As we watched the bikes line up in the parking lot at Ted Watkins Park at 103rd and Central in Watts for the Los Ryderz' anniversary bike ride this past Saturday, Javier "JP" Partida explained why he had demoted one of his club members.

He had seen the young man being disrespectful and dramatic on social media and warned him to cut it out, he said.

He voiced concern about how the young man's behavior might reflect on the club - a project Partida had launched six years earlier to uplift at-risk high school-aged youth through a combination of cycling, mentorship, leadership training, and community engagement. The club had worked hard to build relationships and trust with the community over that time and to prove to both the community and the youth themselves that the youth had something positive to offer Watts, regardless of what their past may have entailed.

Although it went unspoken, Partida's real concern seemed to lay with what the young man's behavior would mean for all the progress he had made. The young man had been with the club for several years and had risen quickly through the ranks, turning his life almost completely around in the process. There were occasional setbacks, but Partida had kept on top of him, always helping him find his way back. This time, the young man seemed to be spiraling. So, when repeated warnings didn't result in a behavior change, Partida demoted him.

It was a significant blow.

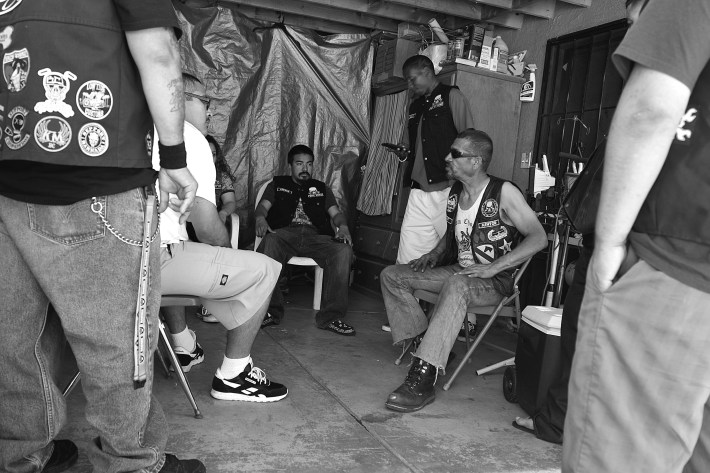

The bike clubs in the area have long borrowed from motorcycle clubs - of which there are a few in South Central - with regard to their hierarchical structure, the titles members can earn, and even the use of probationary periods to determine how committed new recruits are and how well they fit in with the club's ethos.

In Partida's case, the clear expectations and roles he laid out were tied to his approach to mentorship. He gave the youth much-needed structure while helping them see they could achieve their goals if they were willing to put in the work.

The youth needed that push.

The ones he had recruited for the club all had huge hearts but often struggled to stay on track because of how their backgrounds occasionally tripped them up. Some were former gang-bangers. Others had been in and out of trouble with the law or kicked out of at least one school. Others struggled with family problems, domestic violence, substance abuse-related problems, mental health issues, and/or making ends meet. Almost all had low self-esteem or were plagued by self-doubt. Few believed they had something of value to offer and fewer still had had a true mentor in their lives that stuck with them through the ups as well as the downs.

At club meetings - held regularly back when the club had a meeting space at the Watts Civic Center - members were encouraged to step up and take leadership roles.

And the ceremony with which titles were announced during meetings - usually accompanied by an official commendation, a few words about what the youth had done to earn their promotion, goody bags, and cheers from the recipient's peers - could make receiving a title feel like a kind of graduation to a next level of personal growth.

Watching each other rise through the ranks brought the youth closer together - they supported one another's journeys, lifted each other up when things got tough, held each other accountable when some slipped back into their old ways, and refrained from judging each other.

They proudly displayed their titles on their club vests - making that the way clubs from around South Central and beyond would come to know them.

Some presented their certificates of achievement to potential employers as evidence of how prepared they were to take on the responsibilities of a new job. Others wrote about what they accomplished with the group on application essays for school.

It was therefore by design that a demotion would be no small matter.

And while he knew it would hurt the young man to feel like he'd fallen from grace, Partida trusted that the combination of the years invested in steering the young man straight and the weight of the community's high hopes and love would push him to make better choices going forward.

It's tough love, to be sure. But the love couldn't be more genuine, and the members of the club have always known it.

Even as the club approached its third anniversary in 2015, the youth were hyper-aware of just how much of himself Partida had invested in them. They had been stunned to learn he wasn't paid to run the club. And most had gotten misty-eyed when asked for their thoughts about him, shaking their heads and speaking in unfinished sentences - "If it weren’t for JP…,” "Who knows what I’d be doin’,” "I don’t know where I’d be,” and "He’s like a second father – the father I never had."

Despite how much the club meant to the youth, active club membership would dwindle significantly within a year.

The members hadn't lost interest.

Rather, Partida had done his job too well - the youth were graduating high school and going on to college or getting real jobs, leaving the older youth (now in their early 20s, some of them parents themselves) to carry the torch forward.

Other factors intervened, too

Partida had a long bout with cancer, treatment for which left him unable to organize rides for many months.

He also lost access to the space at the Watts Civic Center where the youth had been able to break bread together after rides and where he had been storing the bikes (many of the youth could not afford their own bikes), tools, and other things that helped the club keep rolling. Not having a space also meant he was not able to continue teaching the youth to design, build, and maintain their own custom bikes - an activity that kept them busy, helped them learn how to take direction and problem solve, gave them marketable skills, and gave them something to be proud of.

The club was officially adrift.

Seeking a new way forward, Partida has spent the last couple of years working more closely with Art "the Skrapfather" Ramírez, a long-time freelance welder best known to Angelenos for his insanely detailed chopper bikes.

Ramírez has been known to creatively weld anything from custom artistic bikes for Burning Man to sturdy custom bikes for street vendors to churro makers and whatever else needs fixing at the swap meet around the corner from where he lives. Most notably, Ramírez and Partida had built a vending cart for elotero Benjamín Ramírez, who was assaulted by an Argentinian named Carlos Haka while vending in the Hollywood area (an act of generosity that helped earn them a Streetsie Award).

While continuing the work of passing on these skills to club members at Ramírez' "skrapyard" (the driveway outside his back door), Partida and Ramírez also continue to ruminate on the number of youth they could reach and the kinds of projects they could be engaged in if they could finally get hold of a permanent space for the club.

But space is hard to come by in the 'hood.

Not because spaces don't exist - on the contrary, there is an abundance. But there is an abundance of storefronts and underused spaces because folks can't afford to access them.

To be fair, that's a problem a lot of collectives face, regardless of who or where in the city they are - space is never cheap. But it's an issue that is particularly acute for residents trying to uplift their neighbors in disenfranchised communities.

As we detailed in club member Slimm's story last week, the cumulative legacies of disenfranchisement, denial of opportunity, and repressive policing in communities like South Central have conspired to make the public space inaccessible, particularly for black and brown youth. Which means that the work of community-building has to be done not only in private spaces, but in spaces that those youth can actually get to.

In Watts, where more than two dozen gangs claim just about every inch of sidewalk within a 2-mile radius, finding a space that those without access to a car could safely walk, bike, or take transit to is no small task.

Keeping the space is another matter entirely.

Rents can be steep and, as the East Side Riders found after investing months in getting their co-op/shop ready to open on Central Avenue, co-ops are not always self-sustaining where residents have little disposable income, even if the shops have a for-profit component. And break-ins can sink an endeavor before it even has a chance to get its head above water.

While Partida is contemplating formalizing his status as a non-profit so he can receive grants to keep the club afloat, the reality is that grants tied to cycling tend to pay for pop-up activations, the teaching of cycling skills, engagement efforts around particular projects, or awareness campaigns aimed at spreading the gospel of walking, cycling, and safety within specific time windows. They tend not to support the kinds of operating expenses Partida would seek to have covered.

And to access those grants at all, applicants generally have to know how to put together a proposal, use the right jargon, and be able to produce a report detailing measurable outputs.

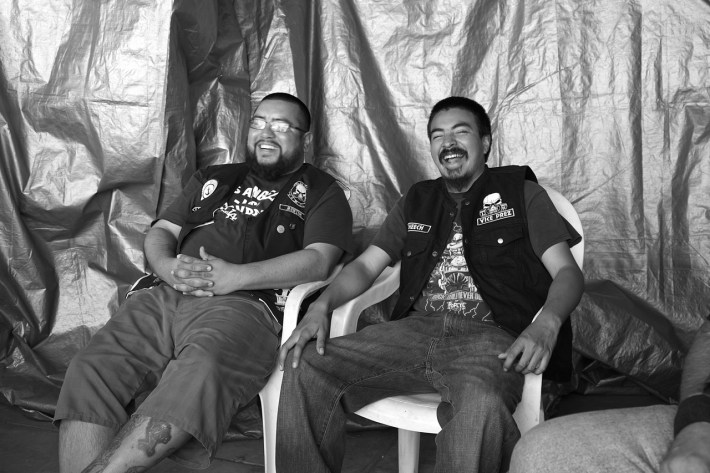

There's just no way to measure what being part of the club has meant to young men like Cheech (at right, above), who found himself having to shoulder the responsibility of providing for his family after the sudden loss of his father a few years ago. Or for Slimm, profiled here, who had spent most of his teens in jail and who, because of having lost his father as a child, didn't have the guidance and support he needed to stay straight until he got involved with the club. Or for William, who loves to laugh but who, at age 19, had openly voiced fears that there might be something wrong with him because of how desensitized he found he was to violence. Or for the family of Benjamin Torres, whose memory was kept alive and in the public consciousness by both Los Ryderz and the East Side Riders after Torres was killed in a hit-and-run in 2012. Or for Partida himself, who comes from the same kind of background as the young people he works with and who heals himself as he heals them.

Partida simply doesn't have the time or resources to figure out how these kinds of impacts fit into categories created to solve the problems people of privilege have imagined he and his community must have. Especially if any money received either would distract from or wouldn't support the mentorship and community-building work that is at the heart of what keeps the club rolling.

At the same time, the lease on the place where he currently stores the club's bikes will be up later this year, Partida says. Meaning that he probably can't outright eschew more traditional funding routes, either, regardless of how poor a fit they might be.

Whatever comes next, it is clear that letting the club lose momentum is not an option for Partida.

Pointing to a childhood friend's smiley seven-year-old son - a boy who had been bullied at school before joining the club - Partida reiterated that that was who he was doing this work for. That building a culture of community service meant bringing along even the younger youth and teaching them to turn sources of adversity into sources of strength.

The young man who had been demoted came up while Partida explained this and draped an arm around Partida's shoulders. Still in tough-love mode, Partida grumbled that it was rude to interrupt conversations that way.

Looking surprised and slightly sheepish, the youth apologized and said he hadn't meant to be rude, he was just trying to say hello. Then he stood there awkwardly for a moment, not sure what to say next. Getting back in Partida's good graces was going to take more work this time - Partida wasn't playing around.

But instead of getting defensive or packing up his bike and going home the way a younger version of himself might once have done, the young man rubbed the sleep out of his eyes. He'd worked the graveyard shift and was still in his uniform, having only gotten a brief nap in after work before dragging himself to the park to help road captain the ride.

The club was the young man's surrogate family. Being part of it had become part of his identity. And the group was about to take to the streets - meaning his family needed to be kept safe. He nodded, joked around with some of the other club members, then got on his bike and fell into formation.

Partida gave the signal and the ride rolled out.

Keep up with the work of Los Ryderz on their facebook page, here.