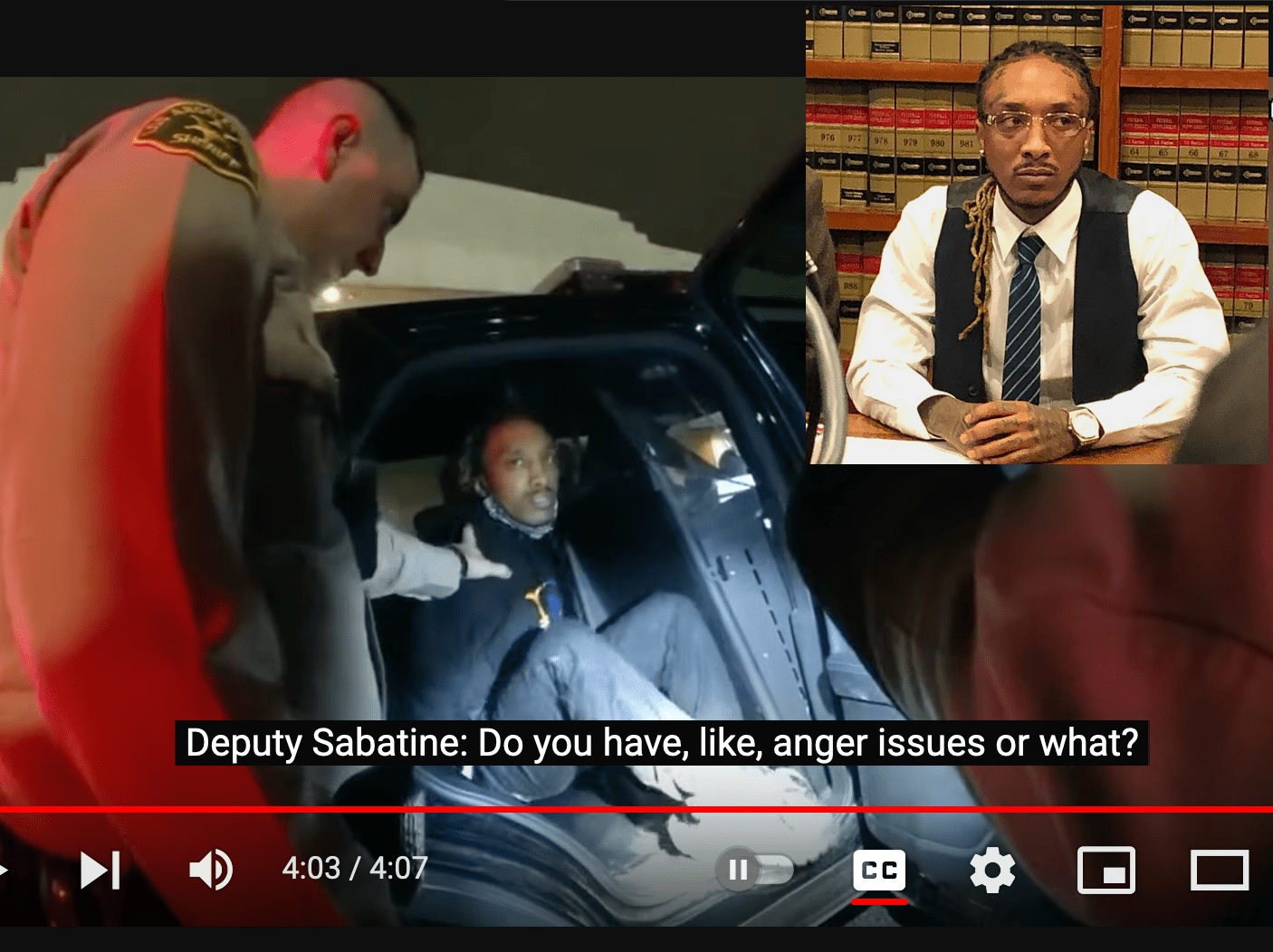

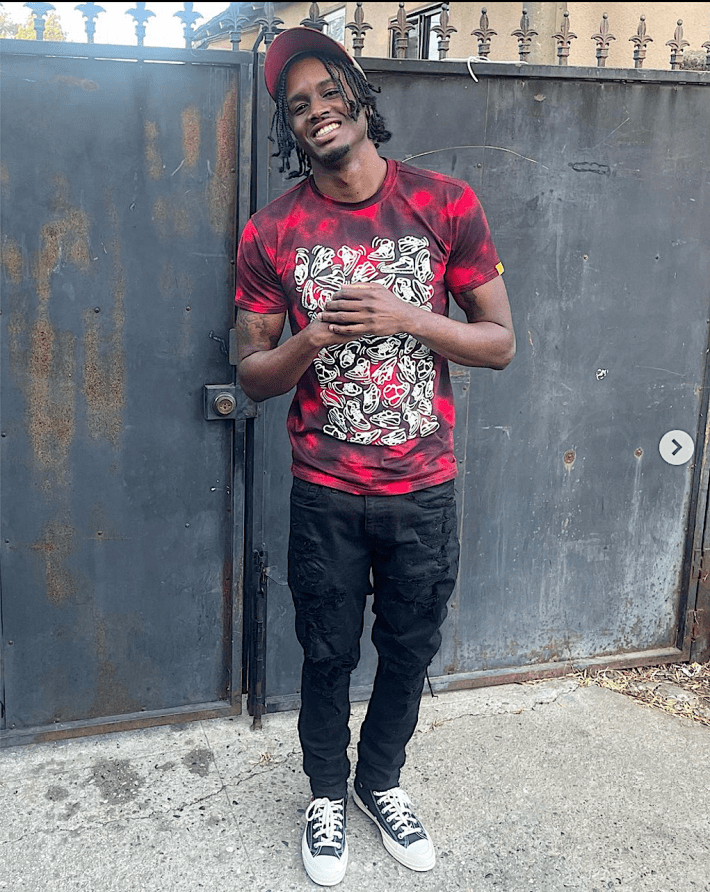

In body cam footage released by the L.A. County Sheriff's Department (LASD) on January 6, Deputy Justin Sabatine is heard gaslighting 34-year-old Darral Scott as deputies put the handcuffed rapper, known professionally as Feezy Lebron, in the back of Sabatine's patrol vehicle.

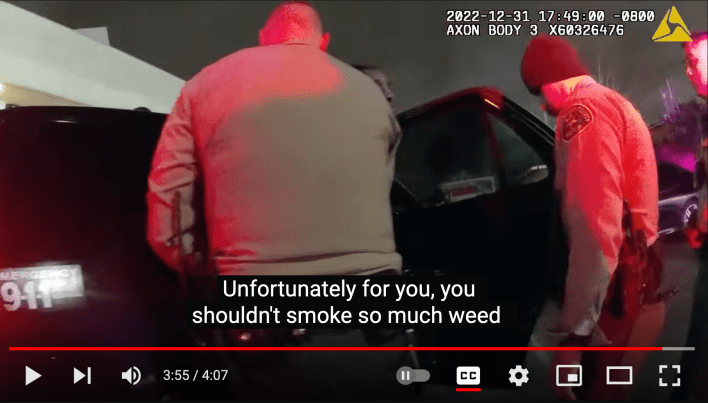

After expressing annoyance at Feezy's repeated refusal to give deputies consent to search his vehicle, Sabatine tells him, "Unfortunately for you, you shouldn't smoke so much weed in your car. Then we wouldn't have to search you."

It is the first time Feezy has been given a reason for his detention since deputies pulled up on him as he sat - lawfully parked - waiting for a friend in the parking lot of a weed shop near 149th and Crenshaw just before 6 p.m. on New Year’s Eve.

He's kept his cool throughout the harrowing encounter, including as Sabatine gave him conflicting commands while pointing a gun in his face and threatening to blow a hole in his chest for his alleged noncompliance.

But hearing Sabatine conjure up a bogus justification touches a nerve.

Sabatine is clearly performing for an audience: anyone who might have cause to check his body cam later and the two deputies who had just arrived in response to the call for back-up (seen above) and who don't know what Feezy is or isn't guilty of.

He also appears to be signaling to his junior partner, Deputy Jacob Ruiz (who was still a trainee in 2020), to keep his mouth shut.

Ruiz - by virtue of having been the one to first approach Feezy, ask if he was smoking weed multiple times, and reach into the vehicle to try to pull him out - would have known Feezy had not been smoking. But he opts to follow Sabatine's lead and says nothing.

Feezy can't let it slide. He calls bullsh*t on the manufactured probable cause.

"I didn't smoke no weed in my fucking car," he says, repeating what he had told Ruiz when the deputy first appeared at his window. "I have weed in my fucking car. I didn't smoke no weed in my fucking car. It's not illegal [to possess it]."

Deputies would eventually ticket Feezy for a missing front plate because they couldn’t pin weed smoking on him. But if Sabatine is concerned he'll have to justify his actions, he doesn't show it.

Sounding almost giddy, he snarks,"Do you have, like, anger issues or what?"

Watching the footage back later, Feezy says this was the moment that felt like a slap in the face. “I was angry, but I was sad - I was everything at the same time. Like, are you serious? You just threatened to kill me repeatedly and you asked if I have anger issues...?" Feezy shakes his head. "I was just in shock.”

A month on, he remains shaken to his core. But the incident has also given him new purpose.

Since audio of the encounter went viral on social media, he’s been deluged with messages from people telling him about their own traumatic experiences with law enforcement. “They could relate to not having control, to feeling like a victim, to feeling like, ‘I’m gonna die for no reason’…” he says. It pushed him to try holding the department accountable "before this happens again in the worst way” to someone else.

The $10 million civil rights tort claim filed on January 18 on his behalf by firms Hadsell Stormer Renick & Dai LLP and Cohen Williams LLP is a first step in that process. If LASD rejects the claim outright or opts not to settle within the allotted 45-day period, he will be able to move forward with a lawsuit in state or federal court.

Feezy is steeling himself for what's to come. "I just wanted to get home to my family for the countdown to the New Year," he says. "But I almost didn't make it home...and that's stuck with me."

_________

Making sense of the body cam footage

That the world is even aware of what happened to him on New Year’s Eve is itself something of a miracle. He'd been unable to do IG livestreams for several weeks prior to that night. That he managed to launch one right before he would end up needing it most felt like a sign to his family.

Feezy hadn’t been sure anyone would care when he first posted it – it was just audio and he had survived the encounter. He wondered if people would be able to see that this was how Black men like himself – through no fault of their own – could end up dead during traffic stops.

The clip quickly racked up hundreds of thousands of views and was reshared across multiple platforms by people decrying Sabatine's threats. [See SBLA's initial coverage here.]

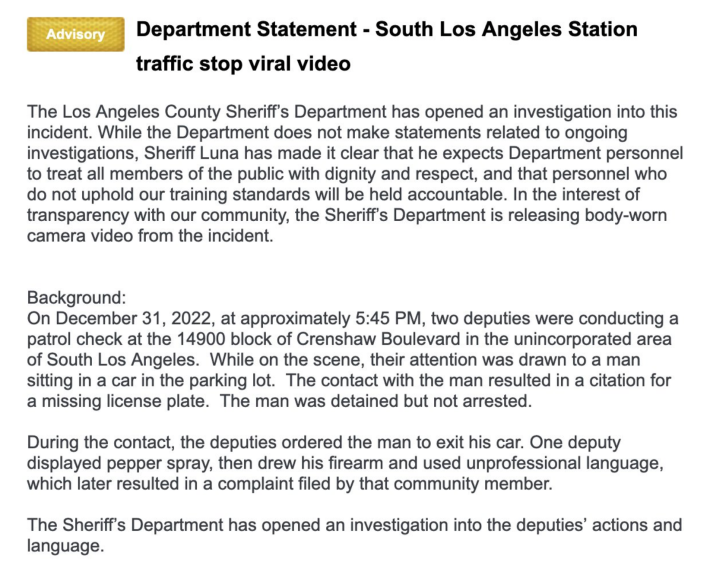

It was the Sheriff’s Department that took a minute to catch up. They did not issue their first public acknowledgement of the stop until January 6. And when they did, it was deeply underwhelming.

It did not address specific questions this reporter submitted regarding the stop itself, the threats Sabatine made, the extent to which deputies regularly escalate encounters, Feezy's treatment at the station, or whether LASD would be releasing a briefing video on a fatal shooting Sabatine was involved with in September of 2022.[1]

The statement also significantly narrowed the scope of the investigation by minimizing the gravity of what Feezy had been subjected to.

Sabatine's taunts and threats to use deadly force were lumped into the category of “unprofessional language.” The pointing of both pepper spray and a firearm at Feezy got downgraded to "displaying" and "drawing," respectively. And there was no acknowledgement of Ruiz’ role in the escalation of the stop or of his having attempted to physically pull Feezy out of the vehicle despite not having probable cause to do so.

The footage released - a 4-minute clip taken exclusively from Sabatine's body cam (below) – appears similarly intended to limit the public's understanding of both the egregiousness of the encounter and the departmental culture driving deputies' behavior.

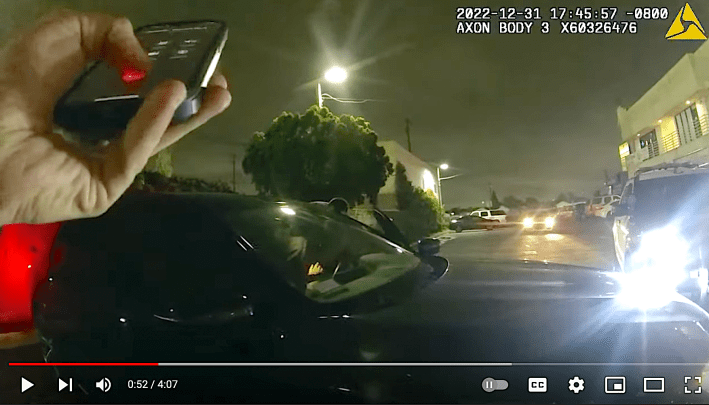

For one, because the video begins after deputies are out of their patrol vehicle and Ruiz is already positioned at Feezy’s door (below), the public doesn't get a look at what deputies saw - i.e. what allegedly motivated them to engage Feezy - as they pulled up on his vehicle. [Department policy requires that body-worn cameras (BWC) be activated prior to the initiation of stops; Sabatine did not manually activate his until he joined Ruiz at Feezy's window - well over a minute after the stop had been initiated.]

And the prolonged - and destructive, per Feezy - search of his vehicle as well as any effort deputies made to justify either the stop or their conduct are also conveniently excluded.

Feezy's own recording fills in a few of these gaps.[2]

Audio of his livestream being interrupted (below) indicates this was an investigative stop: Ruiz had approached Feezy to ask if he was smoking weed, not to ask about a missing plate. The goal from the outset was to search the vehicle, regardless of what Feezy was doing.

Ruiz can be heard asking Feezy whether he was smoking multiple times (turn on closed captions for transcript). Feezy politely says no each time. Having nothing to hide, he also tells Ruiz he has weed in the vehicle (which is legal) and explains he wasn't smoking it because he was a grown man who didn’t go around smoking in weed shop parking lots.

Despite having no probable cause to do so and without giving Feezy either a command or a warning, Ruiz is heard reaching into the vehicle, fumbling with the door handle, and attempting to pull Feezy out around the 56-second mark below.

The only explanation Feezy got from Ruiz came after the fact and was untrue: "'Cause I told you to [get out]."

Assuming Ruiz had turned his BWC on at some point, his footage would have offered more insight into just how little cover Sabatine provided as Ruiz engaged Feezy.

As detailed here and seen below, Sabatine spent the first minute of the encounter talking on the phone, wandering around, tapping away on the computer with his back to Ruiz, and making no effort to ensure his partner was safe.

That information matters because Sabatine’s positioning and actions prior to threatening Feezy with deadly force suggest he was not concerned Feezy posed a danger to either his partner or himself.

What Sabatine’s footage does help illuminate is his recklessness and his utter inability to engage a member of the public in a reasonable way.

His decision to immediately whip out his pepper spray (when he finally moves to help Ruiz extract Feezy from his car), for example, appears to be born out of impatience and a desire to exert his authority. It is not, as the footage makes abundantly clear, “to protect himself or other persons from assault, to overcome resistance to effect an arrest, or to restrain a violent person in custody,” as LASD’s use-of-force policy would require.

Similarly, when Sabatine is seen abandoning the pepper spray and pulling his gun on Feezy just a few seconds later, he again appears to be acting out of a desire to intimidate Feezy into submission.

But the commands he is giving are confusing.

Despite the fact that Feezy's engine isn't on, Sabatine tells Feezy he'll be shot if he drives off. Then he asks Feezy if he's going to comply. When Feezy asks what he's supposed to comply with, Sabatine tells him not to move his hands. A few seconds later, he again tells Feezy that if he moves at all he'll be "done," but then demands to know if Feezy is going to get out of the car while also tacking on threats to arrest Feezy and have his car towed for good measure.

Most importantly, Sabatine's footage clearly shows Feezy never makes a single threatening gesture or movement.

Instead, in anticipation of being sprayed, he is seen leaning away from the deputies and shielding his face with his arms and hoodie. He is also heard calmly and repeatedly asking why he is being told to get out of the car – something he later told this reporter was both an effort to de-escalate Sabatine and a genuine attempt to figure out what was going on. And when he does finally appear to reach for his door handle – to put a barrier between himself and the pepper spray as he waited for deputies to provide some justification for this violation of his rights - Sabatine is seen threatening to blow a hole in Feezy's chest without even bothering to give his own partner sufficient time to get out of the way.

_________

Intimidation at the station

By only referencing the stop in their statement and providing such a brief excerpt of the body cam footage, the Sheriff’s Department gives the impression that any potential misconduct was limited to the way deputies initiated the detention.

Doing so sets Feezy up to be accused of noncompliance by the law-and-order crowd and those who are unfamiliar with how aggressively Black and brown residents of gang-impacted communities are policed.

It may also make it more likely that any penalties imposed are relatively minor – i.e. a one- or two-week suspension for Sabatine, and minimal, if any, consequences for Ruiz.

Yet the lengths other deputies went to to aid Sabatine in discouraging Feezy from filing a complaint at the South L.A. Station that night speaks to the deeper systemic issues that enabled Sabatine’s behavior: namely, the department’s hostility toward the South L.A. community and the contempt it holds for those who would question its authority - young Black men, in particular. It's also, his lawyers contend, a violation of his 1st Amendment right to seek redress from a government agency without fear of reprisal.

Feezy’s recordings captured some of what that looks like in practice. On tail end of his livestream, Sabatine can be heard goading him after he indicated he was considering filing a complaint. And in a separate recording made at the station, Sabatine is seen engaging in verbal intimidation while two other deputies stand silently by.

When Sabatine suddenly appears in the lobby (above), he tells Feezy there is no cause for complaint and that the citation for the missing plate was proof the stop was lawful.

The implication is that the existence of a citation – even one explicitly written to provide deputies with cover for just this kind of scenario – gives Sabatine license to bully and threaten members of the public with impunity.

It's a ludicrous notion, but Sabatine sounds pleased with himself. “I’m just letting you know your complaint is unfounded,” he reiterates as he saunters away. Then he laughs and points to his body cam, telling Feezy the stop was recorded “to protect us from people like you.”

Sabatine wasn't the only deputy to actively confront him at the station or minimize his complaints, says Feezy. “I figured [this is] what happens with a lot of Black guys...They make it impossible for us to file a complaint because they want us to leave.”

He certainly would have preferred to leave. It was New Year’s Eve, he was stressed, he was exhausted, and hearing excuse after excuse from deputies about why they couldn't assist him for nearly four hours heightened his unease. “But I told myself I just couldn’t [walk away]. This has happened too many times.”

It took Feezy’s family members and a family friend who had retired from the department showing up for deputies to finally attend to him. They weren't done until after midnight.

_________

A trail of trauma

Despite having been hassled and harassed by police many times before, this was the first time police had put a gun in Feezy's face during a stop.

It's left him traumatized. He hasn’t been sleeping and he’s been having panic attacks – to the point that he took himself to the emergency room a few days after the incident.

Even driving his car induces anxiety, he says. Outside of having to take the kids somewhere, “I barely drive anymore. Even the thought of a police car getting behind me – I’m thinking [in terms of] life and death now.”

Compounding the stress is the emotional strain it’s put on his family. His kids – aged 9 and 16 – have been struggling with how to process how their dad was treated. Feezy’s cousin, Yenn Menia, and Sarena Wilson, the children’s mother, both spoke of how painful it was to see him rendered so helpless in the footage. And by continuing to speak up, the family feels like there are targets on all of their backs.

“It’s been life-altering for the whole family,” Menia says of the upheaval this one encounter has caused.

But Feezy finds no comfort in hunkering down at home. The stress of waking up in the middle of the night and thinking the noises he's hearing are the sheriff at his door has been too much. Relocating in a rapidly gentrifying community is no small task, but Feezy says he won't be at ease until his kids are safe in the new spot.

“I just don't feel safe,” he says. “I haven't felt safe since the situation happened.”

They have good reason to be concerned. LASD has a long history of retaliation against the families who have spoken up on behalf of loved ones hurt or killed by the department.

Yet they are all resolved that speaking up was the right thing to do.

It was that recording that made Wilson feel that this was so much bigger than them. “I told him to just do it,” she says of supporting Feezy’s decision to pursue legal action. "Not just for himself, but for other people like him. For our kids. Something needs to happen.”

“There are so many of us” that have experienced harassing or aggressive stops on a regular basis, agrees Menia. But “not everyone has the evidence” that Feezy had managed to capture via his livestream.

And even when people do have the evidence, the power the department wields over the community can make them hesitant to file complaints.

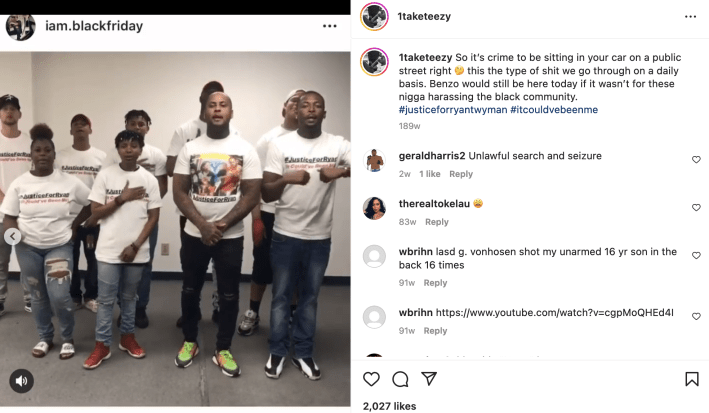

Such was true of 1 Take Teezy, a 29-year-old rapper and producer from Compton (at right), who caught an aggressive encounter with deputies on his phone back in 2019.

He'd been sitting in his vehicle in front of his residence when he saw deputies hassling other people as they made their way up the street. Knowing he couldn't drive off without being accused of evasive behavior, he resigned himself to recording the inevitable interaction and waited for deputies to make their approach (below).

As in the encounter with Feezy, it is clear the deputies' goal is to get a look inside his car, regardless of whether they have probable cause.

And, as in Feezy's case, deputies ignore Teezy's questions about why they are reaching into his vehicle, make a bogus justification for trying to pull him out of the car (claiming he did not have a license when he told them he did), and threaten violence when he tries to assert his rights.

"Bust it?" says Teezy of the threat to smash his window. "The fuck?!"

Though the video is just under a minute long, the interaction dragged on for some time. After finally getting him to hand his license over, Teezy says deputies tried to use it as leverage - refusing to give it back unless he got out of the car (and eventually tossing it in the street when he didn't).

He says they also threatened to run the plates on all the cars along the street to try to find something that might trigger a citation or a tow. Some of those cars were tied to his side business, suggesting deputies had been keeping tabs on his residence. It left him thinking about the way the department labeled community members and the entitlement with which they disrupted people's lives.

"Every time I've been in that [kind of] situation, they try to make it seem wrong that I'm exercising my rights," Teezy says of the many times deputies have torn his car apart for no reason. They "take it to the extreme - snatching your door open...talking about how he's gonna bust my window, all type of stuff like that" to shut down questions about their actions. "Like, what makes you so comfortable to do something like that?”

The Highway Patrol, which also has jurisdiction in that area, doesn't usually tell him to get out of the car, he says. "But with the sheriffs, it's a 95-percent chance they're gonna take you out the car. They're gonna search your car, even though you're not giving them permission to or nothin' like that. That's just what they do."

Not even Aja Brown, the mayor of Compton at the time, was exempt from that kind of treatment. The same month that Teezy was harassed, deputies ordered her, her husband, and their infant daughter out of their car so they could be searched for drugs.

But even with video of his stop in hand, Teezy didn't feel comfortable trying to file a complaint.

Maybe if he'd thought something would come out of it, he would have considered it. But he says he doesn't see it bringing him anything but grief. "You could go complain about this certain officer and that officer still gonna be [patrolling] in the same area. But now [he has] developed a vendetta against me...so it's probably not going to be a good end to the story when I run into this guy again."

If even the mayor of Compton couldn't get her complaint resolved to her satisfaction, how could regular citizens be expected to take on so much risk?

As far as Feezy is concerned, the department has a long way to go to show it's even taking his complaint seriously.

There was no mention of the intimidation at the station. And the labeling of Sabatine's threats as "unprofessional language" strikes him as deeply "disrespectful."

"'You move and you're going to take one right to the chest,' 'You move and you're done,' 'I want to shoot you, absolutely'...," he says, parroting Sabatine. "Would you consider that [just] 'inappropriate language' if I was your child? Or a family member?" he asks. "That officer literally threatened my life and was ready to take my life at that moment."

The only conclusion he can draw from the Sheriff minimizing what happened to him is that they "don't value my life or the lives of people that look like me." And that disciplining one or two deputies won't be enough to fix that. Or keep his son from having to go through a similar experience in the future.

"I just think about the people we see on the news," he says of the recent deaths of teacher Keenan Anderson (who was tased 6 times in 42 seconds by LAPD after he was involved in a traffic crash) and Tyre Nichols (who was savagely beaten by Memphis PD after he fled during a traffic stop). "People usually don't come out alive of these situations to tell the story."

Instead, he says, you get law enforcement's version of what happens, which usually depicts the person - and Black men, in particular - as being the aggressors who were responsible for their own death. In raising his voice on their behalf, he hopes to shed some light on the role officers' aggression and deliberate escalation play in these deadly outcomes so that something can finally change.

“You should be able to sit in your own car without being in fear for your life.”

_________

The deaths of Tyre Nichols and Keenan Anderson have revived national and local debates around the role of law enforcement in traffic stops. Unfortunately, getting LASD out of traffic stops would likely not have prevented either Feezy or Teezy from being stopped. As it is, LASD is technically already out of the business of traffic enforcement in the unincorporated Alondra Park/El Camino Village area where Feezy was stopped - primary responsibility for traffic enforcement falls to CHP there. We'll be diving into the complexities of that issue and pretextual stops more broadly in a follow-up story. In the meanwhile, find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman

[1]Re: Deputy Justin Sabatine's involvement in the fatal shooting of 41-year-old Rushdee Anderson on September 2, 2022. Details are scarce, but it appears that while responding to a report of a man with a gun, Sabatine and his partner first detained the wrong man in front of Anderson’s residence and then shot and killed Anderson after deputies allege he emerged from the home and picked up a gun that they say had been lying on a chair on the porch. The deputies claim Anderson then pointed the weapon at them, prompting them to open fire. Though it is likely Sabatine was wearing a body cam during that shooting, footage of the incident has not been released. LASD has not responded to this reporter's questions about this incident.

[2]Re: Feezy's livestream. Find the full livestream recording here. Of interest - Sabatine muttering and appearing to find Feezy's ticket for a missing plate while searching the vehicle happens around min. 12:50. (Feezy argues that finding that ticket gave deputies the idea to cite him for the plate, as they had not mentioned it until after searching the vehicle.)