Out of policy.

That’s how the Board of Police Commissioners (BOPC) ultimately ruled on the eight shots LAPD Officer Carlos Tovar fired at 30-year-old Travis Elster as he fled a pretextual traffic stop at Manchester and Figueroa on February 9, 2021.

The BOPC's decision, the abridged summary of their findings says, was "based on the totality of the circumstances" and the belief "that an officer with similar training and experience as [Tovar] would not reasonably believe [Elster's] actions presented an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury and that the use of deadly force would not be proportional, objectively reasonable, or necessary."

On that specific issue, at least, the BOPC would have been hard-pressed to rule any other way.

The shooting took place after Tovar and a partner officer approached 30-year-old Travis Elster about being double-parked in a narrow lot outside a strip mall fast food restaurant. Elster had recognized it was a pretextual stop and fled the scene, carefully easing his vehicle around Tovar, who had initially positioned himself in front of the SUV. After stepping out of the way of the vehicle and despite not having seen a weapon in Elster's hand, Tovar still fired off eight rounds at Elster as the SUV merged into rush hour traffic along Manchester Boulevard, just west of Figueroa. [Though badly shaken, Elster was fortunately not hit; see our previous coverage of the incident here.]

LAPD policy prohibits officers from firing at a moving vehicle.

Bullets meant for the subject could hit bystanders or injure or kill the driver, sending the vehicle out of control. Officers are thus not to fire "unless a person in the vehicle is immediately threatening the officer or another person with deadly force by means other than the vehicle." The policy also declares that the moving vehicle itself "shall not presumptively constitute a threat that justifies an officer’s use of deadly force." Thus, "an officer threatened by an oncoming vehicle shall move out of its path instead of discharging a firearm at it or any of its occupants.”

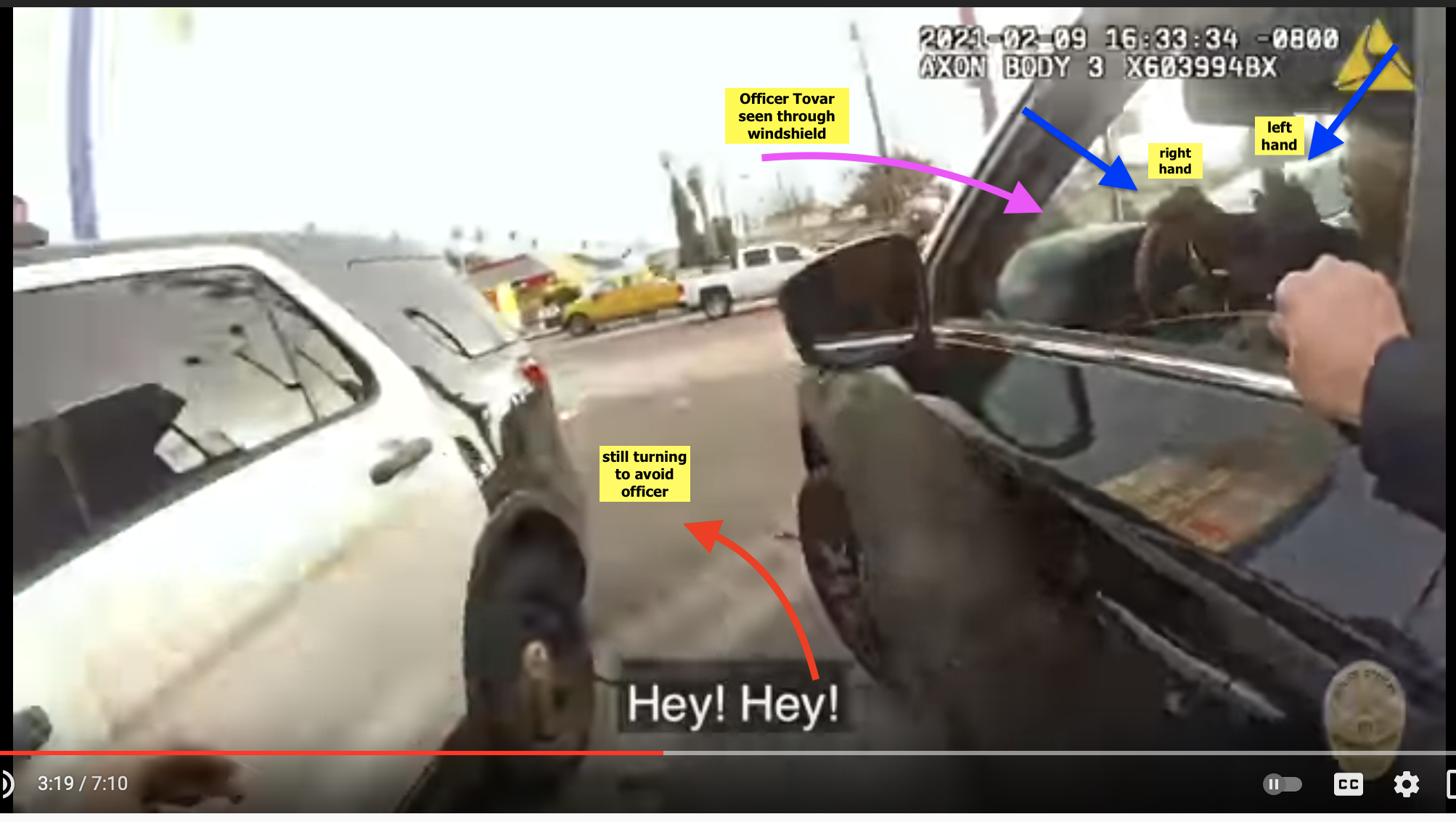

Tovar, who the Commission noted should not have positioned himself in front of the vehicle to begin with (per LAPD training), did move out of the way at the same time that Elster cranked the wheel hard to the left to avoid him. But once clear, Tovar immediately opened fire and continued to fire even after Elster was some distance away, further endangering everyone else along the boulevard.

The out-of-policy ruling was therefore not unexpected. And the finding that officers substantially deviated from training without justification in basically every other aspect of the stop, resulting in an Administrative Disapproval ruling with regard to their tactics, was welcome.

The Commission's failure to engage deeper issues with department culture and practice the stop illuminated, on the other hand, was troubling.

Even within the areas the BOPC is tasked with focusing on in use-of-force cases - officer tactics, the drawing/exhibiting/holstering of weapons, and the use of force - there was room to probe what drove officer decision-making. Instead, shaky justifications for the stop were allowed to stand. Easily falsifiable claims - both by the officers and the department itself - were given the benefit of the doubt. And information about Elster's record that was "unbeknownst" to the officers at the time was included, likely to bolster claims that Elster was probably engaged in criminal activity and a threat (rather than someone who fled because he was scared his vehicle would be impounded and/or he would end up in jail).

The Commission's recent approval of a new policy aimed at curbing pretextual stops like this one may be a good first step in averting similarly fraught encounters in the future. But the commissioners need to be more willing to step up and provide checks where they can. The lengths LAPD went to to distract from Tovar's recklessness by actively villainizing Elster - accusing him of assault with a deadly weapon, throwing him in jail for six months with no bail, then quietly neglecting to charge him - makes clear that LAPD cannot be trusted to police itself.

__________

LAPD hits bystander vehicle with two rounds

Missed opportunities aside for a moment, the commissioners' otherwise rather critical report did pack a few surprises.

For one, it turns out Elster’s vehicle was not the only car Tovar shot.

Incredibly, the report offers the first public acknowledgment from LAPD that Tovar (Officer A, below) managed to hit, but thankfully not pierce, the doors of a passing Lyft driver’s vehicle (the blue vehicle seen above) with two of the last three bullets intended for Elster.

It was not among the things that Chief Michel Moore listed as having been concerned by during his brief report on the shooting to the Commission on February 23, 2021. And there was no mention of it this past January, when both Moore and Mayor Eric Garcetti promised to investigate the department's deadly force policies, practices, and standards after an officer's stray round killed 14-year-old Valentina Orellana Peralta at the North Hollywood Burlington Coat Factory.

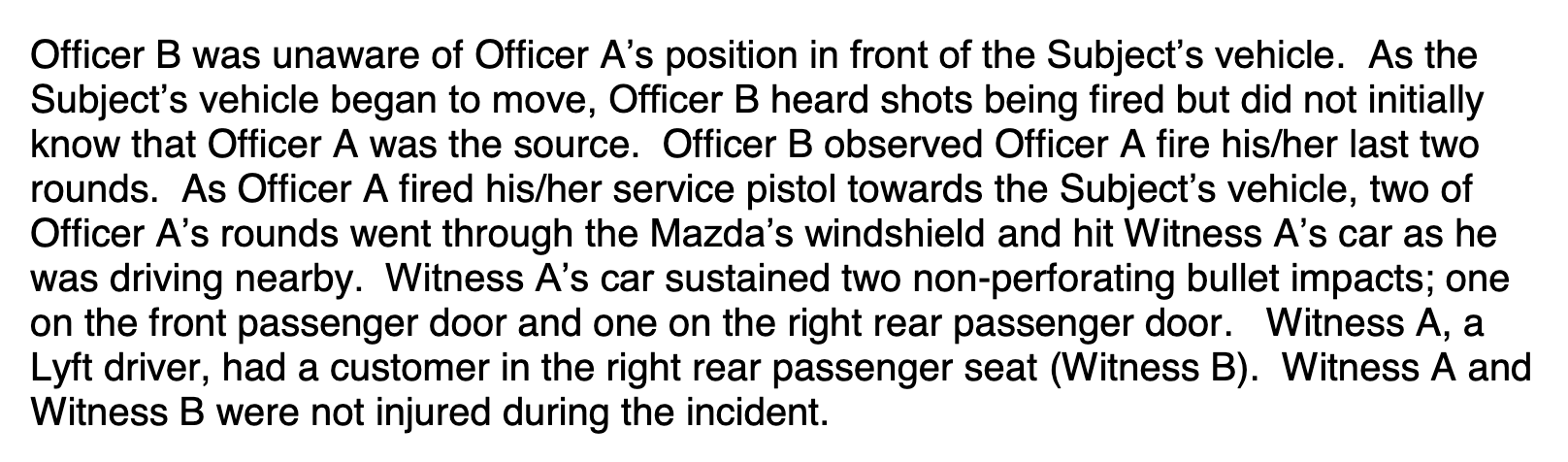

The silence seems all the more astonishing when considering just how many lives Tovar's stray rounds put at risk. Those in the line of fire included Church's Chicken patrons (next door to the lot), residents and passersby along Manchester, and even Tovar's own partner (Officer B, below), who the report describes as being "near" the line of fire when the first round was fired. From the report:

Another surprise in the report was the modest push and pull between LAPD and the Commission. There are multiple points where the BOPC alludes to the significant disconnect between the officers' claims about the threat they believed Elster posed and the tactical decisions made by the officers.

Moore himself had acknowledged being concerned about the officers' tactical decisions at the outset of the stop, so it makes sense that the Commission would also focus on those elements. But the sheer abundance of the contradictory claims included in the report is instructive with regard to just how much pretextual spaghetti LAPD, and Tovar, in particular, threw at the wall to prevent a deeper probe into the incident.

For example, the officers claimed Elster was "impeding ingress and egress to the parking lot," prompting them "to investigate."

Both also claimed to have observed Elster behaving in suspicious and possibly alarming ways, leading them to "believe that [he] may have been engaging in criminal activity." Specifically, they said Elster "appeared 'startled' by the officers' presence," "'slouched backwards'...as if attempting to hide," and, according to Tovar, "looked in the officers’ direction" and was "making 'furtive movements' inside the vehicle, reaching toward his waistband, center console, and floorboard area." Tovar also said he believed Elster was attempting to conceal contraband and/or weapons and that his demeanor mirrored that of subjects he’d dealt with in previous firearm arrests.

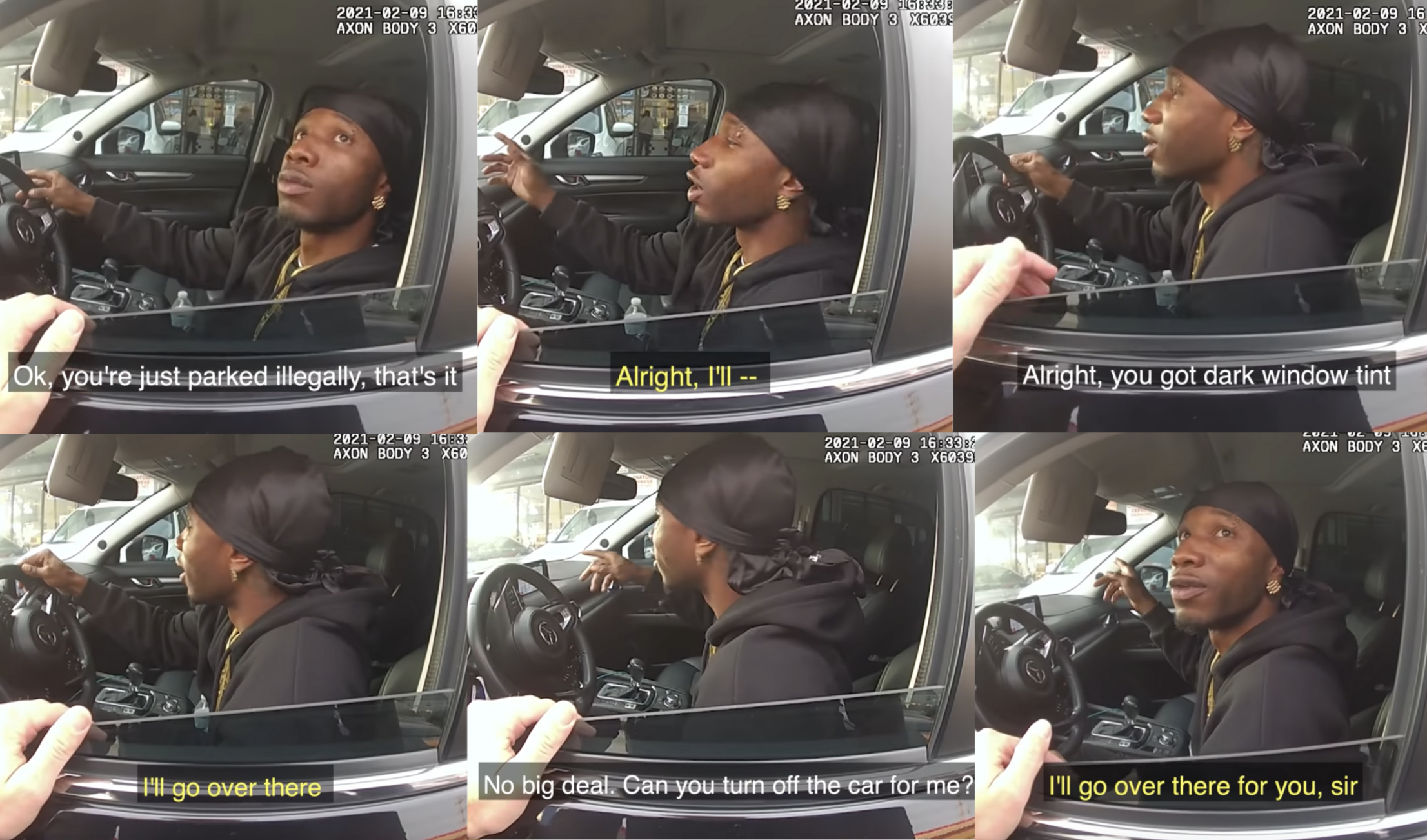

But Tovar had also claimed he had positioned himself in front of Elster's vehicle because of how little space there was between the SUV and the parked vehicles, suggesting Elster had left ample room for lot ingress/egress. Body-worn camera footage from the partner officer confirms this, showing the patrol unit was able to pull into the lot with ease and with several feet to spare between the vehicles.

That footage also shows just how difficult it might have been for either officer – but especially for Tovar, as the passenger in the patrol vehicle – to see Elster reaching for his waistband or attempting to hide contraband when the SUV's tinted windows were closed (below).

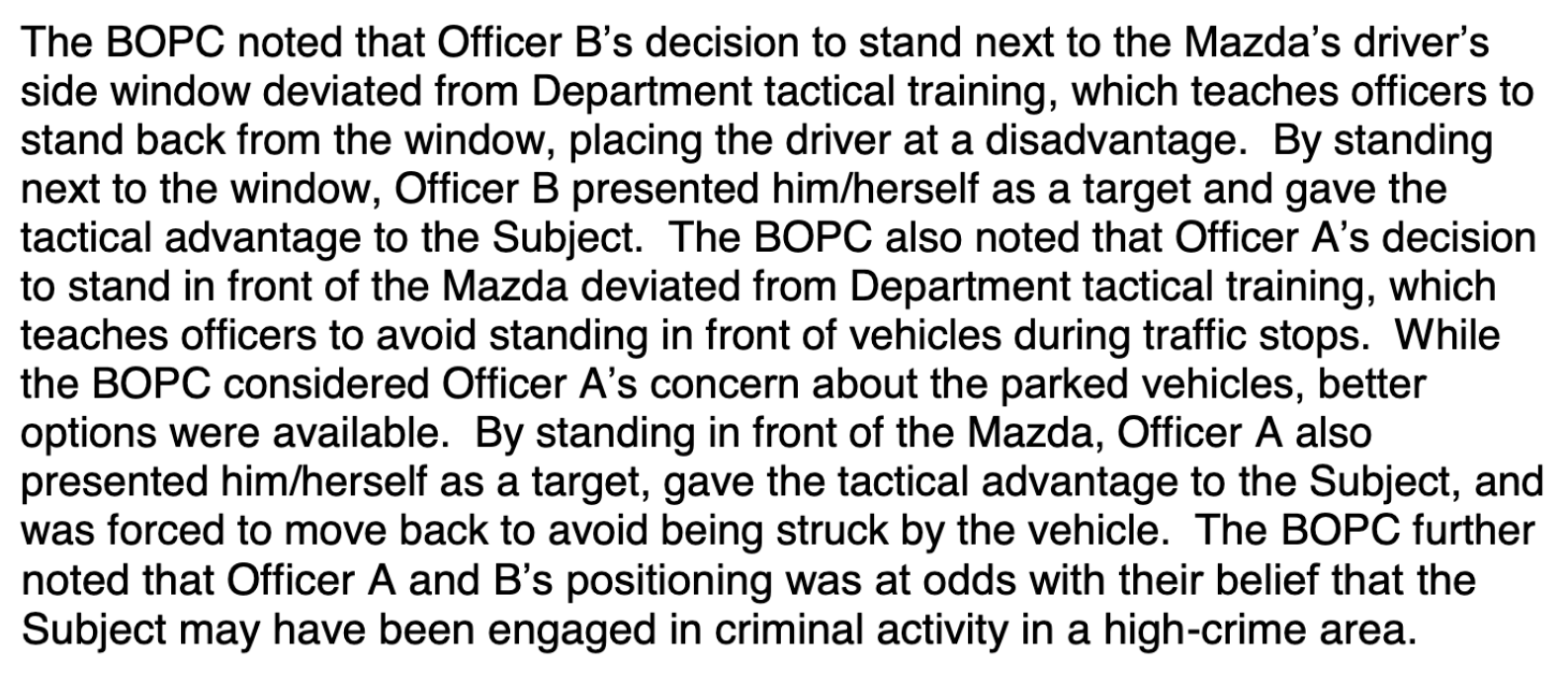

Perhaps most strikingly, and as noted by the Commission, the officers did not have a plan for how to conduct an investigation of someone who, per both officers' descriptions, was potentially armed and/or believed to be in the process of committing a crime in a "high crime area" at a location where both officers said they had “prior knowledge of narcotics, prostitution, and gang activity occurring.”

The officers did not communicate any of the purportedly important information about Elster's behavior to each other before conducting the stop. And, according to Tovar, the partner officer did not even tell Tovar he was going to initiate a stop - he apparently just popped out of the vehicle and immediately approached Elster's window.

To explain his actions, the partner officer reported having hoped to use “the element of surprise to [his] advantage” with Elster.

But the fact that he also took his own partner by surprise - and that neither bothered to radio in the location and intention to conduct a stop - suggests claims about the threat Elster posed were heavily exaggerated.

It also suggests that this sort of pretextual stop - where the officers don't even bother to formulate a plan or clear justification until after the fact - is common enough practice in the area that the officers didn't feel a need to communicate with each other.

For its part, the Commission was more measured in its assessment. But it did indicate that the way that the officers put themselves at a tactical disadvantage - first by not communicating with each other or dispatch and then in the way they positioned both themselves and the patrol unit in relation to Elster's vehicle - "was at odds with [the officers'] belief that the Subject may have been engaged in criminal activity in a high-crime area." From the report:

__________

Bigger discrepancies in officer statements not interrogated

Despite being willing to point out some of the deviations from tactical training and discrepancies in the officers’ statements, the Commission shied away from deeper interrogations of the officers' decision-making processes. They did not explicitly challenge the validity of the pretextual stop itself. Nor did they address the evolution of Tovar’s claims about Elster’s arm movements, the troubling extent to which Elster was painted as suspicious and threatening in order to make Tovar’s claims about fearing for his life seem more plausible, or what either officers' claims indicate with regard to the role of biases.

It would have been an easy case to unpack - the department's efforts to do damage control certainly were transparent enough.

Speaking to press from the Inglewood shopping center where the department first said Elster had barricaded himself (before realizing he had changed clothes and left before LAPD had even arrived), for example, Detective Meghan Aguilar stated that Elster had “backed up toward the officers” during a traffic stop, resulting in the shooting. LAPD tweets that same night reiterated the claim that Elster had endangered both officers. Local outlets subsequently ran with the narrative LAPD provided - ABC7 reported Elster had “backed up toward their cruiser” and KTLA labeled Elster an “assault suspect" that had tried to “run over the officers.”

A week later, LAPD offered a new version of events: the “traffic stop” had been motivated explicitly by the “equipment violation” (not the parking issue). And Elster was now said to have “accelerated” toward just one officer, who was compelled to open fire when Elster “continued driving towards him.” Chief Moore, who said he had reviewed the bodycam footage, then gave the Commission this same accounting of events a week after that.

Inconveniently, however, the footage in question told a different story.

It showed the partner officer telling Elster he had stopped him because of the parking violation; the equipment violation was mentioned half-heartedly - it's almost mumbled in the audio - and only after Elster tried offering to park somewhere else.

More importantly, it also showed that rather than accelerate toward Tovar, Elster had deliberately maneuvered his vehicle away from the officer, accelerating only after Tovar was out of the way and pulling out his service weapon.

So when LAPD posted the critical incident briefing video (below) with that footage a month after the shooting, they had to provide a new story. Which they did.

In this iteration, the stop had been initiated because of both the parking and equipment violations.

But there was also an added twist: LAPD was now claiming that Elster had threatened Tovar with more than just his vehicle.

As he “accelerated toward” Tovar, Captain Stacy Spell explained in the briefing, Elster had “raised his arm," prompting Tovar, “who was standing near the front of Elster’s vehicle,” to fire.

The implication of that extraordinary new piece of information – that Elster had “raised his arm” – was that Elster had had a weapon or gestured in such a way that made Tovar believe that he was armed and intended to do the officer harm.

Tovar later elaborated on that story and the fear it allegedly provoked in him in great detail for investigators.

While he acknowledged he did not see a firearm in Elster's hand, he said he believed Elster might shoot him because Elster had raised his left hand, partially extending his fingers and pointing them at Tovar, “as if he was pointing a firearm.” Tovar also claimed that he fired as many shots as he did - despite the danger to passersby - because Elster continued to hold “his arm straight out and rotated it towards [Tovar]” as he sped away. From the report:

The threatening finger gun was an absolutely necessary detail if Tovar was to have any hope of avoiding reprimand for violating the presumptive threat clause of the moving vehicles policy.

It's also demonstrably bogus.

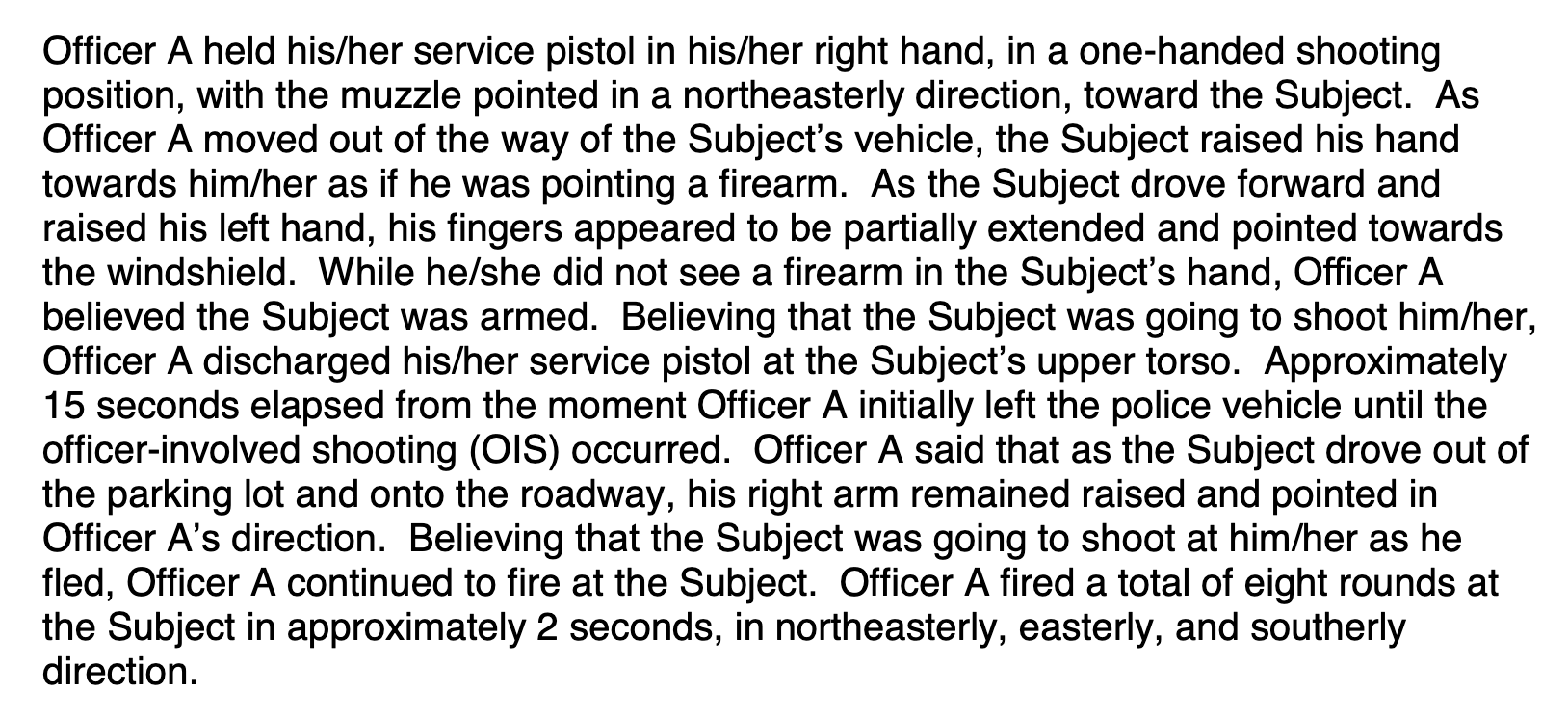

Elster does briefly raise his hand, as seen below, but it is in direct response to seeing Tovar aim a gun at him.

Rather than pointing a finger gun, Elster is making the universal sign for “Please don’t shoot me in the face.”

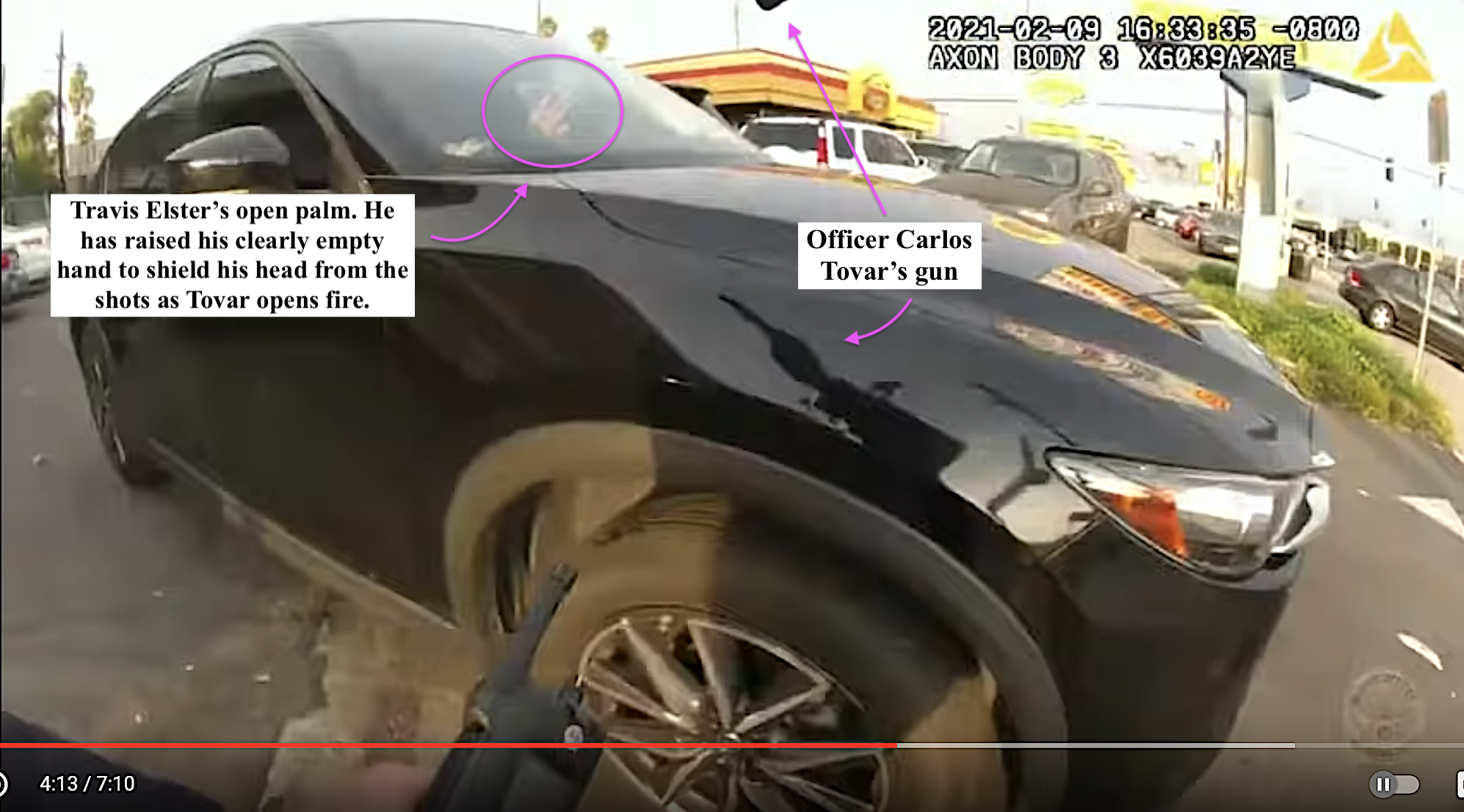

A second later, as he comes abreast of Tovar (who is now pointing the gun directly at him through the passenger window), Elster can be seen ducking and continuing to hold his arm up in a panicked attempt to shield his skull (below).

According to the BOPC report, Tovar claimed "that [he] could still see [Elster's] hand raised and pointed in [his] direction when [he] fired all three of [the] rounds" that hit Elster's passenger side.

In contrast, the footage reveals that there is never a point at which such a gesture is made - Elster's hand is empty and the raised arm is purely defensive - all while he continues to veer to the left to avoid hurting Tovar.

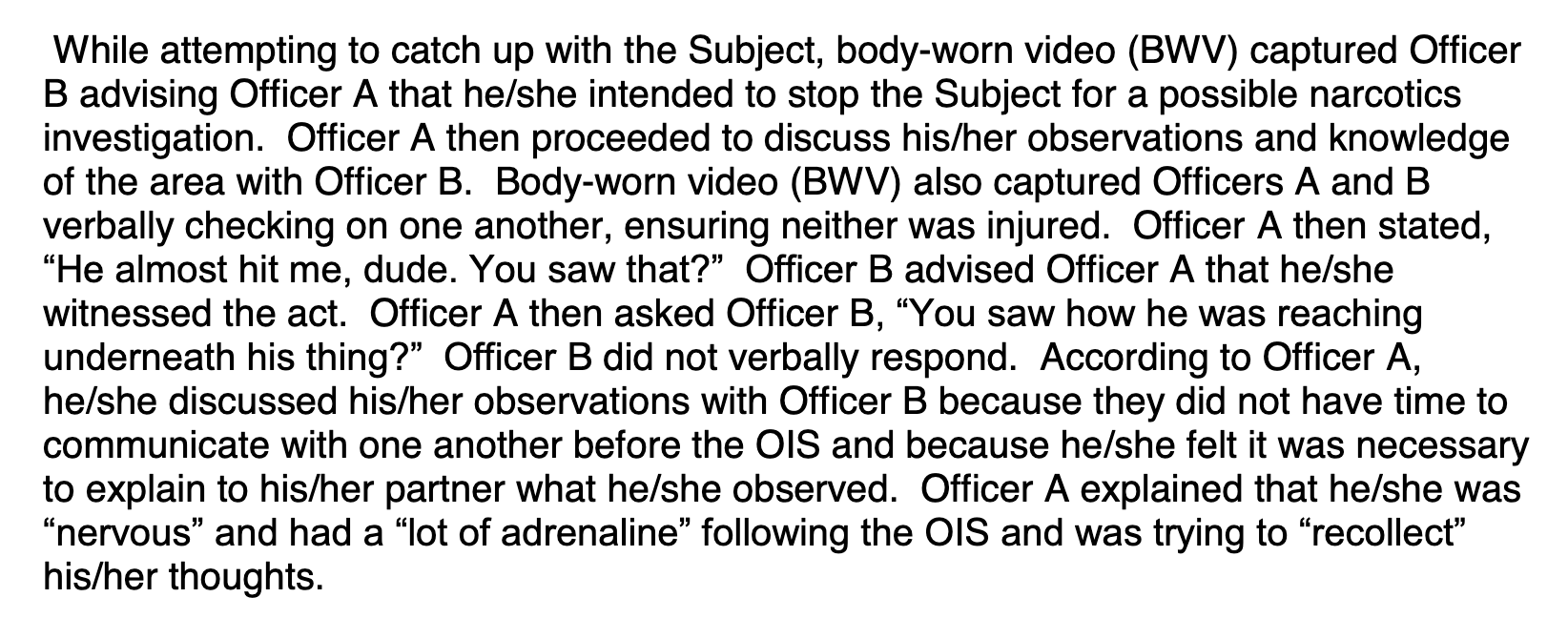

The clearest evidence that Tovar’s claim is baseless might be his own statements immediately following the shooting.

Not having had the chance to review his own body-worn video yet - something officers are allowed to do before making their initial statement to investigators - he appears wholly unaware that he’s seen a threatening finger gun that made him fearful for his life.

So when asked by the Air Unit if Elster had shot at officers, Tovar instead says that Elster had been reaching within the vehicle and was possibly armed with a firearm. Tovar then repeats that version of events to the partner officer as they debrief while following Elster, asking if the officer had seen “how [Elster] was reaching underneath his thing?”

The partner officer did not verbally affirm Tovar's claims about Elster's movements within the vehicle. He had clearly not seen a firearm within reach in the vehicle and had never unholstered his own weapon, even as Elster began to flee.

The inclusion of the full range of Tovar's statements suggests commissioners were aware of at least some of the contradictions in his account.

Yet, despite all evidence to the contrary, they ruled that Tovar had not violated the presumptive threat clause of the moving vehicles policy because he had fired “at the threat [he] perceived in the Subject’s actions" - the threatening finger gun - "and not the threat posed by the vehicle itself.”

__________

See our previous coverage of Elster's case here: Officer Fires 8 Shots at Man Fleeing Pretextual Stop; Evolving LAPD Statements Attempt to Pin Blame on Driver

Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman