Although Metro has now concluded the latest round of outreach meetings on its $425M Vermont Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) plans, the agency is still accepting feedback on the project through today, December 20.

Plans to transform 12.4 miles of Vermont Avenue - the county's busiest bus corridor - have been in the works for over a decade. But the project is still behind schedule. The 2024 groundbreaking anticipated in the Measure M expenditure plan has since been pushed back; approval of the project by the Metro board is now expected in early 2025. The full project is not expected to be completed until 2028-2030.

Given both the number of years it's been in the works and the significance of the corridor, the project is also far less ambitious than many might have hoped.

Early re-envisionings of the corridor included center-running BRT and streamlined-looking vehicles described as "light rail on tires" (below).

But by 2018, Metro had settled on side-running BRT for Vermont, both to ensure its buses could be interoperable on all Metro lines and to avoid costly battles over driver convenience and parking.

The current plan calls for all-day dedicated bus lanes, 26 enhanced stations at 13 station locations (below), enhanced shelters and other passenger amenities (including enhanced lighting), bus bulbs extending the pedestrian space and shortening crossings, enhanced crosswalks, and pavement repair. Metro estimates it will boost bus ridership on the corridor from 36,000 daily boardings to over 66,000.

The most recent renderings - seen in the video below - show side-running BRT buses sharing intermittently red lanes with local buses, examples of the enhanced stations and bus bulbs, and a highly aspirational scofflaw driver-free experience.

It is not quite "light rail on tires."

Metro anticipates the project will shave 17 minutes off the 70 minutes it currently takes transit users to travel the length of the corridor.

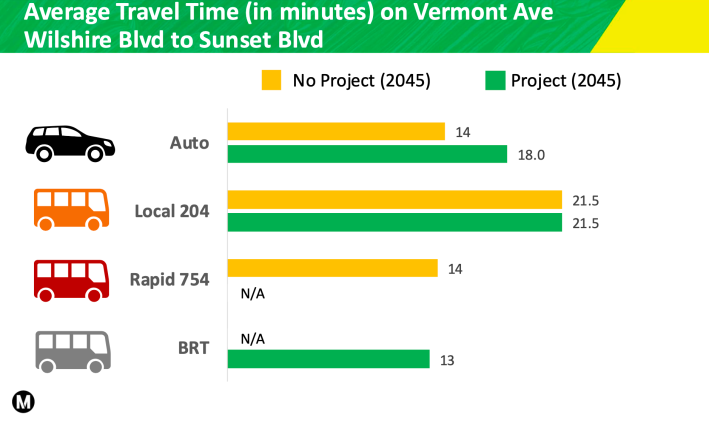

Those benefits will vary by segment, per Metro. Between 120th and Gage, for example, BRT users may gain five minutes over current Rapid 754 travel times. BRT users traveling between Gage and Wilshire could gain as many as 10 minutes on the current Rapid 754 average and travel at almost the same speed as a private car (25-26 minutes). The Local 204 route will benefit in that segment as well - a bus rider might see a savings of four minutes (making that trip in 35 instead of 39 minutes).

Although BRT users won't gain much between Wilshire and Sunset (below), the dedicated lane means they could potentially best a private vehicle by a full five minutes. Metro estimates suggest as much as eight minutes could be added to the travel time of drivers moving the full distance between Wilshire and Sunset, but Metro also anticipates that some of that traffic - up to 40 percent - will spill over to Hoover and Normandie.

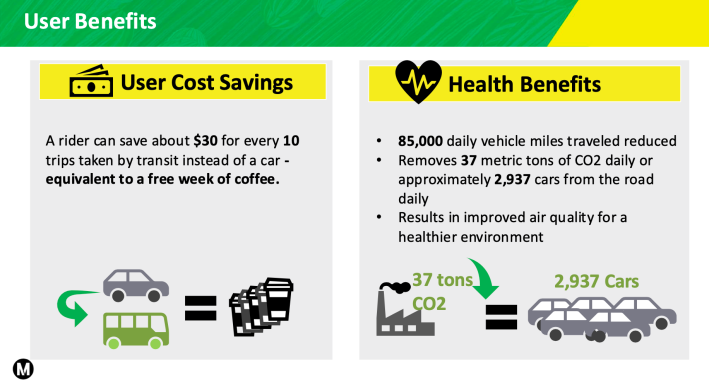

Perhaps considering the projected transit time savings were not substantial enough to encourage mode shift on their own, Metro emphasized the cumulative hours riders could save over the course of a year, the potential cumulative reductions in CO2 emissions by those that ditched their cars, and the number of coffees riders could buy with the money not spent on car trips (below).

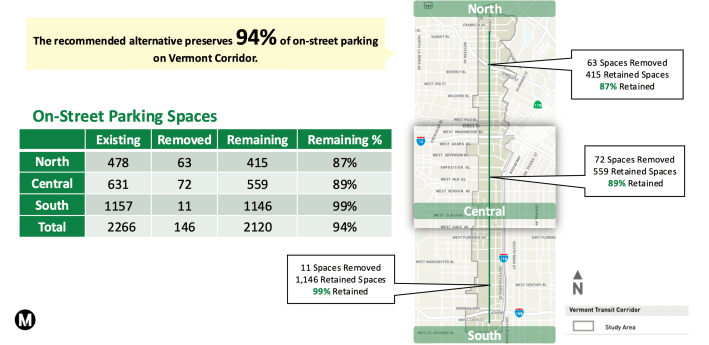

But, in response to feedback from local businesses, Metro was also quick to emphasize how little would change for drivers.

Specifically, 94 percent of the parking will be maintained along the corridor and drivers will still be able to use the bus lane for right turns and driveway access.

Also of note, Metro staff was clear that while the bus lanes will be labeled shared bus/bike, there would otherwise be no new infrastructure - and definitely no new protected lanes - for cyclists. The "significantly lower traffic volumes" in the dedicated bus lane, staff suggested, should enhance cyclist safety.

Meeting participants asked questions about bike lanes because the Mobility Plan 2035 does include a protected bike lane on Vermont, from Del Amo Blvd. to just north of Gage, and a striped bike lane from Gage all the way up to Los Feliz Blvd.

As SBLA reported earlier this year, advocates concerned about the quick-build nature of the BRT lane and omission of the bike lanes sent a letter asking Metro to uphold the promises of the Mobility Plan and provide a protected bike lane that ran the length of the project.

It wasn't their only ask. They also wanted to see pedestrian scrambles at high injury and bus transfer intersections, "non-hostile" shelters at stations, wait time displays, amenities that would create a more welcoming environment (trees, wayfinding, signage, the posting of the bus rider bill of rights, public water), the preservation of space for street vending, and the expansion of sidewalks where vending was in high concentrations along the corridor.

But cyclist safety, the advocates argued, was especially key to limiting conflicts between road users, reducing crashes, saving lives, and upholding economic justice, given the low-income status of so many along the corridor.

The advocates are correct.

While Metro is right to assume that some cyclists will feel confident enough to brave the bus lane, the reality is many of the low-income cycle commuters who currently ride on the sidewalk will not. Which means pedestrians and cyclists will continue to share cramped sidewalk spaces and cyclists will continue to be at elevated risk of being hit by drivers who do not watch for them while turning into driveways or onto side streets.

Yet that kind of analysis - and any other assessment of cyclist mobility along the corridor - is notably absent from the 210-page racial equity report Metro produced in order for the BRT project to qualify for an exemption from the environmental review process. In fact, the report only mentions the word "cyclist" twice: once in reference to the need to improve pedestrian and cyclist access to stops and once in reference to how that improved access will be measured.

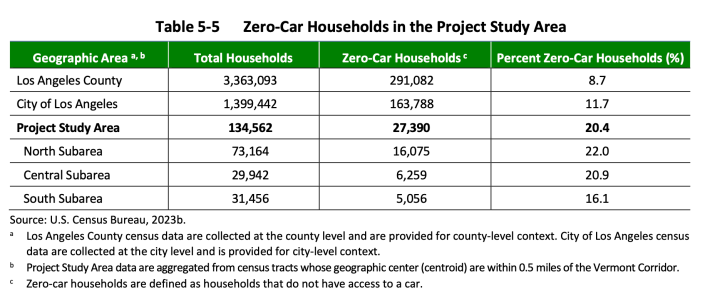

As SBLA has documented, Metro has a history of omitting planned bike facilities when making upgrades. But the extent to which cyclists are an afterthought along a corridor which sees some of the highest traffic-related crashes and deaths in the city and which Metro's own equity analysis indicates is flanked by disproportionately zero-car households (below) is troubling.

Per Metro, approximately 11.7 percent of the households in the City of L.A. are considered zero-car households, compared to 20.4 percent of the households in the Project Study Area. There will be no new bike infrastructure in the northern and central subareas, where car ownership is lowest. Find that table and a map of the zero-car households here (p. 5-13).

It could also get Metro in legal trouble.

In a saber-rattling letter directed to Metro Board Chair Mayor Karen Bass, the nonprofit advocacy group Streets for All warned the agency this past September that failing to implement the bike lanes mapped out in the Mobility Plan would put them out of compliance with the voter-approved Healthy Streets L.A. measure (which requires the city to install Mobility Plan elements whenever the city makes improvements greater than one-eighth of a mile).

Whether Metro will be able to take cover behind the Mobility Plan's own circumspect view of the city's obligations - the Plan calls the upgrades mapped out in its pages "a preliminary roadmap" to guide the city's choices and "not... a recipe book that must be followed to the letter" - remains to be seen.

During Monday's presentation, Metro staff seemed unfazed by the issue either way, saying the "constraints of the corridor" would not allow for new bike infrastructure... while reiterating how "crucial" it was to project stakeholders that parking was preserved.

Have any last-minute thoughts to share with Metro about the project? Send them in today: vermontcorridor@metro.net. Want to catch up on all things Vermont BRT? Check out Metro's project page for more.