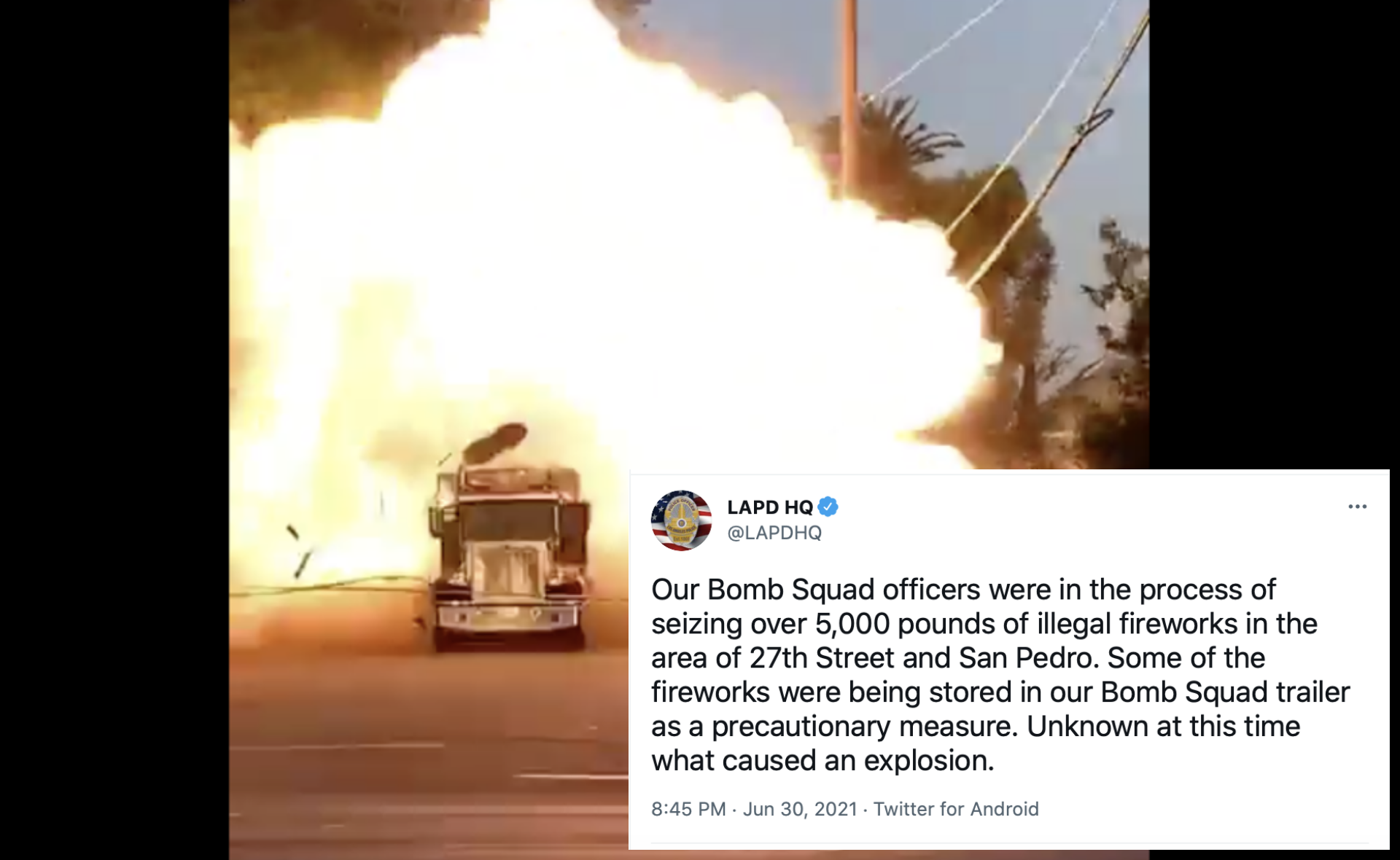

As the dust from the Los Angeles Police Department's catastrophic fireworks detonation continues to settle on the red-tagged homes along E. 27th Street, a slew of questions remain about the June 30 blast that traumatized and temporarily displaced at least 75 people, injured at least 17, shattered windows, shuttered businesses, and destroyed vehicles up and down the street, and contributed to the deaths of elders Auzie Houchins and Ramón Reyes.

Chief among them is why.

Why did LAPD make the decision to detonate explosive material on a residential street in Historic South Central - a formerly redlined lower-income Black and brown community that is also one of the most overcrowded neighborhoods in the country - in the first place?

The question is not meant to diminish the significance of LAPD’s bombshell admission that human error led to the detonation of materials with a net explosive weight (NEW) of approximately 42 pounds in a vessel rated to hold just fifteen.

On the contrary, exploring LAPD's use of the neighborhood as a backdrop allows for questions to be raised about how the eagerness to make this event a spectacle opened the door to such spectacular negligence.

Because if, as Chief Michel Moore stated during the July 19 briefing, LAPD was convinced the explosive materials found posed imminent danger, “not just to those bomb techs but to the citizenry and community,” then very little of what transpired over the course of that day makes any sense.

_________

Whither the urgency?

At the top of the list of puzzling details is LAPD’s apparent underestimation of the size of its fireworks haul by 27,000 pounds.

The cache, originally estimated by LAPD to be 3,000 pounds, then over 5,000 pounds, then, several days later, a shocking 32,000 pounds (as calculated by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF)), would likely constitute the largest such stockpile taken from a private residence in this city's history.[1]

In fact, a cache of that size would exceed the total amount of fireworks confiscated across the entire county annually, which has hovered around 30,000 pounds in recent years.[2]

Within the city of L.A., the stockpiles collected by LAPD have been much smaller. A July 2020 press release put LAPD's seizures for the first six months of that year at just 4,350 pounds total; the final total for the year was around 8,000. In 2019, they had netted a much smaller amount - just 2,350 pounds. Meaning that LAPD should have been acutely aware of the difference between a 5,000-pound stockpile and one more than six times that size.

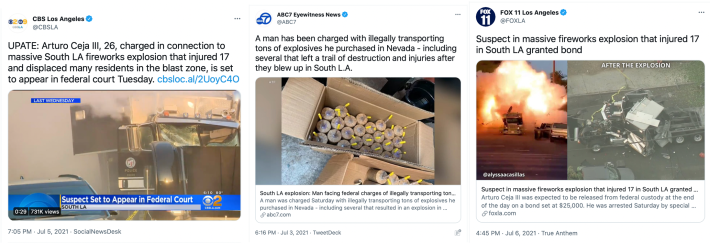

But if LAPD had promptly acknowledged the massive size of the cache found at 26-year-old Arturo Ceja III’s residence, then they likely would have had to explain how and why they did not take greater precautions to protect the community.

The department has made a point of taking such steps before. After discovering seven tons of fireworks in a warehouse near 800 N. Spring Street in 2004, for example, they evacuated 250 people from the surrounding blocks. The operation required the closure of multiple streets, tangling rush-hour traffic. The motivation for the evacuation, Fire Captain Bill Wick said at the time, was the fear that a change in heat or humidity could ignite some of the fireworks, kicking off a disastrous chain reaction.

This past March, the ignition of commercial grade fireworks stored in an Ontario home (below) showed just what such a chain reaction could look like in a residential neighborhood. The blast killed two people and left several others homeless. Footage captured by a next door neighbor, seen here, also provided a terrifying window into just how powerfully blast waves could shake up the insides of adjacent homes and their inhabitants.

Since the June 30 explosion, Moore has decried how "countless community members...were senselessly exposed to the clear and present danger created by the alleged criminal actions of Mr. Arturo Ceja when he chose to store more than sixteen tons of fireworks and illegal explosives at his house on a residential street." The decision to charge Ceja with child endangerment is also meant to suggest that the mere presence of the fireworks put the life of Ceja's 10-year-old brother (who was also living in the home) at great risk. The federal complaint alludes to the danger as well, stating Ceja had “stored [the fireworks] outside and in an unsafe manner, namely under unsecured tents and next to cooking grills,” implying the neighborhood was one smoked hot dog away from armageddon.

Yet on that day, the discovery of two sets of "improvised explosives” - both of which LAPD claims were leaking explosive materials and were too volatile to be physically weighed or safely transported from the scene for fear of accidental ignition - does not appear to have triggered any additional urgency.

Instead, photos released by the LAPD/ATF seem to indicate that, in contrast to best practices cited by Moore, LAPD actively jostled the 44 soda can-sized devices multiple times. And they did so while the reportedly leaky devices were still surrounded by tons of ignitable ignitables (below). [Less is known about the handling of the smaller M-80-type devices. Those photos have yet to be released and the count seems to still be in flux: the night of the blast, Moore said there were around 200; on July 3, the Justice Department (citing the criminal complaint) stated there were 140; at the briefing on the 19th, Moore declared there were 280; then, on July 28, Moore went back to the original claim that there were "200-plus."]

Similarly, although LAPD has stated multiple times that, per protocol, it set up a 300-foot perimeter around the explosive threat, footage from the outlets called to document how expertly LAPD commandeered the cache suggests otherwise.

On busy San Pedro, for example, buses, trucks, and passenger vehicles are seen rumbling unimpeded past the stacks and stacks of fireworks that were approximately 100 feet from Ceja's backyard stockpile (below). This went on all day, even though the last of the volatile materials were not loaded and locked in the TCV until just ten minutes prior to the 7:37 p.m. detonation.

Evacuations also appear to have been similarly haphazard.

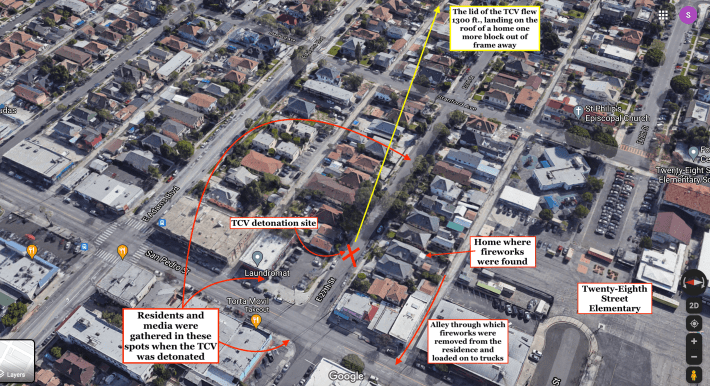

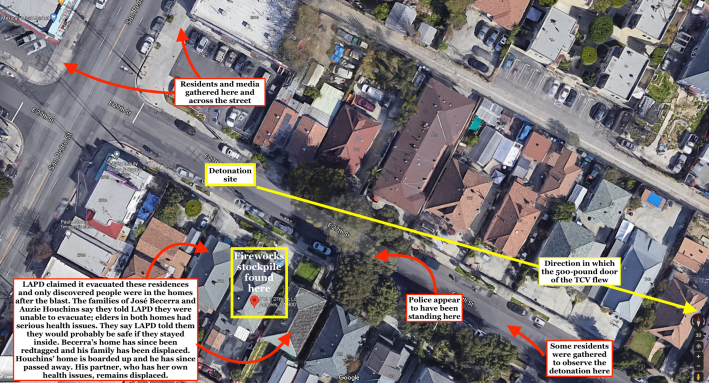

Throughout the day, LAPD did do some door-knocking to notify residents of the activity on the street, but the notifications were limited to just the immediate vicinity. During the briefing on the 19th, Moore confirmed that officers had first focused on evacuating the two homes on either side of 716 E. 27th (see below). Later, they attempted to evacuate three additional homes on the south side of the street. Finally, he said, efforts were made to notify some of those on the north side, and businesses were told their patrons should move away from the windows.

Elders with significant health issues lived on either side of Ceja’s home. Those families say LAPD told them they would probably be safe if they remained indoors, even though the TCV was parked less than 50 feet from José Becerra’s front door (above).

The blast destroyed Becerra's home, which was directly west of Ceja’s, and sent several members of his family to the hospital with cuts, scrapes, facial fractures, concussions, and a ruptured ear drum. [See Fox11 reporter Koco McAboy's interview with Becerra, below.]

The home of Auzie Houchins and Lorna Hairston, directly east of Ceja’s, was also seriously damaged, temporarily displacing the couple. Houchins, 72, who was disabled, has since passed away from what Hairston believes was the added stress of having his life so violently upended. [See her interviews with Spectrum News’ Kate Cagle, here and here.]

Others who answered their doors claimed LAPD did not explain why they were being asked to leave their homes. Other neighbors either never heard LAPD come to the door or were outside the set of households notified. Still others engaged later in the day seemed to be under the impression that there was going to be some sort of fireworks-related demonstration and were ready to capture it for posterity on their phones.

Consequently, a number of families were standing in the open air to the east, about 200-250 feet away on E. 27th during the detonation (see map above). Another group of residents, including small children, can be seen gathered on the west side of San Pedro, directly across from and less than 200 feet away from the TCV (see the first few seconds of Alyssa Casillas’ footage, below).

WATCH: A bystander caught the moment a planned fireworks explosion rocked South L.A. Wednesday night. Police were trying to detonate illegal fireworks they had seized, but the blast was more powerful than expected. (Credit: Alyssa Casillas) Details here: https://t.co/QPnFKMtmRx pic.twitter.com/A5egGsW0Fs

— NBC 7 San Diego (@nbcsandiego) July 1, 2021

And contrary to Chief Moore’s claims that pedestrians were moved across San Pedro to safety before the charges were set off, Univisión’s camera operator captured a group of shocked bystanders and their children outside the laundromat (just 75-100 feet away from the blast, below) immediately following the detonation.

This seemingly lax approach to both the evacuation and the detonation stands in stark contrast to how LAPD handled the Vietnam-era hand grenades family members found in a deceased relative's North Hollywood garage in 2018. In that instance, LAPD evacuated the streets and homes within a two-block radius around Clybourn and Clark. The bomb squad then examined and removed four or five grenades, later detonating them a little over two miles away and at some distance from residences, inside Valley Village Park. Residents reported being able to return home after about two hours.

On the morning after the E. 27th St. blast, Lieutenant Raul Jovel chose to blame the failed evacuation effort on the injured residents, claiming that they hadn't answered their doors.

WATCH: LAPD official says some residents didn't answer their doors when officers went door-to-door evacuating the neighborhood prior to the fireworks detonation. Some of those people were then injured in the ensuing explosion. https://t.co/CfrvR5N2vL pic.twitter.com/huZxIlS9tL

— KCAL News (@kcalnews) July 1, 2021

Three weeks later, rather than acknowledge that those injured were older, disabled, had nowhere to evacuate to, and had been told they could shelter in place, Chief Moore echoed Jovel's message, essentially telling the Police Commission the real issue is that people don't listen to law enforcement.

LAPD would look at whether officers told people the evacuation was voluntary, he said, but "one of the largest challenges we have is that evacuations are often dismissed, in the sense of they're ignored or people find it inconvenient and [follow] their own rationale." Noting that arresting people would be counterproductive to the larger goal of protecting life and property, Moore said it was important that LAPD clearly communicate the consequences of ignoring a mandatory evacuation order.

The fault lay with the evacuees, regardless of their circumstances, in other words. And they needed to understand "if they choose to refuse to leave that they are not just breaking the law, that they're subject to loss of life or serious injury as a result."

_________

"This is one of the most difficult periods of time [to be a police officer]" - Chief Moore (three weeks post-blast)

In the days and weeks following the blast, LAPD has remained steadfast in its claim that the 41 previous detonations using the TCV were done in neighborhoods of all income levels across the city.

What set this particular event apart, of course, was that LAPD had called in just about every press outlet in town to document it. And that the department did not take enough care to ensure that a Black and brown community was not further harmed in the process.

It was supposed to have been a feel-good story - a showcase for both the technical expertise of the LAPD and the kinds of big-ticket items critics have called for to be slashed from its $1.76 billion operating budget. As Sky9's Desmond Shaw told his colleagues at CBS2, their helicopter had been hovering overhead, "expecting to see some routine thing and to kind of get the shot that was gonna be the bookend to this [fireworks seizure] story." Namely, "this armored canister probably shaking a little bit and smoke coming out at the end of it." Just the fact that officers comprised the bulk of the injured - ten total were hurt, with nine taken to the hospital, along with one ATF agent[4] - suggests that LAPD had undertaken this operation with an expectation of maximum spectacle and minimum risk.

Lord knows they could have used the win.

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, the ongoing calls for the reimagining of public safety, and continued concerns about how poorly LAPD has handled protests, journalists, traffic stops, the unhoused, COVID-19, the gang database, concerns about racial profiling, the clearing of encampments from Echo Park, victims of violence, and racism within the ranks, to name a few, the department has spent most of the last year-plus on the defensive.

Day to day, it has turned to social media to make the case that it does indeed provide a valuable service and to push back against proposed reforms.

Part of that effort has entailed leaning heavily into fearmongering narratives about crime and chaos. Department, division, and individual officer feeds alike have subsequently been clogged with gun porn and detailed explanations of how minor traffic violations were leveraged into vehicle searches in the name of crime prevention.

But at this particular moment - which Moore recently described as “one of the most difficult,” “unfair,” and “deeply disturbing” times to be a police officer - opportunities for morale-boosting displays of heroism and community trust-building have proven more elusive.

This is especially true in Historic South Central, a community LAPD has repressively policed since L.A.’s earliest days.

In the mid-20th century, officers looked the other way when roving gangs of whites made incursions into the neighborhood to assault Black and brown residents. They also declined to investigate fire-bombings and cross-burnings at the homes of the Black people who dared to move outside overcrowded redlined zones. Then, in 1969 the neighborhood was targeted for the first major use of SWAT: a raid on (and detonation of explosives on the roof of) the Black Panthers’ L.A. headquarters at 41st and Central. More than 350 officers participated in the effort to serve a search warrant for illegal weapons at a site occupied by just thirteen Panthers, kicking off a four-hour gun battle.

In the intervening years, the ongoing harassment of residents and the controversial killings of community members like 38-year-old Daniel Hernández - gunned down by influencer and officer Toni McBride at 32nd and San Pedro in 2020 - have done little to help build trust.

Perhaps a major fireworks haul capped off with an on-site detonation seemed like a way to turn the tide in that regard - an opportunity for LAPD to demonstrate the lengths it would go to to protect the community from harm. And where better to do it than in the district of Councilmember Curren Price, who co-authored last year's motion to cut $150 million from the LAPD budget?

What is knowable is that media were informed of the presence of volatile materials around 4 p.m., per a tweet from the L.A. Times' Kevin Rector. The fire department got word around 6 p.m. And news about the plan to detonate the materials broke half an hour later, about an hour before the blast (below). [5]

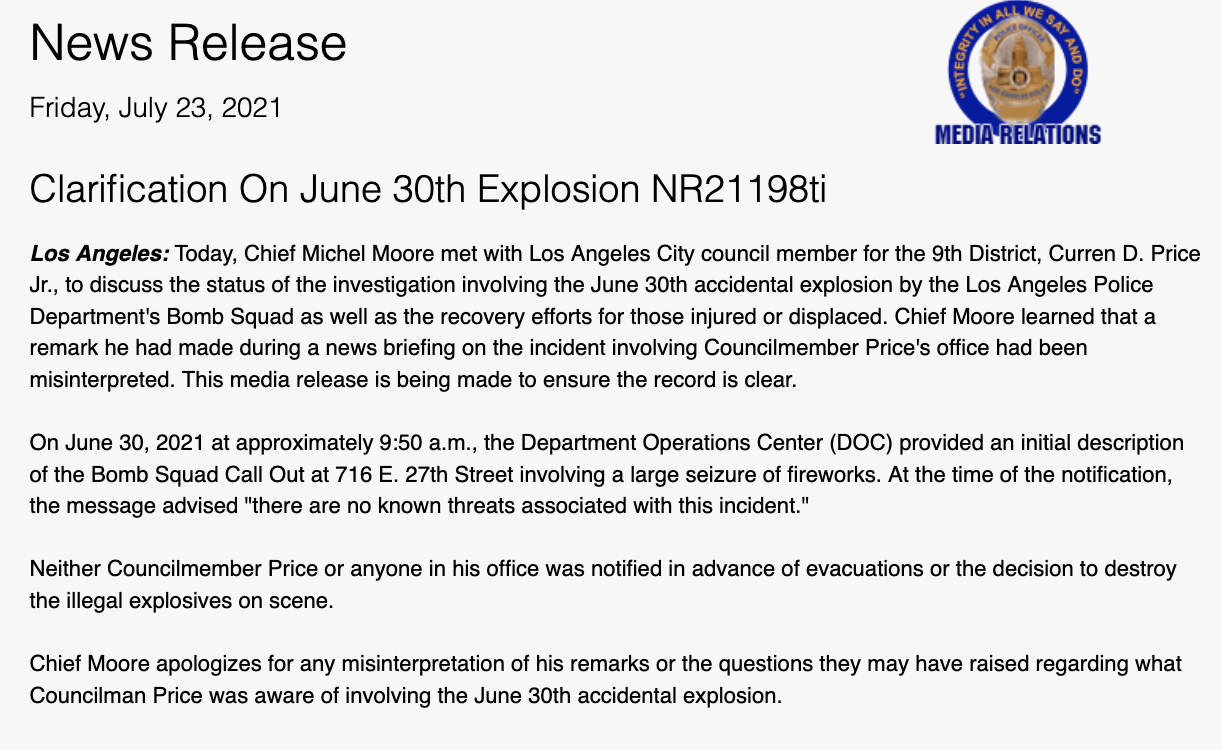

But in a rather pointed breach of protocol, LAPD chose not to alert the councilmember's office about the explosive materials, evacuations, or planned detonation.

LAPD Detective Aguilar talks about the illegal fireworks found today in a home near East 27th Street and San Pedro Street in Los Angeles, CA. @latimes pic.twitter.com/aZRvFgUfok

— Francine Orr/LATimes (@francineorr) July 1, 2021

When questioned about the lack of communication with Price's office at the Police Commission on July 20, Moore sounded annoyed. “The council office was notified via deputy, uh, counsel, uh, field operative, if you will, at approximately 10 o'clock that morning relative to the response,” he said.

Although he went on to say he "[didn't] differ whether there could have, should have been additional follow up with the council office when determination that the detonation of some devices would be required at that location,” the commissioners seemed to accept Moore's vague statement to mean that Price had indeed received sufficient notification.

Price wasn't having it.

The only notification his office got was a mid-morning email from LAPD to the wider city family. It stated the bomb squad was retrieving 500 boxes of fireworks from a home and that there were "no known threats associated with this incident." [See that email on Jonathan Peltz’ (KNOCK-LA) twitter here.]

At city council the following week, he asked Moore to again clarify on record that his office was not informed and to explain why his office was shut out of that loop. Moore did confirm the failure to notify Price, but could not explain the protocol breach. He said he would have Deputy Chief Al Labrada look into that, and asked Labrada (who was also on the call) if he had anything to add.

Labrada had already gotten an earful about the protocol breach while seated next to Price at the July 12 community meeting about the blast. At the time, however, the Deputy Chief had seemed more preoccupied with putting angry residents and their supporters in their place, telling them this was a moment to come together, not "heckle" LAPD or "get in each other's faces." He'd expressed similar sentiments in a tweet a few days prior to that meeting, minimizing community anger, positioning LAPD as a victim, and taking a swing at Black Lives Matter for good measure (below). It was a more subtle dig than the shot he had fired the summer before, when he openly accused "so called community leaders" of encouraging destruction and then "blam[ing] our officers for trying to control the chaos." But the resentment was palpable all the same.

How that defensiveness will shape Labrada’s inquiry into the decision-making that day remains to be seen. He made no additional comment on Moore’s assessment at council and the discussion quickly moved on.

_________

"This was not a stable laboratory environment" - Chief Moore explaining the miscalculation of net explosive weights

Even if LAPD was more focused on the optics and politics than the explosives, it remains difficult to comprehend how they concluded these materials should be detonated all at once. Especially given the quantity they had on their hands.

Bomb squad protocol does indeed allow for an estimation of the NEW of explosive materials in lieu of physically putting them on a scale in cases where volatility is a concern. This is what LAPD says happened here: because the materials were deemed too volatile to be weighed, bomb technicians x-rayed the devices and sliced into them to take samples. Then, according to Moore, the techs relied on those x-rays, further visual inspection, and their “many years of experience in gathering and dealing with an unstable and dangerous item” to estimate the net explosive weights.

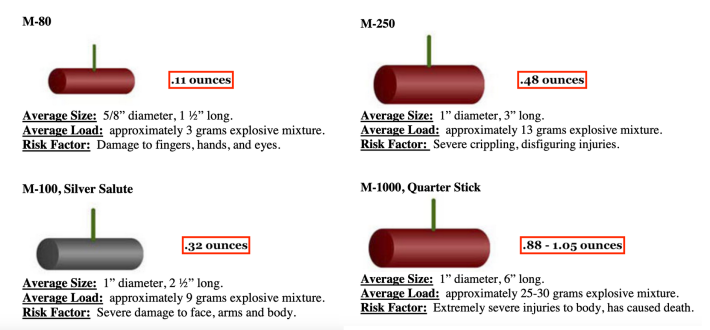

Those years of experience led the techs to wrongly conclude that each of the 280 smaller devices, which Moore described as similar to rolls of quarters, held half an ounce of flash powder (approximately 8.8lbs total). The 44 soda can-sized devices were judged to hold 1.5 ounces of flash powder each (a total of about 4.1lbs). The relationship between the weight of flash powder and its net explosive weight is not one to one, however, so while the total amount of explosive material was estimated to be around thirteen pounds, the NEW itself was estimated to be just under ten pounds - a figure Moore first cited during the press briefing the night of the blast.

Notably, it appears that the bomb squad's years of experience did not include time spent on the Google, where one can readily find young fireworks enthusiasts from around the world gleefully blowing up devices very similar to the soda can-sized ones seized (below).

Even a cursory search suggests that the 100 gram Profi Cannon Shot "Big Boy" and its variants (e.g. Little Joe and Mega Boy 125) are common enough that expert bomb techs should have been familiar with them.

Most importantly, the techs should have immediately recognized the estimate of just 1.5 ounces of flash powder as being alarmingly low: similar devices tend to carry at least 3.5 ounces/100 grams.

The ATF’s National Response Team later estimated the larger devices were even more densely packed with flash powder, containing five ounces each (13.75 pounds total). The smaller devices were found to contain 1.37 ounces each (24 pounds total). Together, they yielded a total NEW of 30.25 pounds - double the explosive weight the TCV was rated for.

The bomb techs didn’t just misguesstimate that net explosive weight by over 20 pounds, however. They also managed to drastically undereyeball the NEW of the countercharges that they themselves constructed.

Countercharges have known net explosive weights and are usually carefully calibrated as part of the effort to create a controlled detonation. Yet somehow the LAPD’s calculations of their own known materials were off by over five pounds. At a NEW of 11.77 pounds (rather than the 6.5 pounds the bomb squad had originally estimated), the countercharges alone accounted for 80 percent of the capacity of the TCV.

Moore had no answers for how any of this could have happened.

Instead, he said they were currently reviewing both the extent to which the techs had adhered to existing protocols and whether those protocols and standards reflected best practices. People would be held accountable if they did not meet expectations, he said. But if it turned out the standards themselves were to blame, people would not be disciplined for following the rules.

He then testily pointed to the difficult conditions he says the bomb squad were working under.

LAPD is home to “some of the finest, if not the finest, bomb techs in the world” who are “constantly training, honing their craft” and who are looked to by others around the globe “for training, insight, and awareness of how to conduct [their own bomb squad] operations,” he said.

But the “handling of [fireworks] is not like Play-doh… There's a lot of stress involved in this. This was a hot day. This was an event where they put fans in order to try to cool these fireworks from going off. This was not a stable laboratory environment.”

Moore did not speak to the fact that few, if any, assessments the bomb squad are called upon to make take place in stable laboratory environments. Or why a team trained to take on terrorist threats would not have been prepared for stressful conditions.

Eyeballing weights was hard, he argued. “The difference between a half ounce and 1.37 ounces - I don't know if you and I can discern that.”

The ATF fact sheet police departments around the country rely on (below) would suggest we can.

A half-ounce of explosive mixture is the typical amount found in an M-250, a device that is about three inches long and can cause severe, crippling injuries. The quarter stick is three inches longer (or sometimes has a larger diameter, see below), carries double the explosive mixture, and can kill you. A device carrying 1.37 ounces of flash powder would be just under the equivalent of both of these combined and, besides obliterating your extremities, might also helpfully create a shallow crater for your ashes to fall into.

All of which is to say Moore is asking Angelenos to believe that LAPD's globally renowned bomb squad - technicians that protocol has long dictated be called to the scene when M-80-type devices are found - is less familiar with common fireworks' explosive weights than your average teen pyro.

_________

Please disperse - there's nothing to reform here

Instead of seeking answers to any of these questions when Chief Moore made an appearance at city council on July 28, councilmember, longshot mayoral candidate, and former LAPD officer Joe Buscaino demanded to know the status of the charges against Arturo Ceja. “Are we anticipating holding him accountable for taking a role in this tragedy?”

The question played into the narrative that Moore had been pushing since the night of the blast and had repeated to council just minutes earlier (below). Namely, that Ceja's "reckless actions" had brought this disaster on and that LAPD had saved the community from a far worse fate. “By the grace of God, we were told of [Ceja's stockpile] and there wasn’t a detonation of that material prior to our intervention,” he said.

It's not the first time LAPD has done this kind of scapegoating to cover for an egregious error.

Last year, when veteran officer Frank Hernández was caught on tape punching an unhoused, unarmed man nearly 20 times in an unprovoked attack, law enforcement sources gave demonstrably false information to NBC4’s Investigative Team in order to paint the victim, Richard Castillo, as an armed aggressor. The body cam footage, released the next day, made clear why LAPD was so concerned. Not only had Hernández taunted and goaded a passive Castillo before launching himself onto Castillo's back, he had tried to get his partner to tase Castillo (because he was too tired to keep punching him), snarled at witnesses, and then lied to the backup officers about how the altercation had begun.

LAPD tried the same sleight of hand this past February, after officer Carlos Tovar fired eight wildly out-of-policy shots at 30-year-old Travis Elster as he fled a pretextual traffic stop in a South Central parking lot. First, they claimed Elster had driven his vehicle directly at the officer. When body cam footage showed Elster had explicitly maneuvered his vehicle to avoid the officer, LAPD claimed Elster had raised his hand toward Tovar in a threatening way, causing the officer to open fire.

That claim was also demonstrably untrue.

But the allegations were successful in focusing attention on Elster’s decision to flee and the implication that he had something to hide. Which meant attention was directed away from deeper structural questions about the LAPD’s habit of aggressively profiling young Black men and of how disruptive pretextual stops are to their lives. Worst of all, the claim that Elster intended to harm a police officer has allowed LAPD to keep him locked up without bail for months, effectively silencing him.

LAPD is leveraging Arturo Ceja in much the same way.

Charging him with 18715a - a Deadly Weapons code targeting those working with explosives with the intent to cause harm - set his bail at half a million dollars. It also carries much heftier penalties than typical fireworks charges and implies Ceja intended to hurt his neighbors. [Normally, even large stockpiles over 5,000 pounds fall under Health and Safety codes.]

The seriousness of the charge is meant to lend legitimacy to claims LAPD has made regarding the urgency of the threat.

Conveniently, it also allows LAPD to frame the botched detonation as a largely technical issue that can be resolved with better checklists, documentation, explosives training, and protocols.

To that end, Moore has pointed to the adjustments LAPD has already made to some of its protocols and the removal of five members of the bomb squad from the field as a demonstration of the department’s commitment to ensuring this type of “accident” never happens again.

That messaging seems to have paid off. Mayor Eric Garcetti recently told Spectrum News that he had faith in Moore's ability to address this "bad mistake" and in how good the chief was at “demanding that people learn from mistakes.”

"Whether it's retraining, whether it's changing policies, or holding people accountable, all of those should be on the table, and I support the chief's process," he said.

If the mayor has been troubled by the fact that the chief’s process also entails putting as much distance as possible between the department and the harm inflicted upon community members – e.g. telling the Police Commission that he believed the deaths of Houchins and Reyes were unrelated to the blast and the result of “more long-standing underlying health issues” – it has not been readily apparent.

Exactly one month after the botched detonation, Garcetti was just a mile and a half south of E. 27th Street, helping LAPD repair its image.

LAPD, back on the hunt for feel-good stories, had given CBS2 the “exclusive” on how the more visible and community-oriented presence of South Park Community Safety Partnership (CSP) officers had brought down crime, built stronger relationships, and created an atmosphere of "shared accountability."

It was the same story about the South Park CSP that LAPD had told to ABC7 back in April, just two weeks after the disastrous effort to clear encampments from Echo Park made national headlines.

Where the April story honed in on community trust and relationships (to address critiques of the Echo Park operation), the July 30 story was laser-focused on communicating CSP (and, by extension, LAPD) provided a vital service and was a deeply valued presence in councilmember Price’s district.

Perhaps the story recycling would have been less obvious – or at least felt less cynical – if the report had actually dug into the intensive and genuinely difficult work involved building relationships over time. Instead, it tapped the same South Park community member for a testimonial about how "all police officers are not bad." And it featured pointed messaging from both LAPD and the mayor on the danger of abolishing the police and the importance of mutual trust.

It is hard to know what mutual trust looks like when LAPD’s very first public step after blasting the street to smithereens was to take to twitter and actively push misinformation (below).

Since then, LAPD has been evasive with a number of basic details, including the manufacturer of the total containment vessel and specifics on where and how it has been used. At the July 19 briefing, Moore even went so far as to declare he didn't have information on who manufactured the vessel. [It is NABCO, per LAPD's own website and news footage from that day where the logo is clearly seen.]

Given LAPD's lack of transparency, community members seeking a fuller accounting of that day and any implications for institutional reform will have to pin their hopes on the Inspector General’s investigation, which is currently underway.

In the meanwhile, they are making do with emergency grants from councilmember Price's office, a portion of which had to be drawn from the funds cut from LAPD’s budget last year as part of the initiative to reimagine public safety.

_________

Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman

Threads/videos that may assist with understanding the timeline better:

- 6/30 - Twitter thread capturing emerging images and news on the blast in real time

- 6/30 - LAPD, LAFD briefing the night of the blast

- 7/2 - Thread and link to the July 2 press briefing with ATF and the city's emergency management department

- 7/8 - Thread and link to July 8 briefing with displaced family and representatives of Councilmember Price's office

- 7/12 - Thread on the July 12 community meeting; meeting video on Unión del Barrio's facebook page here, here

- 7/19 - LAPD briefing July 19 (where LAPD acknowledges the miscalculation of the net explosive weights)

- 7/20 -The July 20 Police Commission meeting (because of summer recess, it was first meeting after the blast)

- 7/21 - Councilmember Price announces emergency fund, partnership with CRCD, some community member testimony

- 7/28 - Councilmember Price and Chief Moore at City Council, July 28

Footnotes

[1] Neither LAPD nor ATF has clarified why LAPD's initial estimates were so off, considering how big a haul 16 tons is (and assuming all fireworks were found on site). A scouring of past news reports suggests hauls of more than five or seven thousand pounds tend to be found in warehouses or scattered across two or more locations. And although the discovery of 1,000, 2,000, or even 5,000 pounds of fireworks have become something of a routine summer ritual for both LAPD and LASD, stockpiles of tens of thousands of pounds are more rare. One notable exception was a 1996 raid in Gardena that turned up fifteen tons of fireworks in a warehouse, an amount described by the L.A. Times as "five to six times the amount of explosives used in the catastrophic Oklahoma City and Saudi Arabian bombings."

[2] In 2016, LAPD and LASD together confiscated just over 30,000 pounds of fireworks; in 2019, the total haul was also around 30,000 pounds. Even in San Bernardino County, which borders Pahrump, Nevada, where so many of the fireworks are bought by California vendors, the total seizures have fluctuated between 40,000 and 60,000 pounds.

[3] It has been difficult to get answers about where three of the four photos above came from. Multiple outlets have published the two on the left, crediting the ATF (see the top left shot credited to the ATF via AP on CBS8, Yahoo News, and Spectrum News; the bottom left shot was spotted on ABC7, NBC4 and in the Yakima Herald. The photo at bottom right was graciously provided by Kate Cagle of Spectrum News; she tweeted out the photo, which had been mounted on posterboard for the LAPD's July 19 press briefing. When all four photos were requested from LAPD, however, the PIO sent the photo at top right and said to ask ATF for the others. ATF says it did not distribute any photos.

[4] Listen to the L.A. Fire radio response to the scene and discovery of the injured, here. LAFD had been advised of the detonation around 6 p.m. and had one truck, one ambulance, and one battalion chief on the scene on standby in the event something went wrong. Of note are the last few minutes, where it is communicated that LAPD has requested LAFD to hurry up so the area can be cordoned off as a crime scene. LAFD is heard bristling: “Yeah, we’re not going to be rushed…We’re going to get this right and then we’re going to get out of the way.”

[5] It should be noted LAPD received the tip about the stockpile at 8:45 a.m., not at noon, as Detective Aguilar stated, and that both LAPD and ATF had already been on the scene for a few hours by noon.

[6] Though it is true TCVs are used for on-site detonations (including in residential neighborhoods) when materials are thought to be too volatile to move, in contrast to Moore's claim, they can also be used to move suspicious devices, as this piece in The Verge details.