There's a new report out that makes a compelling case for universal fareless transit in Los Angeles. This week, the nonprofit advocacy groups Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (SAJE) and the Alliance for Community Transit (ACT-LA) released their report The Road to Transit Equity: The Case for Universal Fareless Transit in Los Angeles. The report's lead author is Chelsea Kirk, SAJE's Director of Policy and Research, Building Equity and Transit.

The report gathers information on transit agencies that have implemented fareless. Who knew the L.A. County City of Commerce went fareless in 1960, and continued to operate fareless to the present day? Additional larger examples include Kansas City, Missouri, Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Olympia, Washington. The report compiles a lot of Metro information, much of it obtained through public records requests. It also tells the stories of L.A. transit riders through interviews with 113 bus riders in Vermont-Slauson, Boyle Heights, and Exposition Park; these riders' first hand stories tell the real-world impacts that transit and its fares have on people's lives.

Below are some highlights, though interested readers should check out the report itself, which weighs in at 51 pages, plus appendices.

Universal fareless transit makes fiscal sense

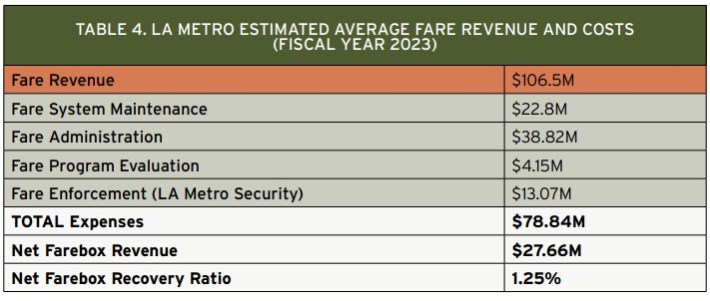

The report notes that for every fare dollar Metro collects, Metro spends $0.75 on the expenses of collecting and enforcing fares.

For fiscal year 2023, Metro expects to collect approximately $106.5 million from transit fares. The report "conservatively estimate[s] that close to three-fourths of that revenue—nearly $78.84 million—will be eaten up by the costs associated with running the TAP fare system" Further, the net fare revenue is likely lower as the authors were unable to account for all of the costs associated with collecting fares, and the total expenses don't include Metro transit policing contracts.

Given its massive countywide sales tax revenue streams, Metro relies on fare revenue much less than other large U.S. transit agencies. Metro's pre-pandemic 2019 farebox recovery ratio was 14.6 percent. (It was 4.8 percent in FY2022.) Compare this to New York MTA's 2019 farebox recovery ratio of 52.6 percent, or Bay Area Rapid Transit's 2019 ratio of 71.7 percent.

Sales tax accounts for half of Metro’s $8.8 billion capital and operating budget; fare revenue is expected to account for only 1.2 percent of the overall budget, and just 4.8 percent of the transit operations budget.

Universal fareless makes transit safer

There are many ways that fareless would make Metro transit safer.

Eliminating the need for fare enforcement would increase safety for Black and Latino riders by decreasing their interactions with law enforcement. The report states:

Numerous studies have shown how law enforcement exhibits bias against Black and Brown people, and L.A. Metro’s own data backs those findings up. An analysis of the agency’s citations and warnings by race in 2019 reveals that over 50 percent of all fare citations and warnings were issued to Black riders, even though Black riders represented only 20 percent of ridership. Fare enforcement can be a pretense that police and security officers use to act on biases and target Black and Brown people.

Eliminating fares eliminates the potential for that harm.

Fareless also eliminates conflicts between riders and operators. The report notes that, according to a transit worker safety study, "the majority of violent incidents on public transportation are assaults on bus drivers caused by fare disputes." Kansas City’s Zero Fare policy resulted in a 39 percent drop in crime during its first year, attributable to disputes over fares having been eliminated.

Additionally, safety increases as ridership increases. More transit riders means fewer desolate spaces and more people looking out for each other, in the “eyes on the street” sense noted by Jane Jacobs.

Fareless transit advances equity by reducing financial burdens on low-income Angelenos

63 percent of Metro riders have household incomes less than $25,000 per year. 40 percent of Metro riders earn under $15,000 per year. High housing and transportation costs combine to erode livability and quality of life.

Though Metro offers discounted fare programs, mainly its LIFE (Low Income Fare is Easy) program, its discount fare programs "have been unsuccessful in reaching all those who qualify for them." The report notes:

Enrollment in these [seniors, people with disabilities, students, and low-income] programs remains low despite the fact that L.A. Metro has spent millions of dollars in outreach and marketing efforts: qualifying riders are either unaware they exist, or they face barriers to applying, including not having the technology to apply online, not knowing where or how to apply in person, or not being able to complete the application process.

As UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies Equity Research Manager Adonia Lugo notes in the report's forward:

Given the clear data that the bulk of LA Metro’s riders are living with all the strain of economic struggle, going fareless would eliminate a tax on being poor in our region. Why continue nickel-and-diming the people who most need a break?

The report's executive summary takes it from there:

L.A. Metro has attempted to solve the financial burden of fares on their riders through fare capping and means-tested discount programs. These initiatives are not only expensive to run, but they also have low enrollment rates. And, ironically, if LA Metro successfully enrolled all those eligible for discounts, their earnings from fares would be even more negligible than they are now. In effect, the agency is spending millions of dollars to get the majority of its riders to pay less in fares. Why not just go fareless?