In early February, the L.A. City Department of Transportation (LADOT) quietly released its 2021-2023 Strategic Plan Update. It's a glossy document full of high-production-value photos and high-minded goals. But the plan sets frustratingly weak commitments to improving L.A.'s deadly streets.

The plan is emblematic of LADOT's decline under Mayor Eric Garcetti and LADOT General Manager Seleta Reynolds. Garcetti fancies himself a climate champion. Reynolds was recruited to LADOT as an advocate for pedestrians and safe streets. But this new Strategic Plan sets the sights set so low it might was well be a white flag of surrender to the forces of motordom.

It's not entirely Garcetti and Reynolds' fault. When LADOT had planned modest steps toward safer streets, the agency's efforts were frequently blocked by city councilmembers, including Gil Cedillo, Paul Koretz, Paul Krekorian, Mitch O’Farrell, Curren Price, and David Ryu. The situation is changing some, given the recent elections of a handful of candidates who campaigned on pro-livability platforms - prominently Nithya Raman and Kevin de León.

The plan will be discussed at today's 3 p.m. meeting of the L.A. City Council's Transportation Committee meeting. Meeting details, including how to offer public comment, are available on the meeting agenda. The meeting was canceled near its start time.

The 47-page plan document is organized into five pillars: Our People, Equity, Health and Safety, Sustainability, and Economic Growth.

In his introductory statement, Mayor Garcetti calls the plan "an honest, assertive strategy that reflects my priorities for LADOT as your mayor." While there are laudable goals in the plan, it is anything but "assertive," except perhaps assertively reiterating that there will be little change to L.A. streets' status quo. Overall the plan does feel very Garcetti: proclaim lots of great high-minded much-needed goals (Vision Zero, more bikes, more CicLAvias), set some far-off benchmarks, then deliver very little, and avoid courting even minimal confrontation - especially with drivers.

The most dismal portion of the document is in the Health and Safety section, which includes active transportation - walking and bicycling. LADOT states that its goal is to "increase the share of people walking and biking to support healthy communities." This is the action with which LADOT plans to accomplish this:

Complete one major active transportation project (such as a protected bike lane on a major street) per year to support the build out of a comprehensive network of active transportation corridors in the city.

Really. One major project each year. That's by a department with a $500+million budget, in a city with four million people, more than 6,000 miles of streets, and an approved plan for hundreds of miles of new bikeways by 2035. One major project per year, which might be a protected bike lane... who knows for what distance.

There's a similar "one project" clause in the Equity section, which describes another worthwhile goal: "Train and empower staff to embed equity in LADOT projects." Then it goes on to drop that plural in "projects":

Collaborate with non-transportation partners to help pilot innovative solutions to broader community issues and deliver at least one coordinated project.

Compared to those single-project goals, LADOT's bus lane commitment sounds 100 percent better:

Partner with Metro to identify and install at least two new bus-only lanes per year.

LADOT and Metro deserve praise for recent bus-only lane installations. During the current fiscal year, LADOT has already implemented three bus lane projects (5th, 6th, Aliso) and has three more (Hope, Grand, Alvarado) anticipated this spring. So the plan's commitment to only two of these projects per year feels like putting the brakes on a successful initiative. The Mobility Plan is full of approved bus lane corridors that won't happen by 2035 if LADOT only commits to two per year. And the bus lane projects are cheap, and already largely paid-for by Metro - and can be implemented quickly, judging from the experience of other cities like Seattle and Boston.

LADOT's Strategic Plan is peppered with non-committal tasks where the department plans to get ready to do things, instead of do things. Examples include:

- "Assess training needs [of LADOT staff],"

- "Develop an index of metrics to measure LADOT’s progress at meeting 'Universal Basic Mobility' commitments across all neighborhoods and identify priority communities for investment,"

- "Establish desired equity outcomes,"

- "Evaluate current transportation-related enforcement practices and research alternatives,"

- "Evaluate the potential to allow [vending in plazas and parklets],"

- "Develop and adopt a prioritized list [of neighborhood streets to calm]," and

- "Evaluate LADOT-owned properties for [potential partnerships]."

These are examples of "actions" that don't specify later implementation steps.

Where implementation steps are specified, many are pretty tepid, including actions such as establishing guidelines, processes, and/or committees - not necessarily implementing on-the-ground changes. Examples include:

- "Establish a community action board... to co-design community-first programs, grant applications, projects, and services,"

- "Create an infrastructure design guide that reflects the ways women, girls, and gender minorities travel... Implement gender-inclusive design guidelines within their jurisdictions."

These are good, worthwhile, needed - but the city already has plenty of official advisory bodies (including pedestrian and bicyclist advisory committees, and Vision Zero committees) and design guidelines (in the Mobility Plan), and LADOT still belches forth unsafe car-centric streets. Maybe one more advisory board will tip the scales and LADOT will finally start paying attention? Don't count on it.

More worthwhile goals paired with minimum implementation show up in this section on Vision Zero:

- Continue to deliver high impact safety treatments on the High Injury Network (HIN), including an annual multimillion dollar signal program and significant roadway improvements to priority corridors

The disappointing key word here is, arguably, "continue." The city never actually got around to funding and implementing those "high impact safety treatments" and "significant roadway improvements," largely due to resistance from city council and backlash from drivers. The plan appears to signal that the city's weak steps toward Vision Zero will continue to be weak.

The new plan calls for more CicLAvia events:

Increase the frequency of open streets events to monthly by 2022 and to weekly by 2023.

This sounds depressingly familiar. Garcetti's Sustainability pLAn called for more CicLAvias back in 2015. LADOT's 2014 Strategic Plan had monthly CicLAvias in 2017. In 2020 Garcetti pledged to make CicLAvia weekly by 2022. Why keep pushing back the goalposts for what is probably the most popular event in the history of Los Angeles? What's the hold-up?

Speaking of earlier LADOT Strategic Plans, there were two prior iterations under Reynolds: 2014 and 2018. The first plan felt downright visionary (especially in comparison to John Fisher's cars über alles LADOT that preceded Reynolds), but then it was watered down in 2018. Now it is being watered down further.

Take a look at these aims spelled out in LADOT's 2018-2020 Strategic Plan:

- "Institute a program for 'slow zones' in targeted areas" including creating "3-5 reduced speed zones per year."

- "Develop outreach and implementation strategy for expanding the bicycle network in line with the Mobility Plan 2035 Bicycle Enhanced Network (BEN)."

- "Consider bicycle facilities in the design and implementation of all street projects."

- "Continue to expand the quality and connectivity of the bicycle network consistent with the adopted implementation strategy and the Mobility Plan 2035 Bicycle Enhanced Network."

- "Build out L.A. River path by 2020."

Sure, the LADOT didn't complete all of those... er... any of those (maybe they did "consider" bike facilities for projects, but just decided against them nearly all of the time), but at least there was some ambition toward making streets safer and healthier.

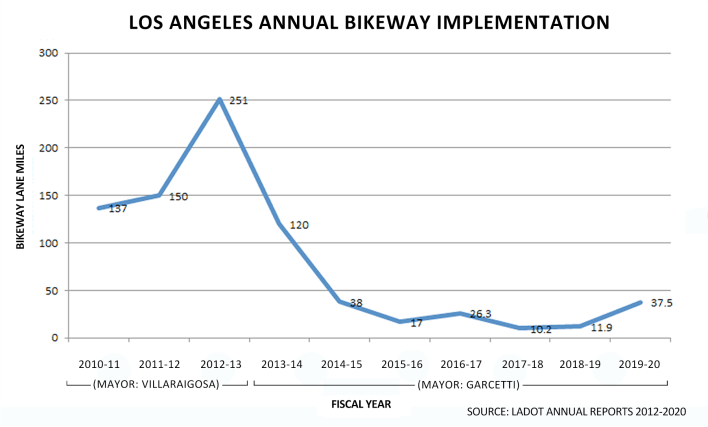

During the years of these Strategic Plans, traffic fatalities (especially pedestrians) continued to grow, and the city's annual new bikeway mileage plummeted.

Overall it now feels like LADOT's Strategic Plan has been dumbed down so much that it's nearly meaningless.

Sure there are worthwhile goals, and the plan commits to at least four projects each year. But the plan is much less aspirational than earlier iterations. And, if the pattern holds, the latest tepid goals are likely to continue being obstructed by councilmembers, resulting in worse - more deadly, less equitable, less green - conditions on L.A.'s mean streets.