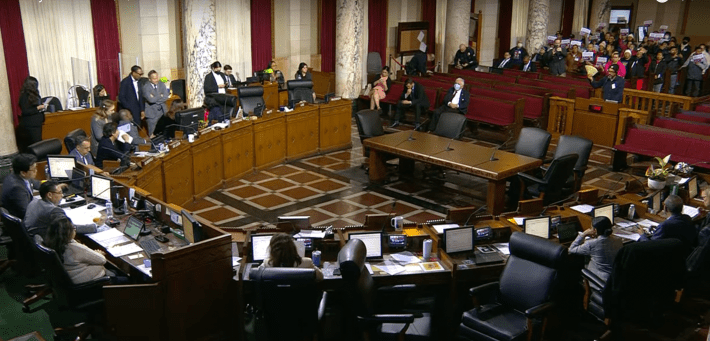

Sounding a lot like he had entered his Ja Rule era during a packed session of City Council on February 6, disgraced L.A. City Councilmember Kevin de León announced he was “perplexed, befuddled, bewildered” about why it had taken five years to rescind the no-vending restrictions councilmembers themselves had written into the city’s street vending ordinance in November of 2018.

The existence of the restrictions put L.A. at odds with S.B. 946, the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act that legalized street vending statewide.

That bill, dubbed #EloteJustice by author and then-State Senator Ricardo Lara, explicitly curbed the ability of cities to limit where vendors could operate.

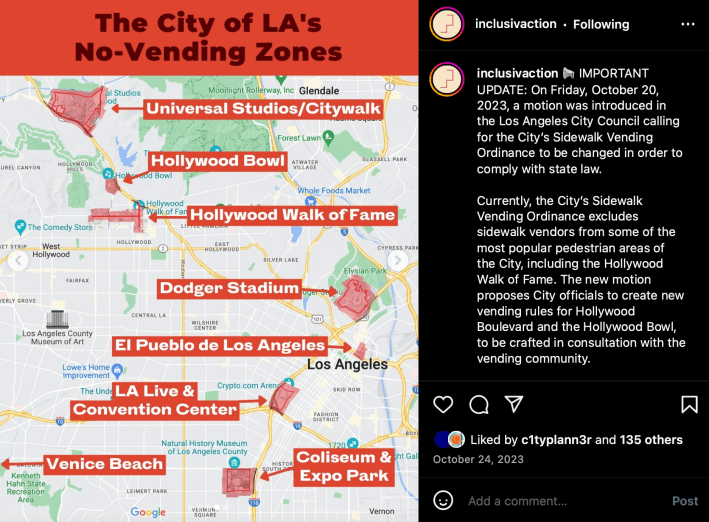

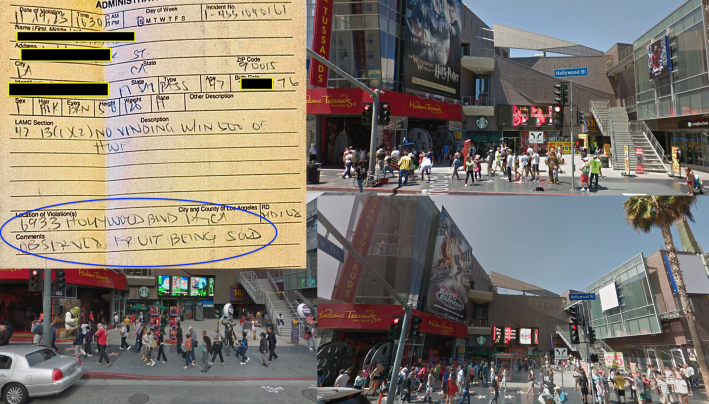

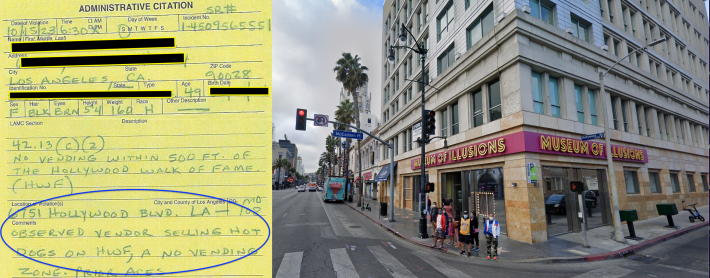

Just two months after the bill was approved by the governor, however, councilmembers improperly leveraged the allowance for restrictions in the name of “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns” to shut street vendors out of some of the city’s prime areas for foot traffic (and where a taste of Los Angeles street cuisine might be most welcome): within 500 feet of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Universal Studios/Citywalk, El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, Crypto.com Arena/LA Live, and the Hollywood Bowl, Dodger Stadium/Elysian Park, and Coliseum/Banc of California Stadium on event days.

That it had taken so long - and, ultimately, a lawsuit challenging the zones filed by street vendors and vendor advocates in December of 2022 - for Council to correct something they were aware was problematic at the time is indeed a stain on the body's record.

But de León, in what appeared to be a bid to depict himself as a champion for street vendors, seemed blithely unaware of that history.

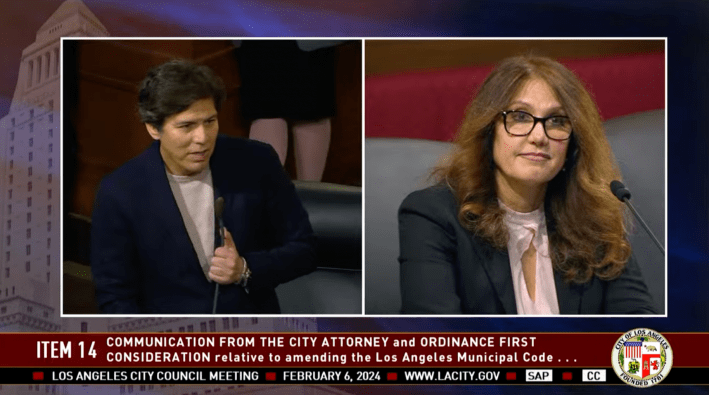

In a cringeworthy attempt at grandstanding, he asked Chief Assistant City Attorney Valerie Flores to explain the delay, despite her having provided an abridged but relatively comprehensive account of that history just moments earlier, in response to a prompt from Councilmember Hugo Soto-Martinez.

Then, dissatisfied with Flores' second recounting of events, de León condescendingly told her he preferred a "more nuanced answer" and asked that she explain the delay a third time.

His monologue – during which he namechecked himself as a co-author of the state bill (despite not being officially listed as a co-author or being present to lend it his vote either time it came before the State Senate), effectively accused everyone but himself of foot-dragging on vending issues, and managed to demonstrate just how little he knew about either the barriers vendors face or the city's legislative process – was not well received.

Flores reminded de León that the City Attorney’s office does not “spontaneously bring ordinances” for Council to approve and that they must instead wait to be directed to create and amend ordinances. In this case, when that direction came from a judge, she said, they engaged Council and then, in accordance with protocol, waited for Council's instructions regarding next steps.

Council President Paul Krekorian, who had co-authored the motion addressing the no-vending zones with Soto-Martinez, didn't hide his annoyance. Although he did not address de León directly, he pointedly declared he would never want to see a situation where the City Attorney made independent policy decisions. “That’s up to this council,” he said tersely. “The City Attorney should not make policy. Only this council should make policy.”

Notably, de León's ramblings about how "pre-emptive strikes" were more his personal leadership style do not hold up well against his own record. He'd had ample time to be responsive to the vendors in his district and lead on their behalf during his three-and-half-year tenure. Yet he had chosen to do neither.

One such opportunity for heroic gestures had presented itself just last fall, when the City Attorney requested Council hold a closed session to discuss the court's tentative findings regarding the lawfulness of the zones. That closed session was scheduled first for October 13 and then moved to the 20th. As they had many times before, vendor advocates showed up to City Hall on both those dates to plead with councilmembers to rescind the restrictions and treat vendors with the dignity they deserved.

Krekorian and Soto-Martinez produced the motion to bring the city into compliance with state law on the afternoon of the 20th. The motion also included a key ask from the vendors: that they be integrated into the planning process for special vending zones on Hollywood Boulevard and around the Hollywood Bowl.

De León had been present in council on October 20. Yet his name is not among the motion's five signatories.

De León's office did not respond to questions about his apparent lack of leadership on the zones, his broader responsiveness to vendors, or whether he had attempted to pre-empt the lawsuit filed at the end of 2022.

Perhaps his team did not wish to call attention to the role the leaked tapes exposing de León's active participation in a racist conversation at the L.A. Labor Federation played in his ability to lead on street vendor - or any, really - issues in the fall of 2022.

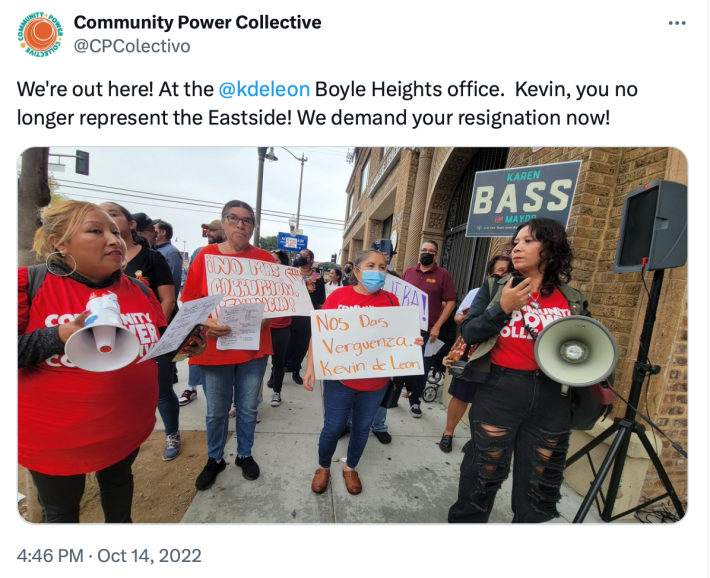

While de León laid low and avoided the press immediately following the publication of the leaked tapes on October 9, 2022, vendors and vendor advocates had been among those calling for his resignation outside his Boyle Heights office.

Like so many in the city, they were disgusted by de León's overt anti-Blackness, targeting and disparaging of a colleague's Black child, failure to defend Oaxacans, giddy backroom dealing regarding a historically Black council seat, divide-and-conquer approach to redistricting, and nakedly self-interested power scheming.

Although de León embarked on a flaccid apology tour a few weeks later, he would not make his official return to council chambers until mid-December - about a week after vendors Merlin Alvarado and Ruth Monroy and long-time vendor advocates Community Power Collective, Inclusive Action for the City, and the East L.A. Community Corporation filed their suit.

One year later, as the City was scrambling to address the vendors' claims while gearing up to face them in court, de León was busy sending out over a million pieces of mail on the city's dime, gearing up for his re-election bid and lining up campaign donors, looking pensive and contrite while attempting to rehab his image in local media, filing his own lawsuit against the individuals alleged to have leaked the Fed tapes, and dipping his toe into negative campaign messaging via push polling.

His seething lawsuit, filed two weeks before Krekorian and Soto-Martinez moved to rescind the zones, takes bitter (and demonstrably false) swings at "dying [news] outlets," "improper" interpretations of "Spanish slang," and "vitriolic" critics who he claims refuse to recognize that "Mr. de León never made any comment that was even remotely offensive during the illegally recorded conversation."

A cynically worded English-language survey about his candidacy was sent out a month later. The push poll - a negative campaigning technique designed to influence how voters perceive specific issues or candidates - asked respondents about their views on Black Lives Matter, insinuated some of his opponents sympathized with Hamas and pedophiles, described de León as a victim of "dangerous extremists from outside his district who want to cause him physical harm," and asked whether constituents thought de León should stay in office or "live in fear."

Despite being such a significant issue for so many in his district - and one he made such a point of taking credit for during his February 6 remarks - vending and his track record on vending-related issues did not merit a mention in the survey. Nor have they appeared on any of his campaign materials since.

Not one to let an opportunity to pander slip away, however, de León congratulated the vendors - and the women, in particular - on securing the repeal of the no-vending zones. It was a "gigantic step forward...for the well being of our people," he said in Spanish. "Qué vivan los ambulantes. Qué vivan."

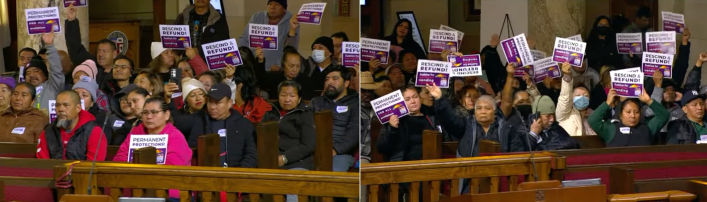

If he noticed that their signs indicated there was still more to be done - specifically, that they be reimbursed for the fines they had racked up in the zones Council had wrongly shut them out of - he gave no indication.

Unfinished business

De León’s theatrics put him in a category of his own, but it would be unfair to suggest that he alone was the reason the vendors had had to resort to a lawsuit.

Just getting an ordinance across the finish line had been its own ordeal. Council had spent years slow-walking the creation of a vending program after current councilmember Price and soon-to-be incarcerated former councilmember José Huizar introduced their motion to bring vending out of the shadows back in 2013.

Even the 2016 election and the concern that immigrants could be deported for minor infractions weren't enough to light more than a small fire under the body. Council finally decriminalized vending in early 2017, but formulation of an actual ordinance continued to stall, thanks in great part to pressure from business owners demanding a veto over where and when vendors could set up.

It took the threat of a state bill to put the ordinance back on the table. The bill had the added benefit of nuking the more draconian limits councilmembers had initially sought - e.g. only allowing two stationary vendors per block, restricting the hours vendors could be out, or requiring vendors to get permission from the adjacent brick-and-mortar businesses to be there.

Yet, in an October 2018 joint committee session dedicated to reconciling the city’s draft vending regulations with S.B. 946, former councilmember Mitch O’Farrell immediately requested no-vending zones be incorporated into the draft framework. O’Farrell had been a consistent antagonist to vendors, asking the City Attorney for help in shutting them out of Echo Park back in 2013, attempting to push them off Hollywood Blvd. by wielding the bulky items ordinance against them in the summer of 2018, and calling for restrictions on park vending, saying swarms of vendors would overrun Echo Park Lake and ruin people’s experiences in green spaces.

Price, who also favored stricter regulations, asked City Attorney staff if documentation supporting health and safety claims was necessary to carve out no-go zones. Upon learning it was, he requested findings to that effect be prepared and presented by the Chief Legislative Analyst (CLA) before the draft ordinance was finalized.

Everyone who signed off on the committees' recommendation that no-vending zones be written into the ordinance – which included current councilmembers Price, Bob Blumenfield, and Monica Rodriguez – was therefore aware that health and safety claims needed to be substantiated to be in compliance with the state law.

None of the documents subsequently produced by the CLA included any such findings or data – something Chief Assistant Attorney Flores acknowledged in her remarks this past February. Yet the claim that vending was incompatible with large crowds and forced people to walk in the streets was written into the ordinance anyways.

Much to the frustration of vendors, and as detailed in their suit, those same unsubstantiated claims were then used to expand restrictions to other locations.

The creation of the Al Fresco outdoor dining program in May of 2020 - allowing restaurants to co-opt sidewalks and parking lots for outdoor dining via a streamlined approval process - added significant insult to injury.

A pandemic-era solution crafted to mitigate losses borne by brick-and-mortar businesses, it invited restaurants to occupy some of the very spaces that vendors had been shut out from. Notably, the program was also proposed around the same time that councilmember Rodriguez (unsuccessfully) moved to impose an effective moratorium on vending, claiming vendors constituted "an immense public hazard" and a threat to other vulnerable people by attracting crowds.

The double standard was nothing new. Street vendors have long been excluded from initiatives aimed at "activating" and "re-imagining" L.A. streets (e.g. People St and Great Streets). They are not consulted or welcomed when major changes are planned for spaces they've occupied for years (e.g. the Rail-to-River walk/bike path). And even after the state law made clear vending should not be restricted, councilmembers (unsuccessfully) continued to seek new ways to chase vendors out of spaces: via the enforcement of permits that were nearly impossible to obtain [Rodriguez], siccing law enforcement on vendors who provided seating in the public right of way [CM John Lee], or simply putting up ominous and confusing signage in English and hoping it would be enough to scare vendors off [O'Farrell].

But Al Fresco proved to be the tipping point.

In a press statement about the decision to sue the city, Monica Mejia, President & CEO of ELACC, explained that the existence of the program and the way it granted more physical sidewalk space to brick-and-mortars tossed “any possible justification for these restrictions [on vending]…out the window.” It also reaffirmed the restrictions were “enacted solely” to appease local businesses and neighborhood associations, she said.

In the meanwhile, the vendors had paid a steep price.

As Merlin Alvarado, one of the plaintiffs, explained during public comment on February 6, the vendors seated behind her had each accumulated anywhere between 50 and 150 tickets for working in the no-vending zones. As detailed in the lawsuit, she could not be sure how many outstanding tickets she herself had accumulated because of how chaotic enforcement could be. She had once received two separate tickets in the mail purporting to be from the same day. On another occasion, she had been wrongly ticketed for vending within 500 feet of the no-vending zone (which already included the 500' buffer). Either way, the "exorbitant" fines were beyond anything she or her colleagues could ever hope to pay, she said.

Pointing out that the ordinance change - while welcome - would not ease the vendors' financial burden, she urged councilmembers to formally take up that matter.

Sergio Jimenez, Senior Organizer for Street Vendor Justice at Community Power Collective, put the vendors' frustration in even plainer terms. He chided Council for having to be sued into acting on vendors' behalf, for not agendizing the motion until just two weeks before the trial was supposed to go forward, and for not providing clearer assurances "that these no-vending zones won't simply be replaced with other arbitrary prohibitions on vending."

"We're also dismayed that the city has offered nothing to repair the deep harms caused by the hundreds of citations and hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines imposed on low-income immigrant families," he said. Vendors had been handed at least 45 citations after the amendment to the unlawful ordinance was proposed last October, he explained, waving a yellow fan of tickets. "This is a crime."

In a document submitted to the court detailing 107 tickets just eight vendors had received between August 2023 and January 2024, Jimenez had argued that this "crime" went beyond the financial burden the citations imposed. Per the vendors he met with, giving license to law enforcement to harass and push them out of no-vending zones had validated and heightened anti-vendor sentiment in those areas, putting them at even greater risk for hostility and violence.

That the most economically marginalized people in the city should have to expend so much time and energy lobbying to have their basic rights acknowledged and upheld remains one of this city's worst attributes.

Especially since the vendors had done their part to avoid litigation. As Doug Smith, Senior Director, Policy & Legal Strategy at Inclusive Action noted, the Hollywood vendors had actually taken the initiative to craft a "proposal for a special vending district that would balance any genuine safety issues with economic inclusion." But when they approached councilmembers in the hopes of opening a dialogue, those "proposals fell on deaf ears."

The success in getting the no-vending zones rescinded, Smith said, was "a testament to the perseverance of L.A.'s street vendors, who take time away from nourishing our communities to organize and build a movement that consistently demands and achieves justice."

Whether that is enough to inspire Council to meet all of their demands is an open question. The February 15 trial date was postponed to April 4 to allow for negotiations on the vendors' outstanding demands.

The greater goal, as noted in a joint statement from the plaintiffs and their legal representation (Public Counsel, Western Center on Law & Poverty, and Arnold & Porter) is to see L.A. "set on a better path to fully include the vending community in the local economy."

In a place where street vending is so integral to our economic, social, and cultural landscapes, there can be no other outcome.