In the wake of a pair of horrific shootings in Buffalo, N.Y. and Uvalde, Texas, the New York Times republished an updated version of a 2017 essay from Nicholas Kristof which urged lawmakers to use the "spectacularly successful" history of U.S. automobile regulation as a model for officials to finally take meaningful action on gun violence.

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of America's traffic violence crisis, though, would strenuously disagree — because the auto industry and the gun industry are both in dire need of far more aggressive safety reforms than they have now.

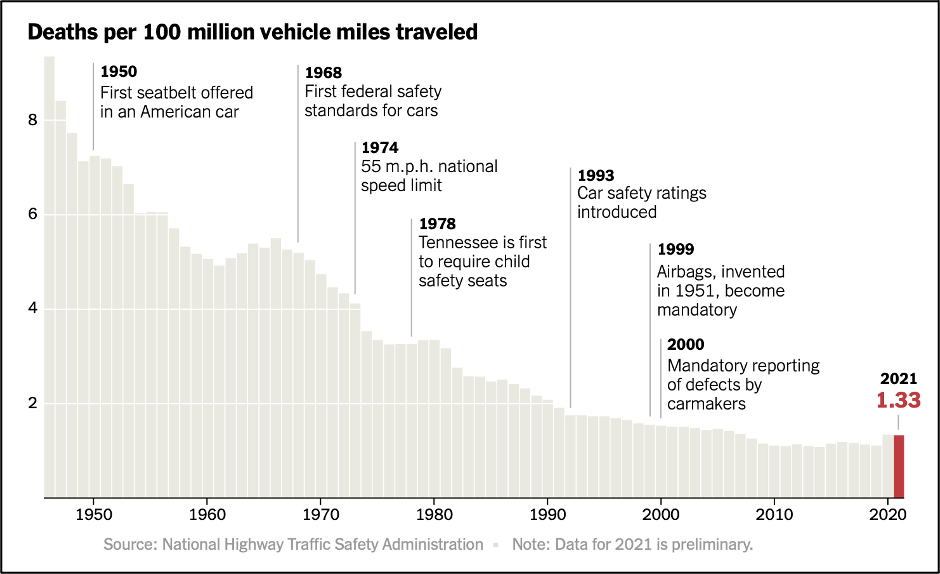

Let's be clear: every remotely credible expert agrees with Kristoff that systemic solutions, like the ones he outlined in his article, are the only real path to end gun violence in America, just like they agree that transportation leaders have made critical strides through regulation to save lives. The creation of mandatory vehicle safety standards like seatbelts and airbags, safety ratings programs to encourage automakers to compete for the dollars of safety-minded consumers, and a patchwork of state and local traffic and licensing laws have all helped cut the nation's per-mile crash death rate today to one-10th of the level it was in 1945. When Kristof first wrote his article, getting into a car in the United States was pretty much as safe as it had ever been in history.

That doesn't mean it was actually safe, though — particularly relative to the countries that we consider our peer nations. And it still isn't today.

Despite the vehicle safety improvements and policy efforts that Kristof lauds, America still has among the highest rates of car crash deaths in the industrialized world. (And for the record, we also have among the highest rates of car ownership in the world, so we have no idea what Krisof is talking about when he refers to America's successful efforts to "limit access" to cars in his article.)

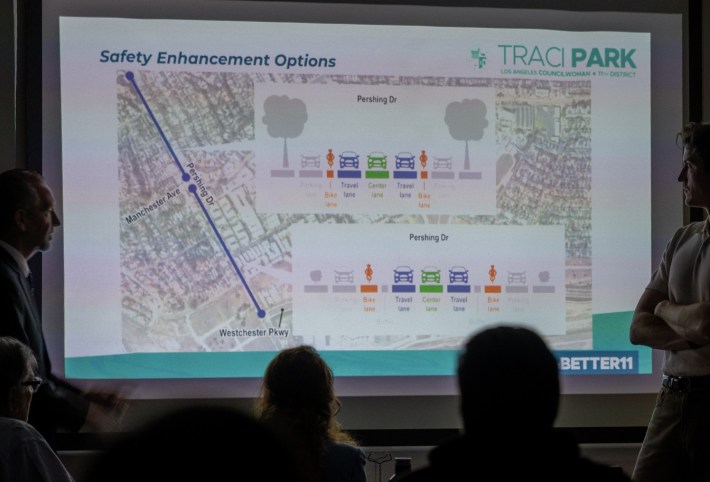

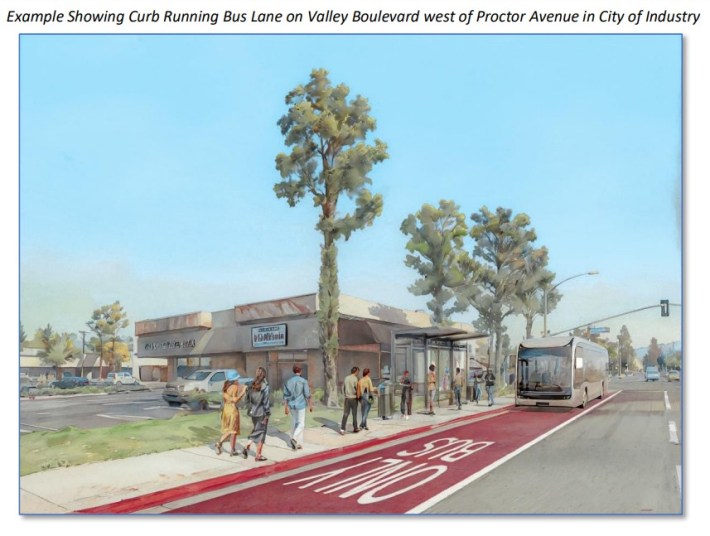

That's in large part because the United States has been alarmingly slow to adopt the Safe Systems approach that has driven traffic violence down to historic lows in virtually every country that's embraced the philosophy, missing out on years of improvements not just to car design and licensing laws— neither anywhere near as comprehensive as the Times implies, by the way — but to road design, road speeds, equitable enforcement, and post-crash care.

The U.S. DOT formally adopted that safety approach earlier this year, and stated for the first time in the nation's history that the only acceptable number of crash deaths is zero — but not before nearly 43,000 lives had been lost on U.S. roads in 2021 alone.

Even as evidenced by the updated version of Kristof's own article, America's dominant approach to safety hasn't resulted in across-the-board crash death declines.

In both 2020 and 2021, U.S. car crash deaths increased, a phenomenon experts attribute to an increasingly large proportion of dangerous cars in the vehicle fleet, piloted by drivers who found themselves on dangerous roads designed for speed over safety — roads that became even more deadly by the absence of traffic jams during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, rates of speeding and reckless driving soared, and deaths did, too — a trend which would appear far more dramatic in this chart, had the Times data department not included the decades when drivers were routinely impaled by their own steering columns for comparison.

Countries like Germany and Japan, meanwhile, have recorded some of their least deadly roadway years ever during COVID, because they'd implemented a broad range of transportation safety reforms before the pandemic upended the world.

Even for those who would discount the first two years pandemic as outliers, though, U.S. roads still aren't getting as safe as Kristof's article suggests. Some experts believe that highway engineers have undersold the scale of America's roadway crisis by calculating death rates based on vehicle miles traveled — something Americans log far more of than most other industrialized nations, and whose numbers go up every year — rather than by population, which may be a better metric to understand the scale of the tragedy for real communities.

Seen through that lens, total car crash deaths per capita have actually increased in four of the last 10 years, even as roadway death numbers overall seemingly plateaued.

The real horror hidden in America's traffic violence stats, though, is its disproportionate impact on people outside cars.

By sheer numbers alone, pedestrians, cyclists and other people traveling outside vehicles have increased 57 percent since 2009, reaching their highest level in 40 years in 2021. Vulnerable road users' per-capita death rate, meanwhile, has increased 33 percent between 2009 and now.

Experts say that's in large part because many of the very same vehicle safety improvements that Kristof praised in a 2014 op-ed comparing auto regulation to gun regulation had the unfortunate side effect of killing people that motorists hit. Because neither federal vehicle safety standards nor federal vehicle safety ratings require automakers to prove their vehicles are unlikely to kill pedestrians and cyclists in the event of a crash, car manufacturers are typically rewarded for building heavy, armored vehicles that can overpower any obstacle they may impact — even if that obstacle is the body of someone's child.

Shortly after the New York Times re-published Kristof's article — and just days after the horrific murder of 19 children and two adults in Uvalde — Axios reported that gun deaths had become the leading cause of death among people under 19, narrowly outstripping automobile deaths, which have long topped the list.

It was not because car travel got safer for children as gun deaths soared. Crash deaths among minors rose, too.

It was not because America's dominant approach to transportation safety had delivered yet another year of incremental but important successes, particularly not for the most vulnerable segments of the traveling population.

The first time Kristof suggested that gun control advocates follow the playbook policymakers had developed to control the auto industry, he praised Americans for refusing to simply blame individuals for systemic problems it is well within our power to solve:

"We could have said, 'Cars don’t kill people. People kill people,' and there would have been an element of truth to that. Many accidents [sic] are a result of alcohol consumption, speeding, road rage or driver distraction. Or we could have said, 'It’s pointless because even if you regulate cars, then people will just run each other down with bicycles,' and that, too, would have been partly true.

Yet, instead, we built a system that protects us from ourselves. This saves hundreds of thousands of lives a year and is a model of what we should do with guns in America. ... These steps won’t eliminate gun deaths any more than seatbelts eliminate auto deaths. But if a combination of measures could reduce the toll by one-third, that would be 10,000 lives saved every year."

But like Kristof himself in these deeply misinformed paragraphs, America never really stopped believing that individual drivers are ultimately to blame for the traffic violence epidemic, even as we've half-heartedly chipped away at the death toll with our limited box of tools. And we've done this despite a mounting consensus among experts that virtually every individual error committed on our roads springs from a systemic root.

And also like Kristof himself, America has never truly accepted the idea that car crashes, like gun deaths, are something we can end — not just "reduce" by a mere third, leaving tens of thousands to die and hundreds of thousand of loved ones to mourn. To do that, though, we need a radically new approach that addresses every system of violence upon which this country is founded, including white supremacy, systemic racism, the carceral state, a frayed social safety net, and so much more. These things touch America's traffic violence crisis, too — and most transportation leaders' playbook to confront them is, so far, woefully incomplete.