Last week, the street vendors and advocacy groups suing the City of L.A. over its failure to bring itself into compliance with the state vending law announced that the trial - scheduled for April 4 - had been postponed yet again so the parties could continue their negotiations.

The statement released on behalf of the plaintiffs - Hollywood street vendors Merlín Alvarado and Ruth Monroy, community empowerment organizations Community Power Collective, East LA Community Corporation, and Inclusive Action for the City - and their non-profit legal team sounded somewhat optimistic.

“We are committed to ensuring that vendors are not subjected to harmful and unlawful vending restrictions and penalties. In pursuit of this goal, we have made valuable progress in settlement discussions with the City of Los Angeles. To ensure that the remaining issues identified in the lawsuit are fully addressed in a potential settlement agreement, our trial set for April 4, 2024, has been moved to May 16, 2024."

But the plaintiffs know better than anyone that getting the city to acknowledge its obligations to street vendors is no easy task. Indeed, they had launched the lawsuit in December of 2022 precisely because of how unresponsive the city has been.

Unlawful Restrictions

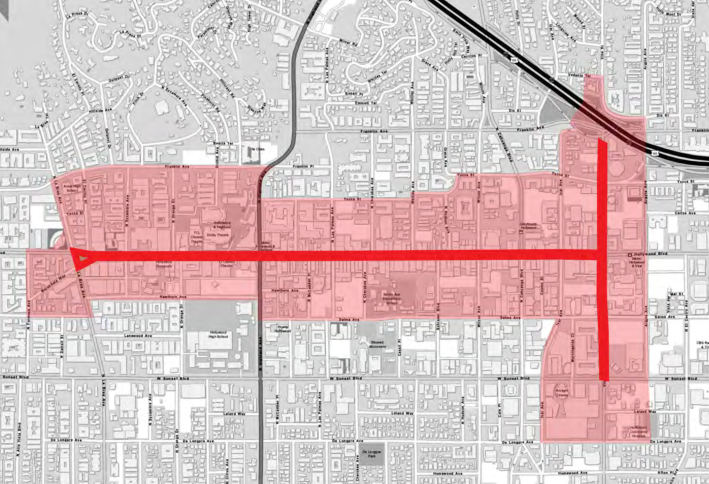

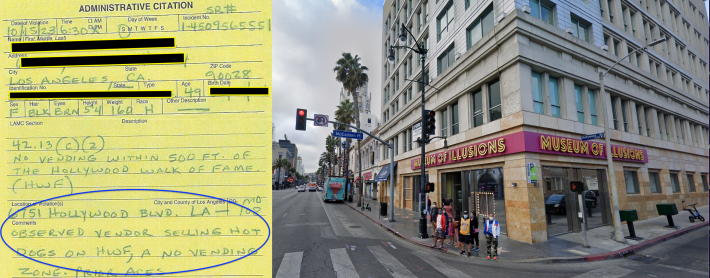

Back in 2018, when the state bill legalizing vending was making its way through the legislature and City Council was finalizing its own draft ordinance, councilmembers scrambled to insert restrictions the City Attorney warned would likely not be in compliance with the bill. [The state bill, S.B. 946, disallowed no-vending zones except in cases where “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns” had been identified; the city never provided documentation to that effect for the restrictions it imposed.] Those restrictions subsequently shut street vendors out of some of the city’s prime areas for foot traffic: within 500 feet of the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Universal Studios/Citywalk, El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, Crypto.com Arena/LA Live, and the Hollywood Bowl, Dodger Stadium/Elysian Park, and Coliseum/Banc of California Stadium on event days.

The restrictions hit vendors along Hollywood Blvd. particularly hard, banishing them not just from the boulevard between La Brea and Vine (and along several blocks of Vine), but from surrounding side streets as well. Enforcement was also particularly oppressive there. In a March 2023 statement, plaintiff Monroy - who had worked along the boulevard for several years before the restrictions were put in place - said she had been cited for her mere presence, including "as I’ve walked with my family on Hollywood Boulevard on my days off.” In the lawsuit, plaintiff Alvarado said she had once received two separate tickets in the mail purporting to be from the same day. On another occasion, she said, she had been wrongly ticketed for vending within 500 feet of the no-vending zone (which already included the 500' buffer).

Council added insult to injury in May of 2020 with the creation of the Al Fresco outdoor dining program. A pandemic-era solution crafted to mitigate losses borne by brick-and-mortar businesses, it invited restaurants to co-opt some of the very spaces that vendors had been shut out from.

Doing so effectively affirmed the health and safety justifications wielded against vendors were unfounded. And it did so via a streamlined approval process for the brick-and-mortars while permits for food vendors remained nearly impossible to obtain (thanks to the public health specifications for carts, etc. still needing to be adapted to fit the way vendors actually operated in practice).

An Unresponsive Council

Prior to filing the lawsuit, the Hollywood vendors had approached councilmembers with their own proposal for a special vending district. They had hoped to work with the city on carving out space for themselves while addressing legitimate health and safety concerns, but were rebuffed.

In a September 2023 statement, the plaintiffs expressed their dismay at the City's preference for pushing back against the vendors, first seeking for the case to be dismissed in court, then offering last-minute piecemeal compromises in council to avoid trial. This past February, one of those last-minute compromises marked a major victory for the vendors: the rescinding of the illegal no-vending zones.

But much remains to be resolved.

The suit notes the substantial costs vendors have incurred since 2018 and asks that they be reimbursed for the citations.

A document compiled by Sergio Jimenez of Community Power Collective indicated that eight vendors had received a total of 107 citations over a period of just five months at the end of 2023. When multiplied by the five years the no-vending zones had been in effect, the lost wages they and other vendors incurred after being chased out of the zones, and the stress incurred from being targeted by law enforcement and other hostile actors, it's clear why a policy amendment alone does not make up for what they have lost.

Per the plaintiffs' statement last week, they are also asking that the “overbroad and unjustified distancing requirements from swap meets, farmers markets, and schools" finally be rescinded and that they be provided "assurances that future regulations will be lawful and inclusive."

With the mayor having signed the revised vending ordinance into law, vendors should now be free to set up along Hollywood boulevard. But a recent NBC4 segment (below) suggests the area still remains hostile to vendors. Vendor Alejandra Rodriguez told NBC4 she had seen a person taking photos of her, though she wasn't sure why. It also appears harassing citations are still being given out, although they are now for things like being too close to the red curb or other vendors.

The plaintiffs' April 3 statement reiterates their commitment to going forward with a trial if a satisfactory resolution that is both compliant with state law and "make[s] vendors whole" cannot be negotiated.

Either way, the statement reads, "We are confident that this lawsuit will result in the restoration of vendor rights in the City of Los Angeles and will serve as a signal to other jurisdictions that they cannot arbitrarily exclude vendors from their local economy.”