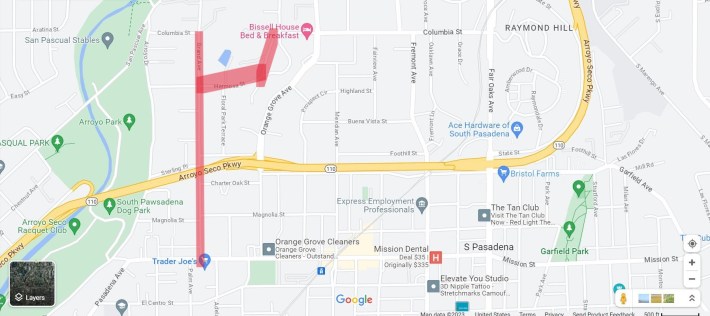

South Pasadenans have had since last September to adapt and respond to a series of quick-build multimodal road facilities, along Grand Avenue and also Oak Street. These include bike lanes, curb extensions, high-visibility crosswalks, and Slow Streets signs.

According to city staff, no speed or collision data was collected prior to the demonstration program, which was only meant to run for six months starting in late August 2023.

The installations were funded by a $420,000 Metro grant from 2019 for Open Streets events. Then in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic came, and the money was repurposed. In 2022, the San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments gave the city another $45k to get something done with the funding before its November 2023 usage deadline. This is it.

At this point, it’s been more than six months, and residents have formed opinions. On March 20th city council voted to do away with most of the bike lanes and all of the delineators, under pressure from locals who didn’t want them in their neighborhoods. Some neighbors allegedly even ran materials over.

Transportation Commissioner Diego Zavala told the council he’s been maintaining the project since August 2023.

“I've had at least three instances – seemingly intentional – of damaging; such as swerving into the cones to run them over while I was working on the streets.” Zavala said. “This is an indication that more permanent solutions will erase any opportunity for erratic drivers to harm pedestrians in these areas.”

Why such resentment towards pieces of plastic?

Grand Avenue resident Mark Dreskin said he didn’t know there were going to be installations until he woke up one morning and found them already in the ground.

“Really, no preparation at all.” is how Dreskin described project outreach. “And the thing that we're used to is they do filming on the street, they come along and they lay these flyers and they say, ‘We'll be filming tomorrow.’ Whatever happened to let the residents know that this [was happening] was not visible to me at all.”

Dreskin said there was a right way to do this, to get opinions before installation, but he doesn’t believe resident input was given enough value. There was a consistent theme at the meeting of attributing the project to influence from outsiders and cycling groups.

“Input from people outside of our street where we live is important,” said Dreskin, “but I also don't want to give instructions on what should happen in front of other people's houses.”

Earlier in the meeting, South Pasadena’s Transportation Program Manager David Peña had gone over the outreach background for the quick-build project. He said a subconsultant had done door to door canvassing in 2021 and dropped off fliers in July 2023, about a month before the project was installed.

Peña went on to elaborate on the feedback the city has received since then.

“So the majority of residents who live on Grand Avenue are not in favor of keeping the bike lane on Grand Avenue.” Peña stated. “However, there is support for the bike lane from some residents who live on Grand, other areas in the city, bike organizations, and other members of the public who have come out in support of maintaining the bike lane.”

One such local was Mike Segal, who implored the council to look at regional connectivity.

“Our neighbors in Pasadena over the next three years are building a lot of multimodal projects that come into South Pasadena. Alhambra just last week passed the same, a lot of projects that are multimodal coming into South Pasadena. And we need to build out our network. Yes, it's only three blocks, but it's the first of many to build a network.” said Segal.

“We have a very robust [bike] master plan and downtown specific plan [...] that the council approved, that calls for all these multimodal projects.” Segal continued. “And this is literally the least we can do. If we can't get past this hurdle, we're not going to actually implement any of those plans.”

The supporters were quite outnumbered though by residents who say this is a nonsensical project.

“Who doesn't want safer streets in South Pasadena?” asked Stacy Sharkey, a 27 year resident of Floral Park Terrace (parallel to Grand). “But I think the execution and the selection of some of the locations is questionable,” she added.

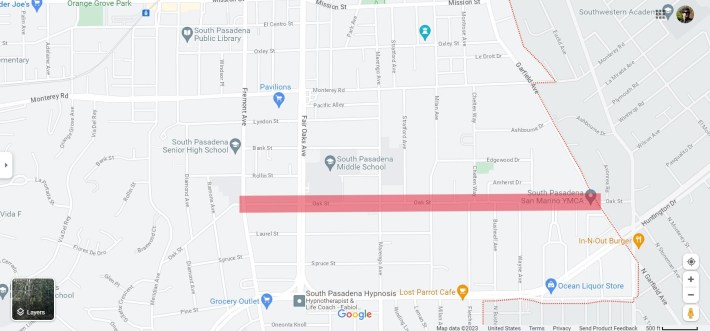

Sharkey’s main issue was with the plastic delineators marking temporary chicanes on Hermosa Avenue, which crosses Grand. Note that Hermosa curves and continues uphill as Hermosa Place, where a short climbing bike lane was installed as part of the project.

“So there's never been an issue with this stretch of Hermosa [between Grand and Floral Park], and this installation has now created a problem when there was never one,” said Sharkey. “Now it's such a small area between Hermosa Place and Grand Avenue, and then there are these sections now that force both sides of traffic to the center of the street. So this is now narrowing Hermosa, and for the residents of Floral Park Terrace going in and out, it just converges in a very small area.”

Several commenters questioned the necessity of it all, given that there were no traffic studies done specifically for the project. At the meeting, Peña did tally off six collisions along Grand for the last decade, including one cyclist and one pedestrian injured, in addition to property damages and a DUI.

Wouldn’t it then make some sense to slow traffic in the area a bit, by giving a little more space to cyclists and pedestrians? Grand resident Steve Koch says no.

“Bike lanes are intended to help cyclists through where there isn't enough room for cars and bicycles to share the road safely.” explained Koch. “That's not the case on Grand Avenue, which is a straight, wide street with an excellent safety record. The project I would argue is actually making our streets more dangerous. Since the bike lanes went in, we've had walkers, joggers, joggers with baby strollers – who used to use the sidewalks – now they're in the bike lanes.”

“Strollers and runners in the bike lanes? That's awesome,” Jason Claypool followed up. “They must feel safe and entitled to the space, and I think we should continue to encourage that.”

Claypool is an architect who lives just off of Grand, and said he chaperones regular bike rides to school for his children as well as some neighbors’ kids.

“The Slow Streets program on Grand Avenue makes this possible with bike lanes, and the traffic calming measures at Hermosa – slowing down the motorists at that intersection – is critical to the community's safety.” said Claypool.

Most residents at the meeting agreed Grand was a pretty safe street, and seemed more concerned about drivers and property values. When resident Barbara Hoskins excoriated the project team, applause erupted.

“If you had a problem in your home, I'd like to suggest that first you would look into how much damage it is causing. And then do we want to do anything about it? Secondly, you would look at the expense of it. And then thirdly, you will look at the aesthetic of it. I'm sure you would not plan something for your own homes that really disrupted the architectural value, and the aesthetic of your home. Whoever designed this project, really had none of those three things in mind.” Hoskins declared.

“All of a sudden, we wake up and there are these white posts everywhere. And large sections of streets are sectioned off so that it becomes more dangerous, because you literally can't drive around these things easily.” she said.

By the time public comment was over, it was easy to see which way the wind was blowing.

Councilmember Janet Braun called the project a case of “the tail wagging the dog” in South Pasadena, a dropped baton from one city council to the next. She said, “This all started in 2018 and 2019. None of us were really around for this.”

“And we voted for this in 2023 because the work had been done.” Braun said. “And so we just thought, ‘Okay, well, it's temporary. So let's just try it.’”

Braun said she supports multimodal infrastructure projects, but not like this. “We need to figure out a way to make South Pasadena a more walkable and bikeable city.” she said. “I would prefer to go forward with a strategic approach to a biking and walkable plan, rather than once again having a three block bike lane that doesn't connect to anything, and bulbouts, which were a disaster pretty much everywhere else in the city [along Oak Avenue]. So I think this is a big mistake.”

After some fussing around on how much exactly to tear out, the council voted unanimously to support a motion by Councilmember Jon Primuth to

- remove the bike lanes on Grand

- remove all plastic delineators along Grand and Oak

- keep the stop limit lines

- and keep the short uphill climbing bike lane on Hermosa Place.

Primuth requested that Public Works study whether the red curb along the Hermosa Place bike lane needs to be kept red.

“The question is, do we have to remove the red curb or not - to allow parking - [in] which [case] [...] the bike lane is useless, it's completely cut off?” Primuth asked, wondering if a sharrow might be better.

Transportation Program Manager David Peña more or less concurred that removing the red curb paint would compromise the bike lane’s usage, and Transportation Commissioner Diego Zavala said earlier in the meeting that installations on Hermosa weren’t messed with like those on Grand.

“Interestingly, up Hermosa there was almost no need to visit any of the installations except for slight rain damage. This is an indication that their designs are not as intrusive as once claimed early on by critics.” Zavala said.

Streetsblog’s San Gabriel Valley coverage is supported by Foothill Transit, offering car-free travel throughout the San Gabriel Valley with connections to the Gold Line Stations across the Foothills and Commuter Express lines traveling into the heart of downtown L.A. To plan your trip, visit Foothill Transit. “Foothill Transit. Going Good Places.”Sign-up for our SGV Connect Newsletter, coming to your inbox on Fridays!