Older adults are mobility challenged. More than 20 percent of those 65 and older, according to a Rand study, do not or no longer drive. Those who do drive go shorter distances, are fearful of driving at night, have difficulties with daytime glare, and hesitate to drive on freeways or other higher speed roadways. Once they turn 70, on average they will have 11 more years in which they will still be able to drive.

However, as the population of older adults increases, more seniors are driving cars, as many as 14 percent of California residents. Moreover, in the next 20 years, the senior driving population is expected to rise to 23 percent in California, while the number of seniors who drive nationally could reach as high as 25 percent by 2025. Older adults get into car collisions at a rate 16 percent higher than those aged 25-64, while younger drivers under age 25 have a 188 percent higher rate than seniors. When car collisions do occur, older adults may experience significant harm, including serious bodily injury and a higher fatality rate.

Older adults are also transit users. There are a number of programs and incentives to encourage senior transit use, including reduced fares, wheelchair access, and driver training (for example, to encourage bus drivers to make stops close to the curb.) Many older adults with disabilities require assistance and utilize paratransit services, such as Dial-A-Ride programs mandated by the 1990 American Disabilities Act.

Yet transit use presents a number of concerns and barriers for seniors. To board a bus or rail line represents a risk factor, especially if the bus or train begins to move before the person finds a seat. To ascend the bus from the curb may present difficulties, while the descent could be hazardous when a bus stops several inches from the curb. At the same time, paratransit programs that many seniors utilize are generally the least efficient forms of transit. They may be overcrowded and difficult to meet a schedule, such as for a medical appointment. Yet they are necessary for those who otherwise may not be able to access transportation.

Older adults may walk or bike to get places and can benefit from the exercise. Depending on the sidewalk or street, there may be a calmness and meditative aspect to the walk or ride. Yet walking and biking barriers for older adults are numerous and often discouraging to the point of eliminating the option for many. Poorly maintained sidewalks are especially hazardous to older adults who can experience significant risk if they were to slip and fall, including if they needed to walk to a transit stop. Sidewalk cracks, potholes in the streets, short crosswalk times not amenable to the amount of time an older adult might require to cross an intersection, are among the many barriers that still exist.

Given these barriers and an absence of options, a lack of mobility for seniors creates major quality of life concerns. Without effective transportation, older adults miss medical appointments, as many as 3.6 million annually. They become socially isolated and live alone; 42 percent in Los Angeles County do so. Loneliness for older adults is a powerful negative subjective experience and the combination of social isolation and loneliness in turn can lead to declining health outcomes, including higher blood pressure, higher incidence of flu, and an earlier onset of dementia.

Senior advocates argue that increasing mobility for older adults is an important way to help improve their health and quality of life. The search for a transportation strategy for seniors has led advocacy groups such as AARP to explore most recently the use of ride-hail or transportation network companies (TNCs) such as Lyft and Uber. Lyft and Uber in turn have looked to the health sector as a possible area for revenue expansion as well as for its public relations benefits. Local governments have also begun to explore a senior-TNC linkage, motivated, in part, to reduce the costs and inefficiencies of their required paratransit services.

I examined two of those new local government initiatives in Southern California, the city of Monrovia’s GoMonrovia and the city of Santa Monica’s MODE (Mobility On-Demand Everyday) programs, to identify whether and how a senior-TNC link might play out. I also looked at TNC efforts, particularly Lyft’s efforts in this area, as well as AARP’s activities, including a new AARP-Foundation funded USC study on the receptivity of seniors to utilize Lyft for appointments at the Keck Medical Center.

In both the Monrovia and Santa Monica programs, a desire to shift funds from expensive Dial-A-Ride services played an important role in developing their respective programs. The cost per van ride in the two cities averaged around $20-$25 per person. Monrovia utilized nine vans that served about 3,200 passengers monthly, including about 8 percent who were non-ambulatory or required assistance. However, Monrovia’s Dial-A-Ride service was also available to the general public (not just seniors) at a cost of $1/ride, while seniors paid 75 cents a ride. Santa Monica utilized six vans that averaged about 2,000 trips per month at 50 cents per ride. The Santa Monica rides were exclusively for seniors, with 10 percent of their riders non-ambulatory.

Both cities have transit options other than their van programs. There is one rail stop of the Gold Line in Monrovia and three stops of the Expo line in Santa Monica. Santa Monica’s Big Blue Bus system crosses multiple neighborhoods within the city as well as other areas including downtown Los Angeles and includes stops at the three Expo line stations. The Foothill Transit system serves Monrovia, with two of its bus lines including stops in Monrovia.

During 2017-2018, both cities began to search for lower cost alternatives to their Dial-A-Ride programs. Monrovia's program annually spent $1 million that was paid through various county transportation funds, including the 1980 L.A. County Proposition A half-cent sales tax that provided a portion of funds to local governments. More significantly, according to Monrovia City Manager Oliver Chi, new transit-oriented commercial and residential development involving more than 2000+ units near the Monrovia Gold Line stop had generated fears and anger about congestion and parking. City officials hoped that a partnership with a TNC could help in that regard.

The city launched GoMonrovia in March 2018 and soon touted it as the city’s own new primary transportation system. The program, according to Chi, immediately caught on -- more than 4,000 people participated in the first couple of weeks. GoMonrovia served destinations within or adjacent to the city. Fares were 50 cents, with the city subsidizing the rest of the cost that averaged $6 per ride. The city utilized its $1 million Dial-A-Ride budget and re-allocated $640,000 for Lyft rides, with the remainder for the Dial-A-Ride vans still needed since Lyft did not provide wheelchair access. In addition, Monrovia added a dockless bike share program through a partnership with Lime.

By the end of its first year, the city needed to make some modification to its program. Even after the city raised the cost of Dial-A-Ride to $1.25, all nine vans still needed to be in service at different times since there were as many as 3-4,000 continuing monthly van rides. By February 2019, Monrovia decided to limit Dial-A-Ride to only people with ADA requirements (e.g., requiring wheelchair access.) The Lyft ride costs also exceeded initial expectations since about 4-6,000 calls were made monthly through the “concierge” (call-in) service. Although 70,000 people had used the GoMonrovia Lyft service in its first 10-11 months, usage was slightly below the numbers anticipated.

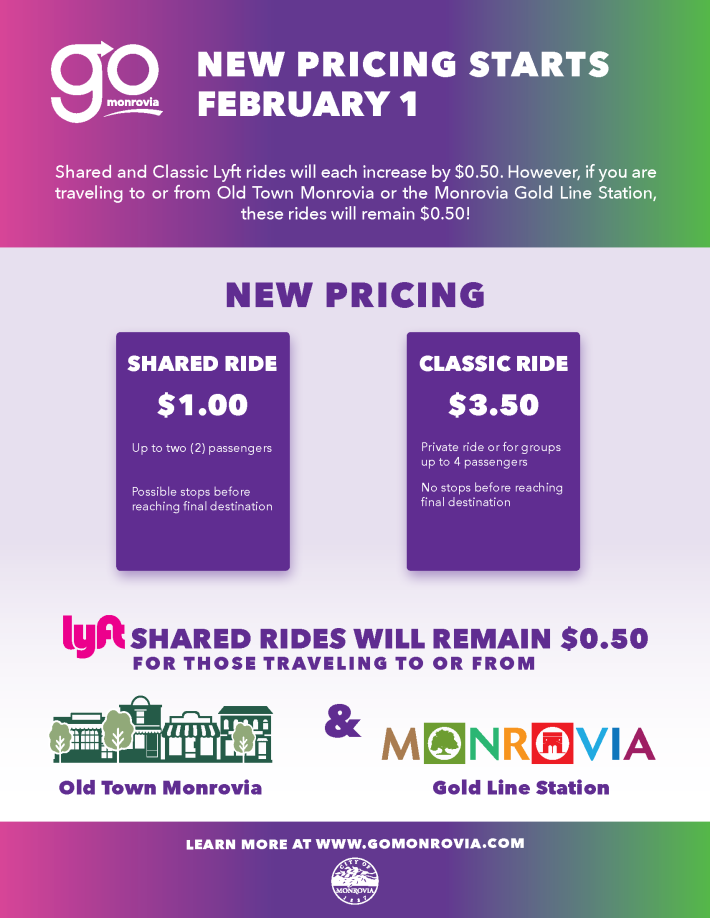

Given the van and concierge costs, the city then decided to change the Lyft ride fare for participants to $1/ride in February 2019, although it kept the fare at 50 cents for a ride to the Gold Line station. The $1/ride was for Lyft shared rides while the classic Lyft ride (about 20% of the total) cost $3.50/ride. At the same time, Lime scrapped the dockless bike share program in favor of its own national conversion from bikes to electric scooters. With these changes, and as it entered its second year, officials felt that GoMonrovia had become an important transportation program for the city. However, it did not as directly focus on the mobility needs for those 65 and older who represented 13.1 percent of the city’s population of 37,000.

Unlike Monrovia, Santa Monica designed its MODE program specifically as a “rebranded Dial-A-Ride program” to meet senior transportation needs. Prior to MODE during 2016-2017, 23,000 people used the Dial-A-Ride program, averaging 2.3 rides per hour per vehicle. To launch MODE, Santa Monica allocated $2.4 million -- $600,000 per year for four years (utilizing its Proposition A county transportation funds.) The city reduced its van service from six to two vans and selected Lyft through a review process. The Lyft rides would cost 50 cents and be available to anyone over 60 years old for destinations within the city of Santa Monica and to certain other destinations outside the city such as UCLA and the Kaiser West Los Angeles Medical Buildings. The city would also provide monthly orientation and sign up sessions to explain the program, including how to use the app and other aspects of MODE. Lyft would receive the full cost of the ride, since the city would subsidize the difference between the full fare and the 50 cents the MODE participant paid. Full ride cost has averaged about $4.25/person.

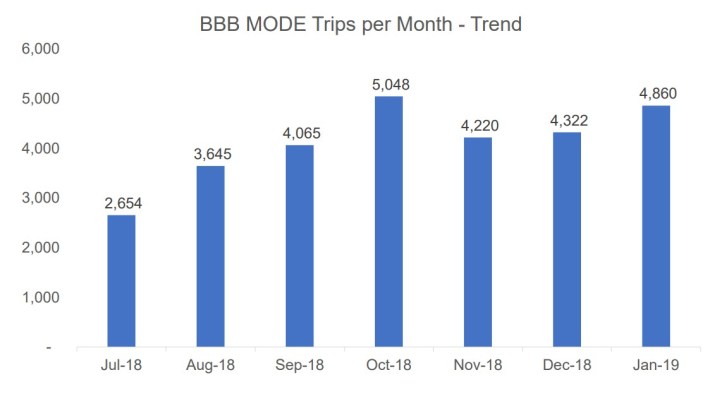

Santa Monica launched MODE in July 2018 as an extension of its Big Blue Bus system. This included the Lyft rides and a downsized Dial-A-Ride Van program. In addition, that summer, through an RFP process, Santa Monica granted four companies, including Lyft and Uber (as well as Lime and Bird) to operate their electric bike and scooter programs within the city. By February 2019, more than 1,500 people had joined the MODE program.

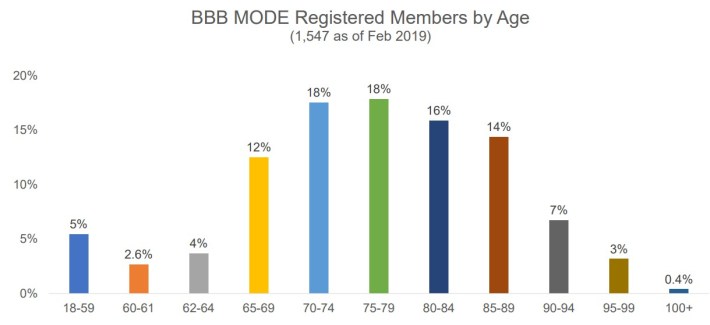

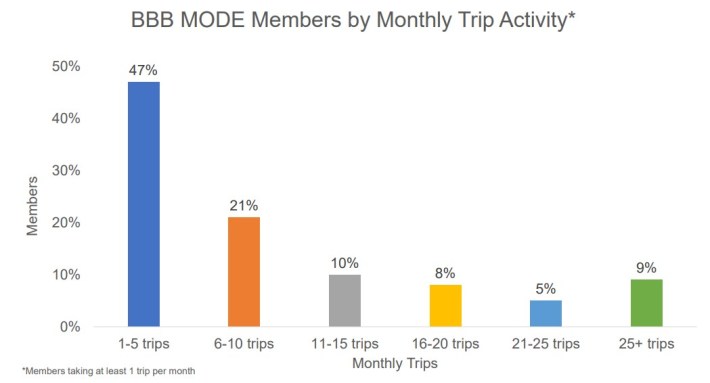

Among participants, 36 percent were in their 70s, and as many as 25 percent were 85 and older. Nearly half (47 percent) took between one and five Lyft rides per month, while a small yet significant (cost-wise) number (9 percent) took 25 or more trips per month. About 5 percent of the trips were outside Santa Monica.

Among MODE sign ups, 65 percent utilized the Lyft app for rides, 25 percent used a concierge/call-in service, and slightly less than 10 percent still utilized the mini-vans limited to people with full disabilities. The city's costs for Lyft rides initially averaged $6.50/ride but decreased to the $4.25/ride subsidy after three months when the program shifted exclusively to the Lyft shared ride. Prior to MODE, van rides had cost the city about $22/trip but that increased to $30/ride given the smaller number of vans and reduced cost efficiencies (fewer people using the vans). Combining the Lyft and van rides, the overall cost of the MODE program came to $11/trip.

Concerned about the costs exceeding future budgets if increases in participation continued to occur as anticipated, in March 2019 BBB officials began to circulate proposed changes. These included capping the monthly number of rides to 36, increasing the minimum enrollment age to 62, and raising fares for the Lyft ride to $1. Opportunities for reduced fares for low-income seniors would continue to be available through Metro’s “LIFE” (Low Income Fare is Easy) program. Despite requiring the changes and the grumbling by residents and some city officials about gig economy intrusions on city life (directed especially at the electric bike and scooter programs), the MODE program was seen as an important first step in increasing senior mobility for a constituency that represented more than 17 percent of the city’s 92,000 population. How it impacts and fits within the city’s overall transportation goals, however, remains to be seen (e.g., the need to reverse downward trends and increase Big Blue Bus ridership; reducing traffic congestion which had become a major residential complaint; and shifting away from car use and ownership.) Big Blue Bus ridership overall had a small loss of 1.1 percent in FY 2018 but that worsened the first two quarters of FY 2019 to 5.6 percent, in a period when TNC use (car rides, electric bikes and scooters, and the MODE program) was growing.

AARP, the USC Study and the Role and Impact of TNCs

At an orientation session for MODE that I attended in October 2018, most questions were directed at how the Lyft ride process would work, including how to use the Lyft app to insure that the MODE fare was being applied. The question of how and whether older adults are likely to use a TNC system has been the subject of a number of studies during the past few years, with varying results. This includes the USC Center for Body Computing study that received its $1 million grant from the AARP Foundation in 2018 through United Health Care.

For the past several years, the AARP Foundation has focused on social isolation and loneliness issues. According to AARP Foundation’s E.A. Casey, the organization continues to struggle to find effective solutions. One major concern involves lack of mobility that reinforces the isolation that nearly 20 percent of seniors over 65 experience. As part of this focus, AARP has been asking whether TNCs can work for seniors as a new type of transportation strategy and, if so, how to address barriers, such as unfamiliarity with the app and how to access rides.

The AARP Foundation had previously worked with the USC Center, whose research includes digital health-related issues. Through its grant, the USC Center undertook an evaluation of the ability of 150 Keck Medical Center chronic care patients between the ages of 60 and 92 to utilize a Lyft ride for any purpose, including for medical appointments at Keck. The average age of the study cohort was 71, while 46 percent lived alone. The group included low-income participants, many on Medicaid -- 50 percent earned $50,000 or less and only 10 percent earned over $75,000. Participants previously used a range of transportation methods to get to Keck, including the use of paratransit services, family members or caretakers driving them to Keck, some patients driving themselves, and a number who took public transit. People came to Keck from multiple locations and the average trip length was 14 miles. USC paid for the Lyft ride; the average cost for USC was about $20/ride or about $400 per participant for the nearly 5,000 rides taken during the three-month study period.

The study identified several key barriers participants identified to using a Lyft ride. These included lack of knowledge and unfamiliarity with how it worked, fear of an activity they had not previously tried, and concerns about the trustworthiness of the driver. USC provided training through a special video and a one-on-one intensive session with USC researchers. By the end of the three-month study period, research coordinator Rebecca Ebert reported that 81 percent of the participants had utilized the Lyft app, while the remaining 19 percent needed to use Lyft’s concierge/call in system. Nearly the entire participant group (99 percent) agreed to use the free (to them) Lyft ride. Among those, large percentages (97 percent) felt confidence once they used the app and many (90 percent) said they would be willing to use it again. 90 percent also felt it had improved their quality of life since they were able to utilize the ride for social purposes (e.g., visits to friends) as well as for medical appointments. There was also a 35 percent increase in exercise (as measured by Fitbit) although some low income residents had less exercise since they otherwise would have walked to transit.

For the AARP Foundation, the most important finding of the USC study was the successful training of participants in how to use the Lyft app - for participants not familiar with such technology. Earlier studies had indicated greater resistance to TNC use by older adults, so the high numbers (attributable in part to the intensive education and training provided) related to ability to access the app were welcome. The biggest concern raised by the study was the question of cost and sustainability. To subsidize such a program at a potential per-person cost of $1,600 annually (based on the USC study numbers) would require major funding, and whether that would have to come from public funding such as through Medicare-related sources. There were additional concerns about Lyft (or other TNC) drivers taking advantage of seniors less familiar with how the system worked by creating confusion about pick up locations and thus identifying a “no show,” a problem that Santa Monica also identified for its MODE users.

The AARP-Lyft relationship also points to other potential concerns. As Casey puts it, “for Lyft it’s a business relationship, they have shown no interest in understanding the older adult market.” Lyft, according to Casey, has not been proactive, other than interest in the publicity. They have largely resisted training with their drivers about older adult issues. While Lyft has shown an interest in tapping into the health market (as has Uber which successfully hired away Lyft’s lead person on the USC study as Uber also began to explore health-related market opportunities), that interest has not been linked as directly to facilitating senior mobility issues.

Lyft and Uber have both focused on the need to improve their image and to demonstrate social responsibility as part of their corporate profile; both companies emphasize what they call their commitment to sustainability by reducing car use. However, both Lyft and Uber operate in a profit-driven universe, an issue that will become magnified as both companies become public and need to be responsive to shareholders. Both companies have been operating with major losses since their own launch (Lyft in 2012 and Uber in 2009.) Lyft, in its public filing with the SEC, reported losses of $688 million in 2017 and $911 million in 2018 and stated that it might not achieve profitability any time soon, while Uber lost $1.8 billion in 2018.

Central to the sustainability claims of Lyft and Uber is that people who use TNCs have reduced their car use; in its SEC filing, Lyft in fact argued that nearly half of Lyft riders used their car less. However, other studies have either contradicted or put in context those claims. A UC Davis study noted, for example, that those they surveyed who used their cars less simply substituted TNC use for their car ride, thus potentially not decreasing overall vehicle miles traveled by car. The impact on transit use also indicates that the use of TNCs reduces and may even substitute for transit use. In addition, while TNC use has potentially influenced those under 30 to postpone the purchase of a car, the numbers of all age groups of those deciding to give up their car with the availability of TNCs is only 9 percent according to the Davis study. Moreover, those over 65 have been a miniscule percentage of TNC users, just 3-4 percent of all age groups.

Despite the incessant push to develop new riders and new sources of revenue by the TNCs, as reflected for example in Lyft’s SEC filing, seniors have not become a focus of their outreach and marketing. While Lyft has touted GoMonrovia, for example, the program has been heralded as a suburban partnership (suburban riders representing a key TNC target for expansion), not as a program benefiting seniors. Lyft has been more engaged in Santa Monica with its electric bike and scooter opportunities than the MODE partnership. The TNCs, furthermore, have shied away from addressing the specific needs of older adults, whether driver training, special accommodations such as wheelchair access, or an interpretation of design and mobility management that is people-centered rather than just technology-driven. The AARP board of directors recently approved a series of policy guidelines based on an AARP research report about the need for universal mobility as a service to meet public goals, including those for senior mobility. This contrasts with the TNC argument that they do represent a type of mobility service, but it is one where the TNC ride remains central and where their mobility service role drives the search for expanding profit centers and market dominance.

For Santa Monica and Monrovia, the economics of the program, similar to the findings of the USC study, are likely to depend entirely on future public sources of funding, if these kinds of programs are to be sustained over time. While there are potential advantages of a ride-hail service for seniors, such service needs to supplement and not substitute for other modes, including walking, public transit, or other forms of shared mobility. To make that happen requires new public policies, whether economic or regulatory or both, not just better technology where the range and specificity of people’s needs are not considered or are just an afterthought.

Like much else in the TNC universe, their “disruptive technology” potential to extend access, community need, and a right to service is too often subsumed by their focus on the technology providing, as in the case of transportation, a new and exciting (for them) major private profit center.

Robert Gottlieb is the author (with Simon Ng) of Global Cities: Urban Environments in Los Angeles, Hong Kong, and China. He is the founder and former executive director of the Urban & Environmental Policy Institute which helped organize the 2003 ArroyoFest event when the 110 (Pasadena Freeway) was closed for a bike ride and a walk ON the freeway!