With today's deadline looming for comments on new rules governing the way the state analyzes transportation planning impacts, many transportation planners and engineers remain confused about what the new rules might mean while others join advocates in hoping that new rules will create better projects.

SB 743, signed into law last year, removes traffic Level of Service (LOS), a measure of traffic congestion, from the list of environmental impact metrics that have to be used under the California Environmental Quality Act when planning development and transportation projects. The Governor's Office of Planning and Research (OPR) has to decide on a substitute for LOS that more broadly measures a project's transportation impacts. Although SB 743 says LOS must be replaced in dense urban areas with robust transit access, OPR can also decide to apply that new metric everywhere in the state.

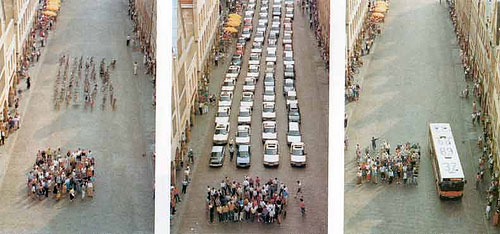

Focusing on LOS has severely hindered the expansion of bike lanes in California, including a lawsuit that delayed San Francisco's bike plan for years because it might delay car traffic. Critics of LOS have long argued that using a metric that solely measures the movement of cars, rather than the movement of people, makes for an inefficient transportation system and requires costly measures to "mitigate" LOS impacts.

"CEQA rules were so backward that you had to analyze the environmental impact of replacing a 'car' lane with a bike lane but you could remove a bike lane to add a car lane with no analysis required whatsoever," said Dave Snyder, executive director of the California Bicycle Coalition.

“It's not just for bikes, either, but for any street improvement that involves reducing car capacity," he added, "which is to say transit lanes, sidewalk bulbouts, or all manner of changes that make a place more livable, safer, and more prosperous, if a bit more congested with automobiles.”

Another example would be converting a mixed traffic lane to a bus-only lane. In the past couple of years, there has been a debate in Los Angeles over expanding the Wilshire Bus Only Lane. Studies showed a net increase in vehicle congestion in the remaining mixed traffic lanes with a major reduction in travel time for buses. More people ride the bus on Wilshire Boulevard than drive, but that didn't stop opponents of the bus line from charging that the project was bad for commuters.

Rebecca Long, senior legislative analyst at the Bay Area's Metropolitan Transportation Commission, says that by focusing on LOS, transportation analysis has often undermined environmental goals. “Congestion itself is inevitable,” she points out. “And it has some positive effects, like getting people to take transit” rather than driving, thus reducing per capita emissions.

Which is not to say removing the LOS standard for state environmental review is a universally popular idea.

Streetsblog reached out to planners throughout the state, in cities and counties, and found uncertainty and some confusion about what the new law and the proposed rules might mean for them.

Speaking off the record, because their departments have not yet determined their official responses to OPR's request for comments, they expressed concerns about how jurisdictions will determine traffic impact fees -- an important source of funds -- if not through LOS, and about how transit planning can take into account impacts on vehicle traffic.

However, none of these uses of LOS are affected by SB 743 or the state's proposed CEQA changes. Martin Engelmann, deputy executive director of Planning at the Contra Costa County Transportation Authority, pointed out that LOS is still required under the state's congestion management laws and that many general plans and zoning regulations include LOS standards. “It's not like LOS is going to disappear — it will just not be used for a threshold of significance under CEQA.”

Englemann dismissed the widely expressed concern that focusing on LOS necessarily leads to wider, faster roads. “In many places, it's not even possible to widen roads,” he said, “so mitigations might include shuttle buses or multimodal efforts or any number of other things.”

Another objection that some planners have to requiring LOS analysis is that the process is cumbersome and often produces inaccurate results. Reams of data are required by LOS models, and the process includes many steps to reach a precise number. While the number may be precise, the assumptions in the underlying data are allowed to have a very high error rate.

Some planners think that measuring vehicle miles traveled (VMT) would be much simpler and produce a more accurate calculation, especially with recent technologies. Measuring VMT would be a more appropriate way to analyze bicycle improvement projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled “even if [they] increase automobile congestion,” according to the California Bicycle Coalition's official response to the OPR.

Official comments are due by the end of today to: guidelines@ceres.ca.gov