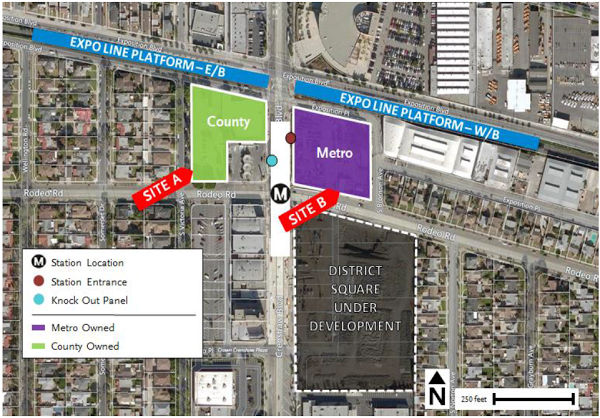

I should be focused on the content of the staff report regarding the mixed-use project proposal from WIP-A, LLC, a subsidiary of Watt Companies, for two Metro- and L.A. County-owned lots (below) at the South L.A. intersection of the Expo and (under-construction) Crenshaw/LAX Lines as part of Metro's joint development program.

There certainly is a lot to be said about it.

- Of the 492 residential units planned for the lots at the intersection of two rail lines - one of which was sold to South L.A. residents as their connection to jobs - only 73 (the minimum 15 percent required by Measure JJJ) will be designated as affordable. Those affordable units will be reserved for families earning under 50 percent of the area median income (families of four must earn $45,050 or less to qualify, but also earn a minimum of around $30,000 or approximately three times the proposed rent);

- The project will also feature 47,500 square feet of commercial and retail spaces, including restaurant spaces intended for locally-owned and operated businesses and a grocery store (Watt Companies owns the Slauson/Crenshaw and La Brea/Rodeo properties, both of which are home to a Ralphs grocery);

- The project will feature open plazas, a bike hub, and car-share connections;

- And, in line with Metro's Transit-Oriented Development Guidelines, Watt would commit to having a business incubator-type space as well community-serving spaces.

And there is something to be said about the fact that, at a meeting of the Executive Management Committee this Thursday, staff will recommend Metro enter into a 6-month interim Exclusive Negotiation Agreement (ENA) with the developer before entering into the standard 18-month ENA.

A standard ENA gives the developer the space to further develop their plans, work out the terms of a Joint Development Agreement, work out ground leases with Metro, and pull together the appropriate construction documents before the project gets the full approval. The interim ENA would allow for Metro and the developer to communicate directly "about project scope and team composition, and to have an open dialogue with community stakeholders before committing to a long term ENA," according to the staff report. It would also require the developer "to identify and enter into a letter of intent with a community-based organization for its participation in the development of the project, including the opportunity for an economic interest" during the first three months of the ENA period. [Scroll down for full text of the report.]

The more prevalent use of the interim ENA option is thanks, in great part, to the uproar over way Metro tried to rush what appeared to be a gentrifying and non-community serving project for Mariachi Plaza through official channels without even a minimum of community engagement. The community, particularly some very activist youth and their mentors, demanded that Metro do better by communities.

At what will essentially serve as the gateway to the historic Crenshaw community, it is just as imperative that the community have a chance to engage the project and the developer as much as possible.

Truth be told, however, I found it really hard to stay focused on some of those details after spotting the rendering Metro tweeted yesterday (also found at the top of article).

It that made me think that six months might not be nearly long enough for the Metro, the County, and the developer to get things right with the community.

That image portrays a historically black community as a white mecca.

White people stroll, white people bike, white people regale each other with fascinating tales as they cross the street with fashionable purses, white people gaze at the tracks in deep thought and talk on the phone, and white people keep their distance from the lone black person wearing what appear to be cargo shorts across the way.

There seems to be some awareness that the overwhelming whiteness of this vision is problematic: the same rendering submitted to the Metro board for consideration includes some black cyclists (below, see also: PDF of Attachment C).

Which could be a step in the right direction if a) it didn't appear that the women had been lifted directly from a brochure on equity in active transportation (ahem, behold); b) there were more people of color who resembled people I actually see in the community; c) I didn't actually recognize the woman on the right as Ayesha McGowan, a badass cyclist on a quest to become the first female African-American professional cyclist; and d) the image didn't seem so devoid of any indications that these people are in a historically black neighborhood on a historic street adjacent to an important church that is deeply rooted in the community and at a corner that used to provide both really good community eats and services to folks trying to transcend the damage done to the community by white flight and disenfranchisement.

Which raises the question: where is the actual community that lives there now?

Where are the impeccably dressed churchgoers? Where are the black families? Where are the elders? Where are the black and Latino students, artists, and entrepreneurs? Where are the low-riders, area fixie riders, and folks biking out of necessity? Where are the black and Latino workers and job seekers? Where are the vendors? And where is that gentleman from the Nation of Islam that sells bean pies near Rodeo?

Are we planning for them?

The image suggests we might not be.

For one, Metro chose a for-profit developer over three teams that included affordable housing developers and promised more affordable units, including one offering 51 units at 30 percent AMI (and 300 fewer parking spaces). It also declared that the proposal by the Crenshaw Corridor Venture, LLP (helmed by the West Angeles Community Development Corporation) while very competitive, scored relatively low "in proposed development program/vision and financial offer" by promising nearly $40 million less in rent over the duration of the lease. Meaning that Metro eschewed nurturing a potentially more community-serving project in favor of one that was more lucrative. [See Attachment B: Procurement Summary]

Obviously, it is difficult to compare projects' respective viability or potential without the actual proposals in hand. But it is still possible to say that with all the changes coming to the corridor that have the potential to fuel gentrification, including the revamping of the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza (at the King Blvd. station) and the construction of District Square (next door), it is disappointing that there isn't more of an effort to secure more affordable housing for transit-dependent folks at the actual stations.

As of now, the Plaza project is reluctantly offering ten percent of its 961 units as affordable (only five percent will be reserved for those at or below 50 percent AMI) and the District Square project, which is expected to have 200 units, will also likely have just the minimum of affordable units, at best. There are a few affordable housing projects slated for that stretch of Crenshaw, but most are designated senior housing. Working-class families will likely have to look elsewhere.

For another, the lack of representation in images tends to signal either a lack of engagement with the community in the planning process or the lack of a deeper understanding on the part of the planners or consultants of who the community is and what its aspirations might be.

Too often, it means both.

In Boyle Heights, the rendering touting the transformation of Mariachi Plaza (above) not only erased the very Mariachis for whom the plaza was named, it replaced them with so many picnicking white people on a previously non-existent grassy knoll that there wasn't room for the plaza's current users: the Mariachis, the skaters, the dancers, the families, the community vendors, or the grassroots groups that do food distributions to community members in need.

What little trust Metro had had with the community was effectively shattered.

The project was so inappropriate and the uproar was so intense that Metro ended up having to start over from scratch - a process that has been underway for almost three years, at this point.

The graphic for the Rail-to-River project - the conversion of the Slauson corridor rail right-of-way from Crenshaw to the Blue Line (and eventually to the river) into a path for walking, cycling, skating, and relaxing - also hints at the struggle Metro has had getting planning with communities like South L.A. right (above).

When I first started covering the project in 2013, I was explicitly told by Metro and the consulting team that Metro was limiting its engagement with the community so as not to raise residents' hopes in case funding didn't come through.

What that meant in practice was that they studied the feasibility of the project they felt was needed - an "active transportation corridor" people could use to connect to transit on foot or by bike. There was very little consideration of what a project would look like that was more in line with what the corridor communities wanted or how they would be likely to use it.

There will indeed be those that use it to commute across South L.A., especially by bike and by skateboard, and to connect to transit.

But the dearth of opens spaces and safe public places where families and friends can gather, exercise, and relax means the most frequent users of the path are likely to be joggers and exercise station aficionados, families out for a walk with small kids, young kids learning to ride bikes, youth seeking safe and smooth places to skateboard with friends, area low-rider and other groups staking out neighborhood meet-up spots, and existing vendors (many of whom have been there a decade already) looking to grow their clientele while continuing to serve as eyes on the street.

To its credit, Metro has worked to be more transparent and responsive on the project over the last two years. But because it began designing in a vacuum, the effort to adapt that original sterile vision to the cultures, needs, and aspirations of the communities that live, work, move, and hope to recreate along it has remained somewhat hit or miss.

Even where Metro has made a genuine effort to partner with local groups representing lower-income communities of color, as it recently did with bike-share, those groups have continued to feel tokenized, misunderstood, and undervalued. [See video above; an in-depth look at the bike-share partnership with Metro coming later this week.]

Metro, they have argued, has been unwilling to hear and incorporate the full range of their concerns into planning. All of which has made them feel that their communities - the core of Metro's transit ridership - are less likely to be properly served. And all of which has caused them to raise questions about the extent to which Metro can be counted on to help guard against displacement and gentrification as it continues to build out its system.

This may seem like quite the tangent to go on based on a couple of images. But it's not.

These aren't the first images that have erased the physical, cultural, social, or economic presence of particular communities, nor will they be the last.

The images we use are aspirational - they tell us something about what we hope a space can be and who it will attract. The whiteness of the figures used signals newness, upward mobility and disposable income, safety, civic engagement and vibrancy, and the notion that the space is open to all (where a black- or brown-populated space might signal the project was "for" a specific group, type of activity, or culture). For private investors tracking public investment in disenfranchised communities, in particular, these sorts of images help prime the area for speculation and facilitate its rebranding as one that is "up and coming" and ready to be remade.

The shortage of folks of color and those with varying shapes, sizes, abilities, occupations, incomes, and gender identities who can be placed into renderings suggests we aren't ready to tackle those biases - either in the way we think about what constitutes a community or what vibrancy really means.

Perhaps more telling, it suggests we aren't interested in recognizing and celebrating the communities that are already in our urban cores and that we do not value all that they contribute to the life of our cities.

But being able to present renderings that are truer to the communities we build for also means more than dropping in the occasional Ayesha McGowan - awesome and fierce as she may be.

For public agencies like Metro, in particular, it means historically disenfranchised communities must be the starting point, not the thing to be sanitized or molded to fit a project after the fact.

In the case of joint development projects like this one, where Metro and the County own the land but will lease it to a developer, both entities have a responsibility to make sure that engagement is ongoing and meaningful. And that we end up in a much better place than we are starting from with a much better and more community-serving project.

The proposal for an interim ENA with this developer goes before the Executive Management Committee for approval this Thursday, November 16, at 11:30 a.m. Should it be approved, the interim engagement period prove fruitful, and the project be found to be acceptable to both Metro and the community, Metro will seek a standard 18-month ENA to allow the design and preparation for construction to move forward. Find the project-related documents here.