' onerous requirements. Caltrans insists on massive buffer spaces along its freeway right-of-way - to ensure that they can keep widening freeways decades from now. These requirements straightjacketed the proposed transit line, increasing costs and decreasing transit speed and utility.

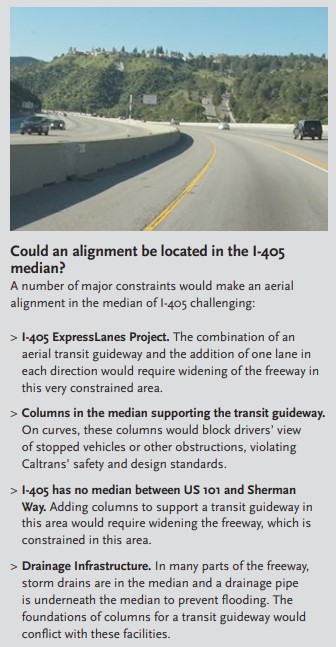

Metro's own 2019 Sepulveda Transit Feasibility Report (page 25) clearly spells out several reasons why the freeway alignment doesn't work:

- Elevated transit needs columns, which would somewhat obstruct drivers' views of the freeway ahead; obstructing drivers' sightlines would violate Caltrans' standards.

- Adding columns in some places - especially in the Valley north of the 101 Freeway - would require widening the 405 Freeway. This would cost billions, and would require demolishing homes and businesses. (For some of that Valley stretch, the monorail proposed would run on the east side of the 405, in the Caltrans right-of-way where Caltrans typically requires a buffer to allow for future widening.)

- The transit infrastructure would conflict with the freeway's existing storm drains and planned Express Lanes.

While it may look quick and cheap to run new transportation in an existing transportation corridor, today in Los Angeles, adding any transit facility to a freeway corridor means that transit rider needs will be secondary to driver needs. Having to get Caltrans approval for every Metro design decision means huge delays, which are also known as huge costs.

Freeway transit stations are 2. Polluted and 3. Loud

With enough time and money, perhaps none of those Caltrans concerns are entirely insurmountable, but what do transit riders get at the end of the day? They get hellishly loud and polluted mid-freeway stations.

Metro already has more than a dozen wretched mid-freeway stations that violate both Metro's own station noise limits and those set by workplace safety agencies. These facilities subject Metro riders to unhealthy uncomfortable unacceptable conditions.

Don't take Streetsblog's word for it. Writing at Metro's official The Source blog last summer, Steve Hymon critiqued Metro's "less than ideal" mid-freeway C (Green) line:

In its own weird way, the C Line has offered another unusual legacy: what not to do when building a transit line. In the case of Metro, freeway median stations have long been out of fashion (although a few would get built) and future projects give stations a much firmer footing in the communities they are intended to serve.

With enough time and money, there are ways to somewhat lessen Sepulveda Line riders' exposure to the pollution and noise from one of the most heavily trafficked freeways on the planet. Places like Seoul build greenhouse-like enclosures around freeway stations to block some noise and pollution, but then this drives up the cost and further obstructs those above-mentioned driver sight-lines.

In some of the renderings, the stations aren't quite in the middle of the freeway; they're just alongside it, but the same hellish conditions apply. The further from the freeway, the better, but veering the mid-freeway monorail over and off of the freeway means increased costs and decreased speeds.

4. Freeway station areas are not conducive to transit and walking

Freeway stations themselves are wretched inhuman spaces (above) but so are the areas around these stations.

Freeways only look like useful locations for transit to the people who don't actually use transit. For the most part, these are the drivers already stuck on those congested freeways.

The proposed monorail map (above) puts seven out of the eight stations at freeways (with more freeway stations if the line is extended to LAX). One is actually labelled "101 Station" because the proposers apparently thought that the massive interchange between the 405 and the 101 is somehow a place that transit riders want to go.

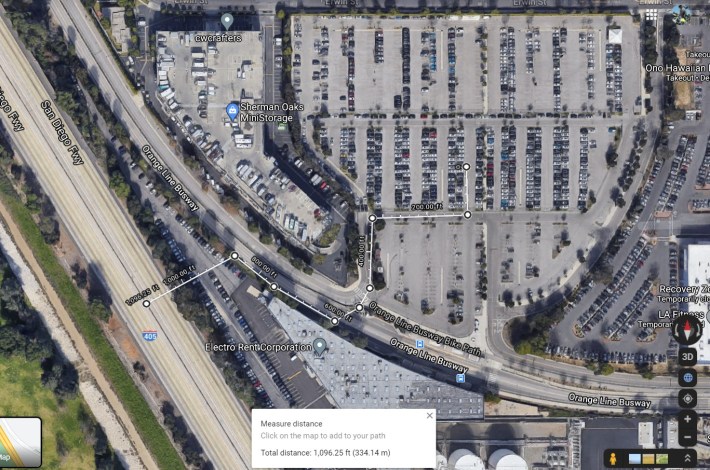

Below is a rendering of the monorail station at the Sepulveda G (Orange) Line - a transfer station between two lines. Many of the criticisms below apply to nearly all the stations.

The angle depicted makes the 405 Freeway hard to spot. The ten-lane freeway is there in the upper third, partially obscured behind the station, elevated tracks, and all the proposed trees.

The rendering dedicates more space to the elaborate pathway to the station than it does the station itself. People driving to and from the station would need to walk roughly 1,100 feet from parking space to monorail platform. People walking to the station... are an afterthought at best.

The station area is typical of areas along freeways; this one is surrounded by a sea of surface parking, plus a parking/storage structure and an industrial building. There is hardly anything worth walking to. There is no housing for people who would ride transit.

This could change in the future, but sites this close to freeways make poor candidates for transit-oriented development - see the noise and pollution points above.

(The rendering also shows the current conditions at the site, ignoring that Metro has already approved construction of an elevated busway, which will elevate the G Line Station and move it eastward.)

5. No UCLA station

Metro's Sepulveda Line designs showed a new station on the UCLA campus. Metro estimated that the UCLA Station would have 17,000-18,000 daily boardings – the highest of any non-transfer station in the Metro system.

Sure, the monorail can slap together some half-assed shuttle that some UCLA students and workers will use, but the line's utility and ridership tank without a direct connection to UCLA.

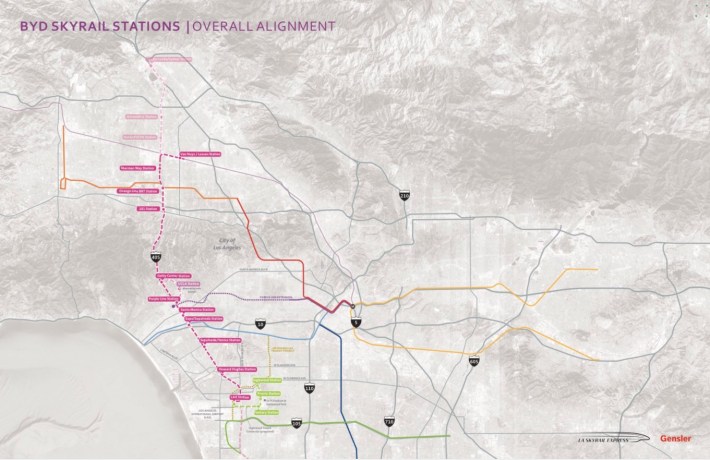

The monorail proposal map (see below) does show a possible dog-leg extension to UCLA, not part of the $6 billion baseline that Metro ranked highly - but an expensive add-on. These sorts of circuitous dog-legs add serious expenses and slow down speeds.

6. Monorail proposers didn't map Metro's existing transit lines correctly

Perhaps this is not crucial for building a Westside-Valley monorail, but it doesn't inspire confidence that the Sepulveda monorail proposal map failed to find the locations of existing Metro transit lines.

The monorail team didn't find the actual location of the Metro L (Gold) Line. The existing Foothill L Line is shown along the Metrolink San Bernardino Line while its actual alignment is farther north. The Eastside Gold Line is shown on a portion of the Metrolink Riverside Line tracks.

This gets even more nitpicky, but there are several more minor mapping errors. The A (Blue) Line appears to terminate at the E (Expo) Line. The A Line through South L.A., the E Line Santa Monica terminus, and G Line Chatsworth terminus are all mis-mapped. Some under-construction rail lines are shown, though the Regional Connector and Foothill L Line are omitted.

(Hat tip to Marshall Alexander Knight commenting on this at Urbanize.)

7. Monorail technology has few upsides

Monorail operations would mean a whole new fleet of Metro vehicles that could only run on this line. For efficiency, training, parts, etc., transit operations work best with fleets of vehicles. Metro has large numbers of basically one type of interchangeable light rail vehicle. When a new light rail line opens and there are delays in new rail cars being delivered, Metro can make up for the deficiency by shifting some cars from one line to another.

If Metro proceeds with its first monorail, it means one more fleet of vehicles to operate and maintain. To some extent, this is a problem with a public-private partnership. Namely, it creates a separate fiefdom designed to be run by a separate private operator, which does not contribute to needed overall redundancies and efficiencies that can help Metro.

Monorails do work. They look cool and futuristic, though they are old technology - nearly as old as conventional rails.

They are not very versatile. When running entirely aerially, monorails can be slightly cheaper than conventional rail. At grade or underground, monorail is typically more expensive. Track-switching is also complicated, hence expensive.

For a helpful run-down on where monorails make sense, see this piece at Greater Greater Washington.

8. Transit P3s have failed spectacularly in other cities

Why do a Public-Private Partnership at all?

Theoretically, the private sector brings innovation, cost-savings, and some sharing of costs and risks.

It's not so clear what the innovation is here. Metro already did too many awful freeway transit stations on its existing lines.

Mark Vallianatos, Executive Officer of Innovation at Metro's Office of Extraordinary Innovation, tweeted asserting that Metro's P3 PDAs "revolutionize travel times" in L.A. using "90-second subway headways." He also states that they will cut costs by four billion dollars.

I didn’t work on the Sepulveda PDAs at all but you also say an idea that came out of them was to revolutionize travel times in LA with 90 second subway headway’s or cut costs for a major project by 4 billion 🤷♂️ https://t.co/oS21njcz2I

— mark vallianatos (@markvalli) March 10, 2021

Metro actually already has this revolutionary innovation. Metro can and should "revolutionize travel times" today - by running very short headways on its rail and bus lines. But the agency chooses not to - primarily to save money in its operating budget. (Many SBLA readers are aware that Metro is moving in the wrong direction with this service frequency innovation - in the past year the agency cut service and delayed restoring it.)

Vallianatos' travel times and cost cuts are related.

To run lots of frequent service, Metro would have to pay lots of drivers/operators, who are unionized. By creating a separate Monorail system run by the private sector, Metro gets around paying workers well. This is, of course, not innovation. It's a tactic as old as paying people for their labor.

If P3 treating workers badly is not enough, there are numerous examples of them serving transit agencies and riders badly, too.

The state of Maryland used a P3 to build its Purple Line light rail project. When costs rose, the private contractor quit mid-construction, resulting in big costs paid by the public agency and big delays in finishing the line. So much for shared costs and risks. Pedestrian Observations documents the Maryland example, and similar P3 failures in Vancouver and Milan. If the P3 fails, then ultimately P-Public is on the hook for the costs that the P-Private couldn't make good on.

P3s can result in a fractured system, where riders can't tell what Metro is responsible for and what the private operator is responsible for.

With P3 build-operate arrangements, Metro cedes control of the system to the private operator - for decades. Metro decisions that impact the private operations can result in Metro having to make up for the private operator's "lost" future revenue (as happened when Chicago privatized its parking.) What shape these complicated P3 contracts would take will ultimately depend on the overall contract, which is still to be determined. But there are lots of Metro decisions that impact operations; these could include charging for parking, eliminating park-and-ride spaces (for example to build affordable housing, a bike path, or scooter parking), banning some types of advertising, and/or cutting service hours on connecting lines. Having a private operator running its own leg of the system can make these sorts of system changes more difficult and more costly.

9. Privatization has already failed L.A. transit riders

Transit riders need look no further than Metro riders' bus shelters for a cautionary tale of privatization. Metro has ceded responsibility for bus stops to underlying cities. Some cities, prominently Los Angeles, have privatized bus shelters, ceding their control to advertising companies. The bus shelter system is optimized for private advertising profit, hence leaving large numbers of bus riders - Metro's core low-come ridership, in particular - sweltering in the L.A. sun.

10. Proposer BYD has an uneven record

The main proponent of the monorail proposal is the company BYD. The company is currently manufacturing electric buses for Metro, and they may well make a great monorail... but, based on past performance (and the current proposal), it could be a stretch.

BYD has sometimes over-promised and under-delivered - including in Los Angeles and Albuquerque.