**Content warning: this post contains graphic images of the moment Earl Roots is punched

When reached by phone, 61-year-old Earl Roots said he was dismayed but not surprised to hear that, on October 31, the Police Commission had ruled the punch LAPD Officer Brian Kolke delivered during Roots' arrest on a narcotics warrant – a blow to the chest that collapsed Roots’ lung and put him in the hospital for a total of three weeks – "in policy."

The justification proved more difficult to swallow.

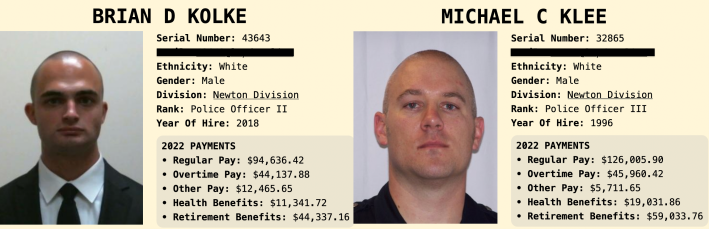

The "in policy" finding meant the Commission bought Kolke's claim that he had punched Roots to prevent the scrawny chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) sufferer he was sitting on from throwing Kolke off his back, gaining control of the handcuffs already clicked around one of his wrists, and battering both Kolke and bulky veteran officer Michael Klee to a pulp with them.

Roots, who weighs 140 pounds soaking wet, was aghast. “I'm a little bitty guy!” he exclaimed.

It was true he had initially taken a few unconvincing steps away from Kolke and Klee when they pulled up on him in front of an encampment off Central Avenue on December 19, 2022. But he only got about 20 feet before he ran out of breath and abandoned his flight, throwing up his hands and telling the officers he had asthma (below). It was also true he was not thrilled about being cuffed, Roots acknowledges. But he maintains, as he did in a September interview about the assault, that he was upset about being manhandled over a warrant he didn't know he had. He had no desire, intention, or capacity to harm the officers.

Little did he know how little any of that mattered to the department or the adjudicating bodies.

Alleged Fears of Wild Scenario Go Unchallenged

LAPD policy allows officers to use non-deadly force to effect an arrest or overcome resistance in certain circumstances. Some of the factors used to determine whether such a use was "objectively reasonable" include the seriousness of the crime or offense, the feasibility of de-escalation, the level of threat the subject posed to the officer or the community, and the officer's age, size, strength, exhaustion level, etc. relative to that of the subject.

By any of those measures, it is difficult to make the case that Kolke – a strapping, relatively youthful man – had no other option but to collapse the lung of the wheezing 60-year-old he was sitting on, who he had already managed to snap one cuff on, and whose arm(s) his even larger partner officer also had a grip on.

Yet neither the department's Use of Force Review Board (which is comprised of current LAPD officers who hear a presentation from the Force Investigation Division and then make a recommendation to the Chief) nor the Board of Police Commissioners (the civilian board appointed by the Mayor that then hears the Chief's recommendations) appear to have evaluated Kolke on his response to actual events.

Instead, they seem to have judged him on how he responded to his alleged fear of a wildly unrealistic scenario he told investigators he'd heard about in the Academy:

“I know from especially in the academy, they showed us how if you lose control of your handcuffs you can be seriously injured. And they showed us pictures of an officer that had done that - that had lost control of their handcuffs and been seriously injured by the handcuff. I used my clenched left fist and I struck [Earl Roots] in the ribs because I wanted to overcome his active resistance and stop him from possibly gaining control of my handcuffs or my hands, throwing me off balance which could hurt my partner and I. So that’s when I determined that I should punch or strike [Roots] in his rib area to overcome his resistance and to prevent my partner and I from being harmed.”

Officer Brian Kolke

The astonishing passage, included in Chief Michael Moore’s report to the Police Commission, is meant to help explain how the UOFRB determined Kolke's sucker punch to be “objectively reasonable, proportional, and necessary” to subdue Roots - a finding the Police Commission ultimately agreed with.

Instead, it raises a number of questions about the adjudication process.

Key among them is why Kolke’s claim that he believed Roots' would or could suddenly violently overpower them was not given greater scrutiny. Or any, really.

It is not unusual for officer fear to be given disproportionate weight during the adjudication process, even when those claims are demonstrably disconnected from reality (as in the Jermaine Petit case) or outright ridiculous (as in the Travis Elster case). This case appears no different in that regard. Outside of the hypothethical Kolke referenced, there is nothing in the excerpts or summaries of his or Klee's statements that suggests Kolke truly believed Roots to be a threat. [See the Chief's report and Police Commission's abridged findings for those excerpts and summaries.]

Despite claiming he was concerned about Roots grabbing at his hands, for example, Kolke did not voice his alleged fears to Klee. Nor did he ask Klee - who had a grip on Roots' left arm during the 30 seconds the two spent wrangling Roots on the ground and who told investigators he did not see Roots' protests as rising to the level of active resistance - for assistance in completing the detention.

Even the nightmare scenario Kolke cites falls apart when unpacked. A search for beating incidents involving handcuffs turns up page after page after page of stories about officers assaulting handcuffed subjects. But stories of partially handcuffed elders managing to turn the tables on a beefy pair of cops? Not so much.

More broadly speaking, and as both the investigators and adjudicators would have been well aware, the majority of nonfatal injuries officers experience are strains and sprains, generally in the lower extremities, more likely to be inflicted by subjects’ hands and feet, and more likely to be incurred when officers are alone, which Kolke was not. While detentions can indeed turn volatile, the available data also suggests it is unusual for officers to be beaten with their own handcuffs. More likely scenarios include a subject ripping their arm free to try to escape, defend themselves, use their fists, or possibly grab at a weapon or, infrequently, front-cuffed subjects using their hand positioning to their advantage.

Given the timing of Kolke's stint in the Academy, it is possible he is referencing the 2019 assault of Gainsville PD Officer Stephen Lucius by 37-year-old Eric Pitt.

Briefly, while working alone, Lucius had attempted to detain the trespassing suspect by suddenly grabbing first for Pitt's arm and then for his throat, setting off a struggle that quickly spun out of control. Bystander footage shows Pitt, panicked, arms outstretched and phone still in hand, in a headlock and being taken to the ground by Lucius. Body cam footage shows Lucius then tried to put Pitt in handcuffs as Pitt lay face up on the ground. During the subsequent tug-of-war over the cuffs, Lucius was struck in the head and began bleeding profusely.

It was a violent scene to be sure, but the takeaway was not that the subject should have been preemptively punched. It was that officers can create exigent circumstances when they eschew proper tactics and engage in unnecessary escalation and aggression.

It's also a scenario that has little in common with the encounter with Roots.

Roots had thrown up his hands in surrender when confronted. He was winded and, as the officers reported to investigators, already complaining about shortness of breath as they each grabbed one of his bony arms. And he was already known to the officers for having been "cooperative and non-combative" during their previous encounters. In fact, both Kolke and Klee cited their familiarity with Roots and his history of compliance as the reason they shirked undercover protocol and made the arrest themselves (as opposed to calling in a uniformed arrest team).

I've personally dealt with Mr. Roots, I think three prior times and he was never, in any of those instances, was never combative or - what's the word I'm looking for? He went - he went along with being detained the two prior times and then obviously the third time he was arrested so I didn't feel the need to…call the black and white...

Officer Michael Klee

These contradictions should have troubled investigators and the adjudicators alike. Whether Kolke was asked about them or if the adjudicating bodies even viewed them as such is unknown. Similarly, if either body was troubled by Kolke's decision to take aim at Roots' ribs after having heard him complain about his asthma, they made no effort to say so. And it remains unknown if anyone probed Kolke's decision to make force his first resort instead of his last.

The fact the punch was found to be "proportional" based on Kolke's claims about Roots' alleged "level of resistance" suggests they did not.

Reframing a Collapsed Lung as Compliance

What is known is that the Police Commission followed the UOFRB's lead and credited the punch with getting Roots to “stop resisting.”

Of course, Roots didn't just "stop resisting." Nor did he turn and lay face down on his stomach, as Kolke told investigators.

As seen in the surveillance footage, when Kolke delivers the blow, Roots jerks and goes limp, his chest heaving. Roots later reported that he was in so much pain that he was convinced his ribs were broken. The searing pain turned out to be the collapse of his lung, which ultimately required surgical repair.

In accepting the reframing of Roots’ collapsed lung as a form of compliance, the Police Commission effectively condoned the department's effort to downplay the harm done to him.

That, in turn, allowed Kolke to escape greater penalization for his failure to voluntarily report the use of force. Instead of an administrative disapproval, Kolke got a comment card in his personnel file.

It's a striking collective shrug, considering the extent to which Kolke's silence prolonged Roots' agony.

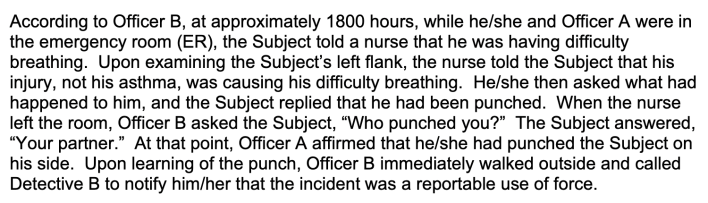

LAPD policy mandates officers promptly render aid and call for an ambulance after a use of force. Kolke did neither, instead giving Roots a dismissive kick as he stood up. When Klee, who maintains he was unaware of the punch, saw Roots struggling to breathe and made the call for an ambulance about a minute later,* Kolke stayed mum about the cause of Roots' distress. He did not report the blow to the detectives who arrived to provide backup (he told investigators he assumed Klee would do so on his behalf, but does not appear to have questioned why he wasn't subjected to LAPD's use-of-force protocol). He didn't mention it to the paramedics he rode in the ambulance with on the way to the hospital. And he opted not to report it to the hospital staff who received and treated Roots, allowing them to believe Roots' distress was due to asthma.

Roots subsequently languished, panicked, gasping for breath, and in excruciating pain, for four hours. Finally, around 6 p.m., an ER nurse determined - and Roots confirmed - his distress was due to an injury, not asthma.

Even then, Kolke wasn't exactly volunteering information. Per Klee's account in the Police Commission's report (below), he still had to ask Kolke directly to get a confirmation.

The department's reasons for papering over Kolke's silence are not difficult to discern.

At the time, they had used the confusion he created around the source of Roots' respiratory distress to their advantage. While providing his regular report to the Police Commission on January 10, 2023, Moore told commissioners that Roots had been taken to the hospital "due to a complaint of having asthma." In the critical incident briefing posted to YouTube a month later, Captain Kelly Muñiz, Commanding Officer of the Media Relations Division, also blamed Roots' hospitalization on his COPD, declaring that, "Immediately following the use of force, Roots complained of pain related to a pre-existing medical condition." Muñiz then put additional distance between the department and Roots' collapsed lung, claiming it was only discovered when he "was treated for his pre-existing medical condition."

The Police Commission's willingness to accept being misled by the Chief is more difficult to understand.

Although they quietly re-classified the punch as a "categorical" use of force in their findings (Moore had labeled it as "non-categorical" in his report, in line with the assertion that it was not the cause of Roots’ hospitalization), they did not otherwise challenge the department's messaging. Which means they also accepted the implication that Roots was at fault for not having complained about being punched in front of the same officer who punched him.

The Undercover Question

The only question that appears to have provoked debate among the adjudicators was whether Kolke and Klee were acting in a plain clothes or an undercover capacity when they recognized Roots from a distance and approached to serve him with the warrant.

Per the Chief's report, the majority of the UOFRB opined that, while the pair had briefly engaged in surveillance when they first spotted Roots at the encampment, they had been "operating in a plain clothes capacity...where their role and identity as a sworn officer was not intended to be confidential." Moore, in contrast, had agreed with the minority, which concluded the officers were engaged in mobile surveillance. As such, the minority opined, the officers should have had and adhered to a written operation plan, avoided putting themselves at a tactical disadvantage, called for uniformed officers to make the arrest, and avoided blowing their cover. The Police Commission ultimately sided with Moore, finding Kolke and Klee's violation of undercover protocol warranted an Administrative Disapproval.

The dissent within the UOFRB over what constitutes an undercover operation comes at an interesting moment for LAPD. Nearly 700 "undercover" officers are currently suing the City over the inclusion of their names, photos, and badge numbers in the larger photo roster released to journalist Ben Camacho in fulfillment of a public records request. The officers have claimed that the photo release jeopardized their safety by compromising their identities and operations. The City, in turn, is suing Camacho in a misguided bid to appease them.

As noted in an L.A. Times story unpacking the "undercover" label, the actual number of officers working deep undercover is fairly small. But the rank-and-file have clamored to have protections extended to the much broader set of officers working in other "sensitive" capacities.

In response, per the Times, Moore sent a department-wide email announcing he had ordered an audit of officers in more sensitive roles and identified a number of units and divisions whose personal information would not be released in the future. Those in plain clothes are included in that list.

The impunity with which Kolke was able to assault Roots and the limits on the department's ability to monitor the way plain clothes officers engage the public (they do not wear body cams or have visible name tags or badge numbers) would seem to suggest the public was more at risk than the officers.

It is unknown if Moore's recommendation to penalize Kolke and Klee for shirking protocol has any relation to the heightened attention on "undercover" operations. But it does seem to signal a desire to give the appearance of discipline in those gray areas. At least, on paper. Kolke and Klee's own statements to investigators imply they had previously interacted with Roots while in a plain clothes/surveillance capacity. They are likely not the only ones to conduct operations that way - earlier this year, another set of Narcotics Enforcement Detail officers working in plain clothes officers arrested 51-year-old Derrick Harden for meth possession. Though in need of medical care, Harden was not taken to the hospital for several hours; he died in the 77th St. jail the next day.

__________

For his part, Roots still can't wrap his head around everything he was put through for a warrant he maintains is LAPD's fault. He says that because the officer that had originally booked him for crack sales had not asked him to verify his address, he never got any court papers and wrongly assumed the charge had been dismissed.

He also struggles with the idea that the "in policy" ruling means the burden of holding Kolke accountable now falls on his bony shoulders. It's not that he hasn't contemplated a lawsuit. But when pressed on the subject, it is clear he finds it overwhelming. He'd been sent home from the hospital just a few days after his December arrest, when LAPD told staff they were releasing him from custody. It was too soon. Two weeks later, he woke up in the middle of the night feeling like his chest had caved in. He finally got the surgery he needed, but the whole experience has left him traumatized. He'd like to move on.

He says he's pleased to know his story is out there, however. That may have to be enough.

___________

To see Streetsblog's earlier coverage of Earl Roots' case, click here. To see the full incident video and critical incident briefing, click here. To read the Chief's report, click here. To read the Police Commission's abridged findings, click here. Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman.

*Re: the delayed call for an ambulance. At the time of Streetsblog's September story on Roots, only two things were clear: 1) there had been some delay between the punch and the call for the ambulance and 2) the ambulance did not arrive until approximately seven minutes after the punch. Klee had made a Code 4 - "no further assistance needed" - call immediately, but it was unclear when he had called for an ambulance. LAPD would not comment on when that call was made. Despite a thorough examination of the incident video and citizen-streamed scanner feeds, I was unable to pin down a specific time and speculated the delay could have been as long as five minutes. This was incorrect. I had also assumed Klee was aware Kolke had punched Roots; it was not until I received the Chief's report in October that I learned Klee told investigators he had not seen or known about the blow.

In his report to the Police Commission, Chief Moore claims a call for an ambulance was made "immediately." A close re-examination of the available footage and scanners indicates the Chief is still not being truthful. Klee - who, again, says he was unaware of the punch and therefore would have ascribed Roots' respiratory difficulty to his asthma complaint, not an injury - appears to make a radio call approximately one minute after the punch, after he and Kolke failed to drag Roots to his feet. Although the ambulance request itself is not captured on the scanner, around that time, a single word, "breathing," is heard (though it is unclear if it was a dispatcher speaking or communication tied to a completely unrelated incident) followed a few seconds later by Klee identifying himself and a dispatcher asking Roots' age. The larger point being, a call for an ambulance appears to have been made about a minute after the use of force, but it wasn't specifically to render aid related to the use of force. Had it been, Roots' inability to breathe would have been treated with much greater urgency.

Public records requests made for the radio calls, OIG report, and Force Investigation Division transcripts were effectively rebuffed. The department claims the investigation is still open and that the release of any materials before June of 2024 would substantially interfere with it.