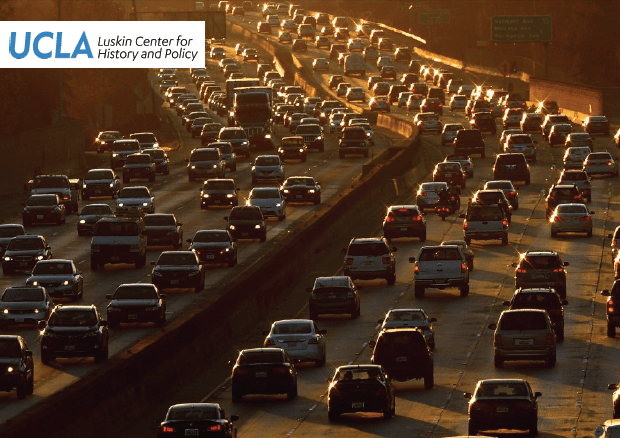

Los Angeles, and California as a whole, has been fighting traffic congestion, and fighting over how to fight congestion, for its entire history. Policymakers are studying potential solutions such as pricing roads - both Metro and SCAG are looking into testing versions of it - but none of the current ideas are new, according to the authors of a new paper, "A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles: 1920-2020." "Century" was published the UCLA Luskin Center and authored by Martin Wachs, Peter Sebastian Chesney, and Yu Hong Wang.

The paper describes century-long arguments over what form the city should take: one focused on downtown? or one distributed into suburban neighborhoods? Arguments for both were based, in part, on trying to solve the growing congestion that was choking downtown streets early last century.

But the arguments were never resolved, just as L.A.'s congestion has continued to grow even as the city expanded. Today, the city is a sort of hybrid, with multiple city centers spread throughout the region. And the many solutions proposed for solving traffic congestion - public transit, encouraging people to move out to suburbs, building ever wider freeways, inventing traffic management regulations and technological fixes - have never brought more than a temporary reprieve from the unrelenting growth in congestion.

The pandemic may have revealed one temporary, very unsustainable solution, but with recovery there is no reason to believe traffic congestion won't come roaring back. That makes right now a good time to take a moment to read up about the history of Los Angeles' long fight to create a transportation system that works, to look at solutions that have been tried, and to learn about what has not worked.

"Proposals to manage traffic in Los Angeles must respond to the land use and transportation landscape that resulted from past programs that we hardly remember," the authors remind readers. Today's proposals are not different from past solutions, and even though mistakes have been made, it's not clear that lessons have been learned.

The debates will continue, and they are likely to be acrimonious, say the authors. But they remain hopeful that there are solutions. "This paper reflects the expectation that the debate will benefit from consideration of new strategies and will be more reasoned if informed by lessons learned from history. The current debate imagines the city of today, with current congestion levels, as a starting point that is difficult to change, but it is better understood as the result of many historical events and policies and ultimately amenable to change."

One post on Streetsblog, highlighting a few excerpts, cannot do justice to "A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles: 1920-2020." The paper gives an overview of everything from the city's complicated history with public transit to the development of technological fixes to proposals for congestion pricing, a strategy that until relatively recently would have been difficult to test.

The paper can be read here in its entirety here. It's worth it - this is a well-written and enlightening dive into these topics. All quotes below are taken directly from it.

In addition to a fascinating look at Los Angeles history, the paper offers some surprising little nuggets that could serve one well at, say, a cocktail party. Remember parties?

Here's one example: In 1966, Caspar Wienberger - the same man who would go on to serve as U.S. Secretary of Defense under Ronald Reagan - proposed a state law that would have set minimum speed limits. He believed this would improve safety, because "slow drivers endangered others who got 'backed up behind the lane hog.' "

Here's another: In 1976, the city of Berkeley volunteered to test out the concept of congestion pricing. Before it could get off the ground, Ronald Reagan, who was at the time a radio show host, got a lot of mileage out of making fun of what he called a "zany idea" proposed by "mass transit zealots."

One of the most surprising - or maybe depressing - lessons to be gleaned is that the many of the proposed congestion solutions have not changed for a hundred years. Today's technology, while it has advanced leaps and bounds past what was available fifty years ago, echoes early tech. Phone apps today provide easy and immediate access to traffic information, but in the 1950s there was the Sigalert, developed in Los Angeles, which allowed police to interrupt radio broadcasts to warn drivers of backups. In 1947, police used a very high-tech approach for the time to clear streets clogged by people leaving the New Year's Day Rose Parade: the police chief, floating in a blimp above the streets, sent radio commands to cops deployed throughout the city "to reroute cars to side streets before police and drivers at ground level could even see the jam of cars backing up several blocks ahead."

Los Angeles Traffic Problems Are Hopelessly Intertwined

Los Angeles has always struggled with congestion. Its population grew rapidly at the same time that cars became widely available, and the city's early suburbs, which were well served by transit, attracted car owners. Growing car traffic slowed the transit that many relied on.

"Slow traffic scared officials in greater Los Angeles regularly for a century," write the authors. "They seemed to think congestion might stop the city's proverbial heart. They were anxious that economic growth might cease and visitors might not return to the city, recalling an awful experience."

Early transit systems were meant as a way to allow people to move to suburbs but stay connected to the center, thus relieving downtown congestion. This was a reflection of those ongoing arguments about whether the city should suburbanize or focus on a dense center, which would keep trip lengths short and make transportation more efficient.

Early regional transit proposals were shot down because suburban areas saw them as a power grab by "downtown interests" seeking to be the central hub of commerce. Proposals for a regional rail system were put forward as early as the 1920s, and again in 1948, 1961, 1974, and 1976. It wasn't until 1980, when the first of several sales tax measures finally passed, that regional transit became a real possibility - and the measure passed in part because it included money for street repair.

Transit was not the only thing planners tried, of course. "Authorities often revived the same traffic reduction tactics, from land use zoning in both the 1920s and 1960s and laws to modify driver behavior in the 1920s and 1980s."

The complex history of trying to regulate driving included street design, traffic regulations, creation and enforcement of jaywalking laws, and parking bans (in 1920 the city tried to ban parking in downtown because it slowed traffic, but "a caravan of drivers came downtown and blocked the streets" and the ban was quickly rescinded). A 1976 experiment on the Santa Monica freeway showed definitively that a carpool lane could reduce congestion and encourage carpooling and transit use, but local media complained that drivers were slowed down, resulting in "a heated public outcry . . . which has delayed the implementation of other preferential treatment projects in Southern California."

There were successes. Specifically, during the 1984 Olympics a wide range of systems management and demand management strategies were deployed to cut traffic - and clear the smoggy air - for the two weeks of the games. It worked. Workers changed shifts, commuters stayed home, and air quality was pristine - and drivers noticed, returning to the empty freeways before the Olympics were over. The same thing happened in 2011 and 2012, when warnings about "Carmageddon" caused by construction kept drivers away from the 405 freeway, and others noticed and came driving back before the projects were scheduled to be finished.

They Always Knew About Induced Demand

"Officials sincerely informed the people they served that each innovation would fix the city's traffic congestion, but history shows that traffic flows grew each time they expanded the transportation system." This is because "traffic is complex and it confounded every effort to reduce it. Where improvements made traffic flow more smoothly, people adjusted the times, places, and modes by which they traveled, and congestion returned."

As early as 1920, and regularly since then, planners have warned that adding more capacity to roads to decrease congestion would ultimately encourage more traffic.

Nevertheless "local leaders since the 1920s have seen congestion not as an excess of cars but as a scarcity of street space, to be remedied by the supply of street capacity." Studies concluded that "Los Angeles had severe congestion primarily because it had an inadequate street system." The argument went that "widening and extending streets would help automobile and transit commuters alike . . . since both modes shared the streets."

"The solution to the problem, if framed this way, seems clear. To fix a street too often jammed with cars we widen it, build another street or road parallel to it, impose new rules to enforce efficient traffic flow, or to tell drivers when and where to avoid congestion."

"Between the 1930s and the 1980s freeways greatly multiplied the region’s capacity to move cars and trucks. They relocated and disrupted the lives of hundreds of thousands of families, eliminated entire communities, concentrated motor vehicle emissions in other mostly minority communities, but were deemed 'necessary' because of the congestion relief provided by more roadway space, grade separation, and limited on and off ramps."

The region built freeways especially where congestion was growing - notably in the San Fernando Valley and Downey, where even today freeways are being widened. This was despite what a 1943 report, "Freeways for the Region," made clear. "The plan did not claim to bring an end to congestion. It acknowledged the limitations of freeways, predicting that even these routes would eventually become congested. 'One can even imagine cars ‘backing up’ on the freeway itself and interrupting the constant flow of traffic,'" wrote the authors of that report, seeming somewhat dubious.

Fuel tax revenue began to be used to fund the building of rural roads and urban freeways in 1947. "More driving increased fuel purchases, which in turn funded more road construction that enabled more driving. This model for funding and administering roadwork later served as a template for the 1956 federal legislation, which funded the U.S. Interstate Highway System."

"In exchange for accepting federal and state money, metropolitan leadership agreed to accept state and federal design standards. Reflective of rural highways, required designs implemented by state engineers rather than local officials prioritized traffic efficiency, driver safety, speed, and saving money on land purchases. Many Los Angeles freeways cut wide and straight or gently curving paths through a number of the city’s lowest-income areas."

The 1970s saw the beginning of "freeway revolts" as neighborhood groups began organizing to fight freeways through their communities. "In less than a quarter century - the time it takes to design a freeway, acquire property, clear its path, and build it - perceptions of freeways had evolved from the belief that they provided needed capacity to satisfy travel demand to condemning them as intrusions creating the traffic themselves."

Congestion Pricing Has Been Studied for a Century

According to the paper's authors, dynamic road pricing was suggested as a way of diverting traffic from crowded roads a hundred years ago. Later, economists argued that road pricing would bring a measure of fairness, pointing out that "negative externalities" of driving - bad air, delay, things that drivers did not pay for - were leading to the “gross underpricing of some modes relative to others.” Pricing, said others, could persuade drivers to make less selfish decisions about where and when to drive.

Congestion pricing "has often been proposed but never adopted in Los Angeles. The technology to enable an efficient system of road charges did not exist . . . . Theorists developed models in anticipation of a time when vehicles would incorporate necessary communications capacities." That technology is now here, and commonly available.

One of the first applications of congestion pricing was on the 91 Express Lanes. Arguments for and against these lanes spanned the political spectrum, with the notion of private companies building and operating toll lanes appealing to conservatives. Meanwhile, they were denounced as "Lexus Lanes" by Senator Tom Hayden, whose politics were decidedly on the progressive/radical end of the spectrum. He claimed that they were unfair to people who couldn't afford them.

But a UCLA study found that, had those four new lanes been built without tolls and financed instead by transportation sales taxes, "the burden of paying for them would have fallen more heavily on low income people. The tolls that financed the new lanes were being paid to a far greater extent by upper income rather than lower income travelers."

Several studies of congestion pricing "have shown that congestion pricing in fact tends to advance the well-being of lower-income and non-white communities. The perception that congestion pricing would harm the poor and non-white residents is intuitive, but not empirically supported, and works to promote the interests of upper income drivers who would have to pay dramatically more under congestion pricing than would the poor."

The city's complex history of grappling with its development and transportation also contribute to "conflicting views of fairness and equity" that are coming into sharp focus under pandemic conditions and in the face of Black Lives Matter protests. But, write the authors, "past and current mobility options in Los Angeles are not obviously more fair or equitable."

The current transportation system, in fact, "is highly inequitable. Travelers having lower incomes, including many Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, depend more on slower public transit, are more likely to live in neighborhoods polluted by vehicle emissions and noise, and pay more in taxes relative to their income to support transportation in Los Angeles than do higher income people."

"Policies like congestion pricing have the potential to rebalance the scales and give drivers incentives to consider carpooling, telework, public transit, bicycling, or living within walking distance to work and shops. In the meantime, congestion pricing along streets with bus lines and bicycling lanes promises more reliable scheduling to the transportation system's most vulnerable population: people without the capital or the ability to drive at all.... Transit-dependent people have far lower incomes than typical drivers in Los Angeles, yet we expect public transit to charge fares. If peak hour bus trips were not priced, the vehicles might become so crowded that they would not function adequately for those making essential trips to work or school. Technological advances make it possible for the first time in a century to apply similar logic to roads and autos."

More evidence comes from Donald Shoup's extensive work on parking demand and supply, which "shows that society benefits from charging all drivers demand-based variable rates to park, as opposed to collecting the cost of 'free' parking indirectly from 'consumers, investors, workers, residents, and taxpayers.' "

"History demonstrates that dynamic road pricing is worthy of serious consideration because it complements earlier approaches to control traffic. Carefully implemented and informed by experiences long forgotten by many, it can enhance mobility for automobile and transit travelers, lessen the harm done to congested neighborhoods, and charge rich and poor people more fairly for their transportation regardless of their race or ethnicity."

Decision makers must remember that "roads and transit are costly to provide, and we have paid for them indirectly through gasoline taxes and sales taxes while keeping the price to drive nearly zero."

Learn from History

Clearly, while much has been attempted, few dents have been made in Los Angeles traffic congestion. The debate will continue, because congestion will continue to cause delay and difficulties for those stuck in it, and as long as driving remains mostly free and apparently convenient, people are not likely to recognize their role in helping create it.

The authors of "A Century of Fighting Traffic Congestion in Los Angeles: 1920-2020" end on a note of hope that things can change.

"Many stakeholders might benefit from reduced congestion more than they would suffer from driving being priced, though most do not yet recognize that possibility. With reduced automobile traffic along bus routes, transit riders could enjoy more reliable service and quicker trips. Drivers who are paid per trip, per service call, or per delivery, rather than hourly, could benefit economically. Managers who oversee just-in-time delivery operations might not have to account for as many variables. Commuters could have more control over their time, and may be motivated to ride on transit or work from home occasionally. The city could require less space for parked and standing cars and more room for housing, services, businesses, and activities that produce more tax revenue. Neighborhoods, workplaces and schools would benefit from breathing less polluted air. Effective congestion pricing could unlock such benefits, but only after the concept is carefully studied and is accepted by a majority of representatives of many constituencies. Nobody wants to pay for something that is currently free, but we must systematically compare a system that levies congestion prices against free streets and regressive gasoline and sales taxes, parking fees, and valuable lost time."