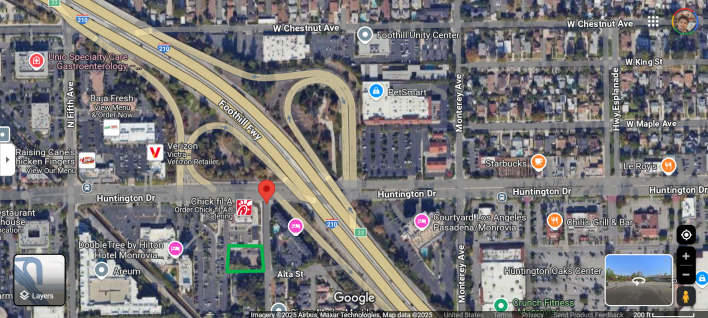

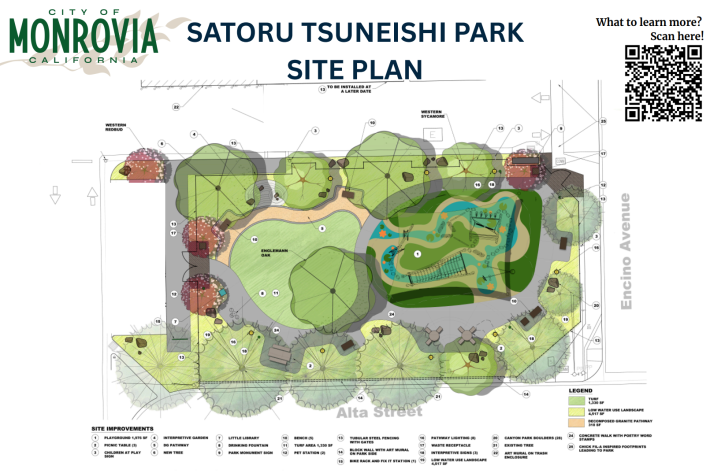

Construction has begun on a new park nestled in Monrovia’s commercial corridor, where Huntington Drive meets the 210 Freeway. The project is funded with $1.6 million from the city’s Measure K sales tax revenues, and is expected to be completed by year’s end.

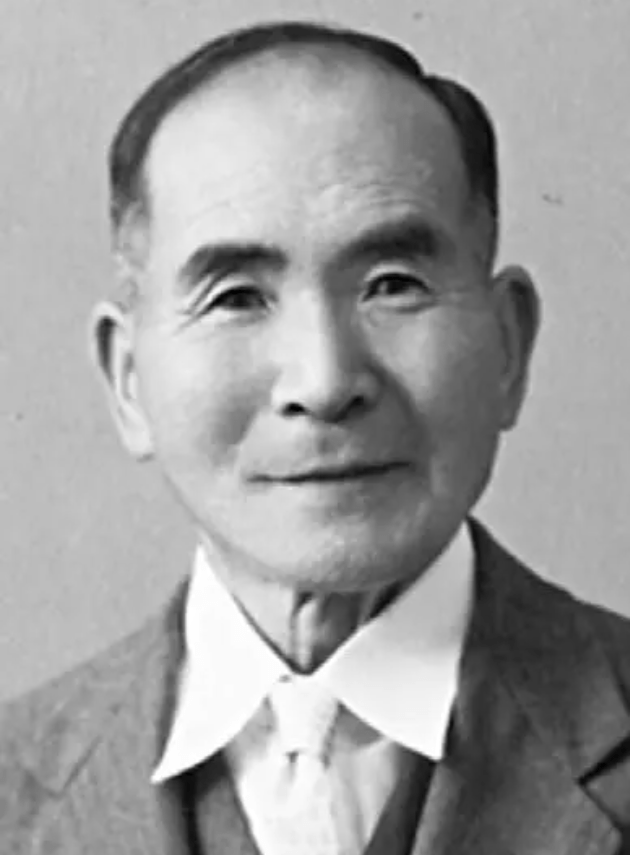

The 8600 square-foot Satoru Tsuneishi Park is named for the local haiku poet who was imprisoned in Wyoming’s infamous Heart Mountain Relocation Center during the Japanese-American incarceration of World War II. Satoru and his family would return after the war to live out their lives in Monrovia and nearby San Gabriel Valley towns.

“With this park, we're going to use every blank surface as a canvas to tell a Monrovia story,” city councilmember Sergio Jimenez tells SBLA. “We're going to be having poems stamped on the sidewalk. We're gonna have murals on the walls. We're even gonna have images on our Big Belly trash cans, so people will be able to read and see the rich diversity that Monrovia has.”

Tsuneishi Park (1111 Encino Avenue) will likely experience a lot of family foot traffic, as it’s right next to a recently built Chick-fil-A. The empty lot for the park was donated to the city in 2021 by the Hale Corporation, a local developer.

At the groundbreaking ceremony, Tsuneishi’s grandson Jonathan, who worked in the TV and film industry, gave an affectionate tribute to his grandfather and hometown.

“I'm proud that my grandfather's roots were in a community as diverse as the city of Monrovia. There's a sense of community here that one feels walking on the streets of Old Town,” Tsuneishi said.

Tsuneishi told the crowd that his grandfather came to California by himself as a teen in 1907. He came from the town of Kochi on Japan’s Shikoku island, “a region noted for castles, temples, beaches, farmers, markets and botanical garden.”

Jonathan doesn’t have a definitive answer for why Satoru left Kochi, though he notes fishing was the main line of work there. “And so the only thing I could surmise is that he wanted to start a new life. He wanted to find a way in which he could pursue his creative interest,” he told SBLA.

The elder Tsuneishi initially found work as a domestic, and his employers encouraged him to enroll in local schools.

“He went to Monrovia High and graduated along with Julian Fisher,” Jonathan says, as “among the first persons of color to attend and graduate from Monrovia High.”

While Satoru did not finish college, his grandson says it was at USC that his interest in poetry flourished. In the 1920s, he published a haiku magazine, and was later in life honored for his promotion of haiku by the Japanese government, with the Order of the Rising Sun, Sixth Class.

Jonathan shares these selections of his grandfather’s work, written under the pen name Shisei Tsuneishi.

Water’s all over

Along the weed covered path

A hazy spring night

Issei Poetry Project

Ah, ‘tis New Year’s Day!

It reminds me that with me

A new lineage starts.

from “Dust of Chysanthemums”

Wife with a child weeps

at Immigration office.

A December day --

Anthology of Translated Haiku, undated

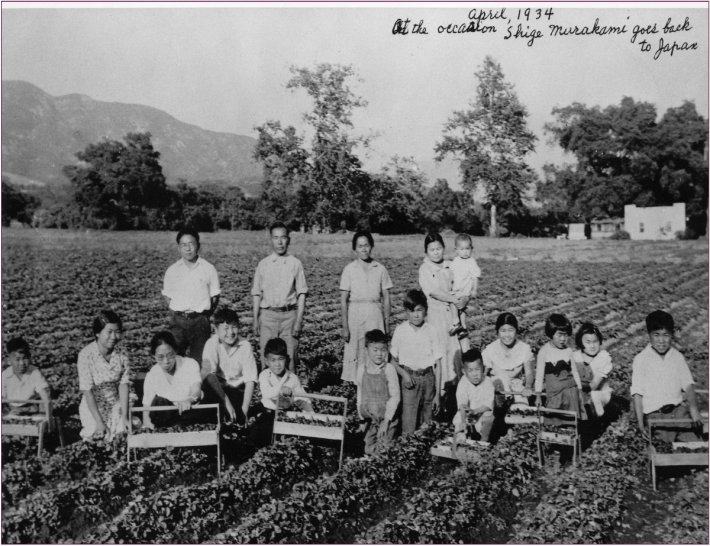

However, Satoru Tsuneishi’s primary occupation was as a strawberry farmer and father of ten. He was then part of a community of Japanese families farming in the San Gabriel Valley, until February 1942, when President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 removed them from their homes to be held for the duration of the war in remote detention centers.

“The Tsuneishi family was sent to the Heart Mountain Wyoming internment camp all while four of their sons were serving in the US military. How sad is that?” asked Mayor Becky Shevlin.

Was there bitterness for Satoru Tsuneishi and his descendants?

Jonathan struggled to quantify how his grandfather may have felt.

“While his beginnings here in the United States were very difficult – it wasn't just the internment experience, it was getting his life started, and doing it as a teenager in Monrovia back then was not the easiest thing to do – ” Jonathan told SBLA, what he did hear about Satoru's outlook was that, “You got how great life was and that he had a large family, you know."

After being released from Heart Mountain, the Tsuneishi family returned to Monrovia.

“They must have liked it a lot, because as they became successful, they stayed. They did not move,” Tsuneishi remarked to SBLA. “You know, if you think about the Japanese American community, you have some that moved to West L.A., you have some that moved to Gardena, Torrance… Our family stayed here in the San Gabriel Valley.”

And to have their patriarch honored in the SGV?

“I think our entire family is very proud of the fact that my grandfather will be remembered in this way.”

Streetsblog’s San Gabriel Valley coverage is supported by Foothill Transit, offering car-free travel throughout the San Gabriel Valley with connections to the A Line Stations across the Foothills and Commuter Express lines traveling into the heart of downtown L.A. To plan your trip, visit Foothill Transit. “Foothill Transit. Going Good Places.”Sign-up for our SGV Connect Newsletter, coming to your inbox on Fridays!