Last Tuesday, May 24, while several of his deputies were testifying before the Civilian Oversight Commission (COC) about the long-standing scourge of deputy gangs within the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department (LASD), embattled sheriff Alex Villanueva was busy attempting to redirect public attention toward one of his favorite targets: the "woke" Metro Board.

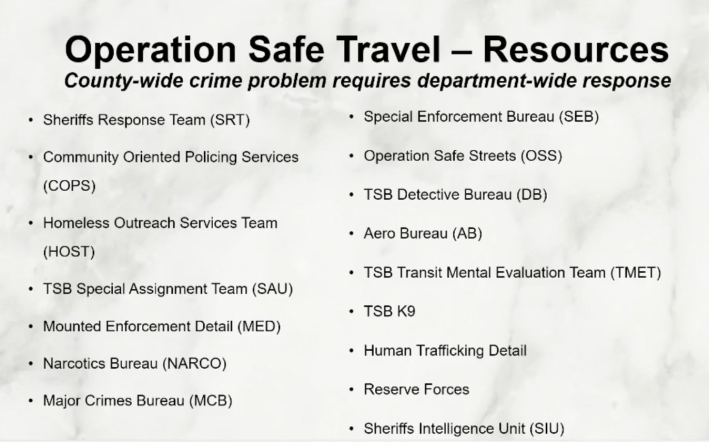

In yet another grievance-fueled briefing decrying what he claimed to be the board's indifference to matters of law and order, Villanueva announced plans for what effectively amounts to a massive sweep of Metro trains and platforms using everything from LASD homeless outreach teams (HOST) to the Aero Bureau to the Sheriff's Intelligence Unit to the Mounted Enforcement Detail.

The goal?

To expel every last one of the approximately 5,700 unhoused people estimated to be riding and/or taking shelter on Metro from the system starting on June 1.

The reason?

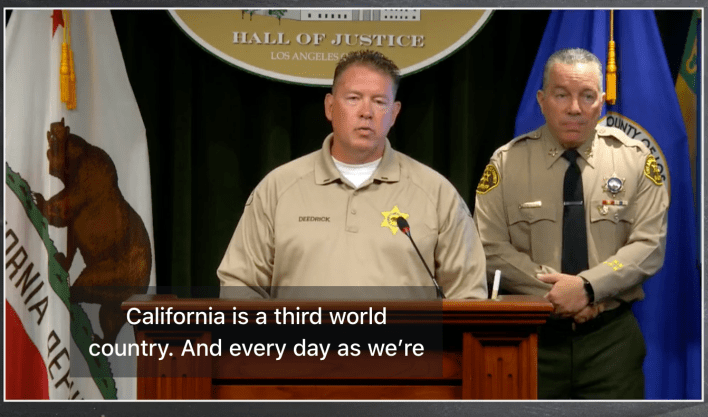

The links Villanueva, Captain Shawn Kehoe, and Lieutenant Geff Deedrick (head of HOST) all claimed exist between unhoused people and violent crime.

At least, on the trains.

"The biggest problem we have right now," Villanueva declared, is that people who "are actually using the trains for their intended purpose - for travel" and the unhoused population are "colliding with deadly results."

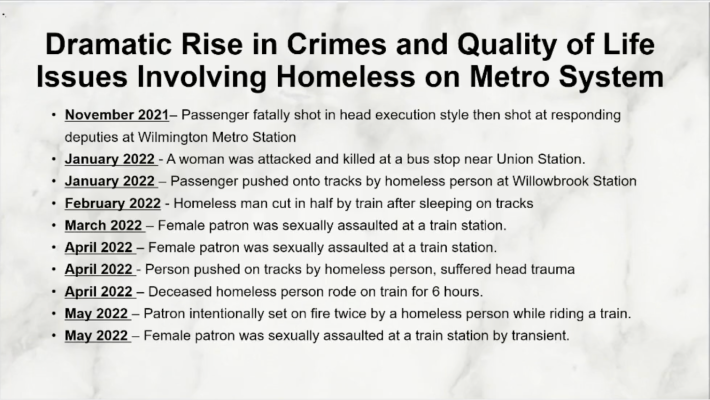

Then, after listing off several high-profile crimes on trains or platforms that he said had been committed by the unhoused, he concluded that “this is just illustrative [that] when you have that large of a population of homeless people on the system, bad things will happen.”

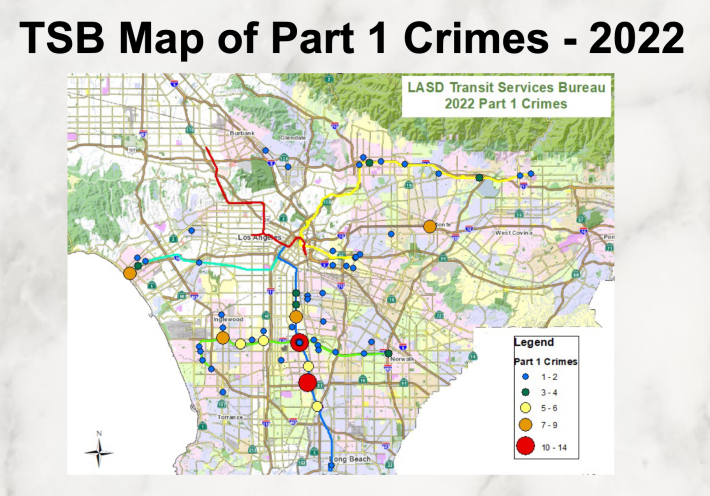

“You can see how crime follows the track system,” he said while pointing to a slide mapping crime along the train lines (above).

When pressed by reporters for data indicating how many serious crimes had actually been committed by unhoused people, however, Villanueva immediately waffled.

He invited Kehoe to "take a wild stab" at the question, but Kehoe could only say they didn't have "exact statistics."

Kehoe then referenced the powerpoint slide Villanueva had shown earlier (below) and said that the crimes listed there had been perpetrated by homeless people. That list of ten events includes the "crimes" of expiring on the system and of being hit by a train after falling asleep on the tracks.

Given that, per Metro’s last count, the majority of the unhoused - nearly 75 percent, or 4,168 people - are found on Metro buses (vs. 1,571 on the trains), Villanueva's prioritization of the trains is noteworthy. Even the LASD press statement mentions the Operation Safe Travel hotline is for train passengers, leaving bus riders and operators to kick rocks, apparently.

Perhaps that is because bus operator assaults are a long-standing concern and can't easily be pinned on mentally ill or unhoused people - making them less useful during the election cycle.

Villanueva has made banishing visible homelessness a pillar of his re-election campaign. So much so that, as reported in the L.A. Times, a recent lawsuit alleges LASD resources are being used to target homelessness in order to help Villanueva secure both campaign funds and votes.

As people continue to be squeezed out of public spaces, the trains and platforms where folks have taken refuge provide him with the campaign imagery he seeks, if not the proof of criminal activity he was hoping for.

Case in point, the most memorable part of the video of his recent trek to Hollywood on the Red Line - a trip intended to showcase the "mayhem" Villanueva claims Metro has unleashed but instead featured him dramatically intoning, "Why did I have to see the mentally ill and the drug addicted sprawl out over the benches on the trains?" - was a wee possum on a pole.

_________

Villanueva quietly walks back an ultimatum

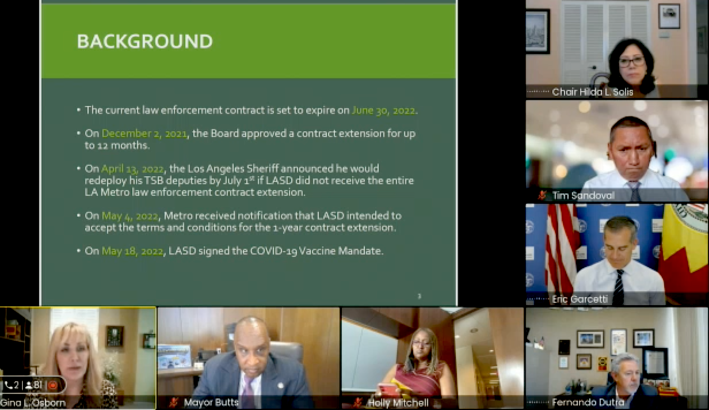

The threat to flood the system with deputies represents a complete retreat from the saber-rattling ultimatum Villanueva had issued to Metro this past April.

At that similarly grievance-fueled briefing, Villanueva had railed that Metro was “degrading the capacity of law enforcement to address crime in a proactive manner” by having shifted responsibility for most code of conduct enforcement to Metro's Transit Security Guards (TSOs). Then he had declared that if the sheriff’s department was not reinstated as the sole agency responsible for policing the full Metro system - including code of conduct violations - as of July 1, he would reassign his deputies to other areas, effectively abandoning Metro.

Of course, Metro had switched to a multi-agency policing contract back in 2017 largely because of how poorly LASD had performed under the single-agency contract. Most notably, year after year, they had failed to curb the rise in the very kinds of crimes Villanueva seems to feel only he has the will to address now. [For a more thorough listing of LASD's prior failures, click here.]

Though the shifting of responsibility for code of conduct violations to TSOs is more recent - it was written into the extension of the policing contract this past January - it, too, has its roots in LASD's troubling practices. Civil rights complaints about deputies' disproportionate citation and arrest of Black riders for fare evasion and other minor violations had prompted Metro to begin shifting fare enforcement to TSOs back in 2017.

When a review of citation data from 2018-2020 found Black riders continued to be disproportionately cited for fare evasion, Metro added the modification stripping code enforcement duties from LAPD, LBPD, and LASD into the January contract extension. The contract modification and extension buys Metro a year to complete the process of reimagining public safety already underway. In the meanwhile, TSOs can and do call on armed law enforcement for assistance when interactions escalate. LAPD, LBPD, and LASD, in turn, are expected to focus on penal code violations, illegal activity, and violent crime.

Still, if Villanueva had had any intention of following through on his ultimatum, it could have left Metro in quite a lurch.

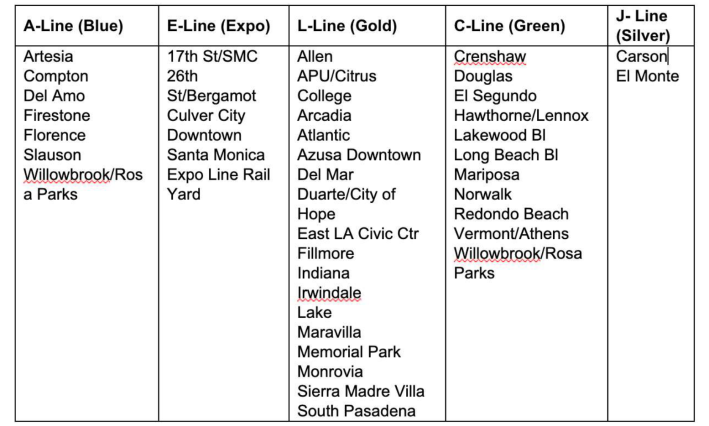

The sheriff provides a number of services (responding to 911 calls, patrolling buses, providing Mental Health Evaluation Teams (METs), etc.), all of which Metro relies on to respond quickly to emergencies and to limit interruptions to transit service. LASD also patrols the trains and stations listed at right.

That didn't keep boardmembers from voicing their dismay at Villanueva's lack of regard for the safety of Metro passengers, however. Or their annoyance at the obvious grandstanding.

Boardmembers subsequently moved to set up a contingency plan to ensure the system would be covered if needed. At the May 26 board meeting, Chief Security Officer Gina Osborn sounded pleased to report LAPD had been more than ready to meet and exceed the contract expectations of the sheriffs. A staff report also notes that more than 25 police chiefs from around the county met with Metro to learn more about the sudden potential contract opportunity.

That staff report also indicates that Villanueva did not actually send his ultimatum in writing to Metro until April 27 - a full two weeks after his headline-making briefing.

In response, Metro had fired off a letter giving Villanueva until May 15 to turn in a demobilization plan "detailing how LASD would return Metro vehicles and equipment and vacate the office spaces currently occupied by LASD."

He backtracked just a few days later.

On May 4, he notified Metro he would be accepting the terms - including the modifications to code of conduct enforcement policy - extending the current multi-agency policing contract for another year. Then, on May 18, he finally signed the COVID-19 vaccine mandate. [Notably, he had balked at the vaccine mandate last October, claiming there was no justification for it and that as much as 44 percent of his workforce might walk off the job over it.]

_________

No plan, just (aggro) vibes

With those issues settled, the board reluctantly turned to Villanueva's new threat to swarm the system and find ways around what he described as "illegal" elements of the code of conduct enforcement policy he had just signed on to.

Metro had reached out to Villanueva in February specifically to request that HOST and MET assist Metro in enhancing safety and security on the system, but the May 24 press briefing had been the first and only notice the board had gotten regarding this surge. Which left them questioning whether these plans were real or another "stunt," as boardmember, L.A. City Councilmember, and frequent Villanueva target Mike Bonin put it.

“Plans” might be too generous of a word.

During the briefing, Villanueva et al confirmed only that LASD would be "leveraging the department's resources" for "high visibility patrols," engaging unhoused people on the trains, and finding laws they could enforce as part of an "early intervention" effort to "meet people that [are] in some form of crisis before it's escalated to the point where people are being harmed."

No timeline was provided - there would be a surge for “as long as [LASD] can sustain it.” Once the system was “back under control,” LASD would “tone it down.”

There was no clarity on whether Villanueva would actively encroach on other law enforcement agencies' jurisdictions (as he has done in Venice Beach, for example); he said only that he would be speaking with the Chiefs of Police Association and that he was "hoping that they'll take up the same posture themselves."

And despite having name-checked LASD's Major Crimes Bureau, Narcotics Bureau, and Special Enforcement Bureau (responsible for handling high-risk tactical operations involving barricaded suspects, hostage situations, and high-risk warrant services as well as security for visiting dignitaries and politicians), Villanueva made no effort to explain how those or any of the other bureaus named would be deployed.

This was the Special Enforcement Bureau in action on a train on June 1, by the way:

Earlier today @SEBLASD conducted emergency response drills involving an active shooter. Participating in today’s drill were @TransitLASD Deputies, @Inglewood_PD and @LACOFD on the downtown Inglewood @metrolosangeles rail station. pic.twitter.com/3WqKpbLDsA

— Alex Villanueva (@LACoSheriff_33) June 2, 2022

Lt. Deedrick did give a brief presentation regarding HOST's proficiency at "rapport building," "maximizing de-escalation," and collaborating with civilian partners to assist the unhoused, but he was speaking more broadly to the ongoing work HOST does at encampment sites.

He offered no insights on how HOST and these other bureaus - which presumably lack specialized experience and/or training in mental health, etc. - would engage individuals that were in constant motion or that presented more complex mental health profiles than those at fixed encampments.

Nor did he or Villanueva speak to how and whether this surge will intersect - or possibly compete - with the efforts of the new 10-team psychiatric mobile response pilot Metro and the Department of Mental Health launched just last week. [The three-year crisis response program has been in the works since last October; learn more about it at The Source.]

Instead, Villanueva reiterated his claim that Metro’s code of conduct policy was an "enormous liability" and a hindrance to crime prevention.

The lack of any kind of articulable blueprint for how to identify and move 5,700 individuals is rather astonishing.

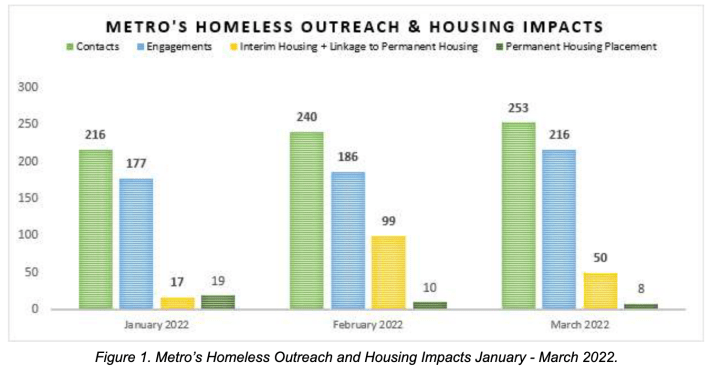

Quarterly updates from Metro’s street-based homeless outreach partners, People Assisting the Homeless (PATH), offer a window into just how difficult it is for specialized providers to move the population on Metro into stable housing.

Trust-building work requires time, and it can take between 6 months and a year to move someone into the housing pipeline. The availability of appropriate resources can sometimes be as much of an issue as people's willingness to accept a referral. COVID outbreaks over fall/winter continued to limit the availability of some interim housing options early in the new year, impacting the number of people PATH could move into beds in the first quarter of 2022 (seen above).

The quarterly reports also indicate that the success rate of LASD's Transit METs - who, along with LAPD's HOPE and LBPD's QOL teams, provide outreach during the hours that PATH workers are not on the system - is significantly lower than PATH's.

Of the 2,348 contacts LASD made with individuals who were reportedly unhoused or in crisis between September and November of 2021, for example, just 12 accepted referrals to housing or service providers, and only 13 were ultimately housed (either temporarily or permanently via shelters, motels, V.A. housing, hospitals, medical facilities/resources, family reunifications, transitional/long-term housing, or detox).

The TMETs had more success between January and March of this year: of the 1,630 contacts made, 44 accepted referrals and 55 were temporarily housed. But that still suggests there will be a massive gap - potentially of thousands - between the number of people LASD will contact during this surge and the number whose situations can easily be resolved.

What then?

Villanueva did not repeat last year’s threat to forcibly move or arrest unhoused people who didn’t move (off Venice boardwalk) fast enough. But he was also adamant that removal was his goal.

Deputies would start by checking to see who didn't get off the train at terminal points. Unlike the Metro security staff, who Villanueva complained "stepped over the bodies" of sleeping unhoused people, he said LASD "will definitely remove everyone from the trains at the end of every line...and platforms."

The accompanying press statement was both less informative and more alarming. It declared that step one of the "multi-layered approach" aimed at removing unhoused people from trains and platforms will be to remove unhoused people from trains and platforms.

It does not say where they are expected to go.

As for the Red Line possum, however, he can apparently stay where he is.

"God bless him," said Villanueva. "You know, hopefully he's alright."

_________

Watch the full May 24 press briefing here. We'll be tracking the surge on the trains in the coming days. Follow me on twitter for updates: @sahrasulaiman