Little more than six months ago, the city of Monrovia broke ground on what is now Satoru Tsuneishi Park. The finished park is both relaxing and stirring, through the presence of the history it’s preserving.

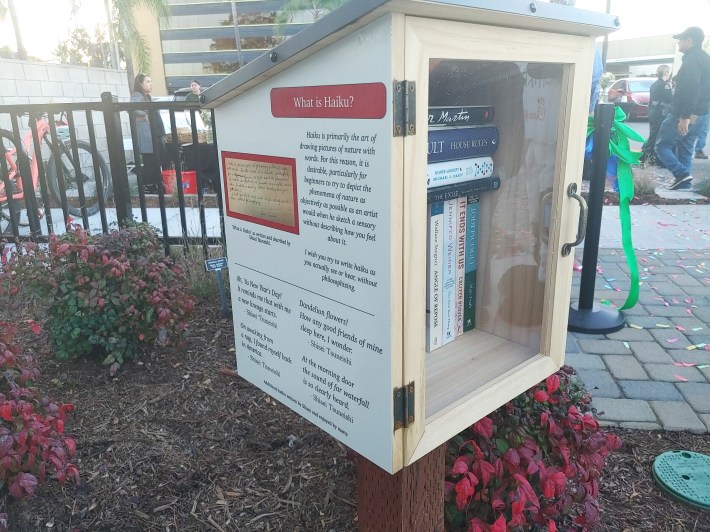

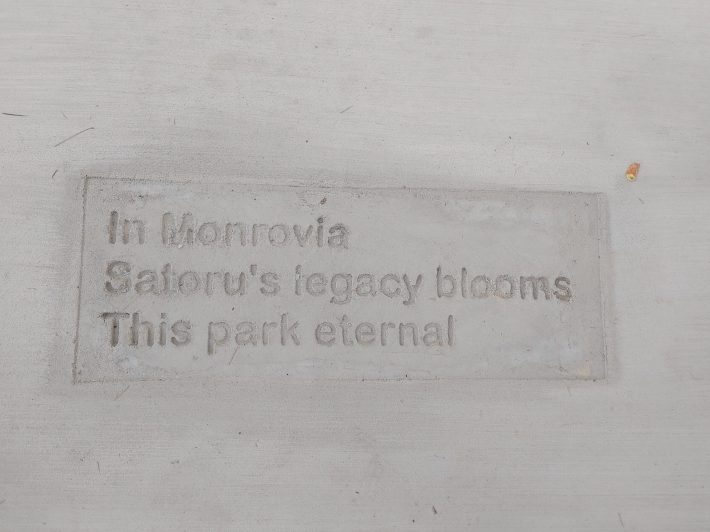

Tsuneishi Park immediately grabs your attention with a playground that looks like a beamwork house in a lilypond, and gives you somewhere to think with winding walking paths that carry you past bold murals and haikus on granite.

Last June, SBLA shared the story of Tsuneishi as told primarily by his grandson Jonathan. At Tuesday’s dedication ceremony, Jonathan’s brother Mark fleshed out his biography a bit more.

Satoru Tsuneishi (b. 1888) came to the U.S. in 1907 as a young man of 19, and he worked on strawberry farms near Chavez Ravine for 13 cents an hour. These were tough years, marked by financial hardship, racial discrimination, and limited job opportunities.

Eventually, in 1910, he was admitted to Monrovia High School. He completed his coursework in just three years, becoming the first Asian American to graduate from the school.

He married Sho Murakami, and the two started a family in 1915 as Tsuneishi attended college and began publishing haiku poetry journals. They made a living with their strawberry stand on Route 66.

Decades later, in 1942, the couple were detained by the federal government at Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming under Executive Order 9066. The order remanded all Japanese and Japanese-American civilians to various concentration camps across the country, amid a climate of racist hysteria during World War II.

Mark gestured towards the mural depicting his grandmother behind him.

“That picture was a National Archives photo of Sho in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center dining hall, and she's holding an American flag with four stars, showing her four sons who served in the US Army while they were being interned,” Tsuneishi said, all of whom are honored with banners on the park’s lampposts.

The Tsuneishis briefly returned to Monrovia after the war. Satoru’s then grown children were spreading out and making their own homes in California, leaving their patriarch to spend the next forty or so years of his life teaching poetry and traveling for his art, which was honored by the Japanese government. He died in 1987.

His interest in the nature poetry of haiku seems somewhat fated, or at least shaped, by his name. At the event’s invocation, family friend Pastor Gary Shiohama said Satoru Tsuneishi translates to something in English like a "wise everlasting rock." His pen name was Shisei, meaning "posture" or "attitude." He took this as a first name, in place of Satoru (meaning "wise" or "understanding").

Shiohama shared a poem Shisei wrote at 30 years old.

I am a sketch divinely started

now here a dot, now there a line

to me it seems awkwardly charted

but I trust he has a sure design

O Gracious Hand guide every stroke

my brush falls short my hand is weak

my latent powers their god invoke

and I thy inspiration seek

I hope that some day I shall be

a finished work of God

O soul even though it takes eternity

what matters that? Pursue thy goal

- Shisei Tsuneishi, 1918

Twelve of his poems are rendered on different surfaces around the park.

Additionally, the Tsuneishi family supplied historical photos of Monrovia’s pre-war Japanese community that are displayed in a triptych on the park’s Bigbelly trash cans.

The event was quite joyous overall. A traditional Seishun Taiko youth drum group opened the program and the Tsuneishi family expressed their heartfelt thanks to the city before Satoru’s last living son, Yoshi, cut the ribbon to open the park.

But City Manager Dylan Feik also struck a tone of remorse and humility in his remarks. He shared that in 1942 and 1943, Monrovia’s city council had adopted Resolutions 1638 and 1693. One had called for the removal of all Japanese people from the West Coast for the duration of WWII. The other opposed their return.

Although President Reagan made a formal apology and reparations to Japanese Americans in 1988, Feik lamented that Monrovia did not make amends then as well.

“Somehow, the city of Monrovia never considered our own unjust resolutions until recently,” Feik said. “In one of their final acts in 2025, prior to today's celebration, the Monrovia city council, standing behind me, adopted Resolution Number 2025-70, which formally repealed Resolution 1638 and 1693.”

“The story of the Tsuneishi family is a story for all Monrovians,” Feik continued. “On behalf of the Monrovia City Council and the city of Monrovia, we offer our sincerest apology to the Tsuneishi family and to others –”

Feik paused, and a lone voice shouted “Never again!” from the crowd. Small claps began, seeming to wait for Feik to finish.

“-- including Asano, Kuramya, Ueda, Kawaguchi, Mimaki, Morimoto, and many, many others who were forced to leave this great town,” and applause broke out in earnest.

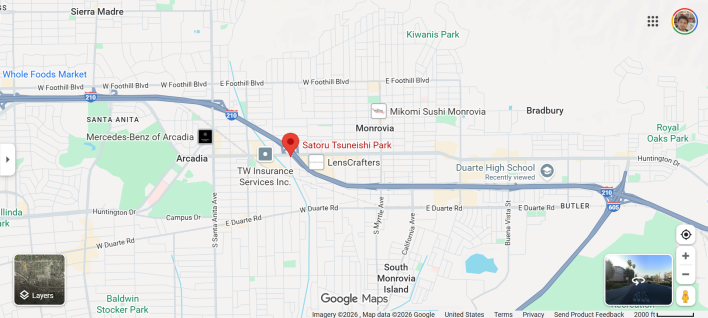

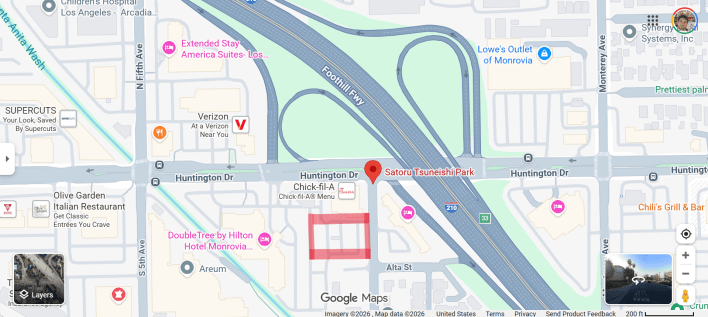

Satoru Tsuneishi Park

1111 Encino Avenue

Monrovia, CA 91016

The park is walkable from Foothill Transit lines 187 and 287, and the Metro A Line.

Streetsblog’s San Gabriel Valley coverage is supported by Foothill Transit, offering car-free travel throughout the San Gabriel Valley with connections to the A Line Stations across the Foothills and Commuter Express lines traveling into the heart of downtown L.A. To plan your trip, visit Foothill Transit. “Foothill Transit. Going Good Places.”Sign-up for our SGV Connect Newsletter, coming to your inbox on Fridays!