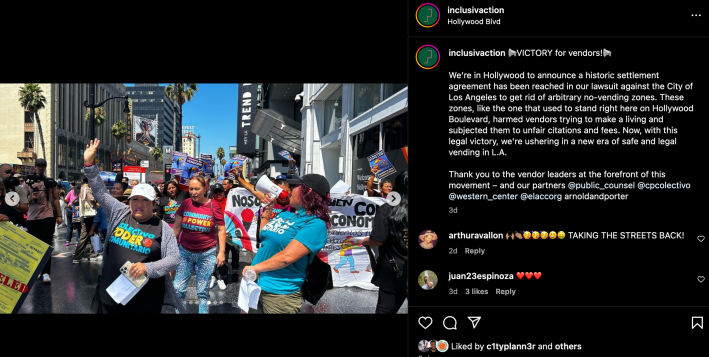

Against a backdrop of exuberant chants of "¡Cuando luchamos, ganamos!" and "¡Cuando organizamos, ganamos!" (When we fight, we win! When we organize, we win!), L.A. street vendors gathered at Hollywood and Highland last Friday celebrated a massive victory in a lawsuit they never should have had to file.

The suit, brought against the City of L.A. in December of 2022 by Hollywood street vendors Merlín Alvarado and Ruth Monroy and long-time vendor advocates Community Power Collective, Inclusive Action for the City, and the East L.A. Community Corporation, challenged the city's unlawful no-vending restrictions and sought the cancellation of tickets and fines given to vendors operating in the no-vending zones as well as reimbursements for any fines paid.

Friday's big announcement was that the plaintiffs and their legal team - Public Counsel, Western Center on Law & Poverty, and Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP - had finally emerged victorious on all fronts. The city had agreed to rescind the remaining no-vending restrictions (e.g. near swap meets, farmers’ markets, schools, and temporary events) that had not been addressed back in February, when Council voted to rescind a handful of high-profile no-vending zones.

The city also agreed to cancel all relevant citations and begin the process of identifying vendors eligible for relief and reimbursing fines paid.

On paper, it’s not hard to see why the vendors won. The city's restrictions were demonstrably out of compliance with the 2018 state sidewalk vending law, which explicitly curbs the ability of cities to limit where vendors can operate.

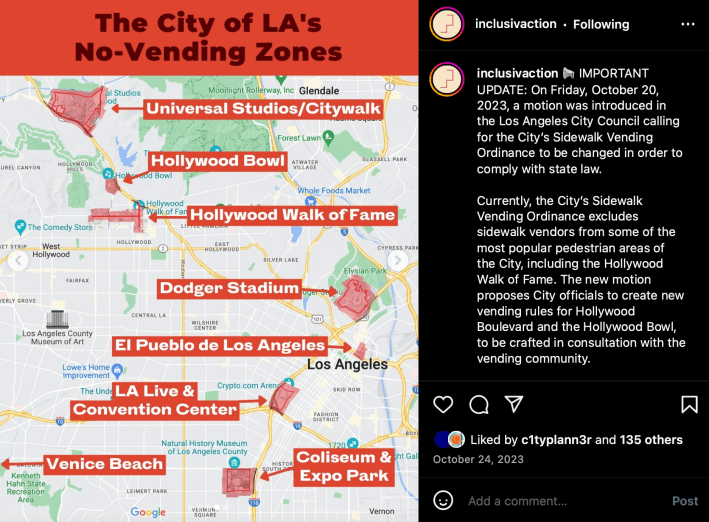

But the city was something of an expert at slow-walking efforts to legalize vending. So when passage of the 2018 bill forced it to act, current and former city councilmembers catering to business interests (or simply seeking to limit the presence of vendors in public spaces) got around the prohibition on arbitrary no-vending zones by leveraging the exception for cases where “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns” had been identified.

Although documentation supporting councilmembers' claims that vending was incompatible with large crowds was never provided, a number of no-vending zones were still written into the city's 2018 ordinance. Much to the frustration of vendors, and as detailed in their suit, those same unsubstantiated claims were then used to expand restrictions to other locations.

Street vendors paid a heavy price in the meanwhile.

They were shut out of many of the city's prime areas for foot traffic and relentlessly ticketed, hassled, and made to feel unwelcome just for being in and around areas they had lived and worked in for years. The existence of the zones also seemed to embolden passersby to be more hostile to them, further compounding their stress.

That the city would effectively force vendors to drag it kicking and screaming through the courts to address something it was aware was unlawful remains difficult to reconcile. Unsurprisingly, offers of restitution for years' worth of lost income, lost supplies, emotional harm, or other damages beyond the fines have not been forthcoming.

The toll the battle had taken on the plaintiffs was evident in their relief last Friday.

Organizer Ana Cruz, who had once been a Hollywood vendor, recalled the trauma of having Bureau of Street Services (BSS) investigators shine flashlights in her face, threaten her with arrest, and treat her like a criminal for trying to provide for her family.

Hollywood vendor Merlín Alvarado, who had received approximately 30 citations since 2018, was once physically chased by a BSS investigator for being in the no-vending zone, and had wrongly been told to stay an additional 500 feet from the 500-foot buffer zone around the Walk of Fame, said she was grateful that her co-plaintiffs had been there to buoy her spirits when her own belief in their ability to prevail had faltered.

The early days of the COVID pandemic had been particularly daunting, she said. There was very little assistance available to vendors and the city had continued to bombard them with tickets, even as business dwindled.

The mention of COVID was also a reminder of the origins of the lawsuit. Briefly, around the same time councilmember Monica Rodriguez was declaring sidewalk vendors to represent "an immense public hazard" to vulnerable people and (unsuccessfully) moving to impose an effective moratorium on vending, the city was extending a hand to brick-and-mortar businesses via the Al Fresco outdoor dining program. Intended to help brick-and-mortars better weather the pandemic, Al Fresco invited them to occupy some of the very same spaces the city had shut vendors out of.

For vendors, the double standard was nothing new. But it underscored the arbitrary nature of the city's no-vending zones, tossing “any possible justification" for them "out the window,” as press statements about the decision to sue noted at the time.

For her part, Alvarado preferred to focus her remarks on the present and the significance of what they had accomplished.

Some of L.A.’s most marginalized people had taken on the city, held its feet to the fire, and generated important structural change by getting the city to incorporate the vendors into future planning and enforcement processes around special vending zones in the Hollywood area.

The win had shown vendors that “nothing was impossible,” she said. She hoped vendors around the county could now use the platform they had built to do the same in their communities.

"¡Organízense!” she said. “¡Demanden por sus derechos!" (Organize! Demand your rights!)

Doug Smith, Senior Director of Policy and Legal Strategy at Inclusive Action for the City - one of the organizations that had been advocating with and on behalf of vendors for over a decade - also spoke to the groundbreaking nature of the victory.

The "menacing" placards warning vendors away from the Walk of Fame had been more than just signs, he said. They had told vendors they had no place there.

But "because of our lawsuit and the leadership of vendor leaders like Ruth and Merlín, we are ushering in a new era of safe and legal sidewalk vending in Los Angeles," he said. "The days of redlining vendors out of their communities are over. Policies that keep entrepreneurs and workers in the shadows harm our communities and hurt our economy, and they can and will be challenged and struck down."

In a statement sent out after the event, Alvarado and others reiterated the resilience of the vendors and what this victory means with regard to their ability to more freely participate in Los Angeles' economy. "Street vending is one of our city’s great traditions and resources," Alvarado said, "and we look forward to being fully recognized for our role as community caretakers and contributors.”

Per that same statement, once the settlement is approved by Council and the mayor next month, the City will have 90 days to gather all of the relevant citations, identify the individuals eligible for relief, and send the required notices to those vendors. Individual vendors should call the Citation Processing Center to initiate the refund process.

Public Counsel livestreamed the event. Watch it here.