Correction: The initial version of this story cited the rookie officer as the one driving the patrol vehicle during the pursuit. Further review of the LAPD's briefing video suggests the senior officer was the one driving during the pursuit. We regret the error.

During the discussion of the high incidence of bystander harm from pursuits at the April 25, 2023, Police Commission meeting, LAPD Deputy Chief Donald Graham and then-Chief Michel Moore reassured commissioners that department policy prioritized the “balance test” – a weighing of the seriousness of the violations against the potential risks to officers or the public – to determine whether a pursuit should be initiated, continued, and/or abandoned.

To that end, Graham said, officers are trained to constantly monitor their surroundings – weather, roadway, neighborhood, and traffic conditions, the presence of pedestrians and cyclists, the relative speed of the pursuit, etc. – and factor it into their decision making. They are also reminded to ask themselves key questions – "'Do we have a license plate?' 'Do we have a known suspect?' and 'Can we catch this person at another time?'" – to help reduce pursuit footprints in communities. The extent to which the “balance test” is reinforced in roll call and in the evaluation of pursuit outcomes marks a tangible shift from past practice, he said.

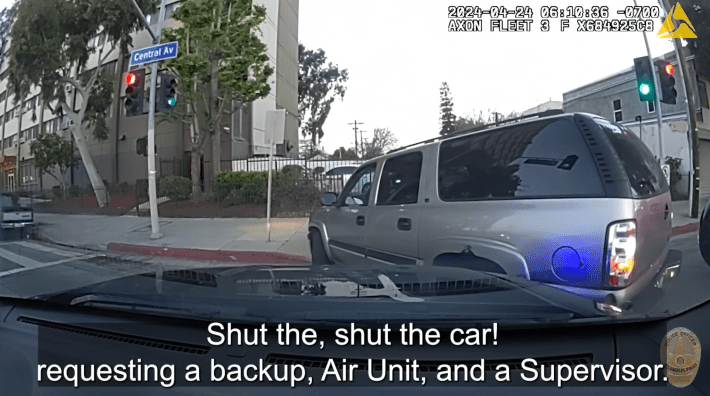

But dash cam audio from a catastrophic pursuit that took place April 24 – almost a year to the day after Graham's presentation – suggests not everyone is on board with that approach.

The officers never reference public safety, the surrounding conditions, or whether the suspect can be picked up later.

They also don't reference the violation except to make a mid-pursuit request for confirmation that a crime had been committed.

Instead, the running dialog between what appears to be a probationary officer and the field training officer he's been paired with – the very person who should be instilling the significance of the "balance test" in a probie – is laser-focused on radio protocol.

And suspect apprehension.

Right up through the moment that that alleged suspect (later identified as 23-year-old Germaine Smith) plows through 46-year-old cyclist José David Monsalve Rojas at ~60 mph while flying the wrong way up a busy narrow street.

__________

The brief but harrowing pursuit began just after 6 a.m., when officers attempted to approach an alleged theft suspect – Smith – at 48th and Central.

They had been alerted to his location by the victim, who had tracked him via the electronic device she said was stolen from her vehicle the night before.

In her initial 911 call that morning, she provided LAPD with a description of Smith and the vehicle he was driving, including the license plate, and then continued to update dispatchers block by block as she tailed him from Broadway and Gage toward Central-Alameda.

LAPD did not respond to Streetsblog’s queries about the officers’ ranks and status, but the rookie officer’s greenness is immediately apparent. As they approach the intersection where Smith’s SUV can be seen idling in the driveway, he asks if they should run the light.

The partner officer counsels him to check the license plate first. They move through the red light when it is confirmed to be the vehicle they are searching for.

As they run the red, the partner officer peppers the rookie with more instructions: call in a Code Six (field investigation); request backup, an airship, and a supervisor.

The rookie does so as they park behind Smith. But Smith takes advantage of the gap between the vehicles and flees southbound on Central.

As the officers hop back in the vehicle, the senior officer appears to be behind the wheel and assuming responsibility for the pursuit.

Per LAPD policy, this is also the moment he should have performed a balance test. If he was indeed a training officer, it also would have been the ideal time to walk his trainee through the assessment of whether a pursuit was actually warranted.

Those first moments are so crucial.

LAPD's own data shows its briefest pursuits tend to be the most dangerous. Between 2018 and early 2023, nearly half of the crashes resulting in serious injury or death occurred within the first sixty seconds of a formal chase.

That doesn't leave a lot of time for decision-making. But in this particular case, the questions Graham had highlighted for the Police Commission may not have been that hard to answer: they had Smith's license plate and he appears to have been trackable via an electronic device.

More importantly, the initial violation – a theft from a vehicle – was nonviolent and not an automatic felony.

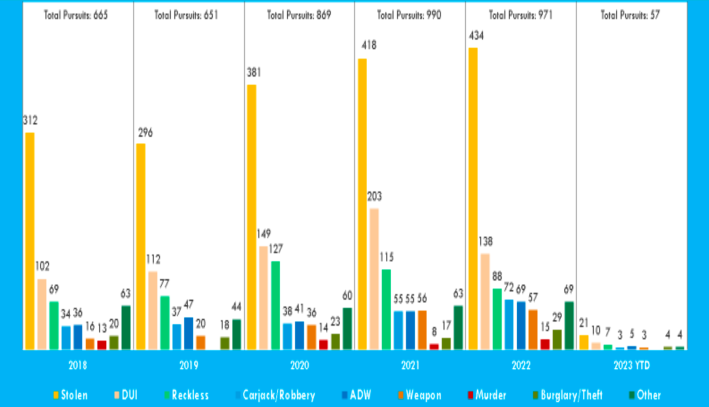

Department policy allows officers to initiate pursuits in response to suspected felonies and, more controversially, misdemeanor offenses like drunk or reckless driving. Chases involving a stolen or perceived stolen vehicle comprise the greatest share of pursuits (44 percent). Those involving a burglary – of which a theft from a vehicle would be an even smaller subset – are far more rare.

But the question of whether pursuit initiation is appropriate never comes up. The senior officer focuses on radio protocol instead.

"Put it out," he says, reminding the rookie to advise dispatch they are initiating. The rookie obeys, but forgets to provide details. "Tell 'em where we're going," the senior officer says. "Direction."

As the rookie complies, Smith hangs a hard left onto 52nd. He accelerates as he squeezes his way between two vehicles on a residential street.

It is a prime opportunity to consider Smith’s recklessness and the threat it could pose to public safety. But the senior officer is otherwise preoccupied.

"Have a unit meet with the victim to verify we have a crime," he advises. The rookie calls in the request.

Meanwhile, Smith careens northbound onto Hooper and shoots up the middle of the street at high speed. Disaster now feels inevitable.

Hooper is an older street that is home to a mix of residential and commercial uses and which is just wide enough to accommodate parking on both sides but also narrow enough that there isn’t a lot of extra room to maneuver. It is an essential conduit for commuters heading toward downtown, and northbound traffic stacks up early.

Yet, as Smith continues to drive on the yellow line and force oncoming traffic toward the curb, the senior officer appears locked into protocol, dictating instructions for yet more backup. He tells the rookie to request four additional units because of other occupants* in the vehicle. [*Initial reports alluded to other occupants in the vehicle, but they are not seen or discussed in the briefing video or in any local TV reports/footage from that morning. LAPD has not responded to a request for confirmation other occupants were indeed present.]

At 48th, Smith fully crosses into the opposite lane to get around a bus. He never crosses back.

A security camera at 47th catches him streaking past northbound traffic on the wrong side of the street. He is moving so fast that a man working on his car didn't even see him until Smith whooshed by him, missing him by just inches (see the near-miss in KTLA's report).

As the officers pass the man Smith nearly hit (below), the dispatcher relays the request for backup.

Then one of the officers lets out what sounds like a muffled expletive.

Smith has hit Monsalve Rojas at 46th, lost control of his vehicle, and crashed violently.

"Tell them [the suspect] crashed," the senior officer urges, interrupting the rookie's Code Six broadcast. "Tell them he TC'd."

__________

"TC" or "traffic collision" doesn't quite capture the horror of what has happened.

The pursuit traveled just under a mile and lasted just over a minute. Factoring in his acceleration up Hooper, Smith was likely traveling at or above 60 mph when he collided with Monsalve Rojas.

The violence of the impact knocked the father of five out of his shoes and sent him crashing into the top of a car parked 75 feet away. Per what a traumatized witness told Primer Impacto, the edge of the car's roof tore Monsalve Rojas into pieces.

Smith subsequently lost control of the SUV and pinballed his way between more than half a dozen parked and northbound vehicles for a full block before knocking a telephone pole into a front yard and coming to rest upside down in the middle of the lane.

It is difficult to square the trail of death and destruction with the “evidence” recovered at the scene.

Although LAPD describes the grab-bag of trash below as "containing cash, an electronic device, and several identification cards belonging to different people," just one California ID appears to be visible. The department would not clarify whether the stolen “electronic device” was a tracking device or an actual personal item of value.

Smith initially survived the crash and made a very brief and very shaky run for it. The 23-year-old was taken to the hospital after complaining of back pain, became ill as he was being processed for release, and died five days later, compounding the tragedy.

__________

Back in 2016, LAPD told the L.A. Times it had begun revising its pursuit policy in 2015 to better address public safety.

The revisions were said to be "routine." But 2015 was also the year reporter James Queally's investigation found LAPD pursuits injured bystanders “at more than twice the rate of police chases in the rest of California" – one for every ten pursuits between 2006 and 2014. By the end of 2015, things were even more dire: the department had logged 78 bystander injuries – the highest number in a decade.

Although LAPD does not count it as such, that year also saw a gruesome pursuit-related death: the decapitation of a 15-year-old boy by a driver fleeing police at 90 mph in a stolen vehicle.

LAPD claimed the officers weren’t technically engaged in a pursuit at the time because they hadn’t tried to stop the vehicle or turned on their emergency lights/sirens. But the Grand Jury that took up police pursuits and public safety in 2017 saw it differently. They used that case and the Times’ data to call for both LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department to concern themselves with pursuit outcomes – particularly associated injuries – and adopt policies and practices that would reduce civilian casualties as well as property damage.

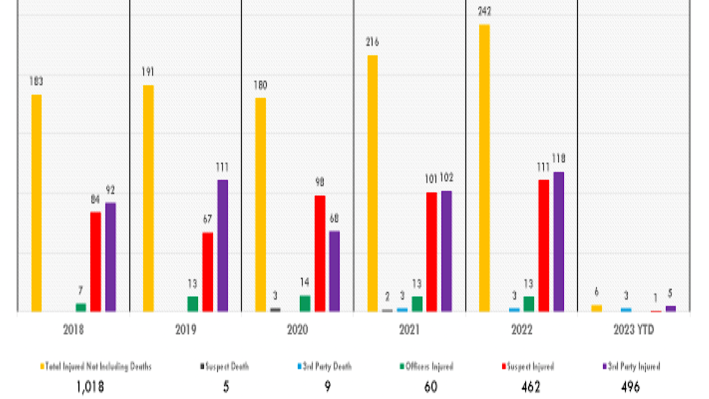

On paper, LAPD policy does now reflect those priorities. But even with those changes, pursuits remain a significant threat to public safety. Of the 4,203 pursuits between 2018 and early 2023, a quarter – 1,032 pursuits – led to collisions causing injury or death. Bystanders accounted for just under half of those casualties.

pursuits, 1,032 resulted in a collision with injury or death. 496 bystanders were injured; nine bystanders died. 462 pursuit subjects were injured; five died. 60 officers were injured. Graph: LAPD presentation to the Police Commission on pursuits

All of which raises questions about how learning and change take place within the department. And whether the way pursuit data is currently categorized reflects the true picture of how chases are conducted on our city streets.

LAPD has tended to be more transparent about pursuit decision-making when officers have followed policy to the letter and navigated difficult circumstances well. Earlier this year, when a 16-year-old girl was killed in a fiery solo crash in Encino, the department did not hesitate to tell the media police had initially attempted to conduct a traffic stop on the vehicle but opted not to pursue when it sped off in the rain. The briefing video released a month later was similarly transparent, detailing the senior officer's reasoning and making clear the officers had abandoned the pursuit a full minute before the speeding teens crashed into a pole.

There was no such transparency with the horrific crash that killed Janisha Harris and Jamarae Keyes at Broadway and Manchester in 2022.

Instead of acknowledging officers had been chasing the Cadillac that hit Harris and Keyes when it blew through the red light at Broadway at nearly 70 mph, LAPD was adamant that "this was never a pursuit." Officers had only been trying to effect a traffic stop after noticing the driver – later identified as Matthew Sutton – speeding on Manchester, they said.

LAPD had to walk back those statements back a few days later, after the victims' families saw the engagement referred to as a pursuit in the police report. But the department insisted the pursuit had been brief – lasting about 15 seconds – and that officers had terminated it before Sutton reached Broadway.

Dash cam footage released a week later suggested that was not exactly true, either.

Officers Edwin Villalpando and Kevin Santizo had actually begun the chase a full minute earlier, after allegedly spotting Sutton speeding on San Pedro. The briefing video suggests the justification was Sutton’s "numerous traffic violations." But LAPD's own footage shows Sutton committed the majority of those infractions while trying to evade the officers, who aggressively blew through two red lights prior to flipping on their lights/sirens. [The officers did flash their lights and chirp at Sutton a couple of times as they followed him through side streets, but they did not flip the lights/sirens on in a sustained way until just after turning onto Manchester... after the officers nearly collided with an oncoming vehicle while running the second red light.]

While it is true the officers shut their lights/sirens off two seconds before Sutton slammed into Harris and Keyes (below), a full explanation for why they did so has not yet been offered.

LAPD describes it as the termination of a pursuit.

But the officers had never called one in to begin with. They didn’t have sufficient justification to initiate.

Instead, the likely goal of the unofficial chase had been to find sufficient justification for a pretextual stop.

To conduct a pretextual stop, officers have must "articulable information in addition to the traffic violation... regarding a serious crime (i.e. a crime with potential for great bodily injury or death)," per the policy LAPD adopted in 2022.

A speeding violation isn't enough. But a speeding driver who is also seen behaving recklessly – as Sutton was once Villalpando and Santizo began chasing him – could technically be a candidate for a fishing expedition.

The danger is that that candidate, likely hyper-aware of why they are being tailed, hits the gas, as Sutton did when the officers finally attempted to pull him over.

To follow him as he accelerated to nearly 70 mph, the officers would have had to alert dispatch, formally initiate a pursuit, and account for their decisions. Meaning it is possible they backed off to avoid all that.

Either way, they do not appear to have been eager to broadcast their role in the collision. Dispatch is not immediately notified of the crash. And radio chatter captured on a citizen scanner suggests it was ascribed to the driver being under the influence.

__________

Whether catastrophic outcomes like these have compelled the department to look at how officers push the boundaries of its stop and pursuit policies is unknown. What is known is that the department's approach to information sharing discourages the public from asking such questions.

LAPD generally does not post incident statements on pursuits or release critical incident briefings unless there is an officer-involved shooting or a public outcry for more information. When briefings are produced, they tend to provide the bare minimum of information, feature selective editing and misdirection, and favor exonerative framing.

Take the recent case of an unofficial pursuit in Hollywood that killed one person and sent six others to the hospital. The crash occurred when officers – who were following someone they appear to have been seeking justification to conduct a pretextual stop on, per the department's statement to L.A. TACO – were hit while crossing against the red light and spun around into a pedestrian in the crosswalk.

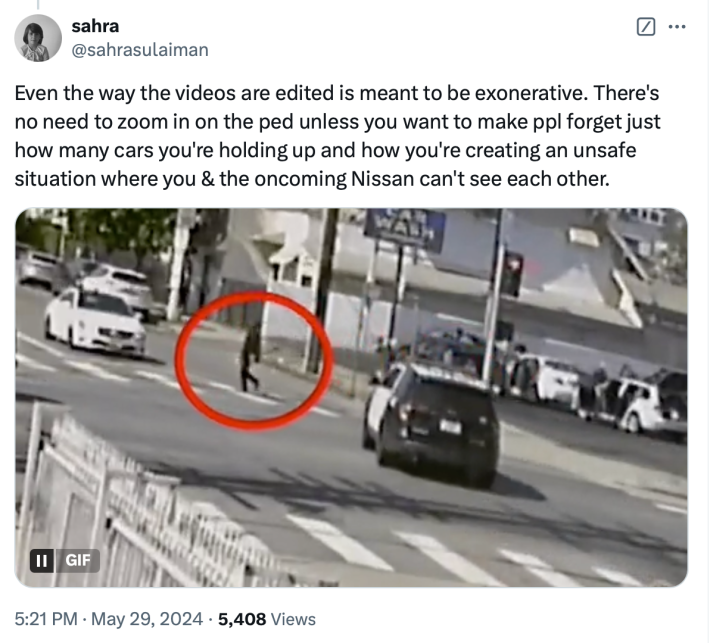

The department's briefing video provides a very brief snippet of dash cam footage as well as two different angles of the intersection at Hollywood/Gower, as captured by area security cams.

Instead of just letting the security footage roll, however, LAPD zooms in on the pedestrian, narrowing the view of Hollywood Boulevard, cropping out traffic, and hiding just how difficult it would have been for the driver of the silver Nissan to see the cruiser (and vice versa) as it approached the far lane.

They employ the same technique in the second clip (below), cutting the patrol vehicle completely out of frame until just before it is struck.

The effect is to focus the viewer on the pedestrian’s terrible fate and away from the fact that the officers had turned off their lights/sirens midway through the crossing – a key detail the LAPD omits from its description of events.

In doing so, LAPD opens up the possibility – at least, in the mind of the viewer – that the driver of the Nissan bears some of the blame.

A similar approach can be seen in the briefing for the April 24 pursuit that killed Monsalve Rojas. The department treats the public to two different angles of Smith's collision with the cyclist and then a third gratuitously enhanced view of the collision in slow motion.

The gruesomeness serves zero informational purpose. But the clips do succeed in reminding the viewer of Smith's recklessness while avoiding discussion of the senior officer's failure to recognize it.

Local coverage of the incident generally followed the department's lead, focusing on Smith's actions, the tragic loss of a father of five who was on his way to work, how dangerous Hooper Avenue can be, and how dangerous pursuits can be, more generally. Even this reporter had to watch the briefing video half a dozen times before catching onto the relationship between the senior officer and the rookie he was mentoring.

Ultimately, it's public safety that suffers for it.

As Deputy Chief Graham himself noted in his remarks to the Police Commission last year, driving "3000-pound bullets" at high speeds is "the most dangerous thing" the department does. But it's difficult to have a robust public conversation around pursuits – official or otherwise – when the department continues to work so hard to shield them from scrutiny.

__________

A gofundme for the family of José Monsalve Rojas has been set up by his niece, Valentina Pérez.