Last month, Streetsblog introduced a six-part series by Mark Vallianatos looking at how city leadership can start truly integrating land use and transportation in the six geographic zones he outlined: parks, hills, homes, boulevards, center and industry. First, he outlined the series and wrote about parks. Later, “The Hills”, “Homes Zone”, “Boulevard Zones” and "Centers" got their turn.

Each section includes a “ preferred mobility” that the land use and transportation networks should support, a description of the land type and Vallianatos’ prescriptions.

Vallianatos is a professor at Occidental College and the Policy Director of the Urban & Environmental Policy Institute, Board Member for Los Angeles Walks, and regular contributor to Streetsblog.

Without further ado…

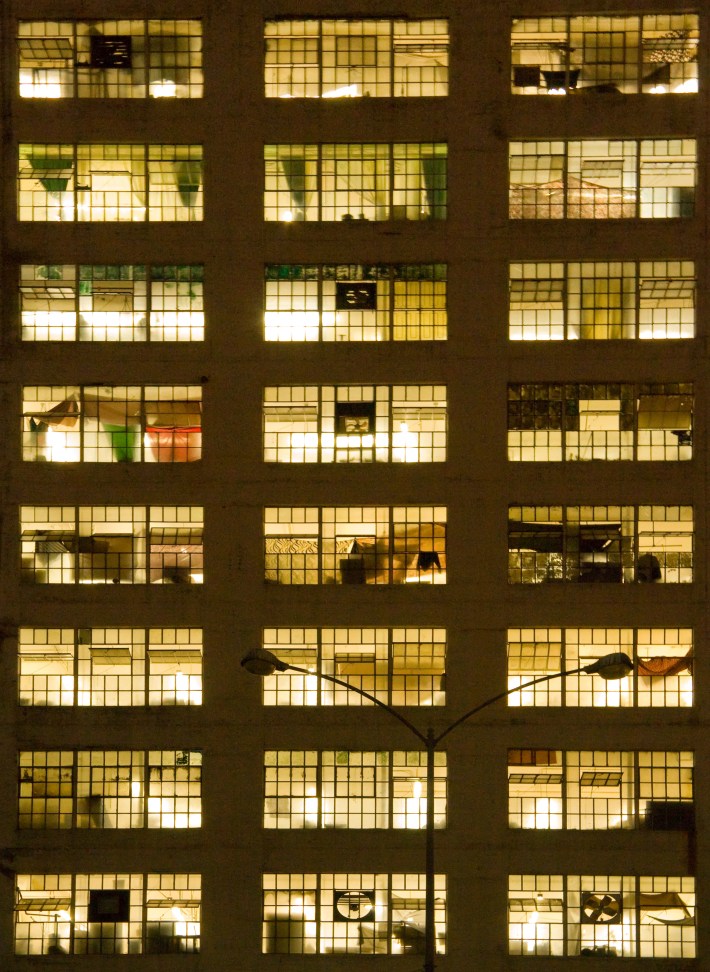

Industry

Preferred mobility: zero-emissions freight

“So many [people] unneeded, unwanted in a world where there is so much to be done… Once upon a time, visitors could take a guided tour and see how tires were made, just as today, they can take a studio tour and see how movies are made.”

Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself

The Industry zone refers to portions of Los Angeles zoned for manufacturing and other industrial activities. I will be considering how the products and inputs and waste of these sites are moved throughout the city and beyond and how industrial land uses can fit with the rest of the urban fabric. As I wrap up this series, thanks to Damien for running it on Streetsblog Los Angeles and to many colleagues, experts, advocates & my students for talking to me (and teaching me) about land use & mobility in Los Angeles.

Los Angeles has grown by producing improbable things: a Mediterranean climate in North America; oranges without seeds; pictures that move; distant water; oil from the ground; weapons for the sky; a new relationship between cars, people and places. These and other industries attracted millions of people to the Los Angeles region and helped shape the economy, built environment and transportation in and around LA.

In a previous post about single family residences , I implied that the house + car relationship was the dominant factor in giving Southern California its distinct, pioneering role in sprawl and auto-dependence. Industry created patterns in this sprawl. Historian Greg Hise used the metaphor of the magnet to describe how the region was planned as a multi-nodal area and how major industrial facilities attracted large scale residential developments.

As an example, Wade Graham in his contribution to the book Blue Sky Metropolis highlights how aerospace companies shaped the physical form of Greater L.A.

“The Big Six aircraft manufacturers, all of which had started out in tiny rented spaces in districts within a few miles of downtown Los Angeles, soon spread out to locations near outlying airports where there was room to grow: at Burbank, Santa Monica, Inglewood, and El Segundo… The postwar Los Angeles that emerged was a regional city, with its nodes sown from the principal aircraft plants and grown into surrounding, purpose-built communities: North Hollywood–Burbank–Glendale (Lockheed, Vega), Santa Monica–Mar Vista–Culver City (Douglas, Hughes Aircraft), Inglewood–Westchester–El Segundo (North American, Douglas El Segundo, Northrop), Downey (Vultee), and Long Beach–Huntington Beach (Douglas Long Beach). These spreading clusters traced a ring roughly fifteen miles in radius around Los Angeles City Hall, linked by an emerging system of freeways.”

As aerospace continued to thrive during the cold war, its locations leapfrogged further into the exurban fringes of Los Angeles, helping draw populations into Orange and Ventura Counties and the Antelope Valley.

Employment in manufacturing and related industries once fueled migration to the LA region and provided a pathway into the middle class. More than 10,000 industrial workers were arriving in Los Angeles every month during much of World War 2 and into the mid 1950s and early 60s half of the manufacturing jobs in the county were in aerospace. One of the great tragedies of life in Los Angeles over the past 40 years, referenced in the quotation that opens this piece, is that these good jobs in unionized heavy manufacturing sectors like aerospace, automobiles and steel diminished just as the region was becoming more ethnically diverse and workplaces were becoming more open to women and non-whites.

With the end of the cold war, durable goods manufacturing jobs in the Los Angeles – Long Beach – Santa Ana metropolitan area fell by 32 percent just between 1990 and 1994 and Former Mayor Richard Riordan explained wage declines by saying that we were no longer “subsidized by people around the world to build things to kill people.” Manufacturing is still the leading contributor to our gross regional product, but employment in manufacturing has continued to decline. According to Economic Modeling Specialists Intl, “352 of the 472 manufacturing subsectors classified by the U.S. Census Bureau have lost jobs since 2001 in Los Angeles” and manufacturing employment is down from over 800,000 in 2001 to 535,000 in 2012.

While employment in the logistics and transportation sector has made up for a small portion of these losses, the median hourly wage in the transportation sector is $13.05 and in the manufacturing sector it is $12.93, both significantly below the region’s $18.24 median wage.

From their heyday to the present, industrial land uses have also left a toxic legacy in Los Angeles. Petroleum extraction, refining and sales; power generation; manufacturing and goods movement have polluted groundwater, contaminated land, and emitted hazardous substances into the air we breath. After decades of intensive efforts to reduce air pollution in LA, there has been progress, but the areas is still ranked as having the worst ozone and fourth worst particle pollution in the United States.

The contamination, sounds, and smells of industry have made industrial land uses in Los Angeles undesirable neighbors for over a century. Battles over the right locations for and regulation of industry help explain why, to this day, manufacturing and warehousing is clustered along parts of the Los Angeles River. It is partly because early manufacturing relied on the river for power and to dump their waste into, and took advantage of rail infrastructure clustered near the river and downtown LA. But these clusters also exist because, in 1904, as residential areas rubbed up against industrial uses, voters (in one of the first ever use of the popular referendum) restricted slaughterhouses to two city council wards near the river, setting a pattern for exclusive industrial zones.

Research and advocacy around environmental justice have shown that low income residents are more likely to live in neighborhoods burdened by the cumulative impacts of multiple sources of pollution, made worse by other health and socioeconomic challenges. The state of California has created a California Communities Environmental Health Screening Tool “to identify California communities that are disproportionately burdened by multiple sources of pollution and most vulnerable to its effects.”

Putting my address into the mapping tool, I can see that the area where I live is considered to be in the top (worst) ten percent of zipcodes facing environmental health threats.

In recommending goals for Integrating land use and mobility in industrial zones in Ls Angeles, I’ve tried to juggle four goals. How to move products without poisoning people; how to preserve some land for industry jobs and economic activity; how to clean up industry; and finally, once industry is clean, how to reintegrate it into the fabric of the city.

- Temporarily preserve space for industrial land uses. The City of Los Angeles has manufacturing zones primarily clustered near the Port, The Los Angeles River, South of downtown, and in parts of the San Fernando Valley. However most of the city’s manufacturing zoning categories allow other commercial uses and some multi-family housing.

- As commercial and residential development increases in formerly depressed areas close to industry, there can be pressures to rezone manufacturing districts. In some cases it is appropriate to rezone for mixed use, dense buildings, especially close to transit or when the industrial uses in question are low job and low wage businesses. But it is also important to retain some space for industry and industrial employment. The city should temporarily designate some areas as industrial preservation zones but regularly reassess the need for such single use zones.

- Allow more flexible use of space by industry. Just as the City’s adaptive reuse ordinance for downtown office space allowed unused commercial space to be transformed into housing by granting more flexibility on parking, fire and structural rules, adaptive reuse policies for industrial buildings could allow older warehouses and industrial structures to be reused by newer industries. The City should allow new use without triggering high parking minimums and other hard-to-meet mandates. Environmental standards should not be waived.

- Clean up industry. As referenced above, low-income residents often face a higher than average burden of pollution from major sources of emissions like factories, refineries, railyards and freeways. Research in Los Angeles has also shown that common light industrial uses like gas stations and auto body shops are more frequent and cause more problems in some areas than is captured by government toxics reporting laws http://www.libertyhill.org/document.doc?id=202 . As a result, community organizations in Boyle Heights, Pacoima and Wilmington have collaborated on a Clean Up Green Up campaign http://cleanupgreenup.wordpress.com/ to address these hazards. A motion to find land use, planning and economic development policies to reduce pollution and attract green jobs to these neighborhoods passed the City Council in April 2013. Los Angeles should reduce pollution from all industries in all neighborhoods to speed the transition to a green economy. Stronger local, state and federal laws can help, as can clean industry incubators like the City’s cleantech corridor.

- Integrate industrial uses with other land uses. As cleaner technologies, stronger environmental protections and more creative use of industrial space evolve in Los Angeles, the need to preserve and segregate land solely for industrial uses diminishes. A mid term goal for the City should be to integrate as much manufacturing and industrial uses as possible into the fabric of the city through mixed use zoning. This would help reverse the negative land use impacts of separate use zoning and speed the shift that UCLA professor Stephanie Percetl has labeled from the “sanitary city” to the “sustainable city”.

- Require a rapid transition to zero emission transportation for large scale, inter-regional and international movement of products and materials. One of the LA region’s leading industries IS transportation. The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are the busiest and second busiest container ports in the United States. In 2009, the Ports accounted for 10% of particulate emissions, 7% of nitrogen oxides emissions, and 42% of sulfur dioxide emissions in the South Coast Air Basin. Imports and exports from the ports extend inland via trucks, highways, freight trains, railyards and warehouses. The pollutants emitted by ships, trucks, trains and yard equipment contribute to asthma, reduced lung development in children, cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and premature death. All of these links in the goods movement chain need to be made cleaner. The ports have adopted a clean air action plan and clean truck plan. California requires oceangoing vessels to use lower sulfur fuels and slow down as they approach shore and to turn off their engines for shore power (or adopt equivalent controls) when docked. But much more can be done to transition to a zero-emissions transportation system for goods.

- The Port of Los Angeles should create a system for on-dock ship-to-rail loading of containers with electrified rail transport to inland destinations. The Grid Project is one proposal along these lines (although I don’t have an informed opinion on its technical merits). This will reduce diesel truck traffic near the ports and eliminate the need for polluting inland railyards such as the proposed SCIG or the existing Commerce yard, the second most carcinogenic rail-yard in the state.

- Develop electric truck technologies before building a network of truck lanes. SCAG’s long range transportation plan http://rtpscs.scag.ca.gov/Pages/default.aspx envisions spending tens of billions of dollars to create truck only lanes on the 710, parallel to the 60, and on the 215 to allow imports to be moved inland and up to massive logistics centers in the desert. These lanes are supposed to be restricted to electric trucks sometime in the future, perhaps powered by overhead catenary lines. The RTP dedicates tens of millions of dollars to research on zero emissions trucks. The ratio (if not the exact amounts) of spending on clean tech versus new freeway/ truck lane construction should be reversed. Local governments should only construct a massive new truck freeway system (1) after electric truck technology is developed and is commercially available; and (2) after reassessing the need for new truck lanes following the implementation of electric on dock rail. As a starting point, the City of L.A. should support Community Alternative 7 for the potential expansion of the 710 freeway.

- Work at all levels of government to clean and eliminate diesel locomotives. Railroads enjoy partial exemption from local and state regulation, making it difficult to require pollution control technologies or to outlaw the oldest, most polluting engines. Los Angeles should advocate for the Federal government to give more local authority over pollution from rail locomotives, and for railyards to be regulated as stationary sources of pollution.

- Require cleaner, greener warehouses and trucks. The Los Angeles region has approximately 850 million square feet of warehouse facilities. As close as one can come to sprawl in a box, newer large warehouses are structures that are spartanly built; off limits to most human beings; accessed primarily by trucks. Warehouses are aimed at distant points: factories in china, railyards near the port, big box stores in Illinois, rather than connected to the fabric of life in the communities in which they are located. To reduce the pollution caused by trucks parked at or idling near warehouses; they should be electrified so that arriving vehicles can plug in rather than run their engines.

- The cost of researching and installing clean goods movements systems should be partly born by fees on shipping containers, which can be passed on from importers (the largest of which are major retail chains) to consumers around the country (unlike the health costs of current goods movement infrastructure, which falls on residents and workers near ports, railyards, freeways, and warehouses).

- Encourage local deliveries by zero emission vehicles. The use of trucks for local deliveries can impede traffic, block bike lanes, and create impediments for foot traffic due to extra curb cuts from loading docks. As portions of Los Angeles become more dense and as vehicle lanes are repurposed for buses, protected bike lanes and broader sidewalks, there will be less room for larger trucks. The City should encourage the use of smaller, electric trucks and cargo bikes for a greater share of deliveries. One way to encourage more nimble and clean delivery vehicles is to institute size, place and time restrictions on deliveries by trucks but exempt cargo bikes and some smaller, zero emissions vehicles. Zoning rules could also reduce or eliminate requirements for loading bays and docks for enterprises that maintained a fleet of small zero emission bikes or mini-trucks.