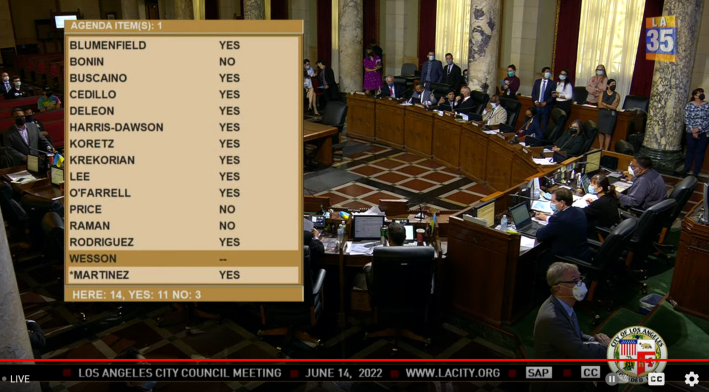

In a brief and anticlimactic session this past Tuesday, City Council tentatively* approved a controversial ordinance cracking down on so-called "bicycle chop shops."

[*Per council rules, an ordinance needs a unanimous vote to be adopted when first introduced. If it falls short, as today's vote did (below), the ordinance must be voted on again the following week, but only needs a majority approval at that time.]

The ordinance is one of several council has adopted targeting visible homelessness. At the end of May, for example, councilmembers moved to draft an ordinance banning encampments within 500 feet of daycare centers and schools. And just yesterday, they added a handful of locations in District 5 to the growing list of sites where councilmembers (via the anti-camping ordinance approved last year) have banned "sitting, lying, sleeping, or storing, using, maintaining, or placing personal property, or otherwise obstructing the public right-of-way."

The chop-shop policy is a bit different in that it targets people's means of transportation and, in some cases, their livelihoods.

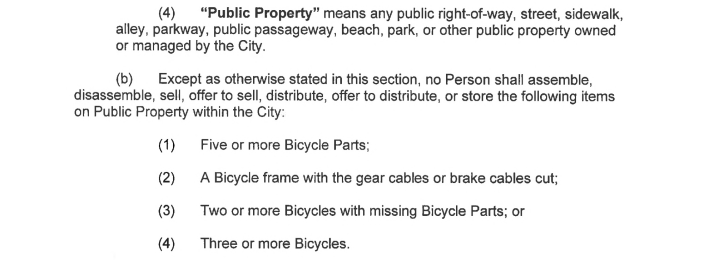

Similar to the policy in neighboring Long Beach, the new ordinance [PDF] will prohibit the repair, sale, and storage of bicycles and bicycle parts on public property by people who have amassed five or more major bicycle parts (handlebars, wheels, forks, pedals, cranks, seats, or chains), a frame with the cables cut, two or more bikes with missing parts, or three or more bicycles. From the ordinance:

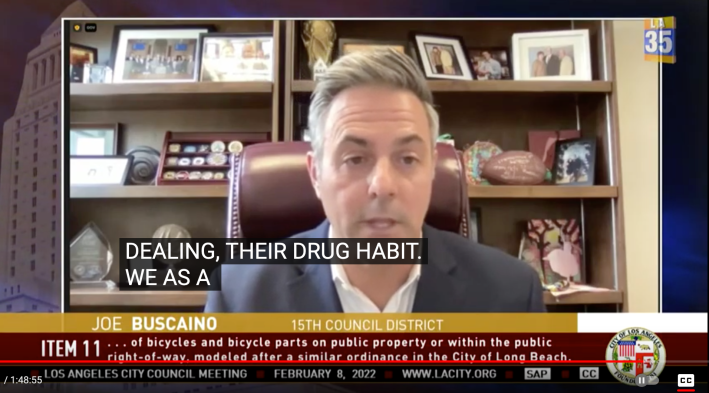

First proposed by Joe Buscaino back in October of 2021, the motion [PDF] was part of Buscaino's larger effort to position himself as The Only Candidate for Mayor Prepared to Reclaim Streets from Utter Lawlessness.

He had launched his "broken sidewalks"-themed campaign a few months earlier, in June, with a kickoff event calling attention to the notable growth in homelessness in Venice (while also trying to stick it to that district's more community-care-oriented councilmember, Mike Bonin). Against a grim backdrop of "Say No to Encampments" and punctuation-free "Save Us Joe" signs, Buscaino declared the need to use every available method, including that of law enforcement, to get the people he categorized as shelter-resistant off the streets. [Click through to the thread of L.A. Times' Benjamin Oreskes to listen to those talking points; see the LAT story here.]

Here we are in Venice and it’s clear how @JoeBuscaino plans to run for Mayor. pic.twitter.com/9r6uqINu6T

— Benjamin Oreskes🦅 (@boreskes) June 7, 2021

Three weeks later, during the debate on L.A.'s anti-camping ordinance in council, he doubled down on that approach, imploring his colleagues to support his amendment instituting consequences - e.g. arrest - for those who "refused" an offer of shelter. [Watch that speech here.]

They declined to follow his lead.

Undeterred, Buscaino decided to pursue that goal via ballot measure. Then he moved on to more attainable targets, like the "chop shops."

In introducing the motion, he argued that cracking down on the proliferation of sites where bicycles were disassembled for parts and resold would help deter bicycle theft.

Buscaino offered no data to support the claim that the bikes seen at encampments were indeed stolen, either in the motion itself or in his remarks to council. Nor did he appear interested in attempting to distinguish between people doing legitimate scavenging and repair work to help keep themselves and their unhoused and lower-income neighbors rolling and those engaged in actual criminal activity.

Instead, he went on the offensive, declaring he was “miffed” that some of the councilmembers objecting to his motion had also objected to the anti-camping ordinance and seemed intent on "sending a message that anyone anywhere in the city can block any public right of way that belongs to the public" and that "thieves have free rein.”

He also pushed back at concerns voiced by councilmembers Bonin, Marqueece Harris-Dawson, and Nithya Raman that the motion was too broad and could impact anyone - but lower-income or unhoused Black and brown people, in particular - whose bike(s) had broken down or who couldn't prove that their bike(s) were theirs.

“This ordinance does not criminalize homelessness,” Buscaino declared. “It criminalizes conduct that is the direct result of [people] failing to support their drug habit. We as a city need to stop enabling drug addicts.”

City attorney inserts minimal protections against harassment

Although Buscaino had been dismissive of the dissenting councilmembers' concerns, the city attorney had been less so.

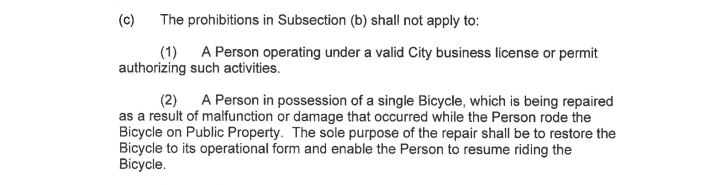

The draft ordinance that subsequently went before the Public Works and Public Safety committees included a section listing who the ordinance would not apply to. Namely, people with permits or licenses to do repairs or someone whose bike had broken down and was working on it to get it back up and rolling so they could continue on their way.

The provision appears to be a direct response to Harris-Dawson's pointed critique. The councilmember had spoken at length about having grown up riding secondhand bikes with his friends as a youth, and how difficult it would have been for them to prove they owned their bikes when those bikes inevitably broke down. He did not want to see the ordinance effectively grant law enforcement greater license to hassle youth of color in similar circumstances about where they had gotten the bikes or the parts they were tinkering on.

“It’s very different when you have to think about the problems that will be created by – and the jeopardy that you’ll be put in by – a policy if you’re someone who might be targeted,” Harris-Dawson had told council. An ordinance that categorized “anybody fixing a bike on a street that can’t prove it’s theirs…[as] a criminal” is “absolutely outrageous and beyond the pale.”

The inclusion of a broad clause exempting people repairing their own bikes differentiates it from the Long Beach ordinance, which required people to have proof of ownership of the bicycle being repaired. But it is unfortunately not sufficient.

Most people do not know how to do even basic repairs on their bikes. Better off cyclists have the means to visit brick and mortar bike shops to get the assistance they need. Lower-income commuters often do not - either because there aren't any in their neighborhoods or they don't have the cash on hand to cover a repair. A popped tire alone could cost them $8 at a shop, which is a lot for people who live hand to mouth. And new parts may be out of the question. So when they have a break down in the street, they may take their bikes to the very folks that the ordinance is targeting. Especially if their bikes are in constant need of repair because they weren't able to afford a good bike to begin with. Meaning the ordinance still has the potential to sweep up both housed and unhoused folks just looking to keep rolling as well as those who are serving those communities (like César, whose van is seen at the top of the article).

That said, the clause was sufficient to get a nod from Harris-Dawson, who voiced no objection when the draft ordinance went before the Public Safety committee on May 4.

And the ordinance did inspire some supportive - if bizarre, confusing, and poorly articulated - pontifications from Mitch O'Farrell during the May 25 Public Works committee meeting. [O'Farrell, it should be noted, is currently running for re-election (he is slightly behind challenger Hugo Soto-Martinez, per the most recent vote tally) and, like Buscaino, has made addressing visible homelessness a pillar of his campaign efforts.]

Quoting from author Sam Quinones' The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth, a controversial book that blames the rise in both homelessness and police shootings on P2P meth coming in from Mexico, O'Farrell attempted to make the case that bikes were a sign of meth usage.

By that logic, the proposed crackdown could be seen as a tool for addressing addiction among the unhoused. However, such a framing also broadens the net that the ordinance would cast by lumping drug users scavenging for parts in with organized theft rings - the supposed target of the law.

"Nothing indicated meth-induced homelessness like a bicycle fixation," O'Farrell read from Quinones' tome. "Stolen bikes went hand in hand with the drug. Bikes allow for mobility for people without cars. P2P meth seems to promote the hoarding of junk, which is why tent encampments are so often full of bizarre collections of seemingly useful stuff. Bikes allowed a user to travel greater distances looking for junk. In the homelessness-P2P meth world, bikes became currency, easily exchanged for dope. Bike shops popped up across Los Angeles as both tents and meth spread."

Unfazed by having effectively just advocated for the criminalization of owning and/or riding a bicycle, O'Farrell then concluded by thanking Buscaino for proposing the ordinance, saying it would help the city get at the root causes of why people were living in the streets.

It remains to be seen what enforcement of the ordinance will look like in practice.

During the Public Works meeting, the city attorney's office clarified that if people were cited under the ordinance, their bikes/parts would not be confiscated. Bikes/parts would only be confiscated during an arrest, in which case they would be booked as evidence.

Given the difficulty of proving bikes were stolen (and the hassle of gathering up and storing so much property), it would seem likely that arrests would only be made in the most egregious of cases. Meaning the ordinance may instead be leveraged to encourage people to move along in response to citizen complaints or as an excuse to conduct searches for other contraband that people could then be prosecuted for. None of which addresses the issue that supposedly inspired the ordinance: bike theft.

Buscaino clearly did not see it that way. In his closing remarks at council yesterday, he declared that "This ordinance will give LAPD a necessary to tool to reduce bike theft, clean up our streets, and improve the quality of life for residents across the city."

The victory came too late for his campaign, however. He bowed out of the mayoral race in mid-May after stalling out in the polls at just one percent.

_________

Find the ordinance here. Read our past coverage of the ordinance here.

Updated: Story has been updated to clarify the Long Beach ordinance required individuals whose bikes had broken down to produce proof of ownership.