"That's where we got pressed!"

"That's where that kid got stabbed!"

Dayana de la Torre of Community Coalition is driving us through South Central on a Sunday afternoon. We are on a mission to photograph sites that high schoolers Juan Carlos (J.C.) Mercado and Miguel Sanchez have identified as being integral to their contribution to Re-Imagine Justice - Community Coalition's month-long Living Art Museum and panel series commemorating the 25th anniversary of the 1992 unrest/uprising.

J.C. and Miguel are hoping that before-and-after images of several sites they've identified will tell us something about stasis and change in the 25 years since the acquittal of four white officers in the videotaped beating of Rodney King sent people roiling into the streets back on April 29, 1992.

But in transit to those sites, the teens have managed to give me a very personalized tour through their own experiences.

And as they point out spots where they or someone they know has recently experienced some form of violence, their own narratives begin to complicate the before-and-after story they were looking to tell.

As we pass Fremont High School, J.C. gestures and asks if I remember that story they told me about that guy that shoved a gun in their faces while they were skateboarding around the school that one afternoon.

It wasn't this side of the school, he says of where they got hit up. It was the other entrance.

I nod.

When I had sat down with them and another student, John Linares, a couple of weeks prior at Community Coalition, where they are all active in the organization's youth leadership program, the story had tumbled out in between giggles, head shakes, and shudders at the memory of fearing that they or their friends could end up with a massive hole in their chest over a phone or a couple of bucks.

They had actually recognized the guy - he was from the neighborhood. And he had had a young apprentice with him - a middle-schooler they also knew by sight. But he had come up on them so fast and so purposefully and had such a big gun that they had frozen. It took a minute for their brains to register that this was actually happening.

After the guy rifled through their pockets and moved on, they realized they still had to make it back home safely.

Shifting their remaining possessions to harder-to-access pockets and looking over their shoulders every few minutes, they got the hell out of there.

Of course they never called the police, they said.

It was one of a number of violent altercations they told me about that afternoon: there was a kid that had gotten shot 12 times for painting a mural a couple of blocks from one of their homes, a college-bound kid who got killed by his girlfriend's gang-banger ex, that chubby kid that got killed up the street (they pumped a lot of bullets in him, Miguel said solemnly), shots fired in front of Fremont High School by a student that came back to school the following week, and the gunfire that erupted at the store across the street where Miguel's sister had gone and the panic he felt when he realized he was helpless to come to her aid if she got caught in the crossfire.

"I have lots of pictures," Miguel said of the documentation he's done of the scenes that have unfolded on his street.

It was a macabre hobby, to be sure, but one that spoke to what all the youth had said in one way or another: these sorts of incidents were normal for them. They have simply adapted to their surroundings.

They are not shocked at seeing women working the streets around their schools at all hours of the day. They don't hang out outside too much or wander around on their own. They know better than to take evening jogs through the neighborhood like a normal high schooler training for a sport might. They are careful about which streets and corners they move through. They've excised certain colors from their wardrobes. They stash their cash and phones in their socks and hidden pockets if they're heading out into the street. They might even carry a blade, if they feel they will have to defend themselves. Somewhere in their brains, they've got a hefty catalog of every shot they've heard fired and every body they've seen drop, but they tend not to say too much about it.

But saying they've normalized living within these constraints is not the same as saying they've found it easy.

It's not unusual for random people to get hit with bullets meant for other bodies, John said quietly. Every time he heads to the bus stop, he is aware he could easily get caught up in someone else's battle. As the first member of his family headed for higher education and someone who feels the weight of his family's expectations, "I think about that all the time."

People say South Central has changed in the last 25 years, J.C. said, but he has his doubts. There's a tendency to romanticize the "beautiful struggle" so many live in South Central, when in reality, the struggle can be painful, frustrating, fickle, and merciless.

It's part of what makes assessing where South Central finds itself 25 years on such a challenge.

Disinvestment, disenfranchisement, and denial of opportunity continue to define the landscape. Daryl Gates and his wretched battering ram may be gone, but young men of color are still being regularly hassled, demeaned, threatened, arrested without cause, and even killed by law enforcement. Jobs are still scarce, access to a quality education remains a challenge, and opportunities for growth, recreation, and fun are still few and far between. The instability and insecurity those structural conditions have produced continue to fuel gang violence and crime. And although overall violence and crime may be down and the crack epidemic may have waned, the inequities deliberately embedded in the system that allowed those things to flourish in the first place remain firmly rooted in it.

That said, it is imperative that South Central not be defined as the sum of its struggles.

To take that approach would be to overlook the community's most powerful sources of strength and hope: the very same youth who are questioning the status quo and the community-based leaders that, through their work with organizations like Community Coalition, have made it possible for the youth to do so.

So many leaders, advocates, organizers, artists, and residents in the area have dedicated their lives to strengthening the foundation of the community through some form of engagement.

They live, eat, sleep, and breathe justice, mentoring, and youth and community empowerment. They've started in-school and after-school programs, volunteered to stand on corners to give youth safe passage, founded youth-oriented bike clubs, reclaimed parks for recreation, taught art and nurtured innovation, let youth hang out at their homes and businesses and found creative ways to employ them, given talks to youth about how not to give in to their circumstances or make the mistakes they did, taught youth to conduct research and analyze their surroundings, created forums for community conversations, and organized around housing, transportation, healthy food access, fair wages, and a cleaner environment. In more than one case I know of, they might have even continued to deal drugs or gang bang out of necessity but volunteered to help out at community events because they desperately want neighborhood kids to have a better life than they did.

At Community Coalition, in particular, leaders have given youth a second home away from home, nurtured their dreams, engaged them on issues that affect them directly, connected their local struggles to larger national movements against injustice, and taught the youth how to organize their peers and neighbors around what they feel matters most to the community.

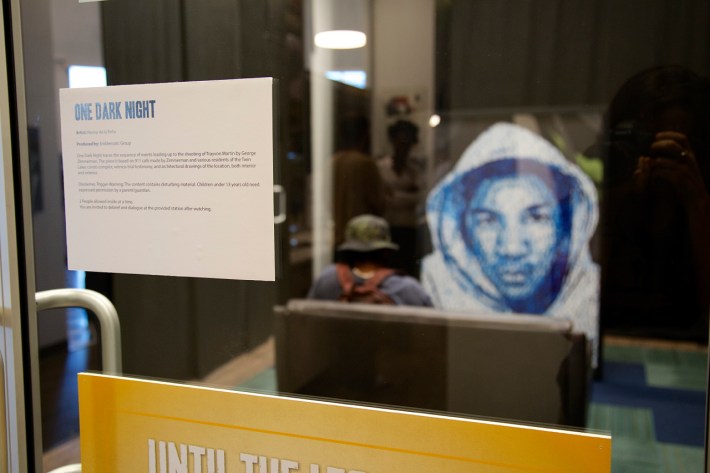

And in putting together the living museum for the 25th anniversary of the unrest, CoCo was able to remind the youth that the community was rich in untapped artistry and that the youths' own stories and experiences were integral to where South L.A. is headed.

The collective investment in its youth by the larger South Central community has paid off.

The youth I spoke with at CoCo and many others across South Central - even those that feel deeply oppressed by their circumstances - rarely talk about "getting out" of their community. Instead, they have a deep love for the community and a sense of pride in its refusal to give in to adversity. They prefer to toss around different ideas for how they might give back to the community, invest in it, and encourage others to help them take aim at the structural injustices that perpetuate the status quo.

It's a powerful thing to witness. But it really isn't that surprising.

Resilience is a hallmark of this place and its people.

Where developers have held neighborhoods hostage to blight for 25 years, intrepid vendors have seen opportunities to support their families.

Where folks were denied access to the public space, community coalesced in private spaces. Family, neighbors, and community groups stood and continue to stand as pillars of power, hope, liberty, growth, and regeneration.

When they saw the way they were misrepresented (or not represented at all) in the media and how their own images were used against them, area artists used their voices to redefine their communities and their relationship to this city and this nation in ways that spoke more honestly to their own experience.

When folks were left to fend for themselves in their neighborhoods, they took inspiration from voices that spoke uncomfortable truths and looked to each other for solutions.

When new images of familiar forms of brutality began appearing on our screens, they revisited lessons learned from local struggles and built new coalitions.

And they drew new connections to the long-standing problem of anti-Blackness, rallying Latino and Black Angelenos alike to call out the criminalization of Black bodies and of Black children, in particular.

These are the stories that are often not told about the community.

Yet, as we moved from site to site, snapping images of today's South L.A., these were the kinds of stories that interested Miguel and J.C. the most. There was no simple answer to be had with regard to where South Central has been in the past 25 years, or where it would be headed now. But they could see that the clues lay in the stories of its diverse population and the resilience with which those residents - themselves included - continued to weather the many storms visited upon them.

The Re-Imagine Justice exhibit will be up all this month at Community Coalition (8101 S. Vermont Avenue) and the public is welcome. Join the community for a panel discussion every Thursday at 6 p.m. and rally with residents at Florence and Normandie on April 29th. To learn more, visit cocosouthla.org/lauprising.