Perched on the edge of a bench on the busy third floor of the downtown courthouse on a warm October morning, 48-year-old Shamond Bennett, better known to many as Lil AD, shakes his head in disbelief at how the Police Protective League's IG post reframed LAPD's aggressive response to a peaceful candlelight vigil at Crenshaw and Hyde Park on the night of July 7.

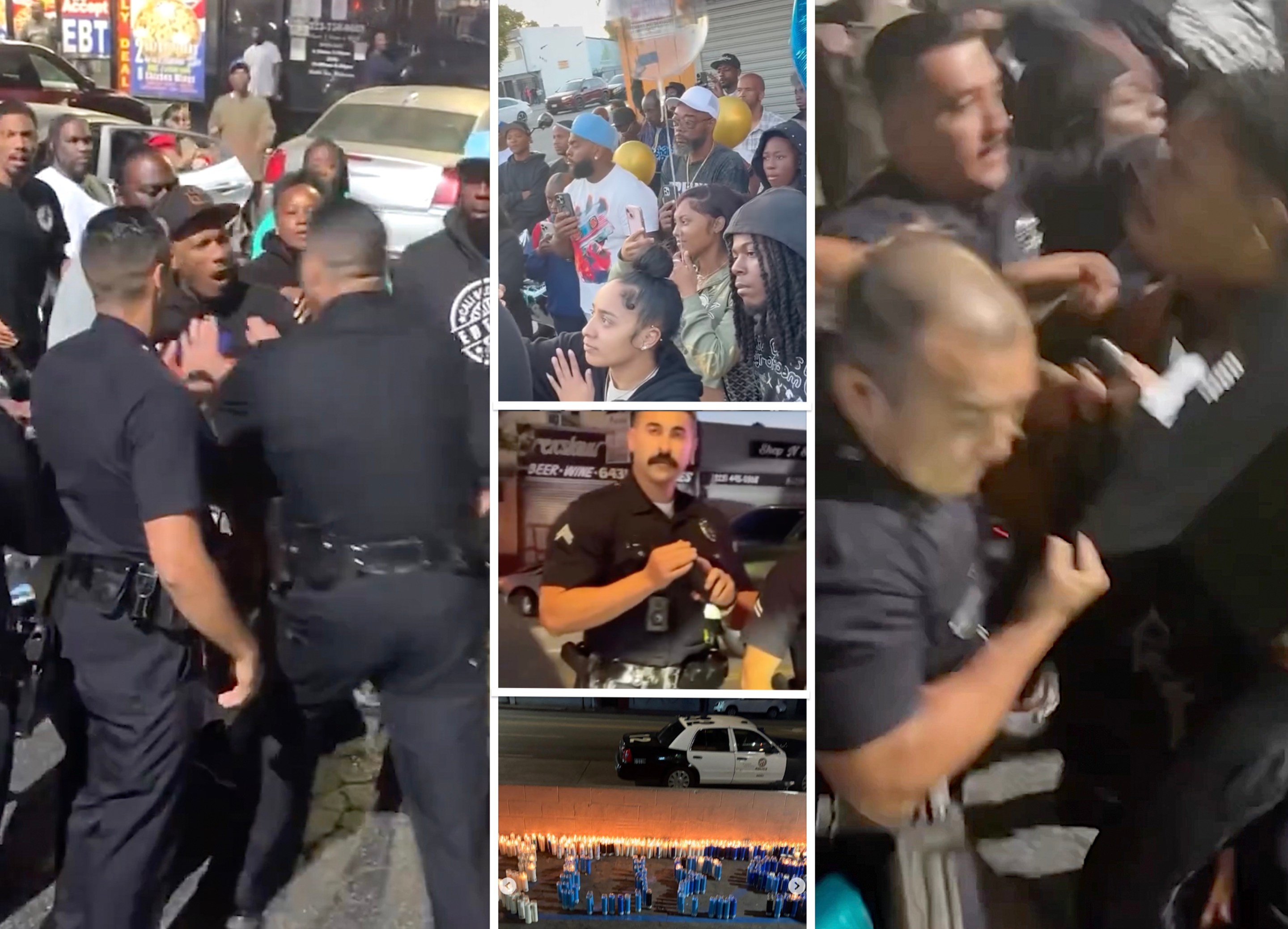

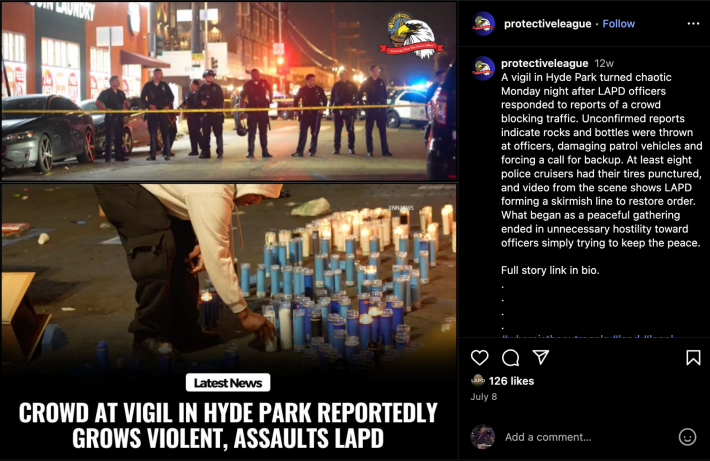

The image the League used was pulled from KTLA's wildly inaccurate report, which depicted the crowd of mourners as having suddenly launched a ferocious attack on LAPD. But the League had also put their own special spin on events in the caption, portraying themselves as hapless victims of a community that violently rejected law and order (below).

“'What began as a peaceful gathering ended in… unnecessary hostility toward officers simply trying to keep the peace'…??” Bennett reads aloud, incredulous.

He hands back my phone with a wry smile. "That’s a lie.”

Bennett would know.

LAPD's decision to assault him instead of engaging him was what had kicked off the so-called "chaos" that night.

The dismissive shove from Officer Evan Mott – forceful enough that Bennett might have been knocked off his feet if other mourners hadn’t steadied him – was captured on bystander video and posted to the Citizen app.

So was the powerful blow another officer delivered to 29-year-old Dontreal Washington’s head after he protested Mott’s treatment of Bennett.

The scenes quickly went viral, sparking outrage in the community, demands for answers, and calls for Washington and Bennett – both of whom had been arrested after being assaulted – to be released free of charge.

But despite both men requiring medical attention and being taken to the hospital that night, LAPD has yet to respond to Streetsblog's questions about the incident or publicly acknowledge the assaults via the release of a critical incident video.

Instead, both men were back in court that October morning to fight the bogus charges they’d been slapped with: Bennett with a resisting an officer and a felony strike/gang enhancement (a practice reinstated by hardliner D.A. Nathan Hochman) and Washington with resisting an officer and battery on a police officer.

It was punitive scapegoating to cover for LAPD's own mess.

But the consequences for the men were disruptive and profound. $30,000 bail for Bennett (thanks to the gang enhancement). An ankle bracelet, weekly check-ins, and the humiliation of being branded a violent flight risk for Washington. Multiple days wasted – and wages lost – in court as the case dragged on. And, if convicted, a felony record, mandatory time, and, in Washington's case, a fine as high as $10,000.

[Update 2/24/2026: At the preliminary hearing on 2/23/2026, the DA added yet another charge against Bennett: Felony battery against emergency personnel. The penalty is up to three years in jail and up to $10,000 in fines.]

__________

"A different type of hurt"

Dontreal Washington’s mother, Rayshana – the youngest daughter of famed Crip founder Raymond Washington – is still trying to wrap her head around everything that happened that night.

She says they hadn’t known Kenny "Quest" Hall – the beloved Community Intervention Specialist on the Metro Crenshaw Line and motorcycle enthusiast who died in a crash at Hyde Park and Crenshaw on July 6 – so they hadn’t initially planned on attending the July 7 vigil.

They’d already had a packed day: her son had had a job interview, Rayshana had just gotten off work, and the two were on their way to price appliances for the new apartment they’d just moved into. But after spotting family members among the growing crowd on Crenshaw, they decided to stop and pay their respects.

It was a genuinely peaceful moment in community, Rayshana says.

Fifty or sixty of Hall's friends and family transformed the humble strip mall into a sacred space. They shared memories of Hall, arranged candles spelling out "Quest," released balloons, and encouraged each other to honor his legacy by moving forward in love and faith.

Rayshana says she noticed the LAPD helicopter hovering overhead at some point. But it wasn’t until mourners began reclaiming more space for their grief – spilling out onto the sidewalks and blocking the intersection – that she saw officers approach.

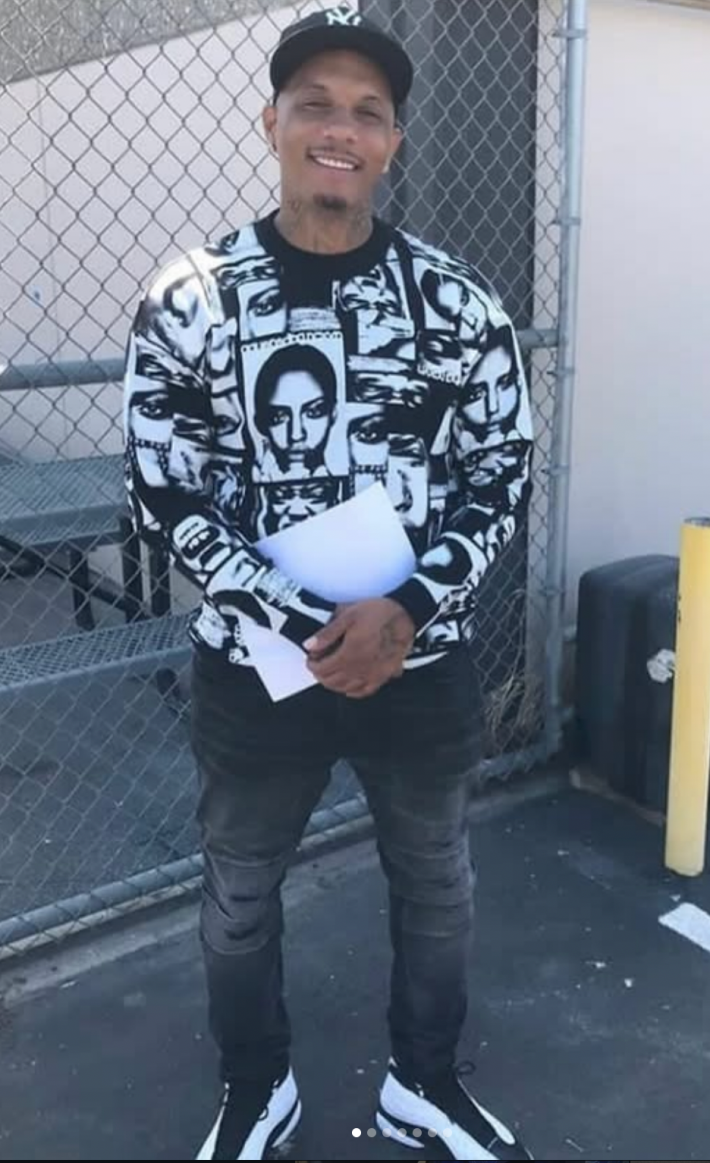

Bennett, who was there to grieve the devastating loss of a friend and to be in service as a peacekeeper, immediately recognized the fragility of the moment.

He had risen to national prominence in 2019, when he and LaTanya Ward brought rival gangs together for historic peace talks after Nipsey Hussle’s death. Since then, he'd worked to carry Hussle's legacy forward, using the respect he commands as someone who came up in the Rollin 60s to broker a better future for South Central youth.

Engaging with law enforcement – including frontlining between them and community members – is part of that work.

So he touched base with officers who knew him and let them know he was helping move the mourners to another location. He says the officers encouraged him to do his thing.

But more backup kept arriving.

According to witnesses, those officers quickly converged on the strip mall – some with their batons already out – rushing to surround mourners while also aggressively ordering them to “Get the f*ck out!”

The Washingtons, who had already jumped in their car to leave, were among those trapped in the lot. That didn’t stop officers from screaming conflicting commands that left them confused and fearful of what could happen if they were seen as noncompliant, says Rayshana.

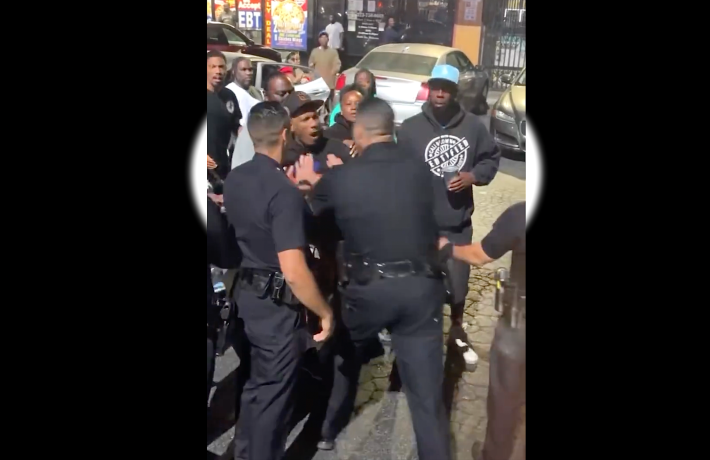

The officers also rebuffed Bennett's attempts to get them to back off and de-escalate, shoving him aside more than once.

Then came that final forceful shove from Officer Mott (below).

It was a deliberate provocation. While other officers surged forward, seemingly having been given license to now get physical with people, Mott immediately stepped back, as if to bask in the outrage he'd generated.

Bennett refused to take the bait. He immediately turned to the mourners, arms outstretched, to move them out of reach and out of danger.

The crowd also remained restrained, mostly hanging back near the entrances of the strip mall buildings. Those that stepped up to voice their outrage on Bennett's behalf (including Rayshana, in green) were not physically violent.

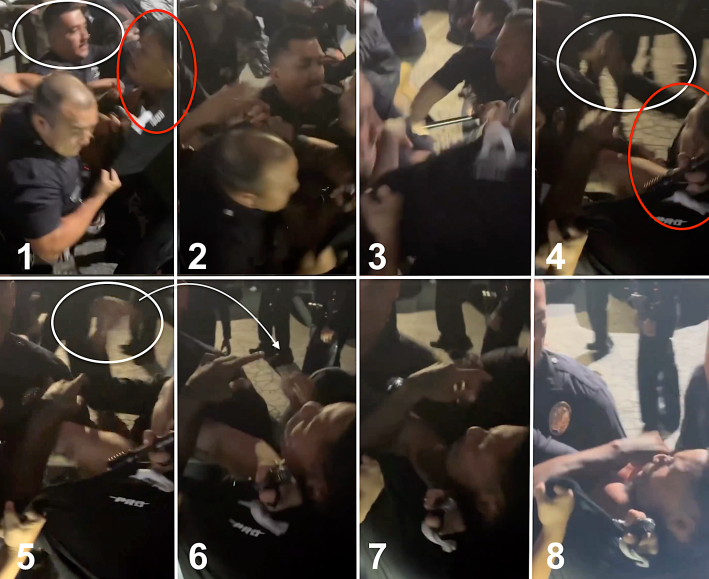

Dontreal Washington (in the black t-shirt) wasn't physically violent either. But he was upset. And when officers saw him push past his mother to angrily reproach Mott, they grabbed at his face, neck, and shirt and quickly dragged him away from the crowd.

As Rayshana screamed in horror, one pressed an arm and baton up against Washington's neck and another punched him in the head. The roundhouse blow appeared to knock him out.

Rayshana’s last glimpse of her son before being grabbed and hustled across the street was of him still lying unconscious on the ground.

She'd also seen Bennett assaulted and taken forcefully to the pavement. "They beat AD so bad," she says. Officers put “so many knees in his back" and appeared to hog-tie him, she recounts.

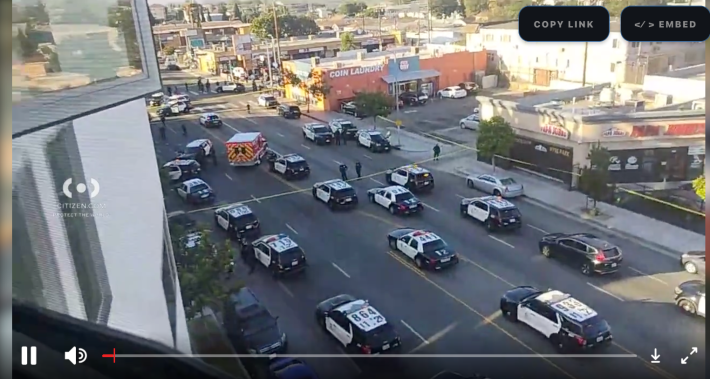

Then the cavalry arrived. Over three dozen patrol cars. Officers donning riot gear. The formation of multiple scrimmage lines. Officers crawling inside her car to search for god knows what. Officers coldly telling her that her son's heart condition was not their problem.

The department’s hostility toward the community was not news to Rayshana, but having her son beaten in front of her was. It had shaken her to her core and left her traumatized.

“As a mother of two Black males, to actually see it and it be your child..." she shudders. "It’s a different type of hurt.”

__________

"What they won’t say is, ‘OK, we were wrong.’”

Had it happened elsewhere, the LAPD’s assault on a peaceful vigil and violent arrest of two prominent community figures might have been the lede on the 10 o'clock news that night.

But LAPD got the mic. And according to them, no one was injured and no arrests were made.

So instead of asking why a few dozen peaceful mourners in a historically Black community were confronted with a show of force rivaling the Border Patrol’s militarized invasion of MacArthur Park earlier that day, local TV outlets repeated LAPD’s claims that officers were “attacked” while "responding to a street takeover."

In that version of events, the “hostile” and “unruly crowd” “quickly turned violent” and “turned on” officers trying to disperse the crowd, “throwing bottles at patrol cars and slashing tires on several of those units” and possibly even "launching fireworks at them."

The hurtful narrative compounded the harm inflicted at the vigil, the men's family members explained to community press the next afternoon. But their demands for the record to be set straight, for the men to be released, and for a meeting with the mayor did not reach the mainstream.

Some patrol car tires were indeed slashed, acknowledges Skipp Townsend, the prominent interventionist and executive director of 2nd Call.

Although Townsend hadn’t been on the scene that night, he knew the family of the culprit, he says. The young man was upset by LAPD’s disrespectful treatment of the mourners and of Bennett. But he also knew he couldn’t fight the police, so he found another outlet.

“He thought he was helping,” Townsend says with a bemused chuckle.

Townsend also says he explained all that to Assistant Chief Dominic Choi, Deputy Chief Ruby Flores, and Commander Ryan Whiteman just a few days after the incident. He was trying to lay the foundation for a broader dialogue on LAPD’s unnecessary show of force and the tensions it had generated.

LAPD claimed they'd been blindsided by the vigil – no one had reached out to give them warning people would be gathering there. Townsend's belief was that even if they hadn't gotten a heads up, the department still had a professional responsibility to treat people with dignity, have a conversation with them, and figure out what was going on instead of just leading with aggression. He’d hoped that by taking responsibility for the tire slashing and agreeing it was wrong, he would get some kind of reciprocal acknowledgment of wrongdoing from them in return.

It was not forthcoming.

“They all said the same thing, ‘Let’s build community relations,’” he says. “But what they won’t say is, ‘OK, we were wrong.’”

Agreeing LAPD "could have done things better" is not the same as admitting fault. Or stopping their officers from making false reports incriminating individuals for speaking up when they see other community members being pushed around and attacked, Townsend contends.

Meanwhile, "Shamond Bennett and Dontreal Washington still have to go to court and fight these cases” because of these false reports, he says. "It's just… it's ridiculous."

__________

"Are Y'all Deployed to Fight the Community?"

Saying they “could have done things better” also does little to address the department's conflation of Blackness with gangs and criminality.

Townsend says he remembers being struck by hearing sergeants telling their officers to learn “who’s who in the ‘zoo’” back when he first began working with LAPD. It was painful to hear his community regarded as animals, he recalls. Not only because it informed how they treated people, but also because of the harmful narratives it perpetuated to the wider public about who lived there and about the kind of policing required to control and subdue them.

Those biases remain embedded in department culture. They were even on full display during the mediation session Townsend and other community members eventually had with LAPD about their aggressive handling of the vigil.

According to a Human Relations Commission memo on that three-hour conversation, a “sergeant asserted that community takeovers for vigils are not traditional methods of honoring lives, which typically occur in churches or private homes.” He then went on to categorize “this behavior as ‘gang culture’” and to declare that “LAPD would not tolerate events that pose public safety concerns.”

Never mind that Hall was not gang affiliated. That there was no takeover. That community members had agreed to move to a new location. Or that no one had appointed LAPD the arbiter of how Black people – especially those in a historically disinvested and overpoliced community with a distinct lack of third spaces – should mourn their loved ones.

By the sergeant's own metric, LAPD had participated in "gang culture" just two weeks before the vigil for Hall by orchestrating a massive hour-plus-long takeover of streets and freeways – streamed live by Fox 11 – after Sgt. Shiou Deng was tragically killed in a traffic crash while assisting another motorist.

The "behavior" wasn't the issue, in other words. It was the people.

LAPD made that clear with an even greater show of force at that very same location just three days after the vigil, after officers Francisco Lagunas and Richard Phillips pulled up and fatally shot 63-year-old James Tullous as he fought with another community member.

This time, Townsend was at the scene immediately, both as a neighbor and to help keep things civil. LAPD “still came aggressively," even before the crowd had begun to gather, he says.

He captured some of that hostility on video (below). In it, officers can be seen unnecessarily stoking tensions and pushing peaceful onlookers farther and farther back, sometimes physically.

They even pushed around long-time photojournalist and crime scene staple Nash Baker, who angrily protested that they needed to calm down and stop putting their hands on him. [See Baker's IG livestream for more.] Then, as Baker lifted his camera to record the scene, officers actively moved to block his view. "Y'all shot him," Baker admonished. "Now let me do my job!"

As the line of baton-wielding officers continued to grow, so did Townsend's frustration. He demanded to know what this show of force was for. "Are y'all here to fight the community?" he asked. "Are y'all deployed to fight the community??"

Catching the eye of a nearby sergeant, he respectfully requested she pull back the officers posturing aggressively just behind the yellow tape. She ignored him. "This is not necessary," he insisted as she walked away. "Nobody's aggressing on you guys."

This kind of arbitrary escalation makes his own job much harder, says Townsend. It shuts down opportunities for respectful dialogue, undermines intervention workers, and ultimately communicates to community members that there is no peaceful way forward.

In the case of the Tullous shooting, for example, he had done his best to de-escalate tensions and whittle the crowd down to a dozen-plus essential people in Tullous' orbit. Among those that remained were a few who could help him keep Tullous' brother – whom he didn’t know personally – from giving into his grief and running under the yellow tape.

But that wasn't enough for LAPD. They wanted to dictate who could and couldn't observe the scene, he says. So they demanded everyone leave except Tullous' brother, Townsend, and another interventionist.

When Townsend explained he needed those folks’ help, he says officers “went and got the bean bag guns.”

He was stunned.

“[The crowd] went from fifty to twenty to sixteen. Now it's only, what, seven, eight of us, and you guys are going to get the bean bag guns?” he recalls thinking. “So that means you're getting it for us – the family and the intervention workers.”

It was now the second time in three days LAPD had sent the message that they saw the Black community – interventionists included – as a threat to police.

Then they doubled down.

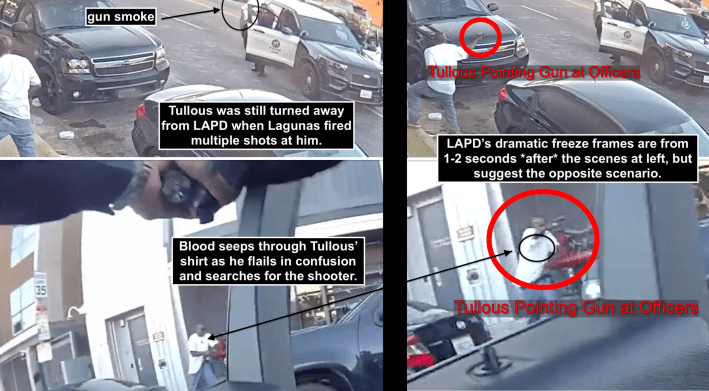

In statements to media about the shooting, they suggested Tullous, a Black man, had victimized police. Specifically, that he had taken aim at officers, potentially fired multiple shots, and effectively forced them to engage in "a return of fire."

It was all untrue. The security footage included in LAPD's own critical incident briefing shows that Tullous had tried to intimidate a man he had a personal dispute with, accidentally fired his gun as the two wrestled, still had his back to LAPD when they first pulled up and opened fire, and had been hit in the chest before he'd realized they were there. It's actually not clear if Tullous ever saw LAPD at all – they do not appear to have given him any warnings or commands before opening fire.

But once again, LAPD could not admit they were wrong.

So they strategically cropped out some of Tullous' movements as well as witnesses' reactions to the shots Lagunas fired (top left, below). Then, when Tullous stumbled forward in confusion, blood already pouring out of his chest, they paused the video for several seconds and labeled the media-friendly freeze frames “Tullous pointing gun at officers” to suggest they had not opened fire until that moment (top right, below).

___________

No time for charades

Back at the courthouse, Dontreal Washington fidgets and stretches out his legs, exposing his ankle monitor. Rayshana says she hopes the court will see reason and remove it. “My son is not violent,” she reiterates. She was tired of him being treated like he was.

The night he was arrested, officers on duty at the 77th Street Station initially wouldn’t acknowledge to a frantic Rayshana that he or Bennett were at the jail. Later that night, officers took the men – both of whom were bruised and in pain – to the hospital, where they spent the next several hours dozing upright in uncomfortable waiting room chairs. Once back in jail, the men were deemed the aggressors and denied visitors. Contact information Rayshana and Townsend had left for the men was never passed on.

Even the arraignment was an ordeal, says Rayshana. The case was held until the very end of the day, meaning the men spent all day in a holding cell. And the D.A. made wild claims about Washington in court, alleging he got out of the car swinging, hitting one officer in the jaw (the injury claim allows the D.A. to bump the charge up to a felony).

When asked about the decision to charge the men, especially in light of bystander video showing the opposite scenario to have been true, the D.A.'s Public Information Specialist Ricardo Santiago replied, “As with any case, our office filed the appropriate charges that can be proven beyond a reasonable doubt based on the available evidence.”

But three months on, LAPD was still withholding that "available evidence" from the court. The department had handed over an unorganized jumble of body cam videos from officers that had not been involved in the altercation and withheld relevant ones. Crucially, officer Mott's cam was also missing. Without those files, the preliminary hearing couldn't go forward. The day was a wash. The judge set a new date for December.*

The charade of it all grated on Bennett.

He says he had seen Mott many times before the night of July 7.

The officer had often made a point of circling the Metro stop at Crenshaw and Slauson to intimidate him and the other intervention workers stationed there. Like he was waiting for an excuse to trip them up, Bennett says.

Before his death in 2019, rapper, artist, entrepreneur, and innovator Nipsey Hussle had spoken at length about how difficult it was to get LAPD to change their mindset about the community and about those – like himself and, now, like Bennett – who had come up in gangs but were using that experience to create positive change. Especially at Crenshaw and Slauson, a cornerstone of Rollin 60s territory.

During an interview with Rap Radar in 2018, Hussle had generously said that he couldn't take LAPD's frequent harassment of him "that personal" because "the police are still getting educated to who we are and what our real intentions are.”

But all these years later, it's clear some refuse to be educated.

Bennett didn't seem to want to dwell on that. There was too much work to be done, too many kids to be saved, too many lives to get back on track. Even at the courthouse.

On the way down to the cafeteria, he'd been approached by a man who said he'd been robbed on the street. The hallways were literally crawling with cops, but the man believed Bennett was the person who could restore some order and make the youngsters see sense.

Bennett later confessed he wasn't sure how much sway he'd have in this case – it happened outside his 'hood – but told the man he'd see what he could do.

His DMs are full of requests like this, he says, shaking his head. So much so that it can be overwhelming at times. But it also speaks to the trust folks have in his leadership and dedication to making his community a safer place. It's a responsibility he didn't take lightly at Hall's vigil. And it's a responsibility he doesn't take lightly now.

"I was as hardcore as they come," he says of his history with the 60s. But now he doesn't have patience for people – police or otherwise – who are not truly committed to working for more peaceful streets. "If you're not in it for the kids, what are you doing?"

___________

*Body cam footage - access to it and the review of it - remained an issue at the December court date, according to Rayshana. The men's next court date is set for January 26.