Editor's note: This article originally appeared on Sidewalk Talk and is republished with permission. Read Streetsblog's earlier coverage of the study explored below here.

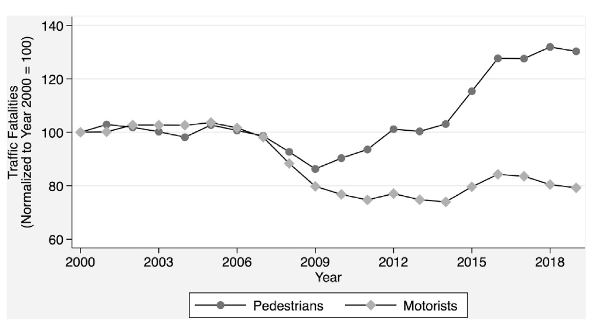

Last month, Vox reported on the public health crisis of car deaths in America, noting the alarming rise of pedestrian deaths in particular. From 2009 to 2019, the annual number of pedestrians killed by cars rose at least 51 percent, with some estimates reaching 87 percent. Over that same period, the annual number of drivers and passengers killed by [drivers] of cars stayed roughly the same.

There are many reasons why the story of car fatalities in U.S. cities has forked so sharply in two directions. Streets designed for high speeds and vehicle priority are certainly a major contributor, as described well by Vox. But new research points to another key factor in the troubling trend of pedestrian deaths: the growing size of vehicles.

That’s the conclusion reached by economist Justin Tyndall of the University of Hawaii, in a study recently published in the journal Economics of Transportation. Analyzing data from 2000 to 2019, Tyndall estimates that hypothetically replacing SUVs with standard cars in U.S. cities would have averted nearly 3,300 pedestrian deaths, and that replacing all light trucks (defined as SUVs, pick-ups, and minivans) would have averted more than 8,100 fatalities.

The work suggests the urgent need for policy, design, and tech innovation directed at the safety problem, which Tyndall concludes will only rise in the absence of strong intervention:

Average vehicle size has undergone a sustained increase over the past 20 years, with no signs of abating. If the popularity of large vehicles continues to rise there is likely to be a corresponding increase in pedestrian fatalities.

Let’s take a closer look.

What they did

As pedestrian deaths have risen in recent years, so have the sizes of vehicles on U.S. roads and streets. Tyndall’s study notes that from 2000 to 2019, the average vehicle weight increased nearly 11 percent, the share of SUVs on the road reached 21.5 percent (an 8 point rise), and the share of heavy vehicles (over 2,500 kilograms) involved in fatal crashes increased fivefold to 12.5 percent.

Larger vehicles may be safer for their own passengers, but they pose greater risks for everyone else on the road. Generally speaking, heavier cars are harder to stop and have more force on impact. When it comes to pedestrians, in particular, larger vehicles hit people higher up on the body, creating the potential for more serious torso or head injuries instead of leg injuries.

While previous research has found a clear connection between vehicle size and pedestrian injuries, Tyndall’s work examines a much more recent period. (At the time of the study, 2019 was the most recent year for reliable pedestrian statistics.) Tyndall also focuses on the metropolitan area level, which makes sense given that interactions between vehicles and pedestrians occur most frequently in cities.

The study analyzed public data on traffic fatalities, vehicle types, and vehicle weights, covering more than 700,000 crashes involving more than 108,000 pedestrians across 358 U.S. metro areas, from 2000 to 2019. Recognizing that many factors contribute to a given crash, Tyndall tried to isolate the impact of vehicle size as much as possible by controlling for other variables, including alcohol-related crashes and population growth.

What they found

Tyndall’s analysis produced a number of striking conclusions. Let’s focus on three in particular:

Overall, larger vehicles were related to more pedestrian deaths. For the average U.S. metro area, a 100 kilogram increase in vehicle size corresponded to a statistically significant 2.4 percent increase in pedestrian fatalities. The impact of light trucks (again: SUVs, pick-ups, and minivans) was even more significant. In an average metro area, for every 10 percent of vehicles that rose in size to light trucks, there was a 3.6 percent increase in the pedestrian fatality rate.

As a further point to the importance of weight, Tyndall found that motorcycles had a highly significant negative impact on pedestrian deaths. The more motorcycles making up vehicles on a metro area road, the fewer pedestrian fatalities.

While larger vehicles protected their own drivers and passengers, they offered no benefits to motorists on the whole. Overall, Tyndall’s analysis found no statistically significant relationship between vehicle types and weights and deaths of people driving or riding in cars. But Tyndall did find “some evidence” that larger vehicles improved occupant safety. The result is a twisted arms race where people may try to purchase a larger car to protect themselves, with pedestrians and occupants of smaller vehicles suffering greater fatality risk as a result.

In Tyndall’s words, this finding “suggests that driving a larger vehicle offloads fatality risk from the occupants to other road users.”

Replacing light trucks with standard cars would save lives. Finally, Tyndall ran the numbers to see what would have happened in a world without rising vehicle size. As noted above, from 2000 to 2019, hypothetically converting all light trucks into standard cars would have saved 8,131 pedestrian lives — or, put another way, it would have averted nearly 10 percent of all pedestrian deaths. The same full replacement of SUVs with standard cars would have saved 3,283 pedestrians.

And if the share of SUVs among all vehicles had simply remained fixed at Year 2000 levels across the whole time period, an estimated 1,084 lives would have been spared.

What comes next

The research comes with some caveats. While the study tried to isolate the impact of vehicle size on pedestrian death, it didn’t control for every single factor that goes into a fatal crash. The role of distracted driving would be especially interesting to consider for future research, since the rise of smartphones and in-vehicle navigation systems occurred over the same time period as the spike in pedestrian deaths.

For now, there’s more than enough evidence to prompt action. From an urban policy perspective, one of the most direct ways to improve pedestrian safety is reducing speed limits on crowded city streets. In recent years, safety groups have pushed for speed limits of 20 miles per hour, noting the dramatic increase in a pedestrian’s chances of survival. The City of London is on the verge of considering an even stricter citywide limit of 15 mph to improve safety, according to veteran transportation reporter Carlton Reid.

Innovative street design can also play a critical role, especially in partnership with speed limits. The complete streets movement, designing streets for use by many different types of travelers, has led to major safety benefits in cities around the world. Building on that approach, Sidewalk Labs has proposed a people-first street network that separates fast-moving vehicle and transit traffic from slower-moving bike and walking trips, with an eye toward improving safety while overall preserving mobility.

Tyndall’s research also shows how policy can support design upgrades. The study estimates — in a strictly economic sense — that SUVs would need to cost $750 more to balance out the social risk they create for pedestrian safety. It’s not hard to imagine such fees being routed to cities to help implement complete streets or other policy changes, perhaps through a federal pool distributed by metro area need.

Technology can help address the problem, too. Just as back-up cameras became standard features for all vehicles in response to a child safety problem, it stands to reason that larger vehicles might eventually need to adopt stronger general pedestrian-detection and vehicle-response features than currently exist. There’s no single factor in — or quick fix to — pedestrian deaths, but recognizing the role of vehicle size helps city leaders and urban innovators alike take steps in the right direction.