Last week the Los Angeles City Council unanimously approved an important change to the way transportation impacts are measured. If that first sentence didn't put readers to sleep, the sheer weight of acronyms likely will: LOS, VMT, CEQA, and more. Nonetheless, this is very important progress likely to have big ramifications for making L.A. healthier, more walkable, more bikeable, and transit-friendly.

One place to begin the story is the state legislature in 2013. Legislators and the governor approved S.B. 743, which directed California to, over time, abandon Level of Service (LOS) as a tool in the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA.) Environmental studies are done on all kinds of big projects, from housing developments to highway widening. CEQA ensures that the public has some say in the project planning processes.

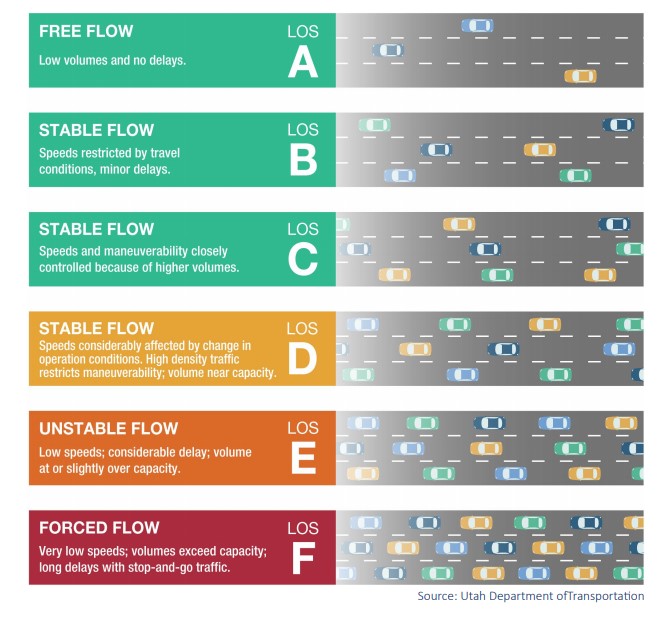

LOS is a way of measuring traffic, though it perniciously and simplistically only measures car traffic, and doesn't even do that meaningfully. Measuring for LOS shows any project that increases car congestion - such as building new housing - as adversely impacting the environment. To supposedly fix congestion - the adverse environmental impact of that new housing - LOS measurements end up requiring more space for cars, so a housing project might also have to widen the road. LOS incorrectly assumes that car traffic is a static quantity, denying the effects of induced travel. LOS said that the 405 Freeway would be less congested after it was widened. That didn't happen.

LOS wasn't originally part of CEQA when it was passed in 1970. Over time, courts tied LOS to CEQA, which meant that California environmental analysis yielded pro-car results. LOS shows that widening freeways is good for the environment, while bikeways and bus lanes, where they take space from cars, are bad for the environment.

In 2013, the state legislature was grappling with how to respond to climate change. S.B. 743 mandated that the state's environmental review processes align with actual environmental goals. CEQA analysis needed to support reducing greenhouse gas emissions, not increasing them, which is what LOS does.

In 2014, California's Office of Planning and Research began evaluating what metric could replace LOS. Over time, and after a lot of feedback and discussion, they settled on Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT.)

Measuring environmental impacts under VMT more accurately shows that projects in denser urban areas have less adverse environmental impacts than projects in less dense suburban areas. New housing next to a rail station generates fewer new car miles traveled than does housing in a far-flung suburb. Urbanize describes it well: "Rather than treating traffic congestion faced by drivers as an environmental impact, this new metric instead considers the act of driving itself as the environmental impact."

In January, California adopted the final CEQA rules that replace LOS with VMT statewide. Those new rules go into full effect statewide on July 1, 2020. There is a loophole that says LOS can still be used on road capacity expansion projects, but overall LOS is no longer the method California will use to measure environmental impacts.

CEQA is state law, but is triggered based on thresholds set at the local level by municipalities. That is, cities decide the threshold at which added VMT from a project would require some kind of environmental mitigation. All California cities are required to set their local VMT thresholds by July 1, 2020.

Last week, Los Angeles joined a growing number of California cities - starting with Pasadena - that already shifted to VMT.

L.A.'s City Planning (LADCP) and Transportation (LADOT) Departments created new customized CEQA VMT thresholds, which were adopted last week. The thresholds are based on local travel demand, recognizing that projects in more walkable parts of the city generate fewer car trips than more car-oriented areas.

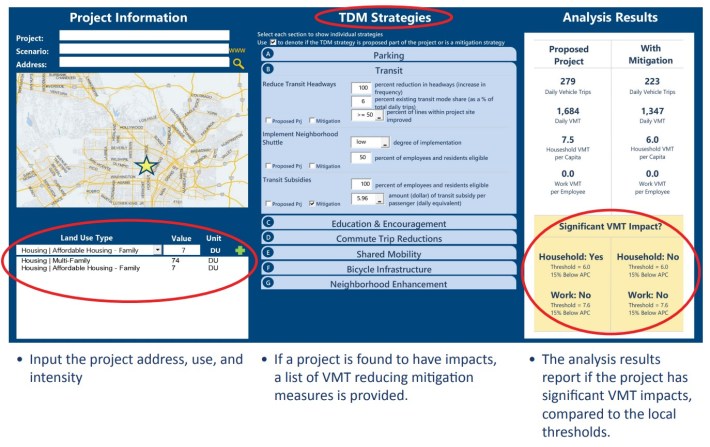

L.A. created an online VMT calculator, so a developer can enter what type of project they are planning and determine how much VMT it would generate. If the VMT is above the city's thresholds, the developer needs to mitigate the environmental impacts.

Instead of LOS car-oriented mitigation, VMT mitigation is based on TDM, or transportation demand management, principles - strategies that can help reduce driving. In the city's calculator these include: reduced parking, unbundled parking (paid for as a separate expense from rent, for example), transit subsidies, vanpools and rideshare programs, car-share, bike-share, bike facilities, traffic-calming, and walkability improvements.

The Natural Resources Defense Council's Carter Rubin praises L.A.'s VMT calculator for increasing transparency and reducing the time and effort put into "convoluted congestion management modeling" under LOS. Developers and the community can use the calculator to see what sort of traffic a development would generate, and what can be done to reduce adverse impacts.

LADOT spokesperson Nora Frost reports that L.A.'s new VMT rules are now in effect, though "proposals that are already in the pipeline and have already initiated LOS-based analyses will be allowed to proceed. However, if these projects have significant impacts, we will prioritize TDM measures to mitigate. These projects in the pipeline will be allowed to substitute their LOS analysis with a VMT analysis."

The effects will not be felt immediately, but the new VMT approach is a truly important shift. Los Angeles' and California's environmental planning processes are now better rooted in actual impacts to the environment. VMT puts the E back into CEQA. Over time, VMT helps communities become healthier, more walkable, more transit-oriented, and more sustainable.