Donald Shoup, parking's one and only rock star, is retiring from UCLA this year. Tomorrow, the college is sending him off with a fundraiser retirement dinner atop parking structure number 32. You can attend, and hobnob with Shoup himself, by donating to the Shoup Fellowship fund for future UCLA planning students.

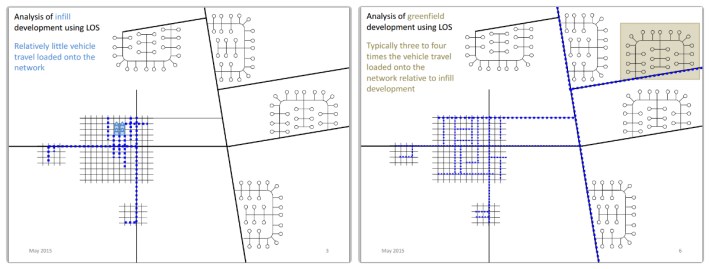

Below is part two of my big exit interview with Don Shoup. Part one is here. The interview took place at the UCLA Faculty Center on Friday, May 15, the day after UCLA's Complete Streets Forum, where Professor Shoup had been impressed with a presentation on the soon-to-be phased out car congestion metric, Level of Service.

Joe Linton: Many progressives want people to do the right thing for the right reason. If you look at New York City and how healthy people are, it's because they walk. They’re not healthier because they’re choosing some healthy option. They’re healthy because the neighborhood around them was built for walking. I think you've managed to avoid that pitfall.

Don Shoup: When it comes to public policy, doing the right thing is more important than doing it for the right reason. The best way to get people to do what’s right collectively is to make it the best thing for them to do individually. You have to give individuals a personal incentive to do what’s right for society.

When it comes to parking, you have to figure out how to stop giving everyone incentives to do what’s wrong for society. Removing subsidies for parking is one of the best ways to convince people to walk, bike, or ride the bus rather than drive solo.

For example, employer-paid parking is an invitation to drive to work alone. Parking cash out is a policy that makes it individually rational to consider all the alternatives to driving to work alone. I studied employers who began to offer commuters the option to choose the cash value of free parking rather than the parking itself. At these firms, 17 percent of the solo drivers shifted to carpooling, biking, walking, or riding the bus to work.

For many people, the only reason to do anything is that it’s best for them individually. And I think that’s why planners have to be more realistic about devising policies so the stakeholders will say, “I see what you mean - that’ll help me.” I think expecting people to do the right thing for the right reason leads to a lot of failure in public policy.

Most people who ride a bike do so because they enjoy it and want the exercise, not because it’s a sacrifice for humanity. But many people don’t mind driving or even like to drive, and parking subsidies increase the incentive to drive.

In my retirement, I want to live the way hobbits did; they spent all their time visiting all their friends who lived within a half a day’s walk. And if you are lucky, you can live almost that way in L.A. I live near campus and usually don’t leave Westwood. When I do go to other places like West Hollywood, Culver City, or Pasadena, I see there’s a whole other ecosystem going on in each neighborhood. There are a lot of little villages and you can have a wonderful life without traveling far from them. I've even seen real estate ads for houses saying "Park on Friday, walk all weekend."

Because of traffic congestion I think more people are leading their lives in their own villages. But I do think we can greatly reduce traffic congestion. I’m a big fan of congestion pricing - which I think is the only thing that will reduce congestion.

Linton: Where do you see congestion pricing taking hold in Los Angeles?

Shoup: It already has taken hold - the High Occupancy/Toll (HOT) lanes on the Harbor Freeway. Solo drivers can use the ExpressLanes if they pay. The tolls adjust up and down to prevent the lanes from getting congested.

Linton: What’s interesting to me is that it was working really well as we were emerging from the down economy - the speeds were actually averaging above the speed limit - which they were proud of - those scofflaw motorists. This year and late last year, as the economy has picked up, they’re increasingly closing those lanes. They’re too packed.

Shoup: Yes. It's because there is a cap on the congestion toll - $1.40 per mile. They now run up against that cap often. The price cap was politically necessary to begin with but there’s no reason to have a cap now, especially because the toll revenue provides many amenities on and alongside the freeway. Better lighting, better bus stops, and more frequent bus service.

Linton: Bike-share, too

Shoup: That’s right. So what’s the objection to raising the tolls now? The ExpressLane tolls provide about $2.3 million a month to run the extra bus service, bike-sharing, better bus stops, and things like that. If that’s what the tolls are providing, what’s the problem with raising the price for solo drivers when the freeway gets congested?

Linton: Where else do you think L.A. can expand congestion pricing? Additional freeway lanes? Other applications?

Shoup: They didn't need to add lanes to the El Monte Busway and the Harbor Freeway for congestion pricing. I think we should convert more HOV lanes to HOT lanes. On the 405, we just spent a billion dollars to put in one new HOV lane. It took five years of construction with nightmarish traffic - and just think of the carbon emissions that created. It would be more sensible to convert one free lane to a HOT lane.

After the Level of Service talk [at the prior day’s Complete Streets forum] a consultant from Orange County asked “if they don’t use Level of Service metrics, how will they know where to build new freeways, new capacity?” I said if you have a congested freeway, you could try converting free lanes into HOT lanes rather than build more free lanes. I think Orange County made a bad choice in expanding freeways and keeping them free.

If we manage freeways better - the lanes that we have - we wouldn't need any more. And they would provide revenue.

We ought to have signs on the bike stands, in the buses, and at bus stops saying “paid for by the ExpressLanes revenue.” People will see the toll revenue at work. The revenue goes to specific places for specific things. If we didn't have the congestion tolls, we wouldn't have these bicycles, this bus, this new street furniture, or something like that.

Variable parking prices are like congestion tolls, except instead of aiming for the right speed on the road you aim for the right occupancy rate for on-street parking –one or two open spaces on every block. It’s a lot easier to charge for parking than it is to charge congestion tolls. But most cities have the same price for curb parking all day long, or no price at all.

Linton: Have cities done a good job of adopting your recommendation to use parking meter revenue for improvements on metered blocks?

Shoup: Pasadena is a great example of using parking meter revenue to improve an area. You are probably too young to remember what Colorado Boulevard in Old Pasadena was like before the parking meters. It used to be a skid row.

There were wonderful buildings in terrible condition. Much of it had been urban renewed. The city tore out three blocks of Old Pasadena on Colorado Boulevard for an enclosed mall. Look at it from the air. What we think of as Old Pasadena is only what’s left of Old Pasadena - before freeways and redevelopment removed most of it.

Most of the buildings were empty above the ground floor. The rest of them were pawn shops, porn theaters, and tattoo parlors – there’s nothing wrong with that but it shouldn't be your only land use. The city wanted to put in parking meters. The merchants said “no way - it’ll chase away the few customers we have - down to this enclosed mall you subsidized.” They argued for a couple of years. Finally the city said “if we put in the parking meters, we’ll spend all of the revenue for added public services on the metered streets. We’ll rebuild all the sidewalks and clean up the alleys.” The merchants said “why didn't you tell us that before? Let’s run the meters until midnight. Let’s run ‘em on Sunday.” They were so excited when they knew they would get the revenue instead of going into the city general fund.

Linton: Revenue return is just one of the three main parking reforms that you recommend for cities. Explain those.

Shoup: I recommend three basic policies:

- First: charge the right price for curb parking – the lowest price the city can charge to leave one or two open spaces on every block, so everyone can easily find a convenient place to park.

- Second: spend the meter revenue so everyone - the landowners, the merchants, the residents, the stakeholders – can see it benefits them.

- Third: remove the off-street parking requirements.

If you do all three, they’ll be much more effective than any one alone. These three policies work together like the combination for your lock at the gym. Every turn of the dial doesn't seem to do much, but when you get all three of them right, the lock opens.

Some cities have adopted one or two of the three policies. For example, Los Angeles and San Francisco have variable meter prices in downtown, but they don’t return the revenue to pay for public services on the metered streets. Pasadena returns the meter revenue for public services, but it doesn't vary the meter prices according to demand. I think that all three policies together will show that the combination will do a lot more than each one alone.

Ventura has a unique program of variable meter prices and revenue return. The city engineer did a very clever thing in arranging the way the meters communicate with City Hall. To validate credit cards and to remotely change the meter prices, Ventura uses wi-fi rather than cell phones to handle the communication. Each meter has a low power transmitter, and every block has a router mounted on a light pole, connected to the power supply, to relay the signals to City Hall.

Ventura’s city engineer, Tom Mericle, realized that the routers had a lot of excess capacity because they don’t validate many credit cards during an hour, so the city opened the wi-fi for public use. Everybody on the metered street gets free wi-fi, courtesy of the parking service! This free wi-fi is a by-product of having the parking meters. If you’re at a coffee shop or a restaurant, your free wi-fi is ready, courtesy of the parking service. Restaurants and coffee shops don’t have to provide wi-fi to their customers, because the meters do.

I hope that parking meters around the world will become identified as a source of wi-fi. If you have meters in your neighborhood, you get free wi-fi. If you don’t have meters - that’s your choice - you don’t get free wi-fi.

Linton: Any other good examples? Parking in other countries?

Mexico City has begun to have neighborhood votes for parking meters. Mexico City returns 40 percent of the meter revenue to the metered neighborhoods to spend on public services, and there have been political campaigns using social media for and against parking meters in each neighborhood.

Many people want the parking meters to get the revenue and to get rid of the chaotic parking conditions. In some neighborhoods, mafia-like organizations had commandeered the on-street parking and charged for it but the money doesn't go to the government - it goes to the parking thugs. In elections for parking meters to replace the parking mafia, people campaigning for meters have put posters on the walls that say “Parquimetro Sí.” If it weren't for the revenue return, of course, no one would campaign for parking meters. So that’s why is so important for a city to promise that the meter revenue will go for parks and sidewalks in the neighborhood.

Not that every city will want to have votes about parking meters, but in countries where there is a democratic tradition, and where the transportation professionals want to see parking reforms, revenue return is a key to gaining political support.

Some neighborhoods have voted against the meters - that’s their choice. When it comes to parking, I’m pro-choice!

Linton: How do you get your ideas out into the world?

Shoup: I've been very fortunate that journalists like you have been interested in my work. Journalists know how to write in a way that will keep people reading.

Academic writing is generally for other academics, and you must maintain an appropriate analytic or theoretical stance, without being an advocate. In academic articles you’re supposed to be doing research, not preaching. But I also like to preach about parking reforms, so I have a second life, separate from being an academic, speaking in cities around the country and the world.

Professors of urban planning shouldn't preach a political agenda and shouldn't try to indoctrinate students. We should give them intellectual tools and encourage them to make their own use of whatever we offer in terms of statistics, math, economics, history, design, and theory. Academics like to be seen as impartial, although of course we have our own preferences.

But we have to act impartially in a classroom. I think that the way professors have the greatest effect is really through the careers of our students, not through our publications. The real accomplishment I think is helping our students to have successful careers and, at least in planning, to do a lot of good for the world. Teaching, rather than research, is probably where we have the greatest effect.

When it comes to research I think my ideas have been disseminated through journalists who don’t have to be impartial - well I suppose some journalists have to appear impartial too but Streetsblog doesn't have to. Streetsblog isn't like the New York Times where you always have to get a dissenting view for every story. I've been very lucky in that journalists, both here and abroad, have been very sympathetic to what I have to say.

Linton: When I read even the L.A. Times or I watch T.V. news, I don't find it impartial regarding cars. It’s pro-car as much as Level of Service. It’s about as impartial as LOS is. We've got a lot of built-in biases that say “cars are the way to go.”

Shoup: This pro-car bias explains why proposals to charge for parking are often such a non-starter. That’s why, instead of emphasizing the benefits of charging for parking, I emphasize the benefits of using the revenue to provide public services on the metered streets so that people can see that they, personally, will benefit.

Everybody wants to park free, including me. You can’t neglect that. You have to recommend policies that will allow people to see their meters as cash registers for their neighborhood. Unless you do that, I think you’re just talking to the wind - if you just say "we ought to charge for parking."

Politicians always say about parking meters, "we’re not doing it for the money, we’re doing it to regulate traffic" but of course that’s not true. If it weren't for the money, cities would be much less interested in parking meters. If the money went to pay for the UN, you wouldn't see that many parking meters. You’d just have one-hour time limits or other non-price regulations.

Linton: I think it’s also invisible. A Metro spokesperson said “ Our objective is not to make money on parking.” Metro has, what, 20,000 parking spaces, nearly all free. The neutral tone “we’re just being nice giving free parking” disguises that Metro actually spent hundreds of millions of dollars on parking. This is their big loss leader. One of the dirty little secrets of free parking is that it’s the loss leader. It’s where we give away a bunch of money to specific people. It’s not neutral.

Shoup: Free parking gives away money to drivers, and nothing to anybody else, including people who are too poor to own a car.

I am currently in a debate about a new bill in the California legislature, A.B. 744, which would put a cap on parking requirements for affordable housing. In one of those impartial academic articles, I used industry data to show that the average cost of a parking space in an above ground parking structure in the U.S. is about $24,000 and the average cost in an underground parking structure is about $34,000.

When planners set parking requirements for affordable housing they don’t even mention the cost of parking spaces, as though it were irrelevant. But how does that cost of parking compare with the wealth of the people who live in this affordable housing?

The U.S. Census has data on median net wealth - all your assets minus all your liabilities. The median net wealth for Black households is only $6,600. Half of all Black households in the U.S. have net wealth less than $6,600. The median net wealth for Hispanic households is $7,700. Therefore, the average cost of a single space in a parking structure is at least three times the net wealth of more than half of all Black and Hispanic households in the country.

And 33 percent of all Black households have a negative net wealth - a lot of them are way in debt for credit cards, college loans, or car loans.

When a city council sets minimum parking requirements, they say, "I know how much parking this housing needs - we can’t let it be built with less than two spaces." Beyond that, there have to be four spaces per thousand square-feet in a grocery store. And ten spaces per thousand square-feet in a restaurant. The city council knows all this even though they have no idea of how much the parking spaces cost or the income or the wealth of everyone who will have to pay for the free parking in higher prices for everything they buy.

We have scarce, expensive housing for people but we want ample free parking for cars.

Linton: I think one of the myths in Los Angeles is the driving poor. If we charge for ExpressLanes or charge for parking, we hurt those poor people who scrape together enough money to have a car. I think it’s bogus; really poor people don’t have cars in my neighborhood, in the urban core.

Shoup: People who oppose tolls or charging for parking often push poor people out in front of them like human shields, saying "don’t charge for parking - it’ll harm the poor" when what they really mean is "don’t charge for parking - I don’t want to pay."

It’s always politically acceptable to oppose a policy by saying say it will hurt the poor. If you’re that concerned about equity, you could give a discount for poor people. You can give them an allowance at meters. If poverty is your real concern, a city can give discounts for poor people at parking meters. We do it with water, with electricity, with telephones.

Linton: ExpressLanes even.

Shoup: Is that right?

Linton: Absolutely

Shoup: Cities can give discounts at parking meters for low-income users, if equity is your real concern. But I would say one of the cruelest things we've done with our parking policies - or Levels of Service - is to create a world where almost everybody needs a car to make a living and to have a good life. We've created an environment in which most people feel they need to have a car. And, in many cases, to have good access to a job or health care or whatever, a car is a great asset. Parking requirements and LOS requirements have helped to create this car-friendly environment. You don’t need a car so much if you live in a dense grid pattern. You probably do need a car in a low-density subdivision. Our public policies are forcing most development to be car-dependent.

How could you blame somebody who is living hand to mouth for borrowing at a sub-prime interest rate to buy a car? There’s a whole new industry of sub-prime car loans. It’s painful to think of people who feel that they need a car because we have planned the world in which they need a car. Many people seem to think that parking spaces in an apartment building are as necessary as lifeboats on a cruise ship, even for people who are too poor to own a car.

We've created an environment where much of our wealth is tied up in free parking. But a city where everyone pays for everyone else’s free parking is a fool’s paradise.