Staff from the Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) had already packed up their Vision Zero maps and materials and headed out the back of the Mark Ridley-Thomas Constituent Service Center by the time the "Justice for Woon" rally attendees arrived last Thursday evening.

The rallygoers - members of the Chief Lunes crew and friends and family of cyclist Frederick "Woon" Frazier who was killed this past April in a horrific hit-and-run - had started out their night by holding a press conference at the place where Woon had been hit.

The Manchester/Normandie site was only a half-mile away from the constituent center at Vermont/Manchester, but the distance between the parties felt like it ran much deeper than that.

The original intent of the rally had been for Woon's family and friends to be able to express their anger at how slowly the wheels of justice were turning.

They didn't understand why 23-year-old Mariah Banks remained free on bail after having confessed to running Woon down, leaving the scene, driving 75 miles east to Moreno Valley, and trying to hide the vehicle by painting it black. And they didn't understand why her first appearance in court this past June 8 had failed to result in formal charges.

By rallying at the site where Woon had been hit, they hoped to both shame the district attorney into taking such cases more seriously and remind city officials that they could do their part to protect youth like Woon by putting a protected bike lane in along Manchester.

But some of the very people they hoped would be paying attention - including the area's councilmember and the head of LADOT - were half a mile away at the constituent center, talking with residents about the importance of left-turn pockets.

That meeting, called by the office of councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson with the support of LADOT, was in response to the rash of crashes that have claimed the lives of 19 pedestrians and cyclists in South L.A. since January.

Yet the boards set up around the room suggested LADOT had significantly scaled back many of the "phase one" Vision Zero fixes it had mapped out for residents at outreach meetings last summer. Instead, both in Seleta Reynolds' remarks and on the boards themselves, LADOT was downplaying speed as a factor in crashes and playing up the benefits a handful of non-controversial left-turn pockets at a few key intersections could make.

Perhaps more troubling still, the backlash over westside road diets that spawned a half-hearted recall attempt of councilmember Mike Bonin had sapped the little appetite the agency and other elected officials had for championing major street reconfigurations. Meaning bolder things like the road diet proposed for Hoover and other key corridors are on indefinite hold, if they haven't been scrapped altogether.

It wouldn't be the first time shenanigans in wealthier neighborhoods hurt the ability of under-resourced communities to get what they needed. But it's especially heartbreaking given the fact that there is now some real momentum behind the push for safer passage for cyclists and pedestrians.

Although the visibility of fatal crashes has improved over the years, few things managed to jolt Angelenos awake like the live capture of a woman intentionally plowing into cyclists mourning Woon's loss at Manchester and Normandie this past April.

Seeing the driver gun her engine and send Quatrell Stallings flying brought home for viewers how fragile the human body could be when slammed into by a speeding vehicle. Suddenly, reporters were asking LAPD officers about their stance on bike lanes at press events and why we didn't have more of them. When Woon's friends organized a rally and ride a few days later, news helicopters tracked the ride for hours and broadcast the youths' heartfelt pleas that their safety be taken seriously and that Woon's killer be brought to justice. Even the New York Times picked up the story recently, asking if the youths' basic but sustained demand for safe passage could finally begin to turn the tide in L.A.'s car culture.

Given all that, it was odd that the councilmember's office had not only not reached out to the rally organizers to get a grassroots support boost, but had moved their own event (itself an event that had only been announced two days earlier) from Wednesday night to Thursday night, essentially pitting it against the rally.

While the intention of the councilmember's office may, as was communicated, have been to draw attention to the issue of pedestrian safety, especially in light of June crashes along Florence that claimed the lives of teen Gabby Leyva and an elderly woman, to Woon's friends and family, it felt deeply disrespectful.

So when the rallygoers arrived around 7:30 p.m. with the press in tow, Woon's mother, Beverly Owens Addison, aimed to make maximum impact. She spoke about her son's final, horrifying moments: the force with which he had hit the ground and how it had broken every bone in his face; his broken back; his shattered legs; the extensive internal bleeding. All she had left to hold of her only son, she said, was his ashes.

"Somebody needs to be held accountable for [killing] my child - my only child!" she implored.

Their agitation over feeling ignored grew when a councilmember's staffer offered to bring Owens Addison inside to meet with Harris-Dawson, where he was in the middle of another meeting.

Viewing it as an attempt to get out of answering to the community, Owens Addison refused.

This was not the case - there was little the councilmember could say with regard to how Banks prosecution was unfolding. Unfortunately, history has shown that our legal framing of hit-and-runs as tragic and unintentional "accidents" makes it harder to exact the justice families seek.

Readers may remember the 2013 hit-and-run that killed Luis "Andy" Garcia and left two other cyclists lying injured in the street. Not only did drunk driver Wendy Villegas remain out on bail for months, her lawyer complained to the judge in front of the family that an ankle monitor clashed with her shoes and unfairly hampered her lifestyle as a college student. Garcia's family was also kept in the dark regarding the plea deal attorneys cut behind their back that reduced a possible 15-year sentence to 3 years and 8 months (of which Villegas would eventually serve only about 18 months). And they had to suffer through the judge's bizarre attempt to admonish Villegas, in which the stone-faced young woman was told that the next time she drove drunk and killed someone, she would be charged with murder.

Still, the failure to make an accommodation for a grieving mother on a night that was supposed to be about preventing incidents like the one that took Woon's life did not make much sense to the large group that was now milling outside the constituent center.

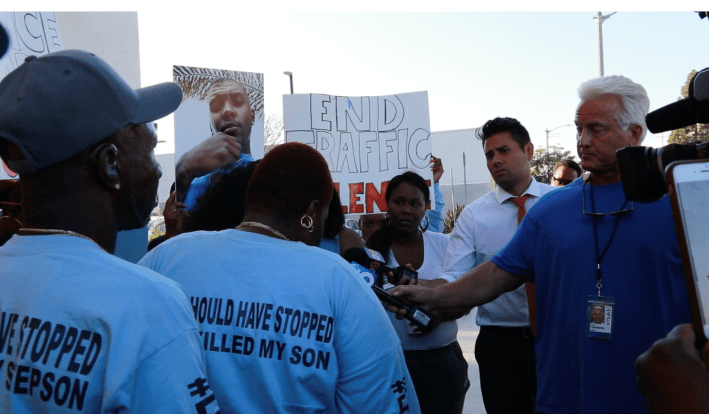

So when Harris-Dawson emerged to meet with the group a few minutes later, he was immediately surrounded.

Harris-Dawson told the cyclists that, given that there were more pedestrian and cyclist fatalities in the district, he was looking both to see more money allocated to his district and to have more people hired so that the fixes could be implemented more quickly.

As he talked, a frustrated Owens Addison - fed up with waiting for the councilmember to stop and speak to her for a moment - announced that what she was hearing was "straight bullshit" before finally walking away.

Undaunted, cyclist Spencer Sims of the Woon Justice for South L.A. coalition continued to pepper Harris-Dawson with questions, asking about the possibility of a protected bike lane along Manchester (something that is eventually supposed to be built, according to the Mobility Plan 2035).

Harris-Dawson said he hadn't seen a proposal for such a project yet but that he tended to be on the side of bike lanes. He just wanted to ensure that if such a lane were going to be planned for the area, that there was a real conversation with area block clubs, neighborhood councils, and community members about it first.

In a community that has long been denied infrastructure, had it imposed upon them in harmful ways, or seen the arrival of infrastructure that appeared to be meant to serve newer, better-off residents, that conversation must be had.

A protected lane might have significant benefits, he said, but that needs to be communicated to stakeholders (especially seniors) so they understand that to be the case, too.

"We would have loved to have you all" at the meeting they had just held, Harris-Dawson offered.

"We heard this was last-minute...?" ventured Edin Barrientos, Chief Lunes founder and another key organizer with Woon Justice for South L.A.

It was, acknowledged Harris-Dawson. But it was the first in a series the office would be holding, he said. They would be sure let everyone know about the next one as soon as the date was set.

As he finished up his remarks, a rallygoer interrupted to announce the group was heading back to the crash site to finish out their press conference. They weren't done mourning.

Back at the site, standing around a life-sized photo of Woon, they lamented being made to feel like a burden for wanting justice for their loved one.

"We just don't understand...why can't she be held accountable?" asked Danita Lashay.

"This person right here meant something to us. He meant something to a lot of these people out here," she said. "And we all want to know: Why?"

For more on Woon's case, see our previous coverage below.

- June 7, 2018: LAPD Announces Arrests in Hit-and-Runs that Killed Frederick Frazier and Injured Quatrell Stallings

- May 15, 2018: Hit-and-Run Driver that Killed Frederick “Woon” Frazier Turns Herself in; Details Still Emerging

- April 18, 2018: Security Footage Shows Moments Before Frederick “Woon” Frazier Hit from Behind; Police Still Seeking Leads

- April 16, 2018: “The Car Culture that We Have Is Not Promoting Life:” Riders Gather to Remember Frederick “Woon” Frazier

- April 11, 2018: 22-year-old Killed in Hit-and-Run at Manchester/Normandie; Driver Plows Through Mourners Corking Intersection to Protest Death