Three years ago, I got an email asking me to cover the extent to which a homeless person was infringing on the rights of bus riders by taking up residence at a bus shelter. The city had posted notice it was going to do a clean-up there, the sender said, but the deadline had passed and he was beginning to lose patience.

I pushed back, suggesting the gentleman consider deeper structural issues and the extent to which folks were being squeezed out of areas like downtown, thanks to rapid gentrification there. Through the course of research for other stories I had been working on around that time, I said, I had also been told that sometimes delays in clean-ups were a product of various agencies struggling to find someone services so they weren't just pushing that person from corner to corner.

He wanted to hear none of that, arguing that respecting the rights of a "homeless dude" harmed the "greater good" and telling me he looked forward to me writing a story uplifting that viewpoint.

Reader, I did not write that story.

But many others have in recent years.

And this past week, we had a few doozies.

Steve Lopez of the L.A. Times looked very vulnerable people in the eye, acknowledged that most of them had probably experienced significant - including sexual - trauma as children, and then turned to camera and asked, "How many more of these poor schmoes must we be on the hook for?"

The fact that so many of those seeking a safe haven in Hollywood are LGBTQ+ youth - including a disproportionately high percentage of youth of color - who have been rejected, abused, and failed by social safety nets at every turn, made the labeling of "them" a burden on "us" all the more cruel.

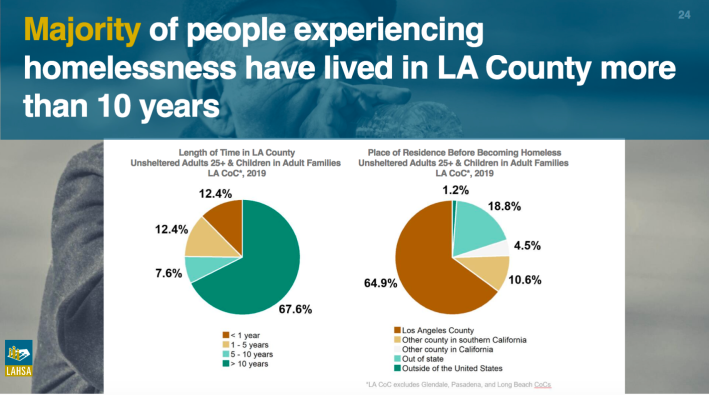

So did his framing, which fed the myth that the majority of our homeless residents come from elsewhere. [While the Hollywood population is unusual in that it does tend to originate from a range of places, a quick check of the data from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority's most recent count would have confirmed that, with regard to the total population in L.A., not only is the opposite true, the majority of folks have been here for a decade or more.]

"Hold my dehumanizing beer," said NBC Los Angeles, which has spent much of the last year painting the unsheltered as dangerous and/or mentally ill criminals for their Streets of Shame series.

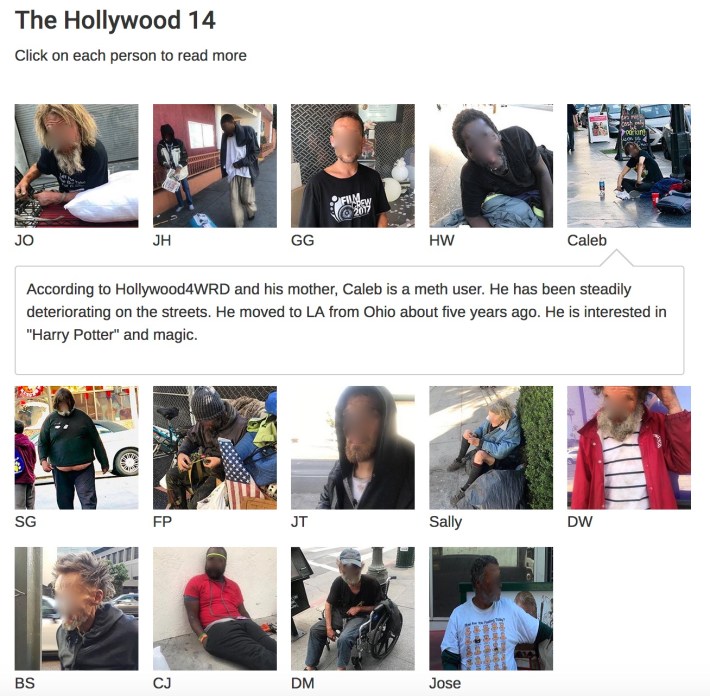

Their report, posted the same day as Lopez' story, featured the equivalent of a wanted poster for "The Hollywood 14" - a list created by Hollywood 4WRD a few years ago to identify the area's most vulnerable members of the chronically homeless community.

Viewers were invited to click on a photo to learn more about the addiction status and/or medical case history of those pictured below. No mention was made of whether those pictured consented to having their personal information being broadcast this way. [Their faces have been blurred by me.]

The report went on to dip its toes into Caleb's story (highlighted above), intercutting images of him incoherent and seemingly oblivious to his surroundings with snippets of others (including his heartbroken mother) opining on his condition and what should be done with him.

He was effectively a backdrop, not a participant.

It's a pattern NBC has perfected for its series - giving more voice to those affected by their encounters with the unhoused than vice versa, despite the fact that attacks on the homeless are on the rise and that they're dying in record numbers on the street.

That approach has made for some troubling coverage choices on NBC's part, including the validation of right winger Scott Presler, all because he came to L.A. to clean up a blighted encampment this past September.

Presler, who coordinated a national "March Against Sharia" as part of his work with the anti-Muslim group ACT for America in 2017, had done his first clean-up in Baltimore as a way to help shame late congressman Elijah Cummings after Trump attacked Cummings online. Though not specifically billed as a political event, both Trump's attacks and conservatives' subsequent interest in Baltimore were in service of the claim that the right cared more about Black people than Black people did.

Presler has since used footage of his clean-up in L.A. to ask, "Why do illegal aliens come first and homeless Americans come last?"

For NBC, who chose to label Presler only as a do-gooder conservative activist, it appears the threat posed by trash trumps that posed by racist hate groups.

Giving a platform to this kind of punching down legitimizes fearmongering.

And it helps punitive solutions overshadow consideration of more substantive and structural ones - something that is profoundly troubling, given that the homeless population is not just disproportionately of color, but disproportionately Black.

One need look no further than the Facebook groups that threaten violence against homeless residents, or recently-elected councilmember John Lee's campaign page, which prioritized policing the homeless, or councilmember Mitch O'Farrell's draconian proposal to restrict sleeping on sidewalks, or even the Times' decision to run the results of a badly designed poll from a business council on their front page with the headline, "Many Support Larger Role for the Police" [or online, "Majority Says Police Should Do More to Clean L.A. Streets Clogged with Homeless Camps, Times Poll Finds"] to see why that might be of concern.

Giving those narratives so much real estate also suggests that we, as a city, care much less about the issue itself and instead long for the days that folks were more contained on Skid Row.

Because as recently as 2005, there were 90,000 homeless people in the county - 30,000 more than are on our streets now. It just was less visible.

When it did become more visible - as downtown hemorrhaged affordable units along the edge of Skid Row and the well-heeled suddenly found themselves sharing space with those residents - the city made a choice about whose rights it would uphold.

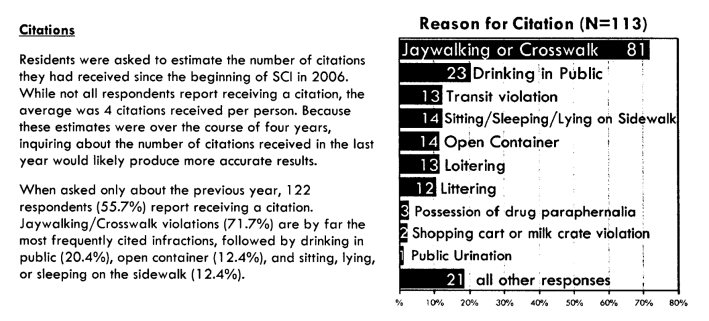

The Safer Cities Initiative (SCI), launched in 2006, was billed as a two-pronged program offering both "enforcement" ("Broken Windows"-style policing of minor infractions) and "enhancement" (more shelters, drug treatment, and services).

The latter never materialized.

Instead, Skid Row residents were regularly cited or arrested for things like jaywalking and sitting on the sidewalk, according to an evaluation of the program by UCLA professors Gary Blasi and Forrest Stuart. Meanwhile, the city failed to follow through on the basics, like installing eleven trash cans - something which might have helped folks avoid littering citations and any of the related consequences (e.g. fees, losing access to services) that helped keep them underwater.

The association of Skid Row residents with criminal behavior ensured there would be few places where they were welcome, even as they were being displaced from downtown.

Just one year later, in 2007, the county found itself forced to shelve a $100 million plan to build five regional "stabilization" shelters for the homeless because the targeted communities feared they would draw people away from Skid Row.

Little has changed in the intervening years. The mere mention of a shelter being put up in a community is enough to see the housed start digging through their walk-in closets to find their pitchforks.

Coverage that takes swings at the city's most defenseless residents does not help in that regard.

And yes, they are residents.

Seventy-five percent of the unsheltered have lived in L.A. County longer than five years. Sixty-eight percent have lived here a decade or more. As residents, and as humans, they deserve better than business council surveys asking homeowners about whether the unhoused have too many rights.

Because while such a survey might capture the frustration we all - the homeless included - feel about the unhealthy state of our streets, it doesn't move us any closer to a solution.

It just gives agencies and elected officials cover to push vulnerable folks around.