"I can honestly say my faith in humanity has been restored today," Joey said Wednesday as we popped his back tire back on his bike and I packed up my patch kit. "If I ever see you in the street again, I promise I'll pay you back somehow."

His declaration was quite sincere. He was worried that his boss was going to be upset at how late he was. He was still 20+ minutes away from the tire shop on Western where he worked, on foot, and he didn't have fare for the bus or train on him. He was kind of bummed because the bike was new, too. A car making a hard right without warning had tossed both him and his previous bike into the air. He managed to walk away from the incident OK. The bike, not so much. He couldn't afford to see this one damaged.

"I don't even know what I hit," he had said when I first spotted him walking his bike along Exposition Blvd. "I had been watching for glass..."

Glass wasn't the issue this time. When we flipped the bike over and took a look at the wheel, we found a twisted industrial staple that I ended up having to yank out with my teeth after the embedded section broke off inside the tire.

"Here," I tossed him my patch kit. "Grab one of the smaller patches and the glue while I find the hole in the tube."

"Cool," he nodded. "I was just going to fix it at work [with a patch for car tires]."

The imperfect fix he had planned did not surprise me. Like the majority of the folks whose tires I've stopped to patch in South L.A. (something that happens, on average, every other week), he was riding out of necessity, and something as basic as a popped tire could impinge on both his budget for the month (it's a $6 to $8 fix at local shops) and his ability to get from A to B in a timely way.

Joey was fortunate in that, aside from the cheap and slightly-loose-on-the-rim tires, his bike was rather solid. Too many of the lower-income commuters I've spoken with are not riding on such reliable steeds.

Such as the youth whose crank kept coming loose at inopportune times and causing him to fall over in the street, occasionally in front of cars. Or the youth on the road bike with broken brakes who was wearing holes into the bottom of his shoes after he resigned himself to braking Fred Flintstone-style. Or the numerous men and youth whose rims have been damaged by collisions with cars but who couldn't afford new wheels. Or the school kid whose rim snakebit his tube beyond repair and who cried on the phone when his mom said that was the end of his days of biking to school. Or the young man whose valve detached from the tube when we tried to fix his flat and who got a loaner tube from a friend on the condition he try to scrape together the $3 to buy one from a nearby sidewalk bike vendor as soon as possible. Or Watts resident Marcus, who had been able to convince a dollar store owner to sell him a patch kit for the $.88 he had in his pocket but who then had no way to pump up the tire. He called me at 11 p.m. a week later, from near Ted Watkins park, stranded with another flat. Was I in the area? He was afraid he wouldn't be able to traverse the last 15 blocks home safely that night.

The struggle very low-income commuters face in maintaining bikes that were never in great shape to begin with is so bad that the owner of the Watts Cyclery even found himself having to create layaway and monthly payment plans for people who desperately needed a bike or a fix, but couldn't pay for it upfront.

Despite the many odds they face, low and very low-income commuters consistently comprise a significant proportion of the total commuter cycling pool. And many more would likely bike, provided they could either easily/cheaply access solid bikes or get their existing bikes up and running again.

Which is why it is so unfortunate that Metro's approach to bike week isn't more reflective of their experience.

I don't deny that it is paramount to target those who are contemplating switching out four wheels for two and taking their first spin to work. But it is also incredibly important not to lose sight of who is already out there and what the range of their needs might be.

In aiming for the cycling convert of choice, the messaging tends to stall in the realm of how to make cycling as fun, easy, safe, and community-building as possible. Free films! Free snacks! Style guides! A free day on transit (not much of a draw to lower-income folks who are more likely to have weekly passes)! Free stickers! Happy hour parties! Like-minded people!

Which is not to say these are terrible things.

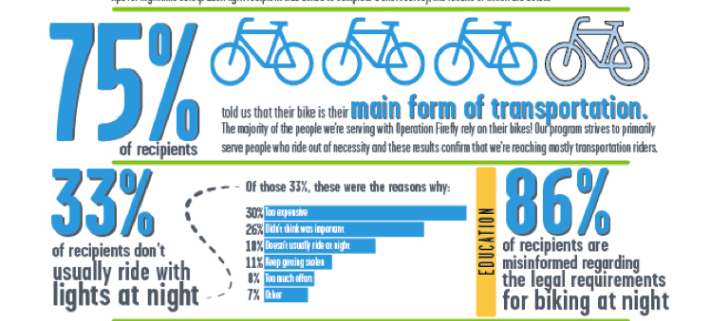

But they are not as inclusive as they could be -- something discussions at events held earlier this week alluded to. At the kick-off press conference, Metro Boardmember Jackie Dupont-Walker referenced the importance of supporting "everyday bicycling, repeatedly saying that it is not about “bike week” but “bike life,” while the LACBC released a fact sheet compiling survey data from their bike light giveaways to lower-income riders. At forums on infrastructure and law enforcement, LACBC Executive Director Tamika Butler, advocate Erick Huerta, and others reiterated the importance of accounting for the wider range of socio-economic challenges faced by people of color and the way those factors can impact mobility.

Even having translated materials more readily available and being more deeply engaged with local organizations that work with lower-income commuters of color -- perhaps even helping support and staff bike week events/pit stops in those communities, noted Huerta, would be a step in the right direction.

Beyond being the right thing to do, a more inclusive approach might help keep those already on bikes from seeking to one day exchange two wheels for four. It is unfortunately not so unusual to hear many of those who are riding out of necessity -- youth, in particular -- hope for the day when they can have their own car. Bikes and transit, for many, can carry the stigmas of dependence and lower status. Such riders are also more easily targeted by police when on bikes. In areas where gang activity impacts safety in the public space, a car can represent a more secure form of mobility for both youth and families. A car is also helpful for those who need to get back and forth to work in the middle of the night, when transit isn't running and streets are eerily quiet, but not necessarily safe. And, as illustrated above, what may be a more economic alternative for a person of means can actually be a less reliable and more costly form of transportation when a person doesn't have the resources to purchase a decent bike to start with or the ability to reach a repair shop because their primary mode of transportation is broken.

Metro made some steps in the right direction this bike week, including the implementation of three-bike bus racks and the announcement of a $224,000 initiative for a series of bicycle safety education classes.

But carrying a commitment to "bike life" forward will entail much more. A few of the many steps that could be taken include: ensuring first mile/last mile connections help riders access key bus routes as well as rail hubs; working with the Sheriffs and LAPD to limit the harassment of lower-income people of color at Metro stations and to ensure bus stops are safe; going beyond bike safety classes to support the building of bike co-ops, repair stations, or even weekly or bi-weekly repair pop-ups to be sited at important bus and rail hubs in communities of need (possibly even making the bikes gathering dust in their lost-and-found available for such endeavors?); engaging lower-income communities about their aspirations and following through on the commitment to affordable housing so that lower-income commuters can afford to remain in transit-rich communities; and elevating the transit experience (particularly the bus experience) so that those who must bike and use transit out of necessity are finally shown they are as valued as the more affluent rider of choice.

Because for Los Angeles to successfully forge a path towards the safer, stronger, more prosperous, and more resilient city our transportation leadership spoke of at the launch of bike week, its most vulnerable residents cannot be left out of the conversation.

That road must be inclusive.