Nipsey Hussle Understood Cities Better than You. Why Didn’t You Know Who He Was?

5:45 AM PDT on August 15, 2019

Jermaine Welch shows off the shoe he had custom painted in Nipsey Hussle’s honor while waiting for Hussle’s funeral procession to pass through the intersection at Crenshaw and Slauson on April 11. Hussle was killed in front of his store, The Marathon, on March 31. Sahra Sulaiman/Streetsblog L.A.

“Age fourteen on up - my whole life took place on these four corners,” rapper, artist, entrepreneur, innovator, and urban visionary Ermias “Nipsey Hussle” Asghedom mused as he surveyed the street from the parking lot of the strip mall at Crenshaw and Slauson during a 2010 interview with Current TV (below). “This really was my foundation.”

He had come up hustling mixtapes out of the trunk of his car there. Squabbling there. Hatching business plans and dreaming big with some of the crew he hung out with there. Laying the groundwork for his All Money In movement and record label there. Opening several shops there (including his flagship, The Marathon, in 2017). Incorporating that corner into his brand to the point of becoming practically synonymous with Crenshaw and Slauson. And reeducating the youth, the community, and the world about what was possible at that corner.

A member of the Rollin' 60s since age 15, however, he had primarily been viewed by the city as a source of blight - not a product of it. Consequently, he and his crew had been hassled, chased out of, raided, or arrested there more times than he reported being able to remember.

The fight to claim place and space at Crenshaw and Slauson would become one of the defining struggles of his life.

It was also one of the defining struggles in his community, rooted in the policies and practices implemented to uphold segregation and the city’s historic efforts to deny South Central residents, and the Black community, in particular, ownership over their own streets.

Hussle chronicled what it meant for lower-income Black youth on the margins to come of age within that context over the course of a dozen mixtapes, nearly 50 singles, a handful of compilation albums, a grammy-nominated studio album, and dozens of hours’ worth of interviews recorded over nearly fifteen years.

Among the many things he spoke on were how "reachin' for the stars will have you reachin' through the bars." How when "the judge triple white and he hate your Blackness/slam the gavel with a racist passion," every step forward would be met with a purposeful shove two steps back. How the streets were "cold outside/ain't no hope outside," and how the stress of the paranoia, struggle, and constant loss he endured would leave him wrestling with "night demons" long after he left the streets. How he had to "live it up when we get it, 'cause it never last." And how there was little use in imploring, "Come to my hood; I'll show you desperation/Kids dead at 13 like Devin Brown, with no explanation,"1 because the only thing that being “from where homicide boost the economy" seemed to incentivize was the construction of more prisons.

For the community to claim what was theirs, Hussle realized, they would have to forge their own path forward. Remaining fiercely independent, never compromising his voice, retaining full ownership over his artistry, brand, and output, uplifting those around him, and being the blueprint for others to follow was his contribution to that larger mission.

“I’m not a preacher or none of that, you know," he told Current TV (above). But "whenever I talk to my homeboys, I tell ‘em, like, ‘Yeah, man, you know this [hustling] ain’t about nothing. What we doin’ out here is a stepping stone to get to something legitimate.’"

In the wake of his tragic death at the corner that raised him this past March 31, many of those touched by his message have vowed to continue that marathon.

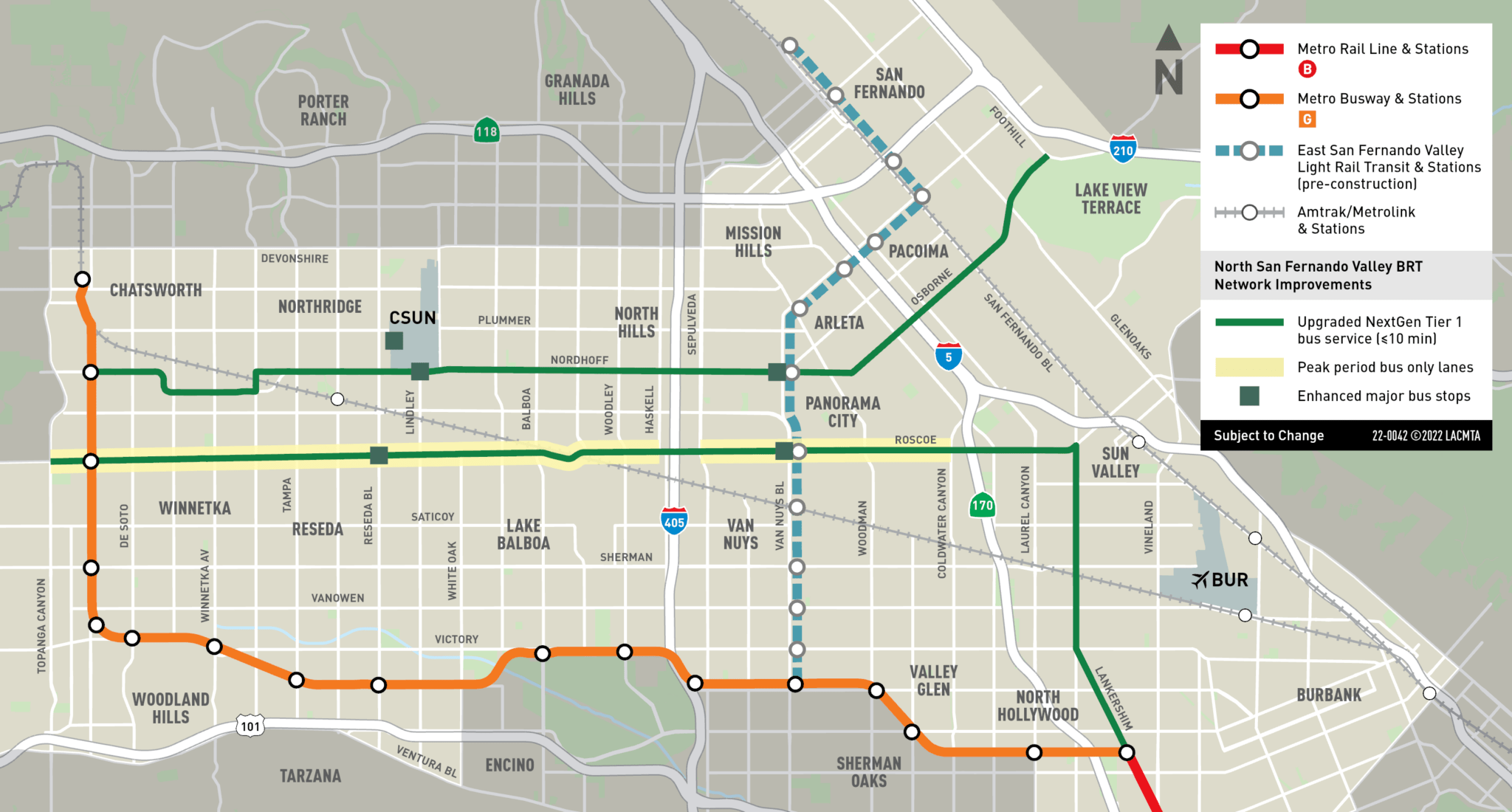

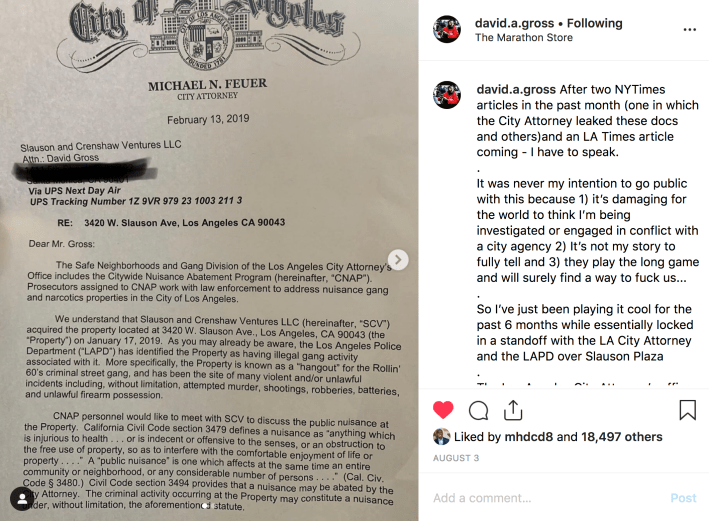

Law enforcement and the city attorney, on the other hand, have apparently decided they cannot abide a monument to one of the best-known faces of the Rollin' 60s being the first thing greeting visitors arriving in L.A. via the soon-to-be-open Crenshaw Line.

A nuisance abatement letter sent this past February let Hussle and his team know that the city was continuing the formal eviction effort it had launched last fall, after a man was beaten and stabbed at The Marathon on September 14.

Surveillance video suggesting the possibility that the victim, a member of the Rollin' 60s, had entered the store with the intention of engaging in a violent confrontation (and the subsequent charging of Hussle's brother, Samiel "Blacc Sam" Asghedom, with attempted murder of that man) offered the city an opportunity to pressure the building's owners to evict Hussle in the name of gang abatement.

The district attorney dropped the charges against Blacc Sam a few weeks later, however, suggesting he had been acting in self defense, according to documents obtained by the L.A. Times. And the brothers, along with business partner David Gross, bought the building outright at the end of 2018.

The team's plan to build Nipsey Hussle Tower there, adding affordable housing and more retail to the site, has the potential to fundamentally change the nature of that corner.

Yet the city has not stood down.

In an instagram post this past August 3, Gross, a real estate developer, founder of Vector90, and co-founder of Our Opportunity investment fund, detailed his frustration at the leaking of information about the ongoing investigation to The New York Times and the strong-arm tactics he said the city and LAPD were subjecting him to behind the scenes.

"This shit is a cold game and then some," Gross wrote of the "maniacal zeal" of the city attorney's effort to oust them from the site. "This system is a mindless, heartless, relentless machine designed to keep us locked into some systems (jails and courts) and out of others (capital markets and property ownership). It sounds crazy and conspiratorial, only because it is."

This struggle for the right to dominion - both real and metaphorical - over Crenshaw and Slauson speaks to the larger battles currently playing out across the country between urban centers and the communities of color they worked so hard to leave behind.

Nipsey's own story, cobbled together here from fifteen years' worth of music and interviews, underscores just how all-consuming that fight can be when your city categorizes you as blight and denies you the ability to take access to your own streets for granted.

It's a deeper dive than anything we've ever published at Streetsblog. But the fact that so many of those who think about, plan for, and write about cities did not have the faintest idea who Nipsey Hussle was or why he mattered could not go unaddressed.

If we're to have any hope of creating vibrant urban landscapes capable of nurturing the next generation of Nipseys, the story of L.A., and of cities more generally, cannot continue to be driven by privileged narrators who have yet to reckon with how their own communities benefited from the aggressive suppression of his.

We hope you'll listen to what he had to say.

_______

They tried to cover up the history of what we was - Cali

Given the deep contradiction between his aspirations for his 'hood and what he saw around him, Hussle’s interest in L.A.’s segregationist history is not surprising.

He had been born into the community in 1985, just as the cumulative effects of decades of disinvestment, disenfranchisement, and repressive policing were hitting their stride.

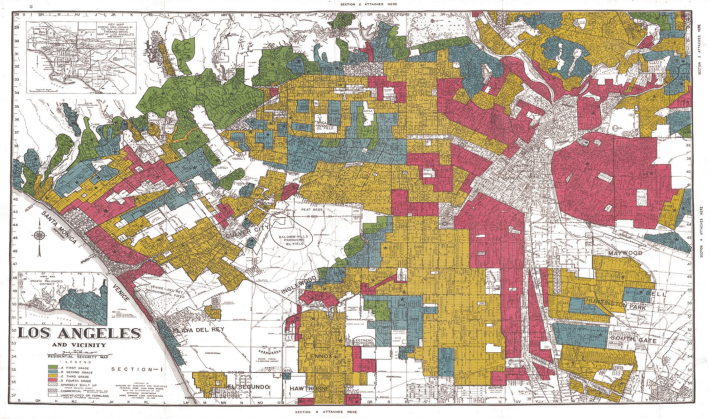

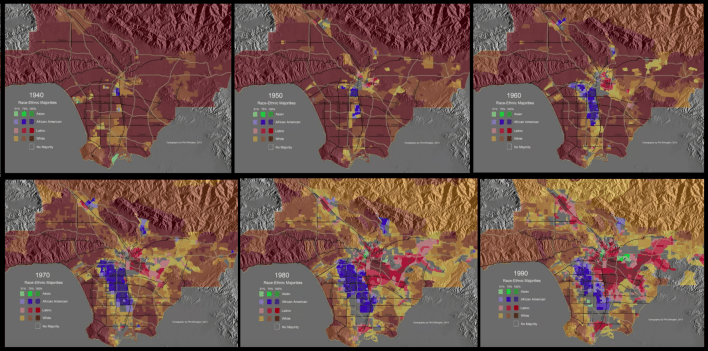

Racially restrictive covenants (deed stipulations that ensured a property would not be sold to non-whites, particularly Black people) might have been struck down in 1948, but whites’ impulse to self-segregate remained strong. Most fled South Central in the 1950s and ‘60s as the booming Black population moved out of overcrowded redlined zones into southwest L.A.

When the 10 freeway went up across South Central’s northern edge (deliberately tearing through the heart of some of the city’s wealthiest Black neighborhoods, to boot), there was no mistaking the message being sent to the newly walled-off residents: You are really on your own now.

The community got the message.

Their abandonment, coupled with massive job losses and cutbacks in resources for social programs in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, ensured that Hussle and his peers would be born into the community just as it was falling into deep disrepair and distress.

Drug use had been in decline when then-president Ronald Reagan's desire to get tough on "crime" - code for Black and brown folks - manifested in the ramping up of the War on Drugs. By convincing the public that inner cities were in crisis in 1982, he had managed to secure the funding necessary to arm law enforcement to the teeth. In the process, he had primed suburbanites to welcome the dramatic scenes of inner city homes being battered by tanks (below) that would play out on their television screens just a few years later.

Between June and December of 1984, SWAT and narcotics officers conducted raids of “68 fortified [crack] rock houses.” They deployed the infamous battering ram - constructed from surplus military parts left over from the ‘84 Olympics and immortalized in song by Toddy Tee - in four of those raids, including one of a Pacoima home where police recovered less than a tenth of a gram of cocaine. Police ratcheted up their operations over the next nine months, raiding 450 “suspected rock houses” that netted them a total of 10 pounds of cocaine. And although the battering ram would not be used in ‘85, the potential for the LAPD to punch a hole through the door or the wall (or knock the home down outright) would keep residents in embattled neighborhoods fearful of losing everything for years to come.

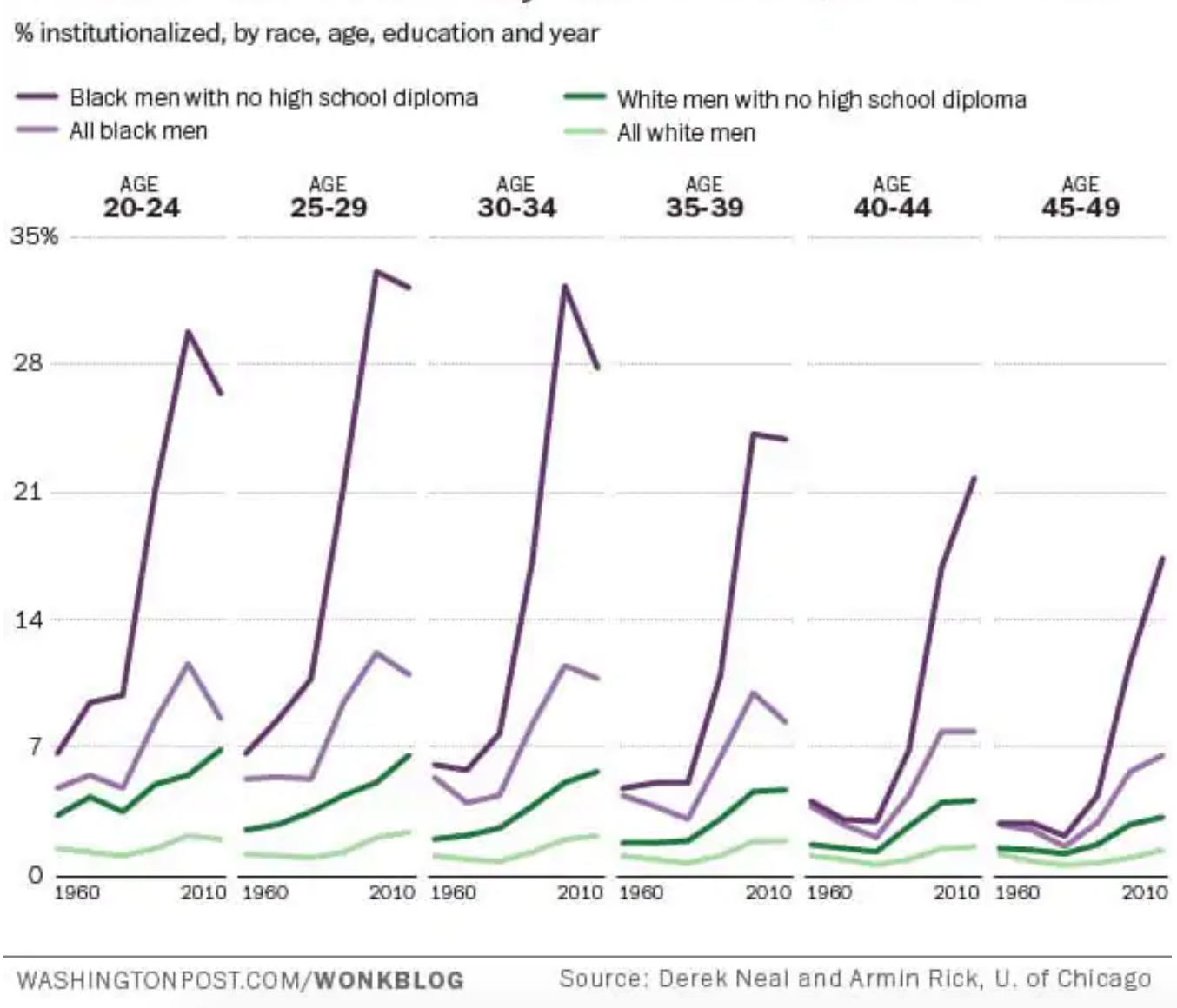

In 1986, the establishment of harsh mandatory minimums for more than two dozen drug offenses put drug addicts and small-time crack hustlers in the ‘hood in the same category with major cocaine dealers.

Not that the LAPD needed the added push to round folks up. Then-Chief Daryl Gates was notoriously of the opinion that casual drug users “ought to be taken out and shot” because “in a war,” even casual drug use “is treason.” But the tougher mandatory sentences - like five years for five grams of crack - did make it a lot easier to begin the work of disappearing a generation of Black fathers, uncles, sons, and brothers from the streets.

So did the death of 27-year-old Karen Toshima in January of 1988.

Up until that point, whites and the well-to-do had largely been insulated from the turmoil that was killing Black and brown youth in record numbers in South Central. The loss of a young woman out with friends in Westwood - felled by a bullet a member of the Rollin' 60s had intended for a rival - shattered that complacency. All eyes finally turned southward.

Police patrols were immediately tripled around Westwood and 30 officers were assigned to investigate her case. A $25,000 reward was proposed in City Council to aid in finding her killer. Within two weeks of her death, the city had hired 150 new police officers and would hire over 500 more within the next six months. The District Attorney’s office leveraged Toshima’s case to get $1.5 million in federal funds for gang prevention work and to boost their gang unit staff from 16 to 50. The $6 million in emergency funds the city rapidly pulled together was put towards additional patrols and the ramping up of Operation Hammer - a program that, over the course of the next year, would see thousands of young, largely Black, men rounded up in massive sweeps and interrogated simply for being in a neighborhood with gang and drug activity.

The state jumped into action with the Street Terrorism Enforcement and Prevention Act - emergency legislation that made active participation in a criminal street gang a crime (with a penalty of up to three years). Crimes said to be committed “for the benefit of” a gang saw anywhere from two years to life tacked onto a sentence, depending on the severity of the felony (at least, until the year 2000, when gang enhancement penalties were boosted substantially, despite both their questionable constitutionality and problematic application).

Gates also got to work at gaslighting the South Central community. Just two weeks after Toshima's death, he penned an op-ed in the L.A. Times claiming the LAPD treated the murders of their children with the same urgency and attention it was now giving the Toshima case.

And because the world now wanted to know what on earth a Crip was, 48 Hours headed to South Central (including to Crenshaw and Slauson to talk to the Rollin' 60s) to investigate Black gangs.

Airing five months after Toshima’s death, “On Gang Street” invited viewers sitting in the safety of their suburban homes and gated communities to witness “two days and two nights of terrorism on America’s streets...set in a scary America many of us don’t know… [on] a battleground where some citizens still stand and fight on the side of good. And others simply fight.”

It did not ask those viewers to contemplate how or why the urban cores they isolated and protested against school busing programs for might have arrived at such a state. Or how their own party drug habits might be contributing to the forces tearing inner cities apart while they themselves remained largely exempt from any real consequences.

Instead, the somber introduction suggested said viewers were right to have fled inner cities when they did, given the state of humanity they were about to witness.

What followed were scenes of law enforcement detaining, talking down to, searching, and even mocking groups of mostly Black male youth. Reporters asking youth who were clearly fronting for the cameras why they were so intent on hurting their own people. And interventionists and concerned community members proclaiming there was no sense of morality left in the community and that the youth were akin to monsters.

If viewers had had any lingering doubts about Black youth being dangerous, lawless, impervious to reason, amoral, or singularly focused on killing each other for sport, the report appears to have been intended to put those doubts to rest.

Which is not to say that the gang problems were not deeply entrenched or that members of the community were not also desperate for change and actively dedicating every waking hour to filling in the growing gaps in services to assist their neighbors. Both had long been true at that point.

But at every turn, 48 Hours missed opportunities to contextualize the crisis the community was experiencing.

Black gangs hadn’t come out of nowhere.

They had their roots in self-help and community defense efforts dating back to the mid-20th century, when roving gangs of whites like the Spook Hunters stormed into Black and brown neighborhoods and assaulted residents or attacked them when they moved through white neighborhoods. Police, who also actively demeaned and brutalized the community, generally refused to assist residents or investigate the firebombings of the homes of non-white folks who moved out of redlined areas.

It was only after whites had fled South Central that these informal neighborhood defense groups would begin to evolve into their more current form. Some would take sartorial and political cues from the Black Panthers, following in the footsteps of Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter, who had been a member of the Slauson Renegades before launching the Southern California chapter of the Panthers in 1968.

But after witnessing the violent suppression of the Panthers, the deepening of disinvestment, and the drying up of both resources and jobs in subsequent years, gangs quickly became more insular. More about survival. And more of a bulwark against alienation, police brutality, and insecurity in the public space - especially once drugs and guns began flooding in in the 1980s.2

Ignoring the conditions gangs were a response to and focusing on the choices made by individual gang members confirmed harmful biases whites held regarding the inherent criminality of the community.

It also absolved the reporters of having to challenge officers’ tactics or treatment of the youth. After all, if most youth were lost causes and only responded to fear, as the officers claimed, what other recourse did police have, right?

“Growing up on Gang Street means growing up in a bleak corner of America where the normal rules don’t apply,” Dan Rather intoned in closing. “Where too many young people seem to feel they have no stake in law or order or decency or hard work.”

“And that’s not just a problem for the police,” he concluded. “That’s a problem for all of us.”

_______

Since it's just n*ggas killing n*ggas/You just turn prison to a business - Payback

Except it wasn’t a problem for “all of us.”

It was more a problem to keep away from a particular “us.”

Where life in Westwood would eventually return to a slightly more hyper-vigilant normal after Toshima’s death (and one where merchants contemplated ways to more aggressively limit access to Black patrons), South Central residents would pay an increasingly steep price for Westwood’s - and white L.A.’s - quest for peace of mind.

Take the infamous raid at 39th and Dalton, where as many as 88 officers descended on two apartment buildings to search for drugs on August 1, 1988. Over the course of several hours that night, officers “smashed furniture, punched holes in walls, destroyed family photos, ripped down cabinet doors, slashed sofas, shattered mirrors, hammered toilets to porcelain shards, doused clothing with bleach, emptied refrigerators,” tossed a vacuum cleaner through a window, painted LAPD graffiti on the walls, left ten adults and twelve minors homeless, detained passersby and made them lie face down on the sidewalk, delivered beat-downs to a few youth, and arrested at least 33 people before eventually releasing all but five of them with no charges. (Those five would never be prosecuted, either.)

Or consider a year’s worth of headlines like, “Arrests Top 850 as Anti-Gang Drive Continues” and “Police Arrest 1,092 in Weekend Sweeps; Gang Killings Continue,” that were meant to make it sound like the city was taking gang issues seriously but which glossed over the consequences of giving the LAPD (and, eventually, federal agencies) license to behave like an occupying force.

And then consider that there was so little interest in tracking the handful of serial killers preying on vulnerable Black women in different areas of South L.A. in the '80s that community members, led by human rights activist Margaret Prescod, had to launch their own coalition just to try to get the LAPD to see the victims it labeled “No Human Involved” as actual people.

Given that 1988 was also the year of the Willie Horton attack ad and ramped-up tough-on-crime rhetoric stoking whites’ fears of Black men, it was no surprise that the community didn’t get very far when they tried to alert the wider public to what they were experiencing at the hands of the LAPD.

Formal complaints against the LAPD would continue to climb that year, but few officers would ever be prosecuted. NWA would release “F*ck tha Police” that same summer, only to see it banned from the airwaves by people more concerned about the alleged violence of the lyrics than the actual violence the artists were shining a light on.

“Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what’s going on in the ‘hood,” Doughboy (played by NWA's Ice Cube) memorably lamented in Boyz n the Hood (1991) after watching the evening news report on violence overseas but make no mention of the brother he had just lost to a drive-by.

Gates, for his part, was not interested in hearing how the blanket criminalization of the community exacerbated its sense of isolation. Or how much more attractive it made the gangs offering solidarity, protection, and the promise of respect to fatalistic youth desperate for some sense of control in the face of the chaos around them.

Even after the verdict in the Rodney King case in 1992 sent residents roiling into the streets to lodge the biggest collective scream for justice the city had ever seen, there was little substantive change. Few of the city’s promises to do better by South Central after the uprising would be kept. And a record 412 people would be murdered in the South Bureau alone the following year.

Nipsey Hussle was just eight years old then, taking everything in and about to try his hand at writing for the first time. He would subsequently spend his most formative years trying to navigate the long shadows those events - and all those broken promises - cast.

_______

Now my name all in the news/Trippin' on all of my moves - Hussle and Motivate

That the massive outpouring of grief over Hussle’s passing caught legacy media (and most of whiter, wealthier L.A.) completely off guard was, sadly, to be expected.

But it did offer a powerful reminder of just how deeply segregated L.A. remains. And how significant a role tired tropes deployed by many of those very same outlets had played in enforcing that state of affairs.

With some exceptions, the limited mainstream coverage of Nipsey prior to his passing often played into negative stereotypes about the criminality of rappers and relied heavily on law enforcement to provide the framing.

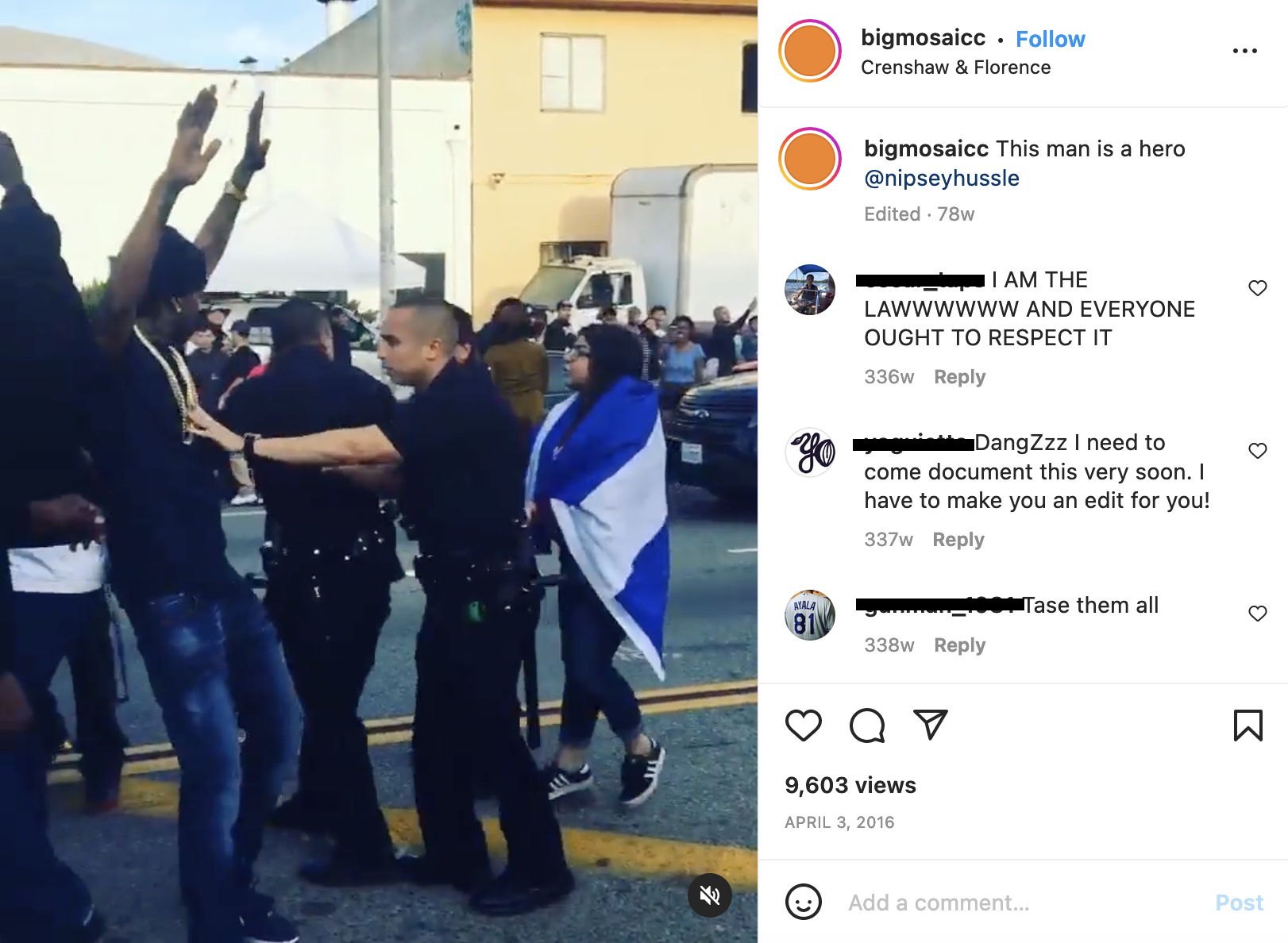

Take, for example, his arrest two days before he was to perform in the Made in America festival back in 2014. The encounter began with police checking to see whether someone in the crew Hussle was getting food with was in violation of their probation. Soon, the entire party had been cuffed and detained by enough officers to field a football team. Hussle's clothing store was then searched for the next few hours. Hussle (who was not the target of the original probation check) ended the night by being put into the back of a police car (see video of the detention and arrest here).

NBC Los Angeles' coverage of the arrest omitted most of the details regarding how the probation check was carried out. No witnesses were interviewed. No questions were raised about the frequency, value, or validity of the constant checks Hussle and his associates were subjected to. The claim by law enforcement that Hussle had obstructed a peace officer was taken at face value.

For his part, Hussle put out an official statement the next day claiming his arrest was “unjust and without cause.” He also expressed outrage on instagram (below) at having had to watch officers rifle through his store for hours yet again, only to turn up nothing.

For its part, the L.A. Times’ follow-up story reported being unable to get a statement from the LAPD. They ignored Hussle's perspective completely, including only his tweet reassuring fans that he was still planning to make his scheduled performances that weekend.

But when cops arrested him in Burbank in 2015 (a search conducted during a traffic stop turned up codeine for which he did not have a prescription), the Times ran a photo from that 2014 arrest. Rather than note he had just left the studio, they declared “the [Burbank] arrest wasn't his first run-in with law enforcement.”

The tendency of outlets to rely on law enforcement could also come in handy for the LAPD.

When a man was badly beaten during an altercation between members of the Rollin' 60s at The Marathon last September, details were scant. The disappearance of both the alleged victim and perpetrator before either police or ABC7 had arrived and the unwillingness of witnesses from inside the store to speak meant that the news crew had little material to work with.

The incident did, however, give the LAPD the opportunity to enlist ABC7's help in communicating that Hussle's presence in the strip mall was tied to violence - something that would lend support to the nuisance abatement case the LAPD was building against him.

ABC7 was more than obliging, adding a backdrop of Hussle being chased by the police (taken from the video for “Hussle and Motivate”) to the segment, despite the reporter's acknowledgement that Hussle did not appear to have had any involvement in the incident.

So it was predictable that mainstream outlets scrambling to cover Hussle’s passing would have to wrestle with how to categorize the man whose value had largely been filtered through law enforcement’s perspective of his encounters with law enforcement.

Still, the narratives they landed on were jarring.

Rather than a gifted child and good person who had been faced with limited options and hard choices as a youth, he was the gangster with a heart of gold who had renounced his scofflaw past. A changed man who wanted to help others see the error of their ways. And, most mystifyingly, a friend to the LAPD:

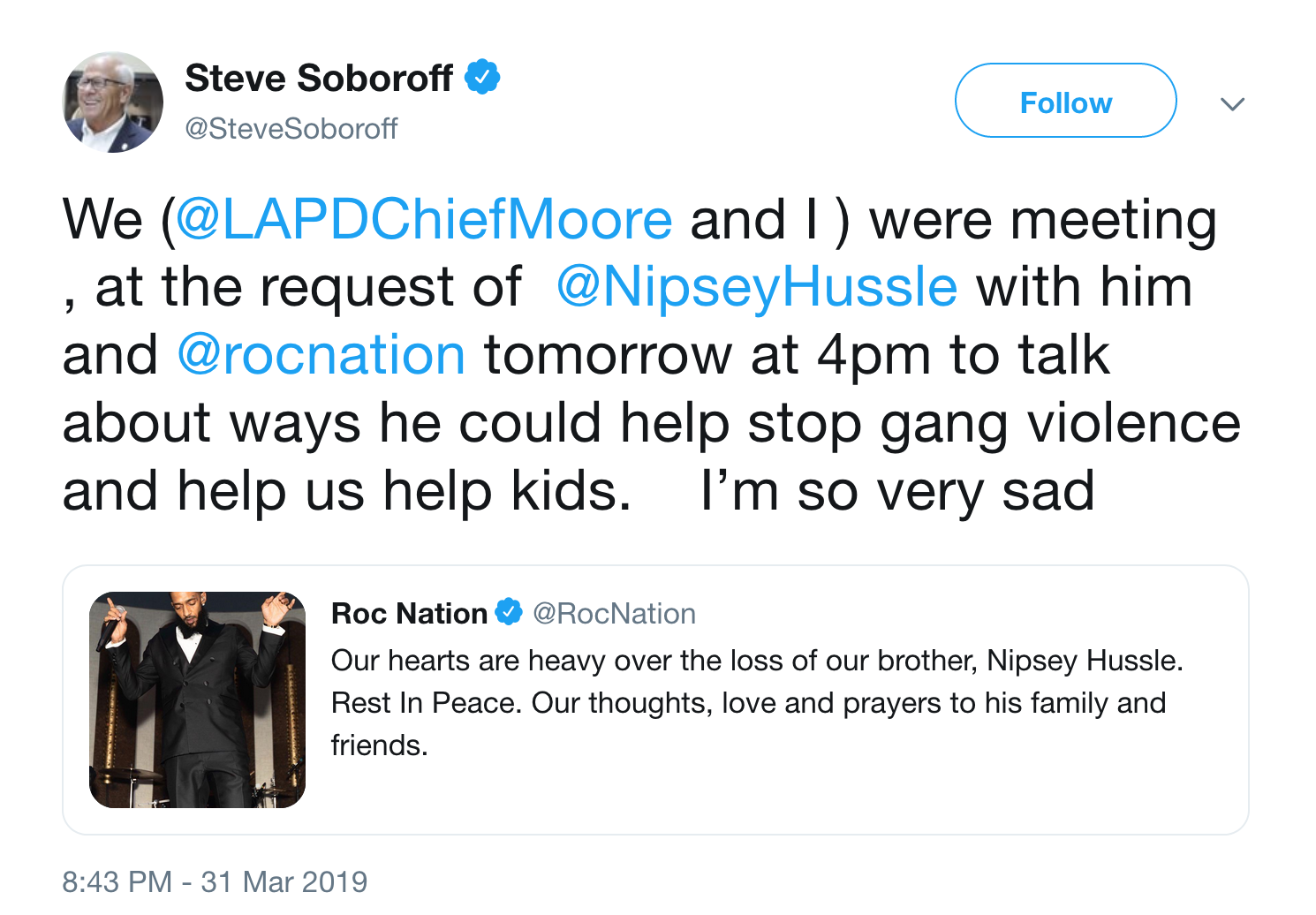

Outlets' seizure on L.A. Police Commissioner Steve Soboroff’s characterization of the meeting planned with Hussle (above) allowed law enforcement to continue shaping perceptions of his legacy.

The idea that he sought to partner with the department to “help stop gang violence” - a framing that implies that the community is the source of the problem - was made the lede again and again and again, suggesting Hussle had come around to the LAPD’s way of seeing things.

That was unlikely.

The man who had so succinctly explained in "Blue Laces" that “The streets is cold, turn innocents to militants,” who had taught youth how to rethink their relationship to the streets, and who had set himself apart with his interest in building solidarity across 'hoods already knew how to address gang violence. He'd walked that talk since the earliest days of his career, as he and Cobby Supreme explained back in 2009 (below), while on tour with The Game (a Blood).

What he wanted to engage the LAPD about (in addition to addressing gang violence) was how to “help improve communication, relationships, and work towards changing the culture and dialogue between LAPD and the inner city."

Policing, in other words.

He was concerned about how his community was policed.

And he was looking both to hear about the kinds of concrete steps the LAPD planned to take to build trust with his community and to find points of convergence where he could help facilitate that process.

It is also notable that the letter to Soboroff was sent on February 26, just two weeks after the notice of abatement claiming The Marathon was a magnet for illegal activity had arrived from the city attorney's office. Meaning Hussle may have also been challenging law enforcement to prove they were sincerely concerned about the community and not just pursuing a vendetta against him.

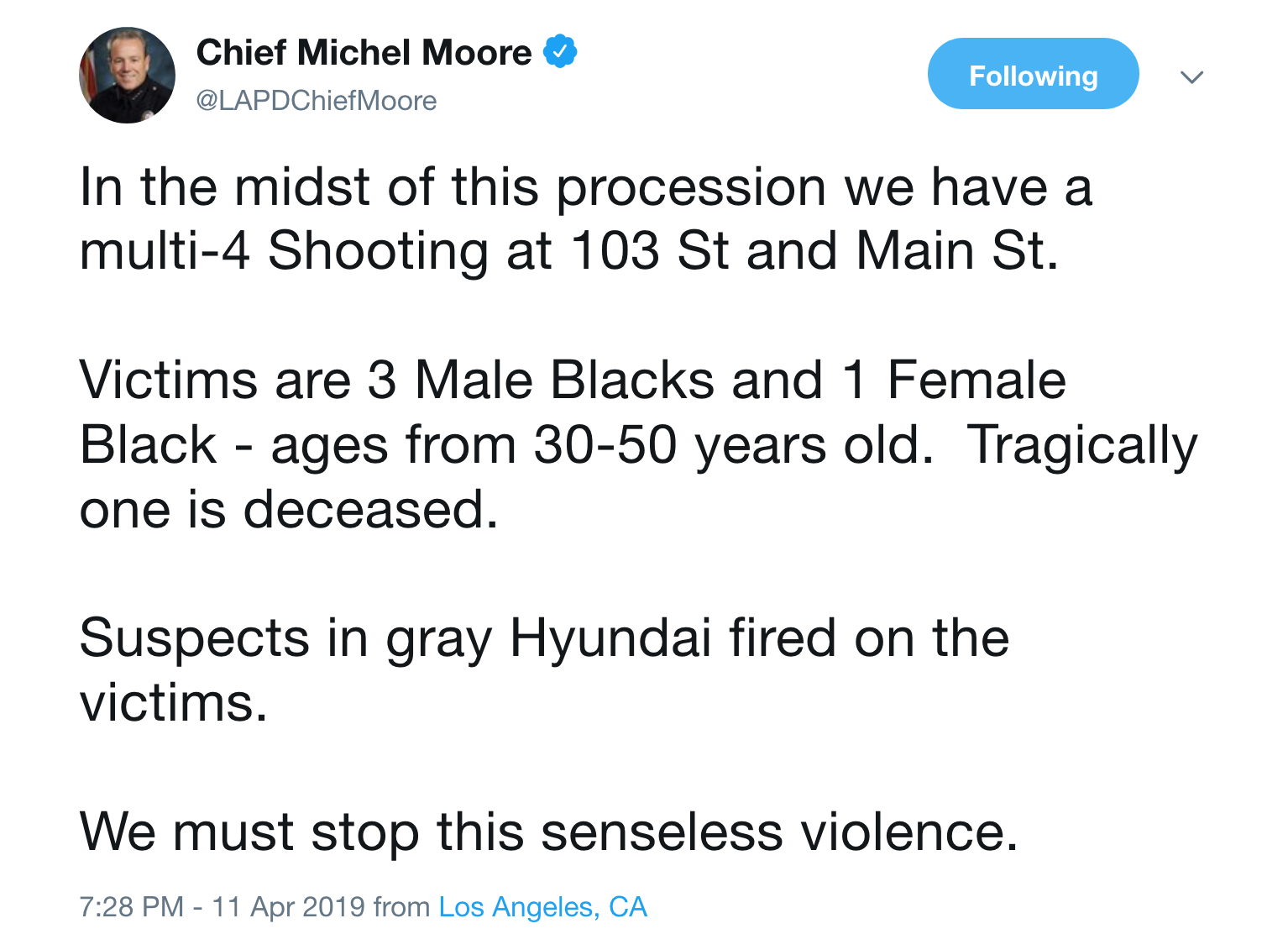

But if the LAPD had drawn more attention to Hussle's concerns about policing or their own contribution to building a nuisance case against his store, it would have been more difficult for Chief Michel Moore to weaponize him when tragedy struck.

Moore tied an unrelated shooting three hours after and several blocks away from where Hussle's funeral procession had passed through to the celebration of his life.

Things had been peaceful, reflective, and uplifting at Century and Main that afternoon (I left there around 4:30 p.m. - an hour and a half after his caravan had finished passing through). But most outlets again took the LAPD’s word as gospel, rarely stopping to check geography, the clock, or eyewitness accounts. ABC7 breathlessly reported someone had fired into the crowd of mourners along the procession route while a slew of headlines parroted the Chief’s tweet.

Although the L.A. Times would go on to report that the shooting was likely tied to recent incidents in Watts and wholly unconnected to the procession, the damage had been done. A tragic loss of life would forever be linked to Hussle's legacy.

Whatever window for reflection his passing cracked open at outlets that didn’t know who he was quickly slammed shut. Instead of recognizing the unprecedented level of unity across ‘hoods that his procession had facilitated, the question underlying too many of their reports had returned to the same problematic one 48 Hours had posed back in 1988:

"Why can’t you stop killing each other?"

_______

I swore to tell the world if I made it out/The truth about these L.A. streets and all what they about - Change Nothing

“If we living in hell, is it all right to sin?”

It's the kind of question Hussle preferred to ask, as he does in “Don’t Forget Us” (2013).

The question is rhetorical, of course. He was acutely aware that neither the rest of L.A. nor the rest of the country - which was deeply embroiled in debates about whether gangsta rap was destroying society just as his star was beginning to rise - was likely to listen to the conclusions he had come to.

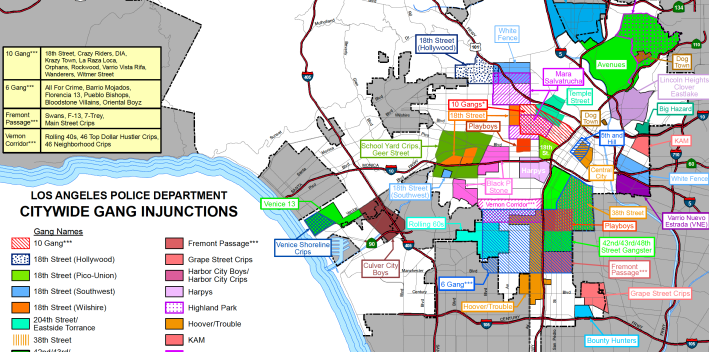

He’d been paying attention when the L.A. Times announced that the 60s had been served with a gang injunction by splashing the faces of nearly two dozen of his homies across the front page in 2003.

He understood all too well that reassuring the rest of the city that it was safe hinged on the LAPD making it appear like they were locking up the equivalent of Al Capone, as he put it in a 2009 interview with GINTV (below).

So he aimed his messages at the youth.

It had become urgent that he offer both inspiration and solutions to those ready to reconsider how they navigated the streets.

Three strikes laws, gang enhancements, and gang injunctions had essentially put targets on all of their backs in a new way, he explained (above). And the aggressive implementation of then-Chief William Bratton’s broken-windows approach to policing in 2002, coupled with the reconstitution of the gang units (they’d been disbanded after the 1998 Rampart scandal), meant the youth were under even more intense surveillance than usual.

“So if I come out rappin’ like Snoop and Dre...talking about palm trees and low-lows and house parties - that ain’t [our reality]," he said. "We can’t even have a party because police hopping out in paddy wagons, locking n*ggas up for associating with each other..."

He had almost gotten caught up in the raid of a 'hood day party himself in 2009. He'd been scheduled to perform at a Studio City venue the 60s had booked to get around the prohibition on association within their own neighborhood, but ended up not attending. Watching news of how 400 partygoers had been detained and searched for weapons (below), he pointed out that, being caught performing at an event attended by known gang members would not only have been a violation of his probation, the hysteria around the raid could have hurt his ability to perform at other venues. [One reporter even described the 60s as having used "secret" gang codes to set the party up.]

The grounds for the raid were rather shaky. Because the injunction against association did not apply outside the 60s’ neighborhood “safety zone,” they had a right to party in Studio City.

But LAPD didn't want them there.

"All these street gangs are criminal enterprises whose existence is based on violence," Chief Moore (then a Deputy Chief) told the Daily News. "And although they prey upon each other, sometimes this can spill over to innocent people in our neighborhoods."

So LAPD opted to try to catch known gang members on parole or probation in the act of associating with other known gang members by sending officers in "to gather information and look for wanted suspects," according to the LAPD's press release.

Beyond a "strong odor" of marijuana at the door (which the L.A. Times reported as the impetus for the raid), however, no weapons or drugs were ultimately reported found. The bulk of the two dozen arrests made were for parole/probation violations; four were arrested on outstanding warrants.

"I mean I guess they see it as...that's how they fight crime, that's how they fight the 'gang problem,'" said Hussle (below). "But... from everything I heard, it was a peaceful event."

People smoking weed wasn't a reason to bring out the SWAT team and the helicopters, he continued. "So a lot of the city's resources were devoted to somebody's personal agenda."

Crackdowns on parties were just the tip of the iceberg.

An eighteen-year-old girl Hussle knew had recently been given twelve years for throwing up gang signs during a fight. Normally, she would have done a year or two for assault, he told GINTV, but because she was seen on camera "banging the ‘hood," she got a gang enhancement (see interview at top of this section).

"Twelve years," he said.

“The crime you did, serious or not, [is looked at as if] you did it ‘for the benefit for your hood,’“ he said of how enhancements were being leveraged against youth. “So now you not being judged individually. It’s not your name...it’s ‘active affiliate and member of the Rollin' 60s, who’s responsible for countless amounts of murder, mayhem, and all type of other shit throughout the city.’ And that’s how they convict you in court.”

He wasn’t denying the 60s’ history or suggesting that they should be above the law.

As one of the largest and most powerful gangs in the country, the 60s had a well-documented history of committing major crimes, including bank robberies, carjackings, selling drugs, and taking gang-banging corporate. Members of the 60s had also been linked to dozens of murders in the early 2000s. Prior to the Karen Toshima killing, the 60s were most notorious for the horrific slaughter of the family of NFL player Kermit Alexander in 1984.

Hussle was also not denying that gang activity had done deep and lasting harm to the community.

On the contrary, in a number of other interviews recorded in 2009, he had used his affiliation and lyrical content as jumping off points to talk in depth about what it meant to grow up in what he described as the equivalent of a war zone.

“Imagine a person born in a country that’s been at war for twenty years and the war is fought outside your door… [not] on a base or a border,” he told Norwegian outlet 730.no (below, starting around the 3:20 mark). "It’s a different way that you come up. And it’s a different understanding of life that you exposed to when you involved in a gang or even live in an area that’s controlled by a gang.”

But he was saying that reducing people to their affiliation allowed police and the courts to claim almost any action contributed to some greater, more serious crime. Which, in turn, made it possible for them to lock youth away for “football numbers’” worth of time.

The injunctions also allowed for blanket criminalization and harassment of the entire community. Regardless of their affiliation, young men of color were now finding they couldn’t linger on a corner, be seen outside with more than one other person, wear white t-shirts, have anything resembling a gang tattoo, have a cellphone or pager, be caught tagging, use certain slang, or be in the vicinity of or even be caught waving to people they grew up next door to without getting hassled or arrested.

“It’s to the point where if me and my homeboys in the car and we driving through an area controlled by one of our enemy ‘hoods ...they’re going to automatically assume we here to kill someone and take us to jail for being out of what they call a ‘safe zone,’” Hussle told GINTV (at top of this section).

“So I can’t in my music tell n*ggas go get put on the hood and bang like we bang,“ he said, “...cause you ain’t gonna make it.”

_______

Had a vision that nobody else could see - Crenshaw and Slauson (True Story)

He had barely made it himself, even after "pioneer[ing] the transition from this Crippin'" and leaving active banging behind.

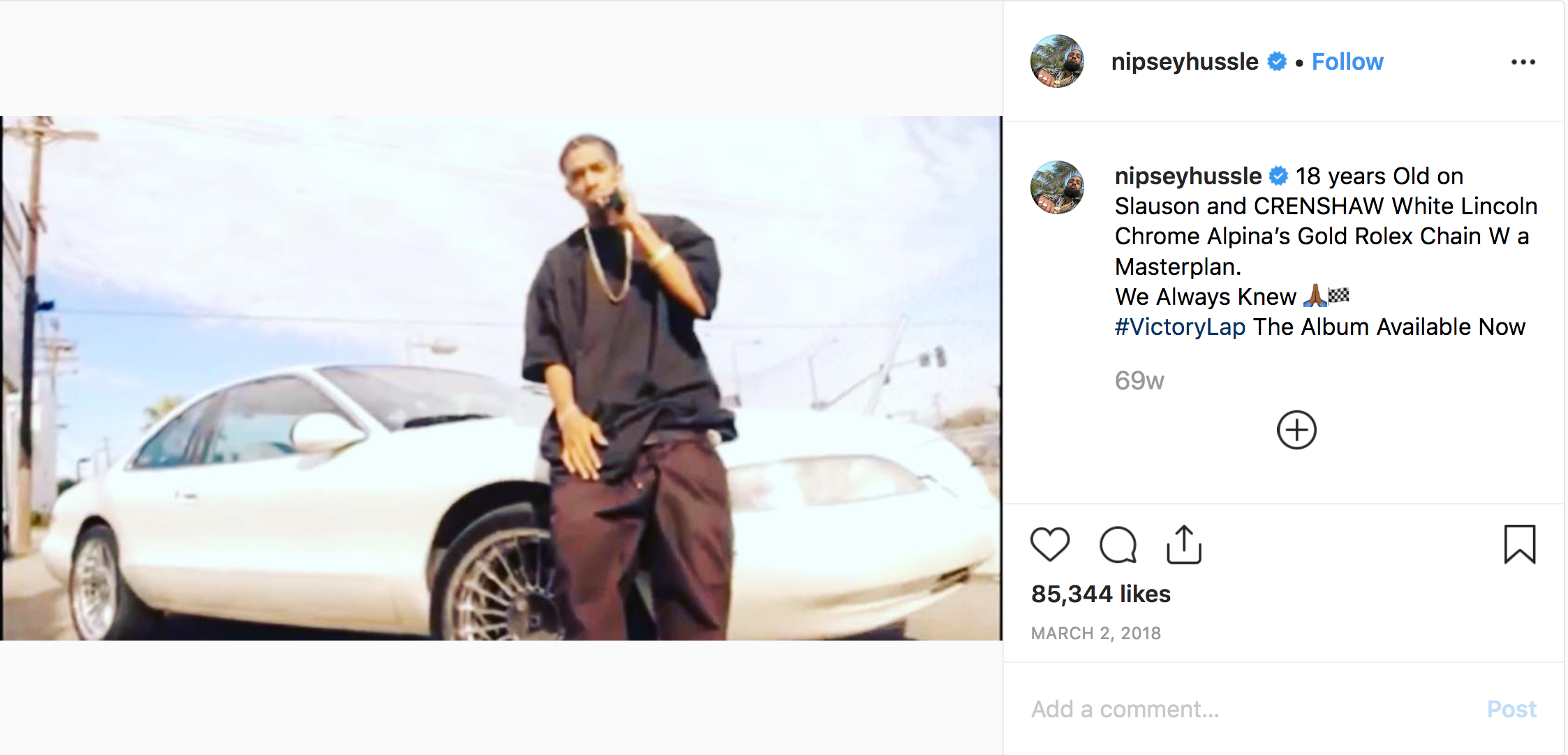

He was just eighteen (below) when he made the decision to sell his signature white Lincoln and sink the proceeds (and matching funds from Blacc Sam) into recording equipment.

He had grown tired of going back and forth between the recording studio and shootouts in the streets. But, he said (below), it had still been hard to give up the money he was making hustling. Not just because it left him broke and resorting to selling a few bucks’ worth of fake dope every now and then just to be able to stay in the studio. But having to give up all that cash, flash, and respect had been a blow to his ego.

Still, he knew that music had always been his first love - on that he had never wavered.

He had started writing at around nine years old. By age thirteen, he was taking the 108 to the Blue Line so he could take a music production class in Watts. And while he’d done well enough hustling his music at local businesses and in the parking lot at Crenshaw and Slauson, he realized that he would need to get out of the streets altogether if he wanted to take things to the next level.

So he holed up in the studio he’d built at Blacc Sam’s and got to work.

“I was really pure at that time,” he told Next Level Magazine last year of being completely focused on the music (below). “I wasn’t doing nothing but music.” [See the motivational messages they scrawled all over the walls of friend BH's bedroom/studio to keep themselves on track.]

But the LAPD had already decided who they thought he was. And they were loathe to change their minds about it.

So when officers came for Blacc Sam and raided the house, they used the gun found there to put a new case on Hussle, who was on probation for a gun charge at the time. It didn’t matter that it was registered, or that it wasn’t his, or that he purposely kept his distance from it. Officers also hauled away what he estimated to be well over $100,000 in studio equipment and jewelry, essentially leaving him with nothing.

“I was confused,” he said (above). “Where did the good karma pay off at? Where does this shit come back around at?”

Deeply demoralized and needing money for a lawyer, he stopped making music altogether and went back to hustling.

But even after producers encouraged him to get back into the studio and he got his career back on track with the 2008 release of Bullets Ain't Got No Name (Vol. 1), he would continue to be dogged by a police force that refused to see him as anything other than a threat.

He reported regular raids at their second store, Slauson Ave - launched in 2010 after Blacc Sam got home from jail (Slauson Tees, their first shop, had also been a casualty of the 2006 raid). It was all the more frustrating for the brothers because they had originally opened a shop in the plaza precisely because they had gotten tired of police confiscating the t-shirts they, and their late friend and business partner Stephen “Fatts” Donelson, had been vending on the sidewalk across the street.

Other run-ins had been dicier.

LAPD actually opened fire on Blacc Sam in the parking lot there in 2011 after arriving to break up what Eugene “Big U” Henley (Nipsey’s former manager) has characterized as a “family” dispute between himself and the brothers. [Blacc Sam had fired a gun into the air to safely break things up; officers responding to the scene claim Blacc Sam pointed a gun at them.]

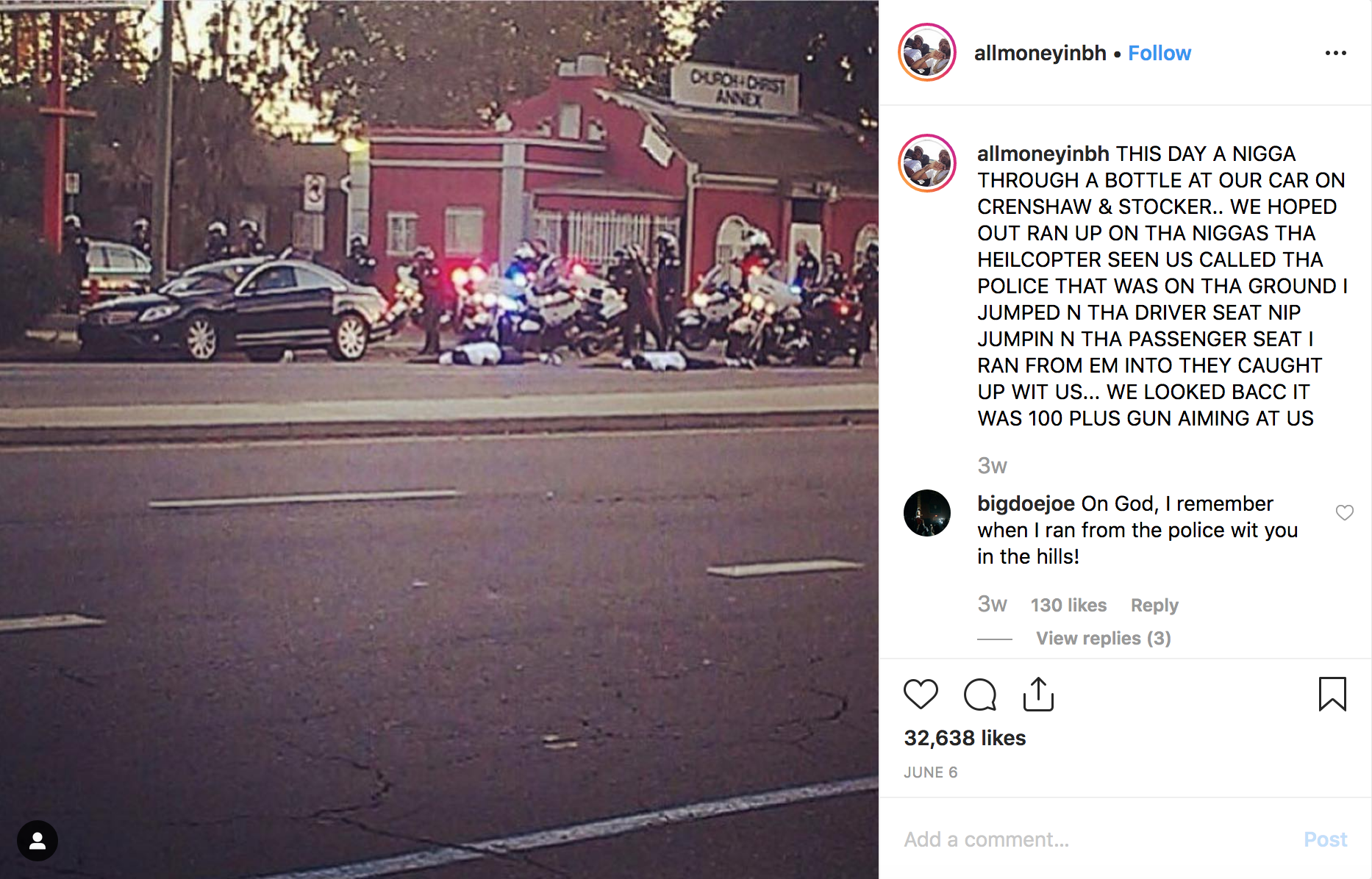

And in 2013, at the rally for Trayvon Martin in Leimert Park, an officer monitoring the gathering from one of several helicopters hovering above claimed they saw Hussle brandishing a gun. Neither Hussle nor BH had weapons - they had gotten out of their car to exchange words with someone who had thrown a bottle at them. But a jumpy LAPD - present that night in oppressively large numbers - chased Hussle and BH down and then had them lay spread-eagled on King Blvd. OnScene TV's footage of Hussle standing with officers on the side of the road shows they kept him cuffed for the duration of his detention, which ended up lasting a couple of hours.

Suspicion and hostility seemed to be the hallmark of every encounter he had with LAPD, whether officers were rushing up on him with weapons drawn and shoving him at the 2016 video shoot for "F*ck Donald Trump," arresting him for outstanding traffic violations after finding him parked in a disabled spot, towing the All Money In promotional truck from in front of the store (allegedly for having expired tags and being parked in a disabled spot) the day before Victory Lap dropped last year, or just finding random excuses to search his car and run warrant checks as he went to and from his store or the studio.

He tended to be philosophical about the harassment and often tried to turn it into a positive. When his truck was impounded, for example, he encouraged fans to take selfies in front of it and tag them with #FreetheBrinksTruck, saying he’d select one to win a prize.

“This corner is known for something else than what we doing [here],” Hussle said when asked about the intense scrutiny by Rap Radar hosts Elliott Wilson and Brian "B.Dot" Miller (below, at the 30 minute mark). “So it’s a transition and a learning curve that the police even going through to really accept that some people from over here are doing legitimate businesses and paying their taxes and doing everything by the book.”

It’s why he couldn’t take it “that personal,” he said. “Because they’re getting educated also...to who we are and what our real intentions are.”

But the fact that the city attorney had been pressuring their landlord to evict them from the building at the end of 2018, as Blacc Sam described in his moving eulogy (below, starting at about the 13:00 mark) and have continued that process since Hussle's passing, suggested neither the city nor law enforcement was ready to embrace that education.

And they were definitely not ready to acknowledge their role in creating and sustaining the conditions that Hussle and his All Money In team were trying so hard to help the community transcend.

Which meant they were likely blind to how poignantly Blacc Sam had captured the cumulative toll of disenfranchisement in his tearful confession (starting at 9:40) that, “For us to have something legit, something inspirational to attach ourselves to and not have to be doing something illegal… [was] something so special.”

_______

What was once gray skies is now white clouds/And I did it with the ones that y’all said was not the right crowd - Killer

“If you want to understand Black frustration,” Tafarai Bayne, Chief Strategist with CicLAvia, Transportation Commissioner, and Destination Crenshaw advisory council member, said this past April, “I give you Nipsey Hussle.”

Hussle had essentially done everything that would otherwise qualify him as a contributing member of society.

He had made it known from the outset that he did not condone violence and offered others a roadmap to follow. He had built bridges across ‘hoods and inspired others to do the same. And in the few short years he’d had the means, he’d done more to create opportunity for a community that had deliberately been denied it than most city agencies accomplished over the span of a generation.

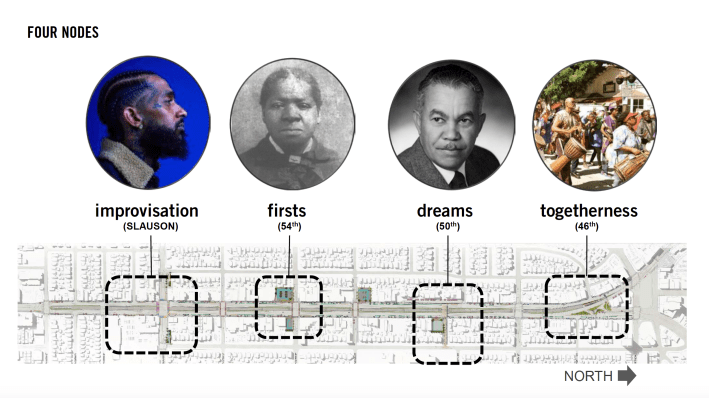

In an ideal world, the city would have viewed his acquisition of the lot at Crenshaw and Slauson as an opportunity to engage the otherwise hard-to-reach population of gang affiliates and folks re-entering the workforce Hussle had invested so much energy in bringing into the legal marketplace. They would have turned to the entrepreneurs Hussle and Gross created space for at Vector90 and asked how they might work together to address the needs of aspiring business owners and innovators in the community. Or they would have followed the lead of councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, whose championing of Hussle's inclusion as a thought leader for Destination Crenshaw had shown area youth - and particularly those who identified with Hussle’s experience - that their stories, ideas, and aspirations were vital to the future of the Crenshaw corridor.

Instead, Fox News personality, noted purveyor of bigotry, and infamous belittler of LeBron James, Laura Ingraham, had mocked Hussle’s death in a brief segment featuring images of rapper YG - who, incidentally could not look less like Hussle. The LAPD had continued to weaponize Hussle, arresting Kerry Lathan (shot in the back by Eric Holder that fateful day) for violating his parole by coming into contact with Hussle - a “known gang member” - when he visited The Marathon to buy a t-shirt. And the city attorney’s office had intensified its efforts to evict both Hussle and his legacy from Crenshaw and Slauson, while keeping the community and the councilmember wholly in the dark.

The hypocrisy was infuriating, a frustrated Bayne said of the impossible standards Hussle was being held to. Bayne, a native of South Central, had been excited about the possibility of working with Hussle and his Marathon store team on a future CicLAvia event planned for Crenshaw Boulevard.

“Why should any gangster even try?”

The official statement released by Blacc Sam yesterday points out that Black men coming into their power have historically been seen as a threat to the system and that “investigations, smear campaigns, espionage, and intimidation tactics” aimed at discrediting their voices have always come with the territory.

He and Hussle had expected the pushback, in other words. But Nipsey had also believed that “his purpose was to inspire those who had no inspiration…[to] show the people it can be done,” wrote Sam. So they had forged ahead.

Still, the investigation into The Marathon weighs heavily over the community.

Usually when it came to nuisance properties, Harris-Dawson said, neighbors initiated the case and the council office followed up or helped walk them through the process. Sometimes his office also filed complaints on behalf of neighbors. Neither had been the case here. His office hadn’t received a single complaint about the site. “Not one,” he said.

“Frankly, what we get the most complaints about in that intersection is Walsh/Shea [the firm that has been building the Crenshaw Line for the last five years],” said Harris-Dawson. “It isn’t any of the small businesses [there].”

Instead, it had been Hussle and Blacc Sam who had reached out to the council office for assistance with claims law enforcement had made against the store over the years. Despite the volume of claims they were dealing with, Harris-Dawson said, he’d never heard the brothers complain. And there hadn’t appeared to be any real urgency behind the claims until last fall.

It was not unprecedented for an investigation to be driven by the city attorney’s office this way, he said. But it was unusual. And the lack of transparency wasn’t helping.

“I think there’s missing information [regarding the impetus of the investigation], where all of this would make sense if we had that missing information,” he said.

Meanwhile, the illegal pot shops and liquor stores that have long attracted unhealthy activity or seen multiple people killed over the years continue to avoid the same level of scrutiny.

The lack of transparency around the investigation has also fueled speculation in the community and among Hussle’s fans regarding the city’s motives. With the Crenshaw Line scheduled to open in 2020, the NFL stadium taking shape in Inglewood, the (planned) replacement of Dorset Village with a massive luxury apartment complex, and the turnover the Crenshaw corridor is already experiencing, many have wondered if they’re witnessing a blatant land grab.

It’s not impossible, of course, but the truth may be more mundane.

The larger drive to deny the community a claim to place and space has manifested in a variety of ways in recent years, most notably in Metro’s resistance to including a stop along the Crenshaw Line at Leimert Park Village, the cultural beating heart of the Black community. [Although stakeholders would go on to win that battle, they lost the fight to block it from being run at-grade up the spine of the last Black business corridor in the city. Destination Crenshaw, the unapologetically Black open-air public art project planned to greet the train as it emerges from the ground near Slauson, is the community’s effort to turn that “insult into opportunity.”]

Until just last year, gang injunctions were another form of control, granting law enforcement significant power to limit who (mainly Black and brown youth and men) could access the public space across much of the city and how. Now effectively barred from enforcing those injunctions, the city may be looking to the abatement process to eliminate known or alleged gang gathering spots as a way to get around that.

And finally, while the tools at the LAPD’s disposal might change over time, it’s not clear that the attitudes toward the Black community, or the special resentment reserved for Black gang affiliates, ever truly will. LAPD gang enforcement training materials posted on MichaelKohlhaas.org suggest the LAPD saw the 1992 unrest not as a cry for justice, but as a turning point with regard to increasingly negative attitudes toward police officers. The Gang Impact Team curriculum (at least up through 2005) reiterated that Black gangs had “no respect for the police" and were prone to “planned attacks” on them (see page 14).

In the intervening years, the Black Lives Matter movement - also a response to the impunity with which Black people have been brutalized by police - has tended to be viewed as yet another attack on law enforcement. Flags with the thin blue line - adopted first as a rebuttal to Black Lives Matter (and later by white supremacists in Charlottesville) - have since become a more common sight around L.A. LAPD has openly carried them at events (with Mayor Eric Garcetti’s apparent blessing). Officers have put the symbol on their business cards. And on a wall in the Newton division in South L.A., the flag was unironically combined with Newton’s “Lucky 13” symbol to commemorate the police response to events rooted in a rejection of police brutality (see below).

In practice, that antagonism can manifest in the kind of contempt with which the Los Angeles Police Protective League (LAPPL) recently ripped into a 39-year-old man whose story had appeared in the L.A. Times’ coverage of the disproportionate stops of Black residents in South Central by the LAPD’s Metropolitan division. The Times described the man as a member of the Rollin’ 30s who had moved on from gang life and gotten a job as a youth counselor. The LAPPL post, which lashed out at the Times’ analysis more broadly, derided him as an “anonymous, just minding his own business, admitted active member of the entrenched violent street gang the Rollin’ 30s Harlem Crips,” before going on to mock his frustration over the stops he was regularly subjected to. It then admonished him for thinking he had the right to be left alone in his “high-crime” neighborhood, especially if he was going to do things like frequent a park controlled by the 30s.

As a gang member, the officers were essentially arguing, he had forfeited his right to place, if he had ever really had one.

Hussle’s refusal to renounce his ties to the 60s was, in many ways, an answer to the idea that law enforcement got to decide what it meant to be from his ‘hood or whether he had the right to be there.

Being from the 60s was part of his identity.

Claiming his ‘hood was a shorthand for his history - everything he’d endured, everything he’d survived, everything he’d been denied, everyone he’d lost, and everything he was about.

He couldn’t give it up.

But along the way, he’d also adapted it to fit who he had aspired to be, redefining being “from” somewhere to mean investing in your ‘hood, lifting up your people, being about family and community, betting on yourself, and never backing down from a fight.

It was that positive message - that call for collaborators from within gang culture from someone that was deeply rooted in the streets - that had resonated with so many of the young mourners seen lining the procession route. And with so many of the artists, thought leaders, and OGs that have kept the momentum for change going in the weeks and months since his passing.

The city may remain committed to dismantling Nipsey Hussle Tower before it ever achieves material form, but Hussle’s spirit pushes on.

“Crenshaw made me. So I’ll always be in Crenshaw. Always fighting,” he wrote in an essay for The Players’ Tribune last year. “The work ain’t done yet. The marathon continues.”

_______

Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman

Other coverage featuring Nipsey Hussle:

- February, 2019: Destination Crenshaw and the Rise of We-Built-this-Place-Making

- April, 2019: South Central Gives Nipsey Hussle the Send-Off of a Lifetime

- May, 2019: Billionaire Jeff Greene’s Plans to Raze Dorset Village Are About as Awful as You Might Imagine [Several of Nipsey's music videos were filmed here.]

- August, 2019: City Attorney Keeps up Pressure to Evict Nipsey Hussle’s Legacy from Crenshaw and Slauson

- September, 2019: L.A. Podcast Segment Begins Unpacking Nipsey Hussle’s Legacy with Chavonne Taylor, Tafarai Bayne, and Streetsblog L.A.’s Sahra Sulaiman

- November, 2019: Demolition of Dorset Village Planned for June of 2021

Notes

[1] Thirteen-year-old Devin Brown was killed by the LAPD after he led them on a brief chase in November of 2005. He had been driving erratically and, after a pursuit that lasted less than ten minutes, he crashed into a fence at 83rd and Western. Although Brown then backed the car up at a speed of approximately two miles per hour and Officer Steve Garcia was not in the path of the vehicle, Garcia claimed he feared for his life and fired ten shots into the car, striking Brown seven times and killing him. An internal investigation by the LAPD would find the shooting to be within policy. The finding contrasted with that of the Police Commission, but information about how the LAPD panel had come to that conclusion was unavailable. The year before, the California Supreme Court had ruled police personnel documents were not public records, allowing the LAPD to close disciplinary hearings to the public. See more on the story here.

[2] This is a highly condensed timeline. The history of gangs is obviously far more complicated than can fit here. Each gang has its own story, and the different generations within each gang all have their own stories, as well. The key point, as noted, is that they cannot be considered in isolation from the structural conditions that they are a response to. Visit Alex Alonso’s Street TV channel to see a wide range of oral histories or see an early work of Alonso's on the formation of Black gangs.

Sahra is Communities Editor for Streetsblog L.A., covering the intersection of mobility with race, class, history, representation, policing, housing, health, culture, community, and access to the public space in Boyle Heights and South Central Los Angeles.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Los Angeles

LAPD Was Crossing Against Red Light in Crash that Killed Pedestrian and Injured Six in Hollywood

The department says the officers had turned on their lights and sirens just before crossing. Their reasons for doing so remain unknown.

Freeway Drivers Keep Slamming into Bridge Railing in Griffith Park

Drivers keep smashing the Riverside Drive Bridge railing - plus a few other Griffith Park bike/walk updates