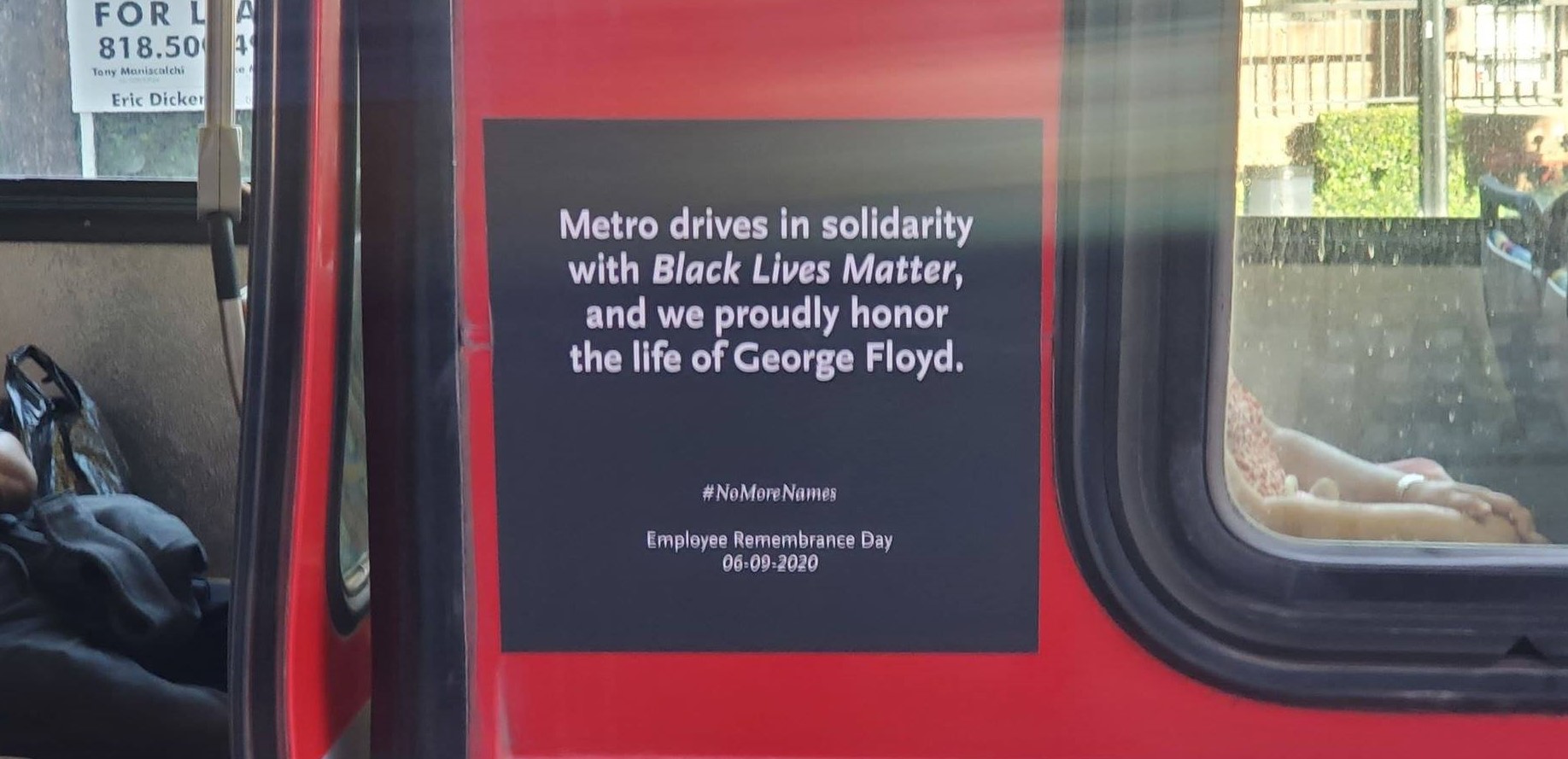

Last week, Metro's posted its "statement on Black Lives Matter and our commitment to fighting racial injustice."

The post includes Phil Washington's own harrowing experience with racist policing as a teen in Chicago, when police drew their guns on him and his mother, and underscores the importance of having someone at the helm who understands some of the barriers to mobility faced by such a large percentage of Metro's ridership.

The agency itself, however, has been slow to reflect that perspective in its policies and practices.

I am a fan of Metro. I want the agency to be successful, to be a public agency that bucks some mainstream thinking to midwife a Los Angeles County that is more equitable, sustainable, and healthy. Metro does a lot of good work that serves the least privileged among us, including Black communities, immigrants, youth, and the elderly.

Unfortunately, in many ways, Metro is also embedded in broader inequitable societal structures. This critique applies to both agency staff and the board, which consists of elected officials and their appointees. Though there are exceptions, most Metro staff - and pretty much all of its board - get around by driving and have difficulty relating to riding transit and transit riders.

I was pretty disappointed with the Metro statement, especially this section where it recounts "acknowledging what has come before."

It is impossible to go forward without acknowledging what has come before. Bus service that carries most of our riders — who tend to be Black and Latino — was allowed to erode. Freeways were built through minority communities while more affluent, whiter communities were spared. Community engagement too often favored the NIMBYs and overlooked our core customers. Fare enforcement too often targeted Black and Latino young men.

Metro correctly identified some big Metro problems, but failed to acknowledge the agency's role in perpetuating these problems.

First, Metro mostly uses the passive voice - "Bus service was allowed to erode," "Freeways were built" - which takes agency out of the statement. Metro was (and is, and will continue to be) the agent that did these things. Metro eroded bus service. Metro built freeways. Metro overlooked core riders. Metro targeted Black and Latinx riders.

Second, it's disingenuous for Metro to label these as "what has come before" when they're embedded in the current budget and future plans.

Compare that "what has come before" paragraph with this one on "efforts at Metro... for building a better future":

We are trying to speed up bus service and make it much more frequent and build a rail system that truly connects all communities. We’re trying to improve conditions on transit for women, who comprise more than half our riders, and we now have an equity officer to help the agency better reach the communities that need us most. We’re providing minority-owned businesses with the tools they need to successfully bid for more government contracts. And we’re hoping, through our future transportation school in South L.A., to give more people the education they need to work in and shape our industry. This is a short list.

Count the number of time we/us/our are mentioned in these two paragraphs. In the "what has come before" paragraph, there are two our - both referring to objects - things done to "our riders" and "our core customers." In the "better future" paragraph, there are eight we/us/our - most are subjects including "we're trying" and "we're hoping."

Also for comparison, Metro only touts its better future efforts as "a short list" while leaving that caveat off the "what has come before" short list. The implication here is that the negatives are perhaps exhaustive, while the positive efforts just represent a sample of all the great things Metro is doing. This is hardly the case.

Many of the efforts that Metro is claiming ownership of are things that Metro staff have consistently resisted. If it weren't for the dogged persistence of boardmember Jacqueline Dupont-Walker, Metro wouldn't be doing the contracts it does with minority-owned businesses. If it weren't for the dogged persistence of the Bus Riders Union, including pulling together a coalition of organizations, Metro wouldn't have installed Wilshire Boulevard bus-only lanes, laying the groundwork for current bus speed improvements. If it weren't for the dogged persistence of boardmember Mike Bonin getting Metro to work with city transportation departments to "speed up bus service," Metro staff would have kept on blaming bus speed declines on things that Metro is not in charge of - including city efforts to improve pedestrian safety. But, yes, Metro has done and is now doing these things, and should take some credit for them.

Let's take a closer look at Metro's role in each of the supposedly "what has come before" sentences:

"Bus service that carries most of our riders — who tend to be Black and Latino — was allowed to erode."

In the 1990s, Metro (then RTD - Rapid Transit District) eroded bus service so much that the agency settled the Labor Community Strategy Center/Bus Riders Union civil rights lawsuit by committing resources to rebuilding bus service. One of the more egregious racist acts of RTD was to accept South Bay communities demands that South L.A. buses not connect directly to the beach. This service pattern has not been fixed. It's still very difficult to get to the beach on Metro buses. Even for South L.A. communities only 4-10 miles away from South Bay beaches, there is little to no direct bus service. Metro is at least looking to someday remedy this somewhat in its as-yet-unfunded Transit to Trails Plan.

Metro has passed multiple sales tax measures, each with funding dedicated to bus service, but has kept bus operations funding essentially flat. Instead of putting new sales tax monies into expanded operations, the agency has largely removed flexible funds from operations and back-filled the gap with new monies.

At the core of this is a trade-off between prioritizing transit - predominantly bus - operations vs. prioritizing building new infrastructure - predominantly rail, but also highways.

Metro leadership - the majority of the Metro board - have consistently prioritized building shiny new projects over improving day-to-day operations. Most politicians on the Metro board - prominently Mayor Eric Garcetti, Supervisor Janice Hahn, Mayor James Butts - are pushing to accelerate highway and transit construction, mostly framed these days as building infrastructure for the 2028 Olympics. Does L.A. really need $3.6 billion worth of freeway expansion accelerated for the Olympics? Especially if acceleration comes at a cost of eroding transit service?

When Metro pushes to accelerate capital spending, it sucks the air out the room, making less and less money available for transit operations. Other operations funds get suckered away to expensive "innovative" microtransit and mobility-on-demand pilots, that serve far fewer riders than money put toward bus operations.

Metro is looking to re-tool its bus service through the NextGen Bus Study, but even that worthwhile effort has been hampered by Metro constraining the budget. Metro is reorganizing its bus network, but refusing to actually add more bus service.

"Freeways were built through minority communities while more affluent, whiter communities were spared."

While many people have the misconception that Metro is just transit, large portions of Metro's sales tax measures go to building infrastructure for drivers. Metro has multiple billion-plus dollar freeway expansion projects underway right now.

Metro is currently spending more than $2 billion widening the 5 Freeway from the 605 Freeway to the Orange County limit. That project displaced homes and businesses in "minority communities."

Against strong community pushback from East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, Communities for a Better Environment, and many others representing "minority communities," Metro recently embarked on more than a billion dollars' worth of early action projects, gearing up to spend $6 billion to widen the 710 Freeway. If the Metro board's preferred design moves forward, that expansion will displace hundreds of low-income residents and will bring more polluted air - and, consequently, more disease and higher mortality rates - to low-income Latinx communities already suffering from the pollution burden of the existing freeway.

"Community engagement too often favored the NIMBYs and overlooked our core customers."

Misguided and racist nimbys dominated recent Metro community engagement, especially in Metro planning efforts for two Bus Rapid Transit projects: North San Fernando Valley and NoHo-Pasadena. At a Northridge meeting last year, a white attendee called a pro-BRT bus rider “an ignorant Oriental.” Also last year, Eagle Rock nimbys harassed BRT supporters. What did Metro do in response? Instead of sticking up for core customers, Metro - largely at the urging of boardmember Hilda Solis, who parroted Eagle Rock nimby rhetoric and false claims - surrendered to nimby demands and is now delaying these much-needed bus improvements.

Metro had been doing its core ridership dirty for some time by that point. Readers may remember how the agency vilified and even criminalized its core ridership in not just one, but two series of ill-advised PSAs.

"Fare enforcement too often targeted Black and Latino young men."

There is a ton to unpack regarding Metro's ongoing partnership with law enforcement. Metro currently has a ~$130 million/year multi-agency policing contract, mostly funding LAPD (paying these officers expensive overtime). Portions of the policing contract also go to the L.A. County Sheriffs (LASD) and Long Beach Police Department.

Not long after that contract was approved, Long Beach Police officers detained and then wrestled 23-year-old Cesar Rodríguez to the ground over his non-payment of the $1.75 fare. A train rolled into the station as Rodríguez and the officer wrestled; Rodríguez was caught between the train and the platform and crushed to death. The following year, an overzealous LAPD officer enforced Metro’s no-feet-on-seats rule by dragging a teen girl off of a subway train and calling for enough back up to field a football team.

SBLA Communities Editor Sahra Sulaiman has covered Metro patrols' criminalization of poverty, and has questioned the reasoning behind Metro's security efforts - ie: who does Metro make spaces "safe" for? Metro's law enforcement has also failed to respond to public records requests aimed at helping advocates keep Metro accountable. Some data made public in 2016 showed nearly 60 percent of those arrested by sheriffs on Metro rail were Black, despite comprising only 19 percent of rail ridership. The bulk of these Metro citations were for low-level quality-of-life violations, and many of those cited were unhoused. Yet Metro preferred to police their way into compliance rather than working more actively with outreach services to find a more sustainable solution to the problem.

Then, just a couple weeks ago, as Black Lives Matter protests grew in size and scope around the city, Metro sided with law enforcement over its own riders. Citing security concerns, the agency canceled service and stranded riders, then gave its buses over to police to shuttle detained protesters.

A few more Metro slights against L.A. Black communities that didn't make Metro's list

In planning its rail mega-projects Metro has often overlooked the mobility, safety, and well-being of Black communities.

In planning the Expo line, Metro focused more grade separations in whiter Westside areas, while running at-grade in Black South Los Angeles. Only in responding to a Public Utilities Commission appeal brought by South L.A. community activists, led by Damien Goodmon, did the agency concede the line's Farmdale Station as a safety measure for adjacent Dorsey High School. The concession still fell short of the demand for grade separation.

Insult was added to injury when, while planning for transit-oriented housing at the Expo/Crenshaw station several years later, Metro promoted renderings that completely erased the existing community.

This was nothing new, unfortunately. Metro had originally planned for the Crenshaw/LAX Line to bypass Leimert Park Village, the Black community's “cultural beating heart.” And in 2009, Metro scaled back its light rail plans, meaning the train would now run at-grade up the spine of the city's last remaining Black business corridor. Seeing both as evidence that the Crenshaw Line was not being built to serve the community, stakeholders accused Metro of racism. In 2013, they finally succeeded in getting a stop at Leimert Park Village incorporated into the plans. They would not win the fight to see the train run underground, however, inspiring councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson to propose Destination Crenshaw - a 1.3-mile-long open-air “People’s Museum” honoring Black stories, culture, and contributions that followed the train up Crenshaw. It was, he said, a way to "turn insult into opportunity" and to let those on the Crenshaw Line know they were passing through an unapologetically Black space.

Fixed it for you

Here's my fixed version of Metro's "what has come before" paragraph. My changes in bold:

It is impossible to go forward without acknowledging what we have done before, what we are currently doing, and what we currently plan to continue doing in the future. We eroded and continue to erode bus service that carries most of our riders — who tend to be Black and Latino. We built and continue to build freeways through minority communities while more affluent, whiter communities were spared. We did and continue to do community engagement that too often favored and still favors the NIMBYs and overlooked our core customers. Our transit law enforcement officers' fare enforcement too often targeted and continue to target Black and Latino young men. This is a short list.

Those aren't the only changes needed, but they're the ones that stuck in my craw the most.

I guess putting out a statement could be a sort of minimum that organizations should do, but generally I see most of these statements as largely hollow exercises in public relations. Organizations wanting to make meaningful change would be better served by looking to Tamika Butler's tweet thread urging that statements both "include what you're actually going to do as a company" and be used to ensure "[you are] actually doing it & holding yourself accountable." Perhaps, working with bus riders, core constituents, and community groups embedded in low-income communities of color, Metro can rewrite the rest, including adding those actionable commitments that Butler urges.