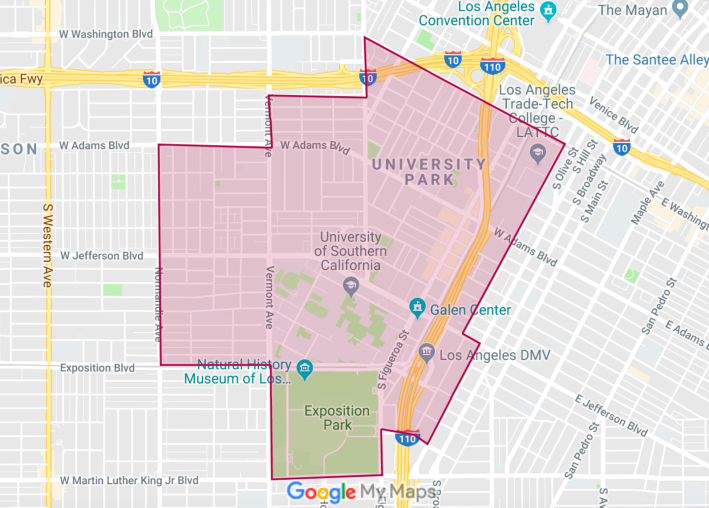

Although the University of Southern California (USC) recently instituted a certificate program aimed at improving law enforcement's ability to conduct community policing, its own public safety officers still appear to struggle on that front.

At least, depending on the community they're policing.

As Estuardo Mazariegos left his office just after 8 p.m. on February 11, he came upon a non-USC student handcuffed and seated on the curb next to his bike and other belongings.

His crime?

Riding without a light. [Find the video here, if it doesn't appear below. According to the officer conducting the stop, the man apparently asked to sit down because of a bad back.]

Mazariegos was upset to see someone dehumanized this way; he had grown up experiencing similar treatment from law enforcement. Particularly galling was that this wasn't even an LAPD stop - it was conducted by a private force on public streets well over a mile from the north end of the campus.

In between Mazariegos' comments, some of the exchange between the officer and the detained man can be heard. At one point, the officer asks the cuffed cyclist about outstanding warrants. When he hears the man has a felony warrant that had been dismissed, the officer says they're going to call the Southwest division and have them send someone out to check.

Then, in response to something the man asked regarding his probation officer, the officer says that they will call probation and that the next time the man goes in to visit his parole officer, he'll have to let them know he got stopped for this violation.

Stops as Surveillance

The man's parole status, of course, has nothing to do with his bike light situation, which is what makes these stops so insidious.

Were the stop truly out of concern for the man's well-being or were he a USC student, he might have been handed a flyer and educated about safety. That has been the practice of USC's Department of Public Safety (DPS) with students openly flouting the biking ban in the USC Village, where citation is considered "a last resort." [USC's Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the LAPD grants DPS officers the power to write parking, bike, and pedestrian citations and make arrests within the patrol area, when they have probable cause. They cannot cite motorists or initiate vehicle pursuits for any reason.]

Instead, this encounter reads more like a pretextual stop - a stop for a minor violation that gives an officer the chance to investigate an unrelated matter.

A common and highly questionable approach to crime suppression - LAPD's Metro division made the news recently for disproportionately targeting Black residents with pretextual stops in response to a surge in violent crime - it is also a tactic that generally backfires. The blatant criminalization of residents of color and potential for real abuses of authority tend to further erode trust between law enforcement and the community, making it that much more difficult for officers to enlist the community's help in addressing the crime they're trying to curb.

Yet, USC's public safety officers have a history of conducting precisely these kind of stops.

I first wrote in-depth about the harassment of area residents in 2013, after a friend who worked at a coffee shop serving USC students voiced frustration over being stopped and questioned while going back and forth to work every day.

Area youth had already considered getting hassled by either LAPD or DPS a "normal" part of growing up around the campus.

But in 2012, an on-campus shooting and an off-campus botched carjacking that left two graduate students dead changed USC's security calculus.

Where concern about spooking parents had previously meant that DPS kept a slightly lower profile, visibility now signaled vigilance.

Security fences were put up around the perimeter of the campus in early 2013 and it was made off-limits to non-students overnight.

Off campus, the introduction of more cameras, more license plate readers, stepped-up DPS patrols, and an additional 30 LAPD officers to conduct "high visibility" patrols and “more frequent parole checks on local gang members” made the community feel like it was being put under a microscope.

Black and brown youth now reported being stopped and forced to justify their presence in the neighborhood on the daily. Sometimes more than once a day. And sometimes it involved an unlawful search. It didn't matter whether they were on their way to school, sitting in their front yards, going to work, or running to the corner market for milk - they were fair game.

The LAPD's behavior was already troubling enough. With dash cameras having just been put in South L.A. cars to curb racial profiling, officers were doing what they could to get around turning the cameras on. Instead of getting out and conducting a full stop (instances in which they were expected to manually trigger the cameras), youth reported it was not unusual to have an officer pull up alongside them and harass them from inside the car. Officers almost always asked about parole status, I was told, and often aimed racist remarks at the youth or insulted their appearance.

But DPS, the youth maintained, treated them much worse.

Not endowed with all the powers of a full police force, DPS officers would assert their authority via intimidation. A 16-year-old reported he and his friend were handcuffed - a common complaint - to a neighbor's front gate and told that the officer didn't want to see them hanging out on their own street. A group of youth ranging from ages 14 to 16 spoke of a DPS officer who they say pulled up while they were chilling in their front yard, demanded to know what they were doing there, and said, “If the mailman can come up into your house to deliver the mail, then I can come that far up into your house.” Still other youth spoke of having their private parts jostled during invasive searches and of never being told why they were being detained. And if DPS decided to escalate the stop and call LAPD to run a warrant check or cite the youth, their detention could last for some time.

Of the approximately 50 male youth between ages 14 and 25 I interviewed over the course of a month and a half for that story, there was not a single one that had not had some kind of negative encounter with DPS, including kids who were hassled while waiting on campus for parents who worked there. And because DPS' sole purpose seemed to be to make them feel alienated in their own neighborhood, the harassment stung all that much more.

It sent the message that USC was not for people like them.

And it sent the message to USC students - who would see these stops as they walked or biked to and from campus - that their neighbors were a source of danger and not part of the USC community.

Or, at least, it sent that message to non-Black students.

Black students still reported having to dress in USC gear to avoid being harassed on and around campus.

At the time, DPS Chief John Thomas expressed great concern about the possibility that his officers were racially profiling youth in the community. He had grown up in South Central and had his own memories of being mistreated by law enforcement as a young man. And he remembered being discouraged from coming onto USC's campus to use the library by overzealous officers who made it clear they did not think he belonged there. He had joined the LAPD, and later DPS, in the hopes of changing the way his community was policed.

Aside from Chief Thomas, however, USC appeared to have little interest in hearing about the way the non-student population was being treated.

Questions about DPS' mandate or how their operations were being overseen were met with defensiveness or vague answers. I was even told by a white media relations representative that I needed to "broaden" my "circle" because he had never heard concerns about racial profiling raised in his "circle." The only clear answer offered regarding policing was the outright rebuttal of an LAPD officer's claim that USC officials had visited Southwest and requested officers engage in what essentially amounted to profiling.

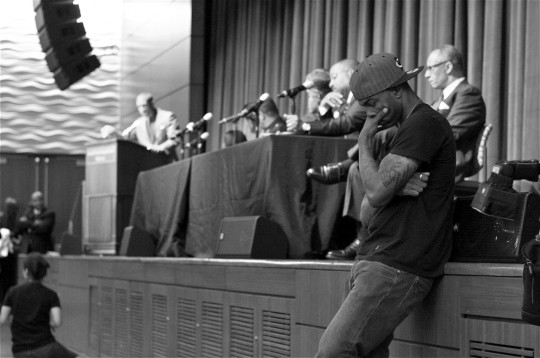

It took viral images of dozens of LAPD officers showing up in riot gear to shut down an end-of-the-year party thrown by Black students a few weeks later to get USC to engage more meaningfully on this issue. But even then, they only did so in regard to the students' claims.

Who Is Watching the Watchers?

Since that time, USC has committed to pursuing diversity and inclusion more broadly, including the creation of a Community Advisory Board (CAB) in 2016.

The purpose of the CAB, according to the Provost's office, was to "assess campus safety and profiling issues" and ensure that DPS held to both its plan to use California's Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA) of 2015 as a "guide to its practices in community policing" and its promise to "voluntarily to comply with measures that address race and identity."

Well-meaning as the launch of that effort may have been, it appears there has been little to show for all the fanfare.

For one, although Thomas had welcomed the formation of the CAB, they have only met with him twice (that he recalls) in the intervening years, leaving him to assume that there are no major issues with how the department is operating.

Even if the CAB were to meet regularly, it isn't clear that they would be of much assistance.

The two "community" members on it are involved in real estate and were chosen by the Provost. Neither are regularly on the ground or in contact with youth in the area. Which is not to say they couldn't have residents' best interests at heart - Danny Bakewell, Jr. (also Executive Editor of The L.A. Sentinel and L.A. Watts Times) has a long history of fighting for civil rights. But the twitter feed of South Pasadena's Mario Marrufo raises questions about why such an ardent fan of voices that peddle negative stereotypes about the Black community, and communities of color more generally, might be tapped to monitor discrimination.

It also is not clear what information the CAB would rely on to assess DPS' performance. The link on this outdated page to "Bias Reporting" - the only reference I could find to possible bias data - just takes you to an empty web page.

And while USC won't have to be in formal compliance with RIPA until 2023, it doesn't appear to have put in place any of the infrastructure necessary to properly capture, track, or assess that data to approach the voluntary compliance it aspires to in the meanwhile.

RIPA requires that officers collect data on the perceived race or ethnicity, gender, and approximate age of the person stopped, as well as other data, including the reason for the stop, whether a search was conducted, and the results of any such search.

It's a highly imperfect approach - relying on self-reported data and offering little in the way of information about how a stop was actually conducted or the power dynamics at play.

Knowing the race and gender of the person stopped, for example, would not tell you how they felt about being cuffed just for trying to get home. Or what kind of panic they might have experienced at the idea that, regardless of whether they had done anything wrong, the LAPD could be summoned or their parole impacted.

The data also wouldn't tell you whether the stop was truly justified. And because it is self-reported, it gives officers the incentive to leave out crucial information that might point to misconduct.

But even voluntary compliance with RIPA would at least provide USC a place from which to begin to oversee DPS.

One could look at the frequency with which cyclists are stopped for infractions like missing bike lights - something youth and men of color complain is regularly used by law enforcement to justify an unlawful stop and search - as a percentage of all stops, for example. Any patterns discerned in the logs could offer entry points for a deeper look into how the community is being engaged.

Assuming USC tightened up its present system for tracking stops, that is.

According to Chief Thomas, the best source of stop data is via call logs - the record made when officers first call dispatch and offer their location, a description of the person being stopped, and any other relevant information. Officers often fill out an interview card during the stop, as well, he said, although these are not always turned in at the end of a shift, and therefore offer a less complete record of the engagement.

Also of note is what appears to be the absence of any kind of mechanism by which even the most obvious breaks with policy are flagged.

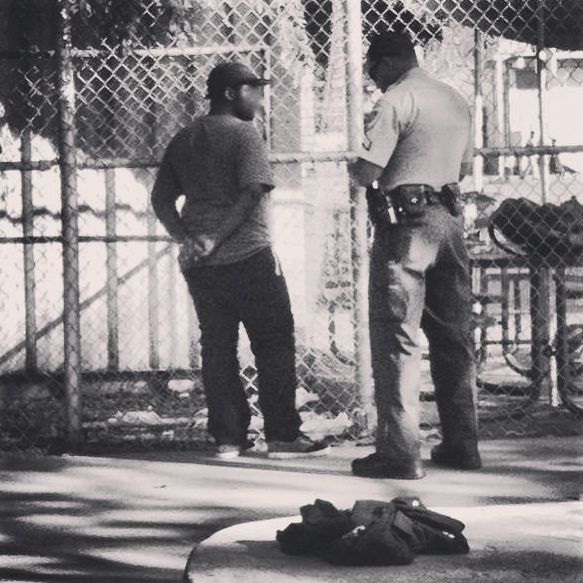

Chief Thomas was very troubled to learn, for example, that DPS officers were spotted with four Black youth up against a fence at Expo/Crenshaw back on November 20. If the stop was called in that night, no investigation was triggered into why half a dozen cars were posted up so far outside DPS' jurisdiction or how they got there, given that DPS is both prohibited from initiating pursuits and unable to safely conduct pursuits (their cars are not equipped with red and blue lights).

@USCDPSChief, a friend spotted 5 or 6 DPS vehicles @ the Expo/Crenshaw station yesterday evening & saw officers with four young black men put up against the fence. I couldn't find any reference to why DPS was so far outside its service area in the crime log. Can you help? Thanks!

— sahra (@sahrasulaiman) November 21, 2018

And because the chief hadn't seen my November tweets about the incident, nothing in the incident log from that evening suggests the young men stopped were involved in any of the reported crimes that evening, and none of the youth who were stopped filed a complaint, it's quite possible that it might have gone completely unnoticed if I hadn't called.

Which brings us to the crux of what is wrong with USC's passive approach to oversight and accountability: it banks on the community's silence.

Being a Good Neighbor Requires More than Good Intentions

Although profiling complaints like the one I made regarding the cyclist are immediately kicked up to the Office of Equity and Diversity (OED) for independent investigation, the burden still lies with those who are harassed or otherwise mistreated to initiate that process.

That requires that residents know who to complain to about DPS' actions or how.

Most don't.

And few are likely to complain, anyways, as those profiled are often young, fear retaliation, assume nothing will come of it, and/or are so accustomed to being stopped and harassed that they view it as "normal." [DPS does have a link to an online complaint form people can use on their "feedback" page and a way to report anonymously.]

And open as Chief Thomas is to talking to concerned community members about profiling - even giving them his own cellphone number to call should they encounter trouble with his officers - he is still part of an agency and institution that prioritizes its students over the larger community. If I - a reporter and an alum - can't get USC's OED to return my call, why would an area resident ever expect to be heard?

USC at least has the good fortune of having an experienced and candid chief in place who knows the community, cares about community relations, and understands that occasional implicit bias trainings - while valuable - aren't a substitute for lived experiences. He knows the unlearning of biases requires active practice, a better understanding of the history of the community and structural injustices, and more investment in opportunities for officers to get to know residents as people (e.g. via foot patrols).

But unless the university is willing to put the level of resources into building trust with the community that it has poured into beefing up its surveillance capabilities, things are unlikely to change much in that regard.

And given that USC's footprint has only continued to grow, unless it is willing to make a real investment in the infrastructure necessary to address accountability, things are only likely to get worse.

The university already boasts one of the largest campus forces in the country with over 300 employees, approximately 120 of whom are armed. It now sends new recruits through the police academy. And in order to be better able to respond to sexual assault cases and active shooters, it successfully lobbied for the modification of the California penal code in 2016 to allow qualified DPS officers to be deputized or appointed as a reserve deputy or peace officer (once the updated MOU with the LAPD is finalized). Chief Thomas even mentioned the potential for officers to be equipped with tasers and body cameras at some point down the line.

But officers appear to be aware they are no more likely to be monitored and held accountable for their actions than they were when I first complained about the treatment of youth of color six years ago. And judging by the handcuffs placed on the cyclist, they still view the non-student population as a threat.

Chief Thomas agreed this was troubling, but said he was still grateful for the call because of the investigations it would set in motion. Not just into the incident itself, he said, but also the department's current policies and practices. Sometimes, he said, “the only way that [the system] gets better, more accountable, and more transparent - I hate to say it - is if it’s made to.”

He also acknowledged addressing accountability won't be easy - the gap between what was relayed to dispatch and written up on the interview card and what was seen in the video of the handcuffed cyclist underscored the difficulty in monitoring profiling. But he was committed to continuing to push for the kinds of changes in the culture of policing that lead to these kinds of engagements, he said. And he hoped the community could be recruited to help with that process.

“I do want to talk to members of the community," he said. "I do want to know how they see us. I do want them to know we have ways to hold people accountable... And I do want community members being involved in some of the trainings.”

As far as the specific incident involving the cyclist, he said, he would have to wait for the Equity and Diversity office to conclude their investigation before he could begin his own. But he reiterated that he remained committed to helping USC be a good neighbor and ensuring his officers acted constitutionally and treated all University Park residents with the same courtesy and respect.

"I truly believe in accountability," he said.

***

For more on the history of security and policing around USC:

- January, 2013: How Far is Too Far?: Fortress USC and the Struggle to Keep Students Safe

- April, 2013: A Tale of Two Communities: New Security Measures at USC Intensify Profiling of Lower-Income Youth of Color

- May, 2013: A Tale of Two Communities, Part II: LAPD Finds it Stirred Up Hornets’ Nest by Profiling USC Students of Color