"In the interest of time," Greg Kildare, Executive Director of Metro's Enterprise Risk, Safety, and Asset Management team, began his address to the Board on July 23, "I will just say that staff believes that the [Metro Blue Line] pedestrian gating project is an extremely important safety improvement to our oldest rail line and consistent with [Metro CEO] Mr. Washington's vision of reinvestment in our aging infrastructure, the state of good repair, and a safety-first orientation. That concludes my presentation."

Agreeing that the upgrades were "long overdue," the Board approved the installation of $30,175,000 worth of Pedestrian Active Grade Crossing Improvements at the 27 intersections the Blue Line shares a right-of-way (ROW) with Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) without hesitation or discussion.

The improvements are indeed long overdue.

Between 2002 and 2012, 13 of the 18 non-suicide* fatalities along the Blue Line happened between Vernon Ave. and Imperial Hwy. in South Los Angeles. [*Suicide is a significant issue along the Blue Line -- at least 30 of the nearly 80 pedestrian fatalities along the line over the last two decades were confirmed suicides.]

The wide openness of the at-grade crossings through that stretch, inadequate pedestrian infrastructure, and lack of barriers at a number of the intersections -- particularly on the UPRR side -- create dangerous conditions for pedestrians. None of which is helped by the fact that the tracks run adjacent to several major parks and through the middle of a housing development, meaning that families and kids might make the long trek across the tracks several times a day.

Because the freight trains that use the UPRR tracks run infrequently and move so slowly -- often inching forward, backing up, stopping, and inching forward again -- a train can appear to be more of a nuisance than a hazard.

Multiple trains on the tracks can throw off a pedestrian's calculations of which side a train is coming from, how fast it is moving, or how quickly the pedestrian feels they can get across the tracks. Or, as in the case of middle-schooler Gilberto Reynaga, killed in 1999 when he clambered over a freight train stopped at the intersection only to be hit by a passing Blue Line train at 55th and Long Beach Ave., there is a potential for people to be confused by the train the signals apply to and believe they are safe when they are not.

Even when people obey the signals, their journey from narrow pedestrian island to narrow pedestrian island can be lengthened by having to zig-zag their way across the tracks (above and below).

The trek can be made more stressful by the fact that the pedestrian countdown signal can be obscured by the rail gates as you zig-zag your way across (below) or the utter lack of pedestrian signals, in the cases where the intersection is governed only by stop signs (above) and pedestrians and drivers alike must navigate what is essentially a super-wide 6-way stop (given the separate left-turn lanes and stop sign signage on Long Beach Ave.).

In some areas, the poor condition of the pavement around the UPRR tracks can also present a hazard in that it makes it tough for people pushing kids in strollers, wheelchairs, vendor carts, groceries, or anything heavy on wheels, really, to get over them.

The safety of pedestrians and cyclists around what has sometimes been called "the deadliest rail line in the country," in other words, has always felt like an afterthought. Something Metro is not unaware of.

Two years ago, when I first sat down with Vijay Khawani, Executive Officer for Corporate Safety, he had pulled out a thick stack of marked-up drafts of Blue Line crossings to show me how Metro was working to determine which safety measures could go where.

Coming up with fixes for each intersection had already taken some time, he explained, as the narrowness of streets or pedestrian walkways adjacent to the tracks in some areas didn't allow sufficient space for swing gates or other protections.

And the more direct approach, Khawani had said at the time -- shutting down streets and completely reconfiguring the intersections to meet the standards seen on newer rail lines -- simply wasn't feasible.

Progress had also been thwarted by UPRR's fears that allowing Metro to install anything more than the most basic of safety protections alongside UPRR's ROW would trigger an avalanche of demands for UPRR to do the same along the thousands of miles of tracks they manage across the country.

It took years of wrangling to get UPRR to allow for the improvements to be made at all, I was told. And those concessions were only granted begrudgingly.

The struggle to get UPRR to take pedestrian safety seriously appears evident in Metro's Blue Line Safety Task Force report from November of 2012. Convened per an August 2012 motion by former Boardmember Zev Yaroslavsky to address the rise in collisions and fatalities along the Blue Line that year, the Task Force was asked to assess existing safety concerns and to "propose preventative and corrective actions to ensure [the] increase in incidents [did] not become a long-term trend."

Where input from Metro, LADOT, the City of Long Beach, and the City of L.A. in the report seemed to indicate a commitment to the installation of upgrades at the intersections hosting three and four sets of tracks, UPRR's comments suggested otherwise.

Some of the UPRR comments about potential upgrades contained the complaints that people would probably tamper with pedestrian gates (rendering them inoperable) or ignore them altogether (rendering them a waste). Other comments, apparently made in all seriousness, endorsed the notion that Metro look into "cowcatchers" for the front of its trains so as to minimize pedestrian deaths (at right). And UPRR reiterated several times that it expected to be reimbursed for all costs related to the design, construction, and maintenance of any infrastructure on its side of the tracks.

For its part, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) appears not to have had much patience with UPRR's protestations. It signaled its disapproval of the idea that safety gates might appear on only one side of the tracks at an intersection by saying,

We do...have some concerns with treating the UPRR side of the corridor differently than the Metro side of the alignment. In the effort to send a clear and understandable message to users, consistency should be a goal. We urge UPRR to look beyond its normal preferred configuration and resistance to active pedestrian gates along the line.

The Task Force concurred and concluded that swing gates could be installed at seven sites along the UPRR ROW and in-roadway warning lights would have to suffice where space did not permit (e.g. where opening a gate might force a wheelchair-bound person to roll back into the intersection). The added infrastructure would require an increase in the budget from $6,780,000 to $7,700,000, the report acknowledged, but the added safety measures were important. [See full Task Force report here]

When I spoke with Khawani in early 2013, he was preparing to submit the project by July of 2013 -- now including the limited number of gates planned for the UPRR side -- to bid so that work could begin immediately in the 2013 - 2014 fiscal year.

What happened next, I am not exactly sure. But it appears that, in September of 2014, the CPUC intervened and required not only that UPRR agree to allow the upgrades Metro would be implementing on its side of the ROW to also be implemented on UPRR's side, but that Metro go the full distance in overhauling all 27 intersections to install the full range of safety measures (not just where space permitted).

It would significantly raise the costs of project -- bumping the budget up from just under $8 million to approximately $30,175,000. And it required Metro return to the drawing board to redesign each of the intersections, delaying the ability of the project to move forward til now. But Metro purports to be rather pleased about this.

"This is a good thing!" Metro Systems Safety Manager Abdul Zohbi told me enthusiastically over the phone recently.

And so it appears to be. According to Metro, the ruling means that swing and pedestrian gates will now be installed at all four corners of all 27 of the problematic at-grade crossings -- a total of 108 quadrants. And to make that possible, given the inadequacy of the existing pedestrian walkways, major civil improvements will be undertaken to make room for such barriers, ensure ADA compliance, and widen pedestrian crossings.

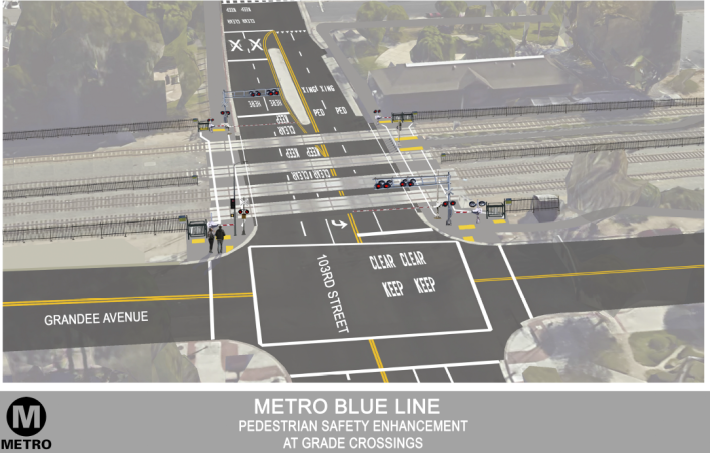

At 48th St., featured in several photos above, the new configuration will look like this:

The crosswalk will be widened and the spaces between the tracks filled in/covered so as to cut down on the zig-zagging. Pedestrian barriers (the arm that lowers) and swing gates will also be installed to prevent folks from venturing onto the UPRR tracks while they wait for a Metro train to pass (as I did easily, below). And it appears curbs on the outer edges of the intersections will also receive some upgrades.

People can still get around the barriers, if they are really determined, but as I first saw when I looked at the issue in 2013, pedestrian barriers can and do act as deterrents. A fully open crossing signals "Eh, nobody felt the need to try to stop you, so you'll probably be safe." (below)

A gate at least forces you to ask yourself, "Are you really sure you want to risk it?"

And there is a more tangible benefit to the gates as well -- Metro estimates that implementation of gates reduce both fatal and non-fatal incidents by half.

Quadrant gates blocking all four sets of travel lanes, as I understood it from the Task Force report, are not a priority now as collisions between trains and cars have been reduced over the years. But they were not ruled out for the future.

The funds for the project are to be drawn from Prop C over the next three fiscal years.

Metro's Zohbi told me the work should be done in about two years' time, once they get a notice to proceed and a contractor.

He concluded that the project would finally bring safety measures along the Blue Line up to par with those of the existing and future lines and, still enthusiastic, reiterated again, "This a good thing!"