I did not attend the Women's March in Los Angeles on Saturday.

I watched the debates about what qualified as a "women's" issue unfold at the national level and I just couldn't get on board.

To be fair, though, I wasn't on board from the moment it was decided that there was going to be a march.

I'm not against marching by any means. And certainly I'm no fan of our bigoted pussygrabber-in-chief.

But I am profoundly aware that this the first time in a long time that many progressives of privilege felt personally affronted or even threatened by what the voting populace hath wrought this past November: Was it really possible that half this country could so easily shrug off overt racism and white supremacist shenanigans? Sexism and the celebration of sexual assault? Homophobia? Xenophobia and the branding of entire groups of people as degenerates? The mocking of the disabled? The penchant for wall-building, banning, and exclusion? The stated support for Japanese internment or of torture?

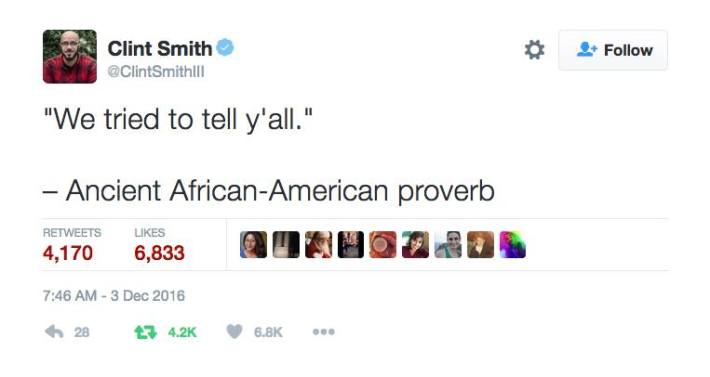

"Yes," came my and other voices from the margins. "This is not the first person that's been elected to office on a festering, hateful platform of ugly."

Which means that there is a great temptation to ask privileged progressives exactly where they have been all this time.

This, however, is not an approach that is particularly conducive to productive dialogue about the deep structural injustices embedded in the DNA of our nation or how unlikely that DNA is to be changed by marching in pussy hats. Rather, questions about the selectiveness of progressive outrage are more likely to put people on the defensive and invite some creative interpretations of history.

Perhaps my favorite such response came from a genuinely well-meaning white woman who laid the "It's Not Your Time" doctrine on me.

After railing about how "petty" women of color were for asking others to support their "specific and tangential" causes at what was meant to be a "women's march," she advised:

Before you laugh, shake your head, and agree that that is indeed a sad state of affairs, please know that if you are a person of privilege, especially one in the urban planning/transportation/mobility advocacy community, it is more than likely that, at some point in time, you have used the "It's Not Your Time" doctrine to silence voices of color, LGBTQIA people, immigrants, or others on the margins.

You may not have meant to do it.

And you probably meant extremely well when you did it.

But the effect was still the same.

I can say that with some certainty because, over the last five years that I've been writing about how and where planning, transportation, race, class, equity, and justice intersect in two disenfranchised lower-income communities of color, I've gotten several lifetimes' worth of "It's Not Your Time" pushback from this otherwise very well-meaning and progressive community.

When I raised questions about the impact luxury residential towers would have on Historic South Central - the most overcrowded neighborhood in the country and one of the poorest in the city - I was dismissed out of hand, told I was too stupid to understand basic supply and demand, and reminded we were in a housing crisis (implying poor folks should suck up displacement and take one for the team). Vulnerable residents who feared being displaced from the city (not just their neighborhood) if rents were to rise were labeled selfish, whiny, poverty pimps who let their own neighborhoods decay, told they were delusional to think they had some kind of claim on place, and equated with wealthy NIMBY homeowners who protect their home values at everyone else's expense.

When I've spoken or written about racial profiling and other barriers lower-income folks of color face in trying to access the public space, parks, sidewalks, or bike lanes, I have been asked what those issues have to do with transportation, accused of demanding perfection at the expense of "good," told I am distracting from important issues, told that equity is an excuse to do nothing and that it is a non-profit "racket," told that the blood of people who die in the streets will be on my hands, told I am the only one planners or advocates have ever heard raise those concerns, told I spend too much time hanging out with the wrong people, asked if I even ride a bike, and told that until I have concrete alternatives to offer, I should just keep my mouth shut and let people who actually care about livable cities get things done.

When I wrote about the decision of an undocumented friend and long-time active transportation advocate to buy a car as a window into what it means to have so little control over where you live, where you work, and how you get around, privileged progressives... well, they lost their damn minds. Instead of taking an interest in how transit was failing those that relied on it most or how those failures helped explain the drop in bus ridership, particularly among undocumented folks who could opt for drivers' licenses, dissenters expressed deep disappointment that I would do transit so dirty. Others completely breezed past the look at the intersection of housing, transportation, jobs, and immigration status and fumed that I hadn't talked about the real problems - cars and car-centrism.

Then our short-fingered vulgarian was elected.

And instead of self-reflection in the days that followed, progressives in urbanist circles doubled down. Many took to the cybersphere, declaring the great diversity of cities to be the antidote to an angry tide of sexism, racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and other ills. In their more insane white-urbanist-fever-dream iterations, these treatises argued the truest way forward lay in building more urban housing (especially for rural folks and racists) while wholesale ignoring history, institutionalized race- and other -isms, white flight, contentious busing experiments, self-segregation, and the use of redlining, zoning, infrastructure, housing subsidies, repressive policing, disinvestment, and denial of opportunity to fuel and enforce de facto segregation.

The divide between the communities I write about and the well-meaning people of privilege who seek to plan or advocate on their behalf never felt deeper.

There are definite parallels between progressives' resistance to meaningful engagement on equity, justice, race, and class in planning and the country's reactionary response to the rise of black, brown, and LGBTQIA voices. And they give me great pause.

So, instead of taking to the streets, I lodged my protest by spending several days on the Blue Line train, listening.

I was following up on the civil rights complaint the Labor/Community Strategy Center (LCSC) had filed against Metro. Using Metro's own data, the LCSC had found that while African Americans only comprised 19 percent of rail riders, they regularly received nearly 50 percent of the citations for fare evasion and other infractions. More startling still, they were nearly 60 percent of the thousands of arrests on transit each year. Worst of all, a significant proportion of these citations and arrests happened along the Blue Line - the line cutting through South L.A. neighborhoods where black unemployment and underemployment is in the high double digits and where young black men (especially those coming from one of the several public housing developments in the area) struggle the most to find and retain steady jobs.

That our local agencies would think that the best way to manage fare evasion would be to disproportionately penalize and jail folks from some of our city's most historically distressed communities seems hard to fathom.

Except that it's not.

The policing of the movement of black men is part of the DNA of this city.

Decades of disinvestment, disenfranchisement, repressive policing and denial of opportunity in the neighborhoods along the Blue Line left many of the area's young men with few options for gainful employment. Those that turned to the hustle to get by were likely to see multiple or lengthy incarcerations, often for non-violent offenses, thanks to overzealous policing and draconian drug laws rooted in protecting whites - especially the white women blacks were said to be prone to raping - from the "menace" of the "negro cocaine fiend." Just being black in the vicinity of illicit activity was sometimes reason enough to be arrested. Under former police chief Daryl Gates (1978-1992), for example, not only was brutality rampant, but indiscriminate "sweeps" upended entire communities by sending thousands of black men to jail.

The human cost of this form of social engineering on generations of communities of color is beyond comprehension.

At the 103rd Street station in Watts one night, for example, I sat with four men (ranging in age from their early 20s to their mid-50s) all of whom said they had either been incarcerated or had siblings who were incarcerated. Or both. One man's brother had been incarcerated as an adult at age 17. Another's brother had been put on a chain gang at Angola and was now down in Huntsville, finishing out a 30-year-sentence. One man had been in and out of jail while battling a decade-plus-long crack addiction. Another man had just gotten out after 20 years in prison. He was desperate to stay out of trouble, he said, but was hustling weed on the side because he left prison with nothing and he had to eat.

For men of color in these kinds of circumstances, the Blue Line is a life line. With no access to a car, they are vulnerable. Out on the street, they are likely to be hassled by law enforcement (which can result in incarceration for some parole infraction or worse) or confronted, harassed, or robbed when crossing through different gang territories.

Metro and the Sheriff's approach to policing the Blue Line capitalizes on their vulnerability. Too poor to buy money-saving monthly or weekly passes, and not always able to scrape together enough change to pay for a day pass or a one-way fare, they are the easiest of pickings.

But being penalized for their poverty and their blackness is nothing new to them.

So, when asked about Trump's election and what they think it might mean for them, they shrug. A couple laugh. When your life has been lived at the intersection of so many vectors of both overt and institutionalized oppression, does the election of a bottom-feeding buffoon really signal that things are likely to change for you?

More likely than not it just means that, at most, you will see a shiny new version of the same old same old. Worst-case scenario, it comes with a fascist-style twist.

On the train ride home, I pondered the then-upcoming women's march. I wondered what kind of catchy slogan I could hold up at a protest that would capture the essence of the deep and lasting damage done by structural violence, institutionalized racism, mass incarceration, and discriminatory planning policies and practices. Or if there was some fun phrase which would encapsulate the extent to which white privilege shields so many well-meaning progressives from seeing the role white- and privilege-centered narratives, frameworks, institutions, and planning processes play in perpetuating those ills.

Nothing came to mind.

So, no, I did not march.

I listened instead.

Then I sat down to write.

Because this is not 1776.

This is 2017 and it is long past due for these truths to be self-evident.

It is indeed our time.