I had been vaguely aware of the Safe Park program and thought it was a good idea. But I got a crash course on it when I had to weigh whether or not it should go in to my church's parking lot. Our pastor had attended a meeting of Westside religious leaders held by Councilmember Mike Bonin’s office, which was looking to find new locations for Safe Park to expand.

I live next door to my church, so we were literally talking about the program taking place “In My Backyard.” I had no real issue with the concept, but wanted to know more before my wife and I gave our blessing for the project to go forward. Our pastor was clear he wouldn’t push the project without us, and, as you’ll see below, neither would Safe Parking L.A. (Safe Park).

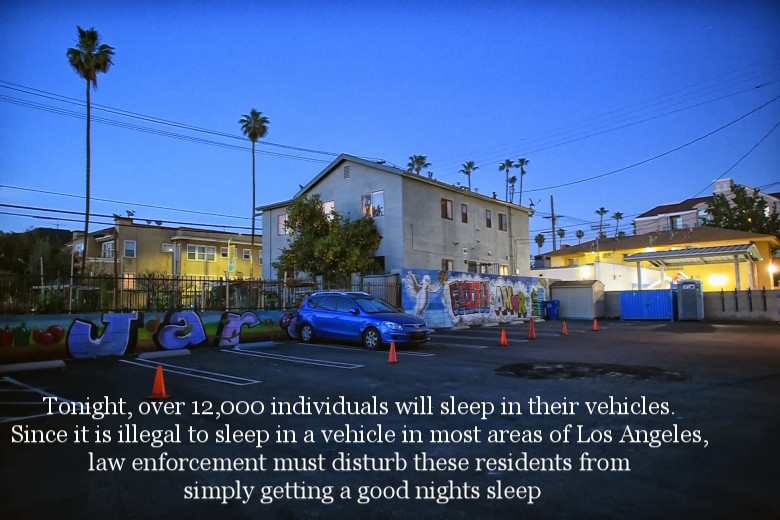

Safe Park is a nonprofit that is working with the City of Los Angeles to turn unused parking lots into safe spaces for people living in their cars to park, off public streets, for twelve hours a night. The program works with religious institutions whose lots remain empty for at least twelve hours every evening.

Given the outrage some communities in Koreatown and the Westside have shown towards the city’s proposed Bridge Housing programs, one would think Safe Park would be similarly controversial.

But, at least so far, that has not been the case.

“We’re one year in on our first project, and we haven’t heard a lot of pushback from the neighborhood,” explains Scott Sale, one of the three members of Safe Park’s Board.

Sale, along with Ira and Pat Cohen, were asked to look into whether or not a safe park program could work in los Angeles in 2010 by then-Councilmember Bill Rosendahl. Sale and the Cohens are members of Leo Baeck Temple, which is in Council District 5, next to Rosendahl’s district, but were asked to consider the program because the Temple had a large parking lot and members who were interested in helping the community. Leo Baeck Temple launched the city’s first Safe Park lot as a pilot in 2016. That program had to be closed down because of the Bel Air fire in December 2017.

Safe Park is based on the “New Beginnings” program in San Bernardino. New Beginnings does more than just work with the City of San Bernardino and community groups to provide a safe place for people to park; it also provides job opportunities, information about housing opportunities, and counseling and services. But it was their version of the safe park program that grabbed the attention of the Cohens. It seemed like such an easy solution to one of Los Angeles’ major problems, a relatively pain-free way to both provide a safe place for people experiencing homelessness to park, sleep, and relax and to remove cars, campers, and RVs from residential streets.

The number of people living in their cars in Los Angeles is high. Over 8,500 people slept in over 4,700 cars cars, RVs, trailers, or other types of vehicle, according to the 2017 Homeless Count. Yes, there are beds in homeless shelters available, but for many people owning a vehicle is an important part of their independence. Safe Park allows them to keep that as they transition back to permanent housing.

Today Safe Park operates in a parking lot at St. Mary’s Church in Koreatown, another in South Los Angeles, and a third at the Veteran’s Administration lot on the Westside. All three lots have the support of the local city councilmembers and community groups.

“We could have ten, or even a dozen, new lots open in a year, if we had the funding,” explained Ira Cohen when I visited the couple at their home. “We also want to expand the V.A. program to other veteran’s facilities around Southern California.”

At first I was perplexed. How much could it cost to open up a parking lot to homeless people?

“It’s more than that,” he said. “First, there’s a permit system. Second, there’s a security guard there for twelve hours, seven days a week, for an entire year. Third, there are often some things we need to do to make the space usable.”

The Cohens and Sale donate their time, but providing Safe Park's service is not free. The total cost comes to $100,000 a year. Safe Park L.A. gets grants from government agencies, community groups, and individual donors, but has not raised enough to support over a dozen lots a year and to pay for support staff. Safe Park also helps provide food, medical, health, and shower services for all of their participants. Most importantly, they also facilitate connections with local social service providers to ensure that their patrons are working towards getting housed and serviced.

“Funding is a problem,” Pat admits. Bigger than community opposition? “Oh yes, we don’t go into places where we’re not wanted.”

The Cohens explained the outreach process before a Safe Park lot would open. In the case of a church, the first step would be to meet with the local church council to explain the program and earn their support. If that step goes well, the next step is a more formal presentation for the entire congregation. From there, a third presentation for the neighborhood association or community council. If any of those three groups vote against having a Safe Park lot, the outreach ends and Safe Park moves on to find a different location.

“We want consensus,” Pat explains.

From there, assuming the funding is available, Safe Park begins to work with the city to identify people to participate in the program. Social service offices have lists of people that are good fits, who are currently living in their cars, hoping to move into permanent housing, and either looking for work or already partially employed. The city, social services and Safe Park will then work together to create a permit process for the number of vehicles that can fit in the lot. In most cases, the lot will be closed to the public and open to Safe Park from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. In some cases it might open a little later, but there will always be a twelve-hour minimum set aside for Safe Park.

If everything goes according to plan - if the community is on board, the funding is set, and the city is able to help pick people to participate in the program - then the lot can finally open. For the most part, the participants arrive in passenger cars, not often in RVs nor pulling large trailers. Passengers share space with their worldly possessions. At some point early in the evening, Meals on Wheels arrives with a dinner. But for the most part, the lot is quiet, with just the participants and the security guard present.

“This isn’t party time. It’s about letting people have a safe place to sleep and eat and get clean,” Ira explains. Cars without permits are not allowed in the lot. Similarly, participants aren’t allowed to have guests.

Nevertheless, participants seem thrilled with the program, telling reporters that Safe Park changed their lives by providing something as simple as a safe place to sleep. The existing lots are full, and waiting lists are not getting smaller.

For the record, my church was eliminated from consideration before we got to the outreach stages. Our parking lot faces into the community and is used by local groups, including the Boy Scouts, Angel City Chorale, community groups such as the Neighborhood Council, and many more, too late into the evening. That Safe Park can be picky is a sign that the program’s popularity is outpacing its funding. While that’s a good problem to have, it’s also a call to action for the city, county, and anyone interested in helping people have a safe place to rest at night.

This is the first in a three part series exploring Safe Park Los Angeles. This piece looks at the history of the program in Los Angeles. It will be followed by pieces examining the institutions and communities that house Safe Park programs, and another that talks to people participating in the program.