Monique López, the founder of the participatory planning and design firm Pueblo Planning, says she came to the field largely by accident.

In the first interview in an occasional series on practicing equity, she admits, “I didn’t know that planning was a career. Or a thing at all.”

Having grown up in a lower-income community of color in Imperial County where they “ate every night but lived month to month,” she hadn’t had cause to interact with the area’s planning apparatus until her community was targeted to be the site for a first-of-its-kind-in-California sludge incinerator.

Prior to that, she says, she hadn’t really been aware that she lived in an “EJ” (environmental justice) community or of what kinds of planning and resources went into sanctioning environmental injustices in communities like hers. But she knew enough to know the area was already plagued with high asthma rates and that an incinerator that would exacerbate existing air quality issues had no place there.

The three-and-a-half-years-long grassroots campaign she helped launch in support of the ballot initiative she co-wrote to both keep the sludge incinerator out of the area and prevent her community from having to face similar threats in the future would be her introduction to the world of planning.

Turns out it was not a pleasant one.

She quickly learned she was not valued as a community member. Beyond the general unfriendliness she experienced at the planning department, she says, staff often behaved as if they didn’t know what she was looking for because she wasn’t speaking proper planner-ese. As she got deeper into the campaign, she says, she began to understand more about how planning had systematically been used to legitimize unjust actions and perpetuate harms in communities like her own. It also became abundantly clear that the extent to which community voices had effectively been shut out of the process was what made it possible for such an unhappy status quo to endure.

When she accepted a scholarship to pursue a master’s in planning at the University of Oregon a few years later, it was to follow up on what she had observed - to explore how race and power differentials had been institutionalized in planning processes and, in turn, driven the form and feel of the built environment.

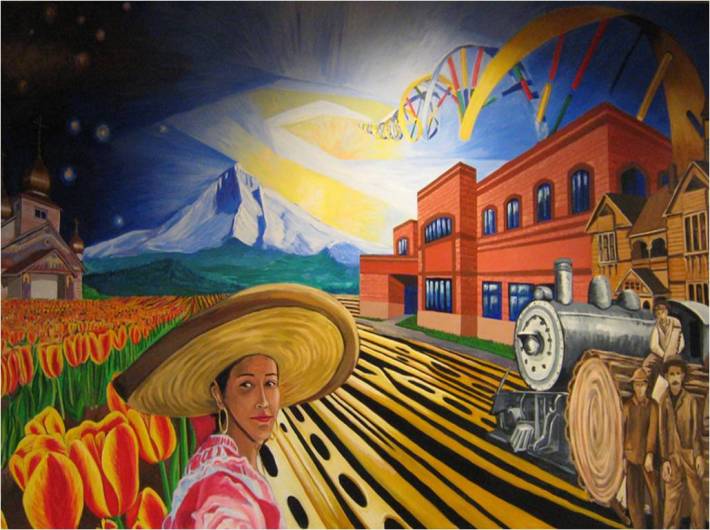

Her community was not the only place where race and power shaped practice. In the nearby town of Woodburn - where 60 percent of the 24,000 residents were Latino (the largest population of Latinos in Oregon) and the downtown business district was overwhelmingly Latino-owned - she studied the reluctance of the Anglo community to enact an ordinance that would pave the way for a mural celebrating immigrants’ contributions to the community. She found that while bright-colored murals depicting the immigrant experience were common on the interior walls of businesses and restaurants, the city saw allowing the public space to be more reflective of the diversity within the community as another thing entirely.

The Anglo and Latino populations had coexisted since Latinos had first arrived in the area in 1942 as part of the Bracero program. But “coexistence” had always been on white terms and in ways that reinforced whites’ hold on power.

Whether it was immigration raids in the 1970s, the refusal to build farmworker housing in the 1990s, or complaints about the raucous reds and greens with which the exteriors of Latino businesses were painted in the 2000s - the public space had always been carefully curated in ways that reminded the Latino community that the Anglos would be the ones who determined what constituted a proper public space and what kinds of identities could be expressed there.

The mural ordinance would eventually pass in 2012.

But in her interviews with residents in the lead-up to the vote, Monique often came up against what she described as a unique form of racism - one delivered with a smile and a side of pie. While some genuinely seemed unaware of how troubling their comments were, others appeared intent on discerning which members of the Latino community they could count on to see things the Anglo way.

A few even probed Monique’s loyalties, assuming that because she straddled two worlds - being of working-class Latino heritage and working on her second master’s degree - she would renounce one.

“You’re not one of those” kinds of Latinos, she was told by an Anglo woman who had sized her up as someone who would not be too radical and who would be able to see the problems inherent in handing too much power over to the Latino community.

But I am, Monique thought to herself even as she let the woman keep talking.

BUT I AM.

She says the incident served as yet another reminder of how important it was for her to remain mindful of the privilege that she has. Even though she comes from a low-income community, is a person of color, and is queer, she says, her education, marriage, and professional networks have all afforded her entry to privileged spaces that others without those advantages do not enjoy.

Her access doesn’t put her in a position to speak on behalf of others, she says, but it compels her to work to create space for those folks to be heard on their own terms.

It is also for this reason that, as a planner, she says, she is not interested in changing the city, per se.

Instead, what she cares about is using Pueblo Planning as a platform through which agencies and planners can revisit the process by which we plan change in the city.

While “inclusion” and “equity” might currently be all the rage, in practice, there are still too few voices from marginalized communities at the table. Because of their smaller numbers, those that are present are more likely to be questioned, more easily pushed aside, more likely to be get burned out from the barrage of micro and macroaggressions they are subjected to by even the most well-meaning of colleagues, and more likely to feel isolated when privileged allies fail to be the accomplices their marginalized brethren need.

She has learned to navigate those spaces, she says. But breaking that cycle requires something more radical. “What about, ‘Let’s ditch the table!'" she says, "'Let’s go to the streets!’”

Being in the streets allows her to begin the way she did when she figured out how to uplift her own community a decade earlier: by asking what people need and aspire to; by tapping into sources of strength in the community and building on existing networks; by understanding both how the community defines a particular problem and where it fits within the larger context of their realities; and by acknowledging what is at stake for the parties involved if problems are resolved in particular ways.

This approach also allows her to fill a key niche. Too often, there is a sizable gulf in communication between even the most well-intentioned planning entities and disenfranchised communities. Valuable input can be lost because it doesn’t match particular pre-determined categories or it doesn’t fit within the way a problem is being defined by planners. Or there is very little community input to work with because the combination of the historic lack of trust and the siloing of the problem reinforces the community’s belief that the city doesn’t have residents’ greater well-being at heart.

Monique’s background makes it easier for her to know what to listen for in disenfranchised communities, taking the burden of having to know planner-speak off stakeholders’ shoulders. And her training means she can also translate what she hears - including important contextual information - into frameworks planners can then use to shape the design of a project.

She was able to serve as that bridge in a way that helped a San Diego community get the regional planning agency to revisit its freeway expansion plans and consider one of the alternatives it had originally discarded. She was also able to synthesize the data gathered by local community-based organizations working along the Blue Line rail line in South Central and help translate it into concrete equity-centered asks for Metro’s first-of-its-kind First Mile/Last Mile plan for the corridor. And, as we’ll see in next week’s installment of this series, she was able to work with street vendors in MacArthur Park to design a set of configurations for the vending district that might better serve the needs of the vendors there.

Communities are ecosystems, Monique reiterates. Planning must move beyond its preference for silos and transactional relationships if it is to help these ecosystems thrive.

At the end of the day, doing so might not change much with regard to a final output, she acknowledges. A crosswalk or bike lane may still be implemented the way it was originally designed. But being intentional about the process will, at the very least, help planners avoid perpetuating the harms caused by past discriminatory practices and should help keep them from inflicting new harms. Moreover, she says, the same tools that embedded generations’ worth of structural racism in the built environment, if part of an inclusive and respectful process, can also be repurposed to dismantle it.

Because it is so hard for larger bureaucracies to do that kind of reorientation on their own, Monique hopes that Pueblo will be called upon not only to help lead the way as a consultant, but also as a resource for local stakeholders seeking to make planning work for them and their communities. She’s still figuring out how Pueblo’s social enterprise model will work, she says, but she is confident that she has positioned herself exactly where she is needed most.

“I’m hopeful,” she says, regarding the potential for change in the planning landscape. “Once you change the city planning process...you're going to change the city in a manner that's more equitable, that's more sustainable, that's more human, and that's more just. It starts with the process.”

Listen to my full conversation with Monique below or here. In it, she goes more in-depth regarding her background, what she thinks about while navigating uncomfortable situations, more on the how she approached the practice of equity in the specific projects she's worked on, and more about Pueblo. Next week's interview will be more of a case study of how she centered equity and put all the principles discussed here into practice in her work with street vendors in MacArthur Park.

[Please forgive the uneven sound and utter lack of pleasantries - this was my first foray into recording and I forgot to both be more ceremonious and ensure the mic also picked me up.]