There are many cities in the United States with a hidden past, a history hushed up or unacknowledged, and my city is one of them.

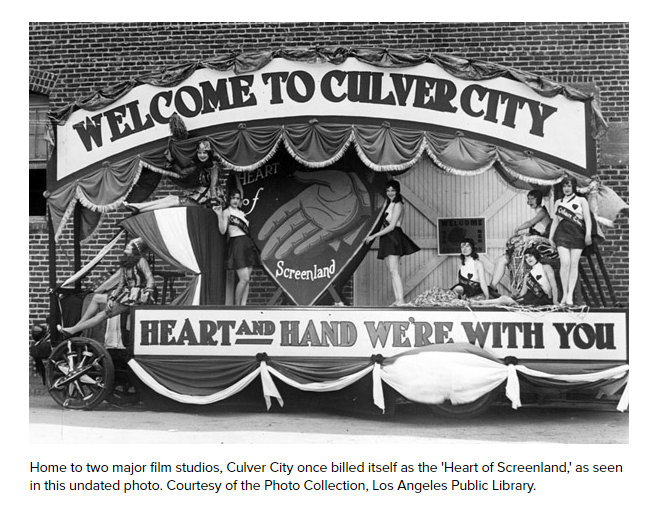

Culver City, California, is a beautiful little place nestled within greater Los Angeles. I settled here with four generations of my family almost ten years ago and we love it. The town is a little over 100 years old with nice neighborhoods, tree-lined streets, a vibrant downtown, excellent public schools, and a vibrant and diverse population.

But not long ago my sister called to tell me about James Loewen’s book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. “Did you know Culver City was a sundown town?” she asked. The book reveals a nation filled with segregated all white towns, some of which posted signs at their city limits reading “N*****, Don't Let The Sun Go Down On You.”[i] I was appalled, and immediately ordered the book. Sure enough, there we were on page 112. Why aren’t we talking about this? I wondered. And I started doing some research.

It’s not that nobody knows this hidden history.

Many do, especially nonwhites.

Kelly Lytle Hernández, one of the nation’s leading experts on race, immigration, and mass incarceration and a Culver City resident, observed in her award-winning book, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles, that in the 1920s and 30s, black musicians referred to L.A.’s suburbs as “Little Texas” or “Little Mississippi”.[ii]

In 1998, L.A. Weekly interviewed blacks and Latinos who described driving through Culver City as akin to “running a gauntlet,” with numerous stops and harassment by the police for no reason other than race.[iii]

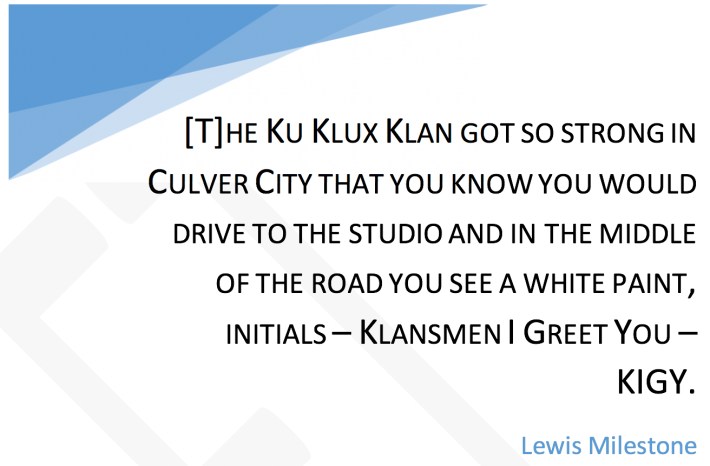

Anecdotal stories from residents living along the city’s eastern Washington Boulevard corridor testify to frequent sightings over the years of nonwhite-occupied vehicles pulled over to the side of the road by the police. And the Ku Klux Klan had a large presence in Culver City and throughout Southern California during the 1920s and 1930s and sporadically thereafter.[iv]

The Early Days and Harry Culver

It started right at the beginning.

One of Harry Culver’s first slogans when promoting his new town was, “All Roads Lead to Culver City,” with the implication that everyone could get there.

The truth, however, was quite different.

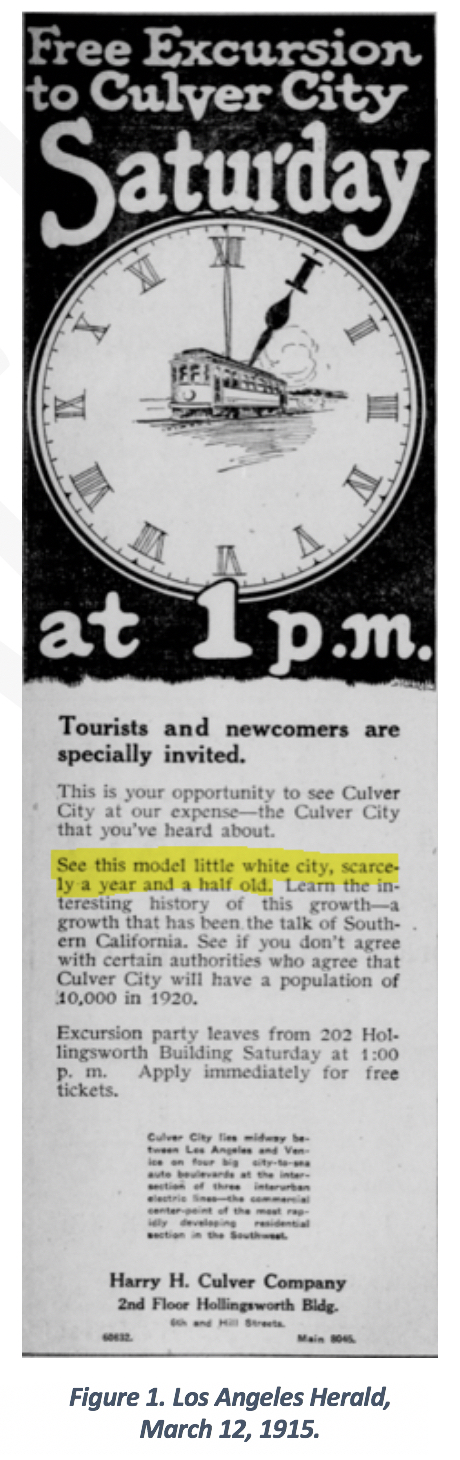

Figure 1 (at right) shows an early ad inviting people to tour the city, which announced: “See this model little white city, scarcely a year and a half old.”[v]

The usage of “white city” was both blatant and subtle racism.

In addition to the obvious implication, it also invoked the White City at the Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition in 1893. Both the fair and the White City within it were criticized by the black press at the time for being “the white American’s World’s Fair,”[vi] and are understood today to have “embodied white supremacy.” Black Americans were excluded from decision-making positions, confined to menial tasks, and the only official "black" presence at the fair was a group of African "cannibals" on the midway.[vii]

Culver’s close associate, Guy M. Rush, while selling houses in a neighborhood located near the current City Hall, was even less subtle with his pre-Christmas ads promising a present and a box of fine candy from Santa to every child who brought an adult with them. Apparently Santa was a racist because the ad (at left) qualified, “Lots and presents restricted to Caucasian race.”[viii]

In November 1914, the entire Harry H. Culver Company's sales force of “seventy men” performed in a large minstrel show to raise money for a church in Culver City.[ix] Minstrel shows were a grotesque racist caricature of black people typically staged mainly by white men in blackface performing skits, dancing the cakewalk, playing music and buffooning in ways that ridiculed black people and reinforced white supremacy.

When Harry Culver announced his plans for the city in 1913, he stated that the “tract will be subdivided into about 250 large residence lots, each with proper restrictions, and over 300 business lots.”[x] There were several implications in this statement. His reference to “large residential lots” established an economic restriction. Large lot size was a common exclusionary zoning ordinance that was “successful in keeping low-income African Americans, indeed all low-income families, out of middle-class neighborhoods.”[xi]

But, “for those wanting to segregate America, zoning solved only half the problem.”[xii] They had to go a step further, and this is where Culver’s “proper restrictions” came in. Zoning laws had to “be supplemented by deed restrictions to prevent ‘incompatible ownership occupancy’ – a phrase generally understood to mean prevention of property sales to African Americans”[xiii] and other nonwhites.

Culver became quite good at these methods. By 1927, as president of the Los Angeles Realty Board (LARB), he delivered a paper at a statewide real estate conference stating “that most responsible subdividers already exercised great control over their subdivisions through private deed restriction and land planning.”[xiv]

In that same year he also oversaw the issuing of the following opinion which makes it explicitly clear what he meant.

The Los Angeles Realty Board recommends that Realtors should not sell property to other than Caucasian in territories occupied by them. Deed and Covenant Restrictions probably are the only way that the matter can be controlled; and Realty Boards should be interested. This is the general opinion of all boards in the state.[xv]

All the realty boards in the state, then, were maintaining “proper restrictions” to segregate the state and to keep white neighborhoods all white.

These restrictions were so important to the LARB that, within months of the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer U.S. Supreme Court decision prohibiting racially restrictive housing covenants, it “announced it had drafted a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right of property owners to employ racial restrictive covenants.”[xvi] The Culver City realty board was one of “the numerous local branches that endorsed its proposal.”[xvii]

Unsurprisingly, the LARB barred blacks from becoming members until the late 1960s.[xviii]

Culver was also president of the California Real Estate Association (CREA) in 1926 and president of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) in 1929, both of which were limited to white membership and upheld race restrictive covenants. The CREA encouraged “racially restrictive housing covenants well into the 1960s,” endorsing their use “for keeping out African Americans as well as Japanese and Mexican residents.”[xix]

The provisions against “alien races” and “non-Caucasians” also “sometimes applied to Los Angeles’s Jewish population”.[xx] As for the NAREB, their 1924 code of ethics, which remained unchanged until 1950, states

A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.[xxi]

Covenant Restrictions and Enforcement

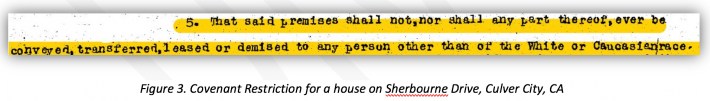

Even though they are now illegal and unenforceable, deed and covenant restrictions exist even today on residential property deeds in Culver City. Here is the wording on the deed for a house on Sherbourne Drive:

“That said premises shall not, nor shall any part thereof, ever be conveyed, transferred, leased or demised to any person other than of the White or Caucasian race.” (See Figure 3) The restrictions on the deed for the house located on Lincoln Avenue near the current City Hall allowed only residential use, confined the home’s location to a certain part of the lot, prohibited advertising, and insisted “said premises shall not be leased or conveyed to any person other than of the Caucasian race.”[xxii]

These racial restrictions have been considered vitally important to various official and unofficial players in Culver City over the years.

In November 1943, during World War II, Culver City convened a meeting of its air raid wardens in the Council Chambers at City Hall.[xxiii] The wardens were about to canvas the city’s neighborhoods to ensure families kept their lights off at night or installed blackout curtains to avoid aerial attacks. Present at this meeting were Mike Tellefson, the City Attorney, Larry Hetzler, the city’s building inspector and head of Civilian Defense, H. Teague (or Treague), affiliation unknown, Malcom S. Alexander, the head of the city’s Chamber of Commerce and a group called the Culver City for Caucasians Committee. The meeting was held under a banner proclaiming, “God Bless America” and “Life, Liberty and Justice for All.”

Tellefson “instructed the assembled wardens that when they went door to door, they should also circulate documents in which homeowners promised not to sell or rent to African Americans. The wardens were told to focus especially on owners who were not already parties to long-term covenants.”[xxiv]

“The point was stressed…that it was necessary to keep publicity down in order to insure against any friction or hard feelings from arising.” The air raid wardens were to get

…the petitions signed 100 percent; for if even one person balked at the idea the work would be useless. Mr. Teague declared, “You might find some trouble. There may be one person who says ‘I don’t mind if a Negro lives next door to me, or if I rent to a Negro.’ Try to win them over but don’t argue too much. I know how you feel if someone did talk to you like that. Deep down in my heart I would like to tell them a thing or two, but there is no use arguing too much, just turn their names over to me and I will send someone else to talk to them. We’ll find a way!”[xxv]

Tellefson was also quoted as giving his legal opinion that, “You cannot prevent an owner from selling property to a Negro, but such restrictions will prevent him from occupying it.”[xxvi]

The Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan first appeared in the Southern U.S. immediately after the Civil War. They worked to overthrow new state governments in the South while violently attacking African-American leaders.

Disbanded in the early 1870s but encouraged by and celebrated in The Birth of a Nation (filmed largely in and around Los Angeles), it reemerged in 1915. It became quite active in Southern California[xxvii] and Culver City[xxviii] during the 1920s and 1930s. In the mid-1920s, the Klan claimed “almost five million members from all walks of life,” with California known as “a strong Klan state.”[xxix]

Recognizing the significance of Birth in their rebirth and the importance of film in molding public opinion, the Klan created a “propaganda department” and actively sought to influence and produce films to spread its message.[xxx]

During the 1923 trial of 37 suspected Klansmen for a notorious raid and murder of a suspected Latino bootlegger and his family, three of the suspects were listed as working in motion pictures and one as living in Culver City.[xxxi] “In 1925, Variety claimed that two directors were involved in recruiting members from the 'film colony’ and that over 200 actors and more than 400 technical staff had already been enrolled by the Klan.”[xxxii]

While the Klan’s secrecy makes it difficult to know with certainty how many members or how much influence it had in Culver City, there are several prominent people in the film industry who have testified to their extensive presence, including George Stevens[xxxiii], a two-time Oscar-winning director for A Place in the Sun and Giant and Lewis Milestone[xxxiv], two-time Oscar-winning director for All Quiet on the Western Front and Two Arabian Knights (See callout quotes).

The Klan’s Culver City presence continued through the 1940s, including within the city’s police force, and a cross burning occurred on a black family’s lawn as recently as 1976.[xxxv]

The Culver City Police

Over the years, the Culver City police have played a significant role in maintaining the color lines in the city. In the 1940s, the Chief of Police was accused of misconduct, including openly recruiting for the Klan. The California Eagle, one of the most respected black-owned and operated papers in the U.S., reported

Citizens of Culver City are on edge this week as testimony in their City Council chamber further substantiates reports of accelerated Ku Klux Klan organization in the movie town. Hearings are being conducted by the civil service commission against veteran officer Cecil T. Truschel, former Chief of Police, who is charged with 12 counts of alleged misconduct "generally tending to lower the department's morale." More than 250 persons attended meetings one night this week and, according to reports, the sessions were redhot with testimony concerning "missing records,” “Fiery Ku Klux Klan crosses," and "solicitation of KKK membership." Unsuccessfully, through his attorney, Truschel attempted to have the testimony of C. F. Joscelyn, garage owner, who said "Chief Truschel solicited me for Ku Klux Klan membership” stricken from the records. Dept. City Clerk Rey Bott charged that affidavits signed by Joscelyn concerning the "solicitation" were missing from office files after the chief and former Councilman John Lehman privately examined the records.”[xxxvi]

There are also numerous historical reports from black entertainers and musicians who performed in Culver City. When they finished “late in the evening, they would be either arrested or escorted by police officers back to the [Central Avenue] district.”[xxxvii]

Culver City is proud of being the location from 1926 to 1938 of Sebastian’s Cotton Club, which was one of the first jazz clubs to play all-black bands and orchestras, including the Louis Armstrong Band. What isn’t usually mentioned, however, is the policy a succeeding owner described: “No colored patrons were admitted, the entertainers had their own entrance and were excluded from mingling with customers.”[xxxviii]

When Sonny Reed, a “well known musician and band leader” from the Bay area, came to Culver City in 1950 with family and friends to go skating at the Roller Dome, “they were told by the manager-owner, ‘We don't admit Negros. Negroes are not allowed to skate here, take your skating elsewhere.’”[xxxix] The manager then called the police, who accused Reed of “tampering with cars in the parking lot."[xl] “Mr. Reed denied this. The policemen said, ‘You must have been or we wouldn't have gotten the call.’”[xli]

Reed and company were then told "to clear out of Culver City and never show their faces there again.”[xlii]

In 1967, the Culver City Police Department hired its first black police officer, James Forte.

According to a profile of Forte in the Los Angeles Sentinel, “Forte discovered that there was major racism within the department.” He reported that “his first years as a police officer were wrought with name calling and challenges.” Forte experienced similar sentiments from the town’s residents, speculating “that the primary reason for the blatant racist actions of the citizens is due to the fact that, in 1967, there was not one Black family in residence in Culver City.”[xliii]

The Culver City Police – More Recently

One of the more recent controversies involving the Culver City police occurred in 1994, when they hired Tim Wind.

He was considered “one of the most unemployable cops in the country,”[xliv] as millions of Americans had seen footage of him kicking and beating Rodney King - an act that led to his termination by the Los Angeles Police Department.

Despite being “vilified as a symbol of racist policing,”[xlv] Culver City’s Chief of Police, Ted Cooke, hired Wind as a community service officer. When the decision was reviewed by the City Council, despite “more than 700 signatures on a petition to have Wind fired” and “emotional protests by a stream of residents,” the council “voted unanimously to endorse Cooke’s controversial hire.”

In the wake of the Wind controversy, the L.A. Weekly conducted a major investigation into the Culver City Police Department, which they published in September 1998. They described Chief Cooke as “a lawman who dominates Culver City like the sheriff of a small county in the Deep South,” and examined nonwhite experiences in the city. Among other things they reported

Many blacks and Latinos, especially youth, say they live under constant police surveillance, and believe they are being targeted. Victor Barraza, an 18-year-old Hispanic graduate of Culver High School, who ran track and played on the basketball team, says he has been pulled over four times by the Culver City police in the last year alone. On one occasion, he says, he was told by officers that a stolen car matched his car's description. Another explanation was a cross hanging from his rear-view mirror. Other times he was given no reason, but said his car was pulled over, he was searched and his identification examined. Not once, he says, did he receive a citation.[xlvi]

L.A. Weekly also spoke with Carlos Valverde, then 25 and a new Spanish teacher at Culver City High School, who today has his doctorate, teaches English, and is the school’s Director of Student Activities. He had filed a complaint with the Culver City Police Department after being pulled over and told the newspaper, “What’s interesting is they never cite you for it. They search you, search the car, and then they end up letting you go… And then, the classic phrase, 'Hey, today is your lucky day.’”[xlvii]

In addition, they revealed that the Culver City police were continuing to hog-tie suspects’ feet to their hands behind their back as a method of control, even after it was banned in other police departments. Further, they reported the L.A. County Coroner’s Office had not only concluded that hog-ties by Culver City police “led to the deaths” of two suspects but had declared them homicides. Both suspects were nonwhite. No charges were filed against the police in either case.[xlviii]

Gary Silbiger, a member of the Culver City Community Network, commented at the time to L.A. Weekly.

We have an Arts Committee, a Human Services Commission, a Planning Commission but no Police Oversight Committee – we have a City Council that's completely uninterested… The City Council feels Cooke is just too powerful, and they don't want to risk their political careers. The police get a huge amount of the budget, and our schools and libraries need money.[xlix]

Cooke remained Culver City’s Chief until he quietly retired in November, 2003, after 27 years on the job.

The Los Angeles Times noted at the time,

He remained the only police chief in Los Angeles County to deny the district attorney access to departmental investigations of officer-involved shootings. Every police department in the county has agreed to notify the D.A.'s office whenever a police shooting occurs -- except for Culver City's.[l]

Confronting Our Past

Culver City’s history is filled with racist incidents too numerous for this one article. Here are two more, briefly:

- During the 1950s, William Bailey, a black World War II vet and science teacher, and his wife barely escaped when their house was bombed shortly after he moved into a white Culver City neighborhood.[li]

- In 1991, during the first Gulf War, then-Culver City Mayor Steven Gourley created controversy in his State of the City address by calling for the closing of the U.S. borders to undocumented immigrants. “If George Bush wants to draw a line in the sand, he should draw a line between Tijuana and San Diego, not just between Iraq and Kuwait.”[lii]

And there is even more to learn about the town’s history – such as how its white supremacist past impacted the schools, neighborhoods, and workforce. Or how this past is reflected in the City’s institutions today.

All of this, of course, creates a terrible legacy. As Andrea Gibbons observes in her excellent book on the history of housing segregation in Los Angeles, “Land is in fact a place where economics and ideologies come together, and where an intensely racist past lives on forcefully into our present.”

She reveals that “shocking inequalities in wealth – much of it grounded in the homes people own – continue to haunt Angelenos: Mexicans have a median wealth of $3,500, African Americans of $4,000, and whites of $355,000.”[liii]

Loewen’s book has been reissued with a new preface where he observes, “Most former sundown towns have never admitted their racism.”[liv] This certainly applies to Culver City, although there have been individuals and coalitions fighting to expose this history and change structural practices for decades. This work is in no small part responsible for the recent installation of a new, more progressive city council and the city’s first black council member. As a result, at this particular moment, there appears to be an opportunity to make the next 100 years qualitatively better than the first – for all, not just some, of those who wish to enjoy the city’s quality of life.

If the city were to admit its own harsh truth, it would be an important step forward as we continue to look for ways to undo the harm.

There is much work to do.

John Kent is an Annapolis graduate, ex-Navy officer, fighter pilot and Vietnam veteran who opposed the war and has been fighting for justice ever since. He lives in Culver City and works as a computer programmer.

Notes

[i] Loewen, James W., Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, Touchstone, 2005, p. 3.

[ii] Lytle Hernández. Kelly, City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles 1771 – 1965, The University of North Carolina Press, 2017, p. 164.

[iii] Maher, Adrian, “Culver City Confidential”, LA Weekly, Sep 9, 1998, p. 6.

[iv] Rasmussen, Cecilia, “Klan’s Tentacles Once Extended to Southland”, Los Angeles Times, May 30, 1999.

[v] Los Angeles Herald, Volume XLI, Number 113, 12 March 1915, p. 4.

[vi] Rudwick, Elliott M. and Meier, August, “Black Man in the ‘White City’: Negroes and the Columbian Exposition, 1893”, Phylon Vol. 26, No. 4, 1965, p. 354, Clark Atlanta University, quoting from the Cleveland Gazette.

[vii] Valance, Hélène, “Dark City, White City: Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition, 1893”, Caliban, 2009.

[viii] Los Angeles Herald, Volume XL, Number 41, 19 December 1913, p. 7.

[ix] Los Angeles Herald, “Realty Salesmen to Give Minstrel Show for Church”, Volume XL, Number 276, 19 September 1914, p. 11.

[x] Los Angeles Times, Jul 27, 1913, p. v1.

[xi] Rothstein, Richard, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017, p. 59.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] The Color of Law, p. 62.

[xiv] Weiss, Marc A., The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning, 1987, p. 122

[xv] Gibbons, Andrea, City of Segregation: 100 Years of Struggle for Housing in Los Angeles, Verso, 2018, p. 26.

[xvi] Kurashige, Scott, The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles, Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 237.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Sides, Josh, L.A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present, University of California Press, 2003, p.121.

[xix] Ibid., pp. 17-18.

[xx] Ibid., pp. 18.

[xxi] Gibbons, p.25.

[xxii] Redford, Laura, The Promise and Principles of Real Estate Development in an American Metropolis: Los Angeles 1903-1923, dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2014. p. 102.

[xxiii] California Eagle, Nov 18, 1943 p. 1.

[xxiv] The Color of Law, p.82.

[xxv] California Eagle, Nov 18, 1943 p. 1-2.

[xxvi] Parson, Donald Craig, Making a Better World: Public Housing, the Red Scare, and the Direction of Modern Los Angeles, University of Minnesota Press, 2005, pp. 57-58.

[xxvii] “Klan’s Tentacles”.

[xxviii] “Jurists Belong to Ku Klux, Claim”, Los Angeles Evening Herald, July 20, 1921

[xxix] Rice, Tom, White Robes, Silver Screens: Movies and the Making of the Ku Klux Klan, Indiana University Press, 2016, pp. xviii & 81.

[xxx] White Robes, p. xvii.

[xxxi] Wikipedia, “Ku Klux Klan raid (Inglewood)”.

[xxxii] White Robes, p. 81.

[xxxiii] Moss, Marilyn Ann, Giant: George Stevens, a Life on Film, University of Wisconsin Press, p. 14.

[xxxiv] White Robes, p. 81.

[xxxv] Gnerre, Sam, “The 1922 Ku Klux Klan Inglewood Raid”, Daily Breeze Blog, Mar 15, 2014, http://blogs.dailybreeze.com/history/2014/03/15/the-1922-ku-klux-klan-inglewood-raid.

[xxxvi] California Eagle, Jun 20, 1940. p. 2.

[xxxvii] City of Inmates, p. 164.

[xxxviii] California Eagle, Jan 1, 1948, p. 18.

[xxxix] California Eagle, Dec 14, 1950, p. 1-2.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Mitchell, Marsha, Los Angeles Sentinel, “James Forte--Pioneer with Culver City Police, Fire Dept”, Feb 21, 1991, p. A3.

[xliv] LA Weekly, “Culver City Confidential”, Sep 9, 1998, p. 1.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] “Culver City Confidential”, Sep 9, 1998, p. 6.

[xlvii] Ibid.

[xlviii] Ibid., pp. 7-8.

[xlix] Ibid., Part 2, p. 1.

[l] Renaud, Jean-Paul, Los Angeles Times, “Police Chief Leaves Job as Quietly as He Served”, Dec 22, 2003.

[li] Lewis, Andy, Hollywood Reporter, “L.A.’s Ugly Jim Crow History: Nat King Cole’s Dog Poisoned in Hancock Park”, Feb 19, 2015.

[lii] Koh, Barbara, Los Angeles Times, “Close the U.S. Border, Mayor Says”, March 28, 1991.

[liii] City of Segregation, pp. 6 & 1.

[liv] Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, James W. Loewen, The New Press, Reprint, Jul 17, 2018