In 2017, Metro officially cancelled the $6 billion 710 Extension Project in the Northwest San Gabriel Valley. As some funds for the 710 freeway corridor had already been approved by voters, Metro undertook a process to redistribute those funds to corridor cities. That process so far has been disappointing, as Metro chose to fund projects (see Streetsblog coverage of the project lists from 2018 and 2019) predominantly focused on increasing car capacity throughout the region. However, a decision by the Pasadena City Council gives Metro another chance to get it right.

On Monday, the Pasadena City Council voted to reject a proposal to construct a $400 million grade separation project for the L (Gold) Line where it crosses California Boulevard between Arroyo Parkway and Fair Oaks Avenue. Since completion of the L Line, car congestion along this corridor has increased during rush hour. The grade separation would have eliminated car vs. train conflict at one grade crossing. This would have benefitted both drivers and transit riders; trains would have run more reliably and wouldn't briefly block car traffic.

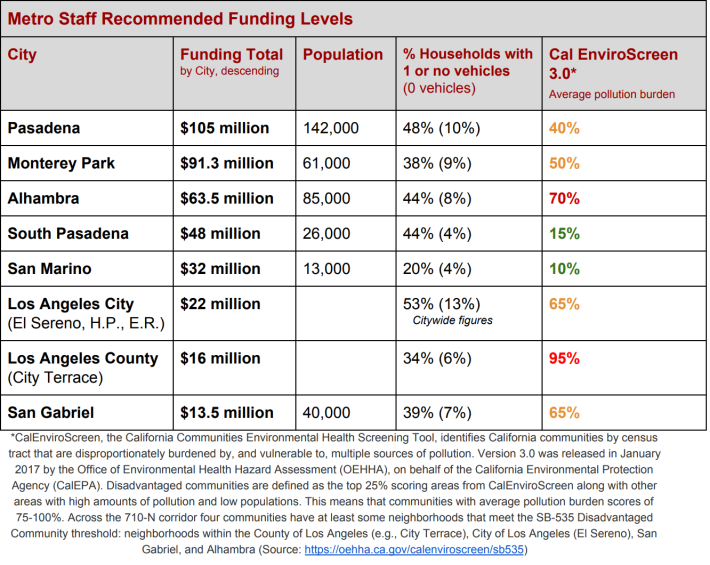

Metro had approved $105 million towards the project in 2018 - then expected to fund nearly all of the project budget. Added: Metro later added $125+ million more for the grade separation project, bringing the total allocation to $230.5 million.

This week the city council decided that grade separation construction time would have been too long; estimates ranged from 18 months to four years. The council hopes that the funding will remain in the city of Pasadena so they can move forward with other projects designed to improve mobility there.

What those substitute projects will be remains to be determined.

City staff were directed to create a list of potential transportation projects that the grade separation funding could use. These might include reduced (or free) fares for the city's transit system, implementation of complete streets, first-mile/last-mile connections to the L Line, safety/reliability improvements to keep trucks from crashing into the L Line - or could be yet more projects designed to increase car capacity. When city staff completes its list, the Pasadena City Council will have a chance to approve it before it is submitted to Metro.

From there, it is unclear how Metro will re-program the funds.

In the past, Metro's Highway Program held a wholly opaque process - selecting projects then putting them to the Metro Board of Directors for approval. Despite both the Metro Board of Directors and San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments supporting greater flexibility in how highway funds can support multi-modal transportation, Metro, under the leadership of Senior Executive Officer Abdollah Ansari, has rigidly stuck with car-centric projects and rejected multi-modal ones, undermining Metro's environmental and equity directives. In just the past several months, Ansari has openly mocked transit, bicycling, and Metro's public input processes, contradicted Metro agency partners in criticizing them for lack of full-speed ahead support for harmful freeway widening, complained about Metro inclusion of equity and race impact assessments, and has been broadly hostile to environmental regulations and oversight.

If the process is similar to the prior iterations, once Ansari's Highway Program picks winners, what is left of Pasadena's project list will go to the Metro Board of Directors for approval.

In 2018 and 2019, advocates flooded the board with requests not to approve the Highway Program's list of car-centric projects to be funded by remaining 710 monies. The advocates noted that they would worsen both congestion and increase California's carbon footprint as climate change wreaks devastation. Despite some board pushback in 2019, the Metro board approved both project lists.

If the Pasadena project list that heads to the board is another car-centric disaster, it will be up to the Metro Board to make a last stand third chance to get it right.

Similar to other governmental agencies, many Metro boardmembers defer to the local Metro representatives, giving them an outsized role in deciding the fate of Pasadena's project list. The two Metro directors representing the region are Kathryn Barger, the only Republican member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (most of the San Gabriel Valley is represented by the more progressive Hilda Solis, but not Pasadena) and Pomona Mayor Tim Sandoval. While there is little reason to believe that Ansari or Barger are likely to suddenly embrace multi-modalism; there have been changes to Metro leadership since 2019. One is the election of Sandoval to the board replacing the retiring John Fasana.

Another major change is the replacement of Metro CEO Phil Washington with Stephanie Wiggins. After taking the reins of the agency this summer, Wiggins promised to change the culture at Metro - including putting the rider experience first, and prioritizing equity and climate. What projects the agency chooses to fund with this $105 $230 million will be an early test of whether or not that culture change is taking root.

Even the project selection process - which was utterly opaque in 2018 and 2019 - will show Metro's current commitment to transparency. Or lack thereof.

SBLA San Gabriel Valley coverage, including this article and SGV Connect, is supported by Foothill Transit, offering car-free travel throughout the San Gabriel Valley with connections to the new Gold Line Stations across the Foothills and Commuter Express lines traveling into the heart of downtown L.A. To plan your trip, visit Foothill Transit. “Foothill Transit. Going Good Places.”

Sign-up for our SGV Connect Newsletter, coming to your inbox on Fridays.