“We believe that the next battleground is cities.”

Zena Howard, principal architect with Perkins+Will, was explaining why both she and the firm had gradually been shifting their focus from a museum typology to projects like Destination Crenshaw, where the task was to create space for Black people and African American culture in urban environments.

Heads bobbed in agreement.

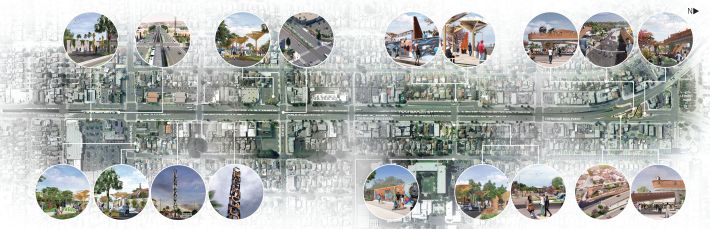

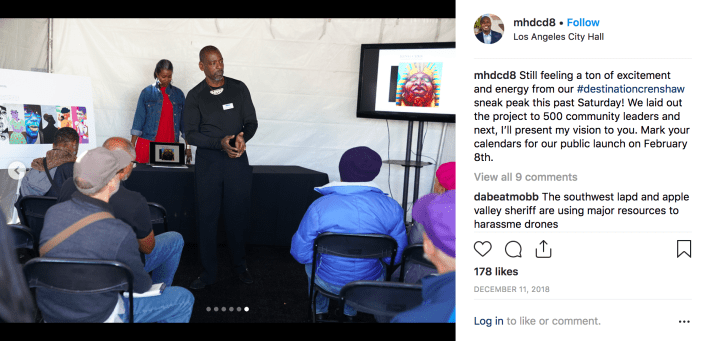

As far as the stakeholders gathered at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza (BHCP) last December 8 to get a preview of the 1.3-mile-long open-air “People’s Museum” honoring Black stories, culture, and contributions were concerned, she was preaching to the choir.

Many of the same places that are now more open to acknowledging their Black populations also spent decades working to undermine and disperse those same populations. Black communities were razed to the ground in the name of “health” and “renewal.” Major infrastructure was run through the center of thriving Black commercial corridors. Even the wealthiest were not immune - Los Angeles deliberately routed the Santa Monica Freeway through Sugar Hill, once home to Oscar-winning actress Hattie McDaniel (below).

![The wealthy Black community of Sugar Hill [the angled streets seen here between Western and Normandie Avenues] was one of several Black neighborhoods officials deliberately routed the Santa Monica Freeway through in the 1950s. (Google maps)](https://lede-admin.la.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2019/01/sugar-hill-graphic.jpg?w=630)

In later years, disinvestment, mass incarceration, repressive policing, disenfranchisement, and the denial of access to the subsidies that facilitated white flight would help reinforce the barriers to mobility - physical and otherwise - that tangible infrastructure had imposed.

More recently, the reversal of flight patterns has ushered in a new wave of threats. These rely less on physical displacement and more on erasure and the whitewashing of communities to make them “welcoming” to and “safe” for whiter, wealthier newcomers. Although the attempted rebranding of neighborhoods is driven more by private investment via revamped residences, eateries, and establishments, cities eager to market themselves as more livable have institutionalized "place-making," prioritized the “reimagining” of key corridors, and sanctioned the renaming of communities (“SoLA,” anyone?) in ways that appeal to “pioneers” looking to “discover” the next “up-and-coming” neighborhood. Whether publicly or privately driven, however, the underlying assumption remains the same, namely: there is nothing and no one of value in the existing community.

Cities have never not been battlegrounds.

An observer would be hard-pressed to find a time in L.A.'s history in which people of color and their claims to place weren’t actively being subjugated, contained, repressed, displaced, erased, or "re-imagined."

Crenshaw just happens to be one of the more visible front lines.

Turning Insult into Opportunity

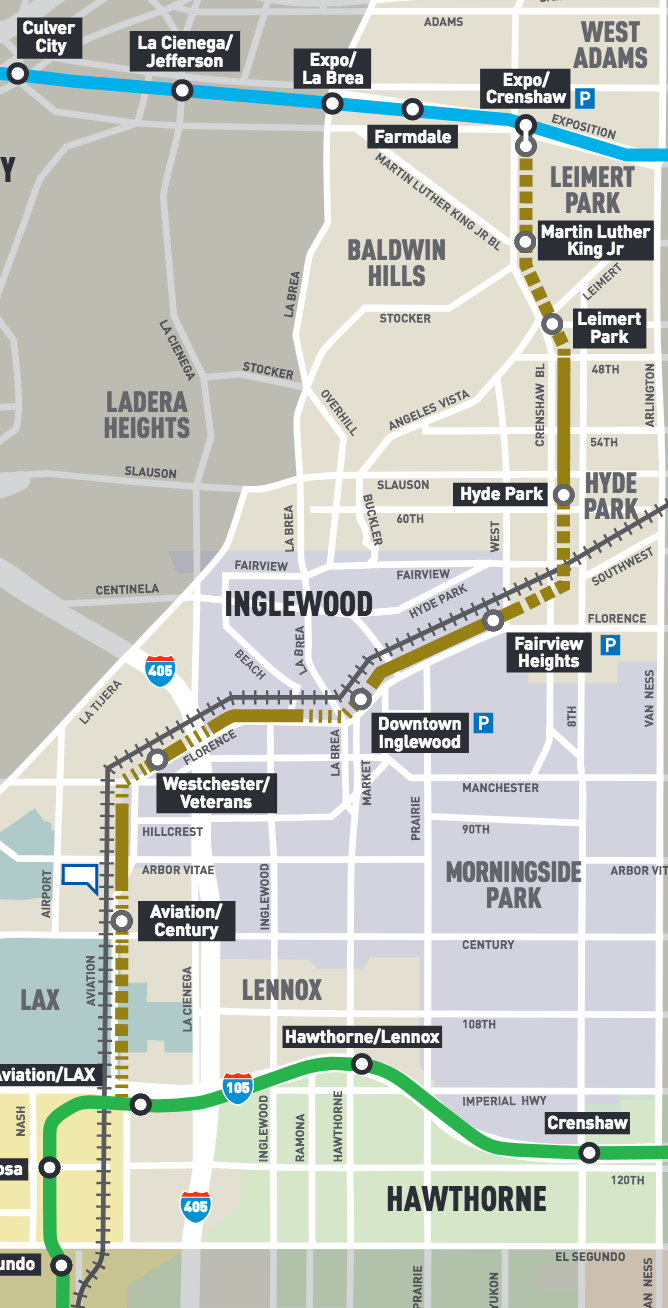

When, nearly a decade ago, Metro laid out its plans to save on construction costs by running the Crenshaw/LAX Line at-grade up the spine of the Black community, many had feared it could jeopardize the survival of the last remaining Black-owned business corridor in the city.

The fact Metro had originally planned to bypass Leimert Park Village - the “cultural beating heart” of the Black community - added to the sense that Metro fell somewhere between being indifferent to the community’s value and being openly hostile to it. At the very least, community members argued at the time, Metro would never have contemplated bypassing other cultural markers, regardless of the costs. [The community would eventually prevail - there will now be a Leimert Park station at 43rd Place and Crenshaw when the train finally arrives in 2020.]

More recently, Metro has tried to demonstrate a commitment to working with the Black community and to mitigating the harm caused by construction via a business interruption fund, efforts to hire local, and its "Eat, Shop, Play Crenshaw" promotions. It has also sought to make transportation investments bounce in the community by supporting the County’s effort to reclaim the blighted lots at Vermont/Manchester and approving plans for a specialized boarding school intended to help establish a transit careers pipeline in the community.

Yet continued stumbles, like the failure to anticipate the damage inflicted by images that whitewash the community or paint Metro’s Black and brown ridership as undesirable, suggest that deeper issues remain embedded within the agency. And the extent to which the Metro-funded art planned for the stations along the corridor largely avoids engaging or even acknowledging the Black community’s claim to place signals Metro is not yet ready to reckon with the role public investment and infrastructure have played in reshaping non-white communities.

The pending arrival of the train has made it all the more urgent for the community to take visible ownership of the public space along Crenshaw. Not just to push back against threats of erasure along the corridor, but also to secure the larger place of the Black community in Los Angeles, both real and imaginary.

We-built-this-place-making is no minor undertaking, however.

For one, "this is not something they ask you to do…or invite you in the room [for],” Eighth District Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson had told stakeholders gathered at the Museum of African American Art (MAAA) for Destination Crenshaw's first public unveiling back in March of last year. “This is something we have to assert [ourselves]."

Leimert Park Village stakeholders had been reminded just how difficult that process could be when they launched their 20/20 Vision Initiative in early 2014.

Much like with Destination Crenshaw, the goal was essentially to "hack" the arrival of the train - to cement the identity of the area as a hub for Black creatives and the celebration of the diaspora - and effectively harness any change it would bring. And much like with Destination Crenshaw, creating the infrastructure for an inclusive community-driven effort required more than just weekly meetings and regular community-wide planning charrettes. Behind the scenes, relentless advocacy on the part of key drivers maintained the initiative's momentum over time while ongoing conversations around shared goals deepened its reach over the long haul.

But even when the Leimert Park stakeholders were "invited in the room" in 2014 (after putting together a winning proposal for the transformation of 43rd Place into a pedestrian plaza), it was largely on the city's terms.

The stakeholders would ultimately spend a year and a half wrestling with the city over how to make a cookie-cutter template more reflective of the community's identity. Even at the ribbon cutting (above), city staff continued to frame the plaza project as an end - a successful reclamation of physical space from cars for people - while stakeholders touted it as yet another means to anchor their long-running effort to carve out space for culture and community.

The adjacent Crenshaw corridor presents a much larger canvas, a much broader swath of stakeholders, and a much higher set of stakes.

The elevated stakes are also why the community couldn't ignore this chance to "turn insult into opportunity," as Harris-Dawson has often described the impetus for Destination Crenshaw.

Leaving the corridor to serve as a backdrop people moved past on their way to more established monuments to L.A.'s cultural life was not an option. The community already knew what that looked like. They'd seen it as recently as 2012, when the Space Shuttle Endeavour was routed through the heart of the district, leaving torn-up streets and the removal of hundreds of trees in its wake.

Instead, it was time for what Harris-Dawson has called the "capital of Black life” to be appreciated on its own terms.

The path forward was therefore clear.

Concluding his pitch to the stakeholders gathered at MAAA, he declared, "We say to the world, 'If you’re going to run a train at-grade through our neighborhood, nobody's going to be able to get through without seeing and hearing and feeling and sharing our story!'"

A Vision Comes into Focus

It is one thing to take inspiration from Harlem - at least, from what Harlem represents - and envision marking a space as for now and forever unapologetically Black.

It is something else entirely to try to narrow down an agreed-upon history or shared set of values and priorities that will effectively honor the community's collective journey.

It is all the more difficult when the devaluation of Black voices means there is no central location where the community's stories are archived and easily accessed. Or when its history is tied less to specific moments and more to the strength and creativity it called upon as it improvised, innovated, and dreamed its own transcendence into being.

So Harris-Dawson did the same thing he had done during the two decades prior to his election to Council in 2015: he began organizing his neighbors.

In informal meetings in the homes of residents and thought leaders, he and his staff listened to stories of how folks had first come to be in the community, what had happened to their families in the intervening years, and how their experiences had shaped their connections to place and to each other.

By the end of 2016, informal conversations had given way to more formal convenings where stakeholders debated overarching narratives and guiding themes. A formal advisory committee comprised of community thought leaders, including artists, curators, storytellers, and experts in planning, culture, and history was named and would meet regularly over the following year to narrow down overarching narratives and guiding themes.

Within months, a team from Perkins+Will, the architecture design firm behind the NMAAHC and the expansion of Detroit's Motown Museum, had signed on and begun translating the themes and narratives the advisory committee had identified into physical form.

![Thought leaders, including Ben Caldwell, James V. Burks, Ron Finley, Adam Ayala, Karen Mack, Larry Earl, and Alberto Retana, gather in early 2017. [Click image to visit original Instagram post]](https://lede-admin.la.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2019/01/dest-cren-advisory-mhd.png?w=710)

Throughout the process, the councilmember's office emphasized face-to-face engagement with stakeholders - block club by block club, neighborhood council meeting by community event.

Even the press was deliberately kept at arm's length. For once, residents would be the first to hear about major changes coming to their streets and see their input shape the form those changes would take. And they would hear it from community leaders in settings that allowed for conversations about the impetus behind the project, who it was meant to serve, and potential impacts, all before ground was ever broken.

The councilmember's office even tapped Grammy-nominated rapper, artist, and entrepreneur Nipsey Hussle (below) to help ensure area youth contributed their visions for the project.

![Nipsey Hussle (at center) and Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson (at right) meet with students to talk Destination Crenshaw and the future of the community. [Click image to visit the original Instagram post]](https://lede-admin.la.streetsblog.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2018/12/Screen-Shot-2018-12-13-at-4.44.29-PM.png?w=710)

Perhaps more significantly, Hussle's inclusion as a thought leader also signaled a unique commitment to uplifting marginalized youth on the part of the councilmember's office.

Often regarded as a source of blight (rather than a product of it), gang-affiliated and other at-risk youth tend to be the first to be pushed aside, hit with gang injunctions, and more intensely profiled when improvements are made to parks and other public spaces.

Narratives about gangs and gang culture have been and continue to be used by those outside the community to criminalize Black youth and paint the larger community in a negative light. And while community members might understand the structural conditions that gave rise to gang culture all too well, many have also lived through the harms it continues to visit upon their children, their neighbors, and their streets. Even Harris-Dawson's own family had left South Central during the peak of the violence when he was a child - a choice he wanted to make sure no other family would ever feel compelled to make.

Although the landscape has changed over the years, any association with gang culture remains fraught.

As such, the participation of Hussle - who came up in the Rollin' 60s - hasn't always been a comfortable fit.

But the combination of his enthusiasm for transforming Crenshaw into a destination and his drive to find ways to lift the neighborhood up with him have helped him defy categorization. Between his flagship Marathon clothing "smart store" (located at the corner where he grew up hustling T-shirts and, famously, his $100 Crenshaw mixtape), thoughtful engagement with gang culture and structural oppression in his music and his work, and unwavering fidelity to the community, he encapsulates much of what Destination Crenshaw aims to showcase.

He is also uniquely positioned to speak to those most likely to feel alienated as things change around them. His participation validates their struggles and opens the door for their stories to be integrated into the larger history of the community in a way rarely seen in public projects.

Making a project on the scale of Destination Crenshaw work is about much more than just getting a diverse range of thought leaders into the same room, however.

Throughout the planning process, Harris-Dawson said, elders had repeatedly reminded him of the weight of what he, his staff, the community partners, and the Perkins+Will team had taken on.

He would essentially have one shot at this project, he was told.

He would therefore have to "do it right, do it in order, and do it at the highest level.”

Race, Space, and Place: A Public Reckoning

The greatness of the burden is something the design team at Perkins+Will is well aware of, according to Howard.

By the time the firm has been invited in to capture a community’s story, she lamented to stakeholders this past December, it is usually too late.

Too many bouts with “root shock” - the trauma and upheaval that comes with displacement and the destruction of one’s emotional ecosystem - have eaten away at too many communities’ capacity to retain their foothold in a place.

“They’re just not there,” she said.

Consequently, the projects Howard works on are often oriented towards illuminating what once was and helping people find their way back.

Crenshaw, she argued, is different.

As a community, it had not only collectively weathered “root shock,” but had managed to remain vibrant, vital, physically present, and continuing to produce culture that was both deeply tied to place and resonant far beyond its own borders.

“This community is here,” Howard said. ”It’s been here for generations. It’s intact. It has not only planted and thrived, it has actually contributed to the broader culture of our country and, I’d say, our world.”

Residents might dispute the extent to which the community is intact.

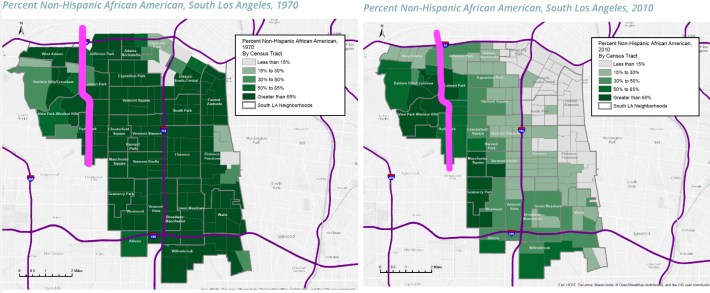

Black folks fleeing the Jim Crow South had boosted the community’s numbers from 75,000 to 650,000 between 1940 and 1960. But it wouldn't be long before the cumulative trauma of deteriorating housing conditions, job losses, continued denial of access to opportunity and services, and police brutality sparked unrest and waves of out-migration.

The recession and the foreclosure crisis also hit South L.A. particularly hard, sending Black unemployment and underemployment to levels rivaling those seen in the lead-up to the 1992 unrest. Between 1970 and 2010, L.A.'s Black population had dropped from 17.9 percent (just over 503,000 people) to 9.6 percent (365,118 people).

Even as the region has recovered, the more vulnerable members of L.A.’s Black community have struggled to regain surer economic footing while the overall population of the community has continued to fall.

It’s why some are fearful of what transforming the corridor into a destination could bring.

After so many years of neglect, the community is indeed desperate for investment and for proper respect to finally be accorded to Black dollars. But should the project make the community more attractive to outsiders, it could accelerate existing speculation along the rail line, further squeezing those businesses and residents already on the margins.

In an interview last July, Harris-Dawson acknowledged investment can be a double-edged sword.

He also made the case that part of the work of helping a community remain in place included the neighborhood first being clearly identifiable as a Black space, like Harlem.

In that vein, Destination Crenshaw would not, on its own, prevent gentrification.

But in calling upon Black voices to communicate the community's significance, Harris-Dawson suggested, it could play a role in the extent to which it remained a place for the celebration of Black people over time.

Moreover, he continued, it would help refocus attention on South Central as an originator of culture.

Whether appearing on Soul Train and shaping dance and fashion trends back in the day, nurturing hip hop talent at the Good Life Café, or dictating tastes in music and fashion now, area youth have always led the way. Yet their contributions continue to be appropriated, stripped of meaning, repackaged, and marketed back to them for someone else to profit from. It's a dynamic that leaves the community vulnerable to erasure long before the last Black residents are physically pushed out.

Destination Crenshaw will, ideally, open the door for the community to better leverage its contributions.

Speaking to the stakeholders gathered at the BHCP about the art planned for the corridor, self-described Gangsta Gardner and project advisory committee member Ron Finley was more blunt in describing the line the project was walking.

"Are we making this for other folks to move in? No."

Instead, the goal is to “lead with culture” and communicate to community members that the project is, first and foremost, for them.

The corridor will not just be a place to celebrate unapologetically Black contributions, but also a place where it is safe to be unapologetically Black in Public: A Black Space, full stop.

"I mean Black for real, for real," Finley said. "Like, skillet Black. Like, blackity-black Black. Like, you-can’t-see-your-hand-in-the-dark Black."

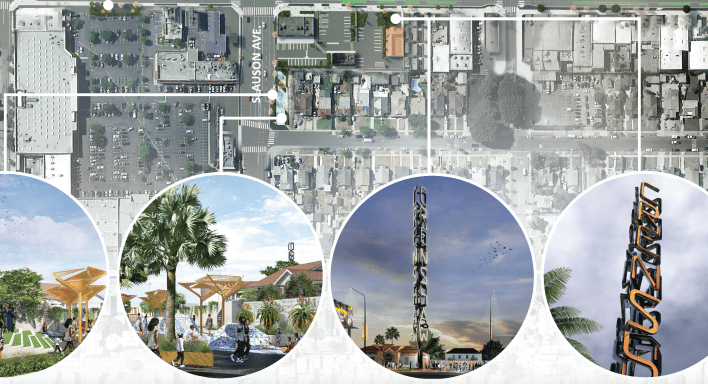

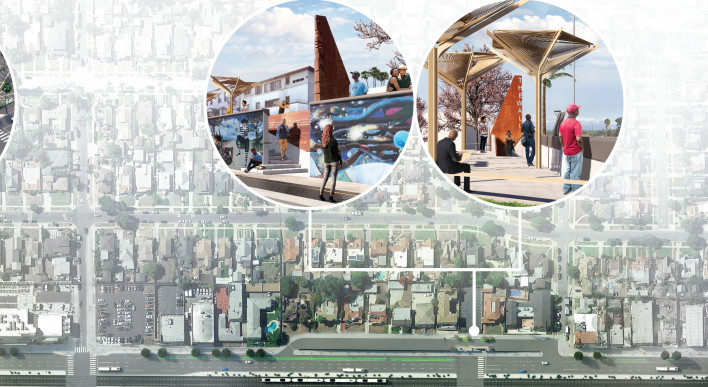

Nearly a dozen permanent artworks installed in the eleven pocket parks planned for the corridor will help anchor that identity in the key themes used to communicate the community’s journey.

So will the 120-foot-tall monument that will tower over the boulevard broadcasting the Crenshaw name from the grounds of the Historic Fire Station near Slauson.

But given that Blackness is ever-evolving, and that “there is not one Black L.A. story,” says Tafarai Bayne, advisory council member and Chief Strategist with CicLAvia, the approximately 100 rotating installations and ongoing performances, celebrations, and workshops will actively engage local artists, activists, and members of the community in dialogue with that identity, pushing it forward.

“A lot of this project is about creating programmable space where the Blackness can be layered on in a contemporary way that represents what Blackness is now. Or tomorrow. Or 100 years from now,” says Bayne. “We’re setting the stage for Black people to take it into the future.”

The project’s openness to that kind of shapeshifting, he says, “honors what Blackness has always been: adaptable to the world; changing; self-determining; and [transcending] the conditions we’ve had to deal with over and over.”

It is also in keeping with the Sankofa - the mythical bird that calls upon lessons from the past to help illuminate the path ahead.

Long a guiding presence in Leimert Park, the Sankofa will get its due in Destination Crenshaw, as well, with its own pocket park and monument granting patrons a vista from which to overlook and contemplate the community’s trajectory.

The fact that carving out deliberate space for Blackness has been such a massive undertaking speaks to the extent to which it has been historically chased out of and denied dominion over the public space. Similarly, the high price tag - project team members cited costs ranging between $70 and $100 million in private funds and the need to establish of a non-profit entity to maintain the project as a living, breathing space over the long haul - hints at the depth of the damage done by the decades of disinvestment and disenfranchisement.

Even cobbling together a project team that truly understood the community's experience was no small feat - Howard, Lead Principal on the project, and L.A.-based Gabriel Bullock, Managing Principal on the project and Perkins+Will's Director of Global Diversity, for example, are two of only just over 400 licensed Black women architects in the entire country.

When considered in the context of the deep-seated resentments the current administration has tapped into, says Bayne, the urgency of such a project becomes clear.

“When Black people are loud, it’s always seen as a threat,” he says. But “when you’re dealing with as difficult battles as [the ones] we’re dealing with, you have to do riskier things."

You have to be even louder.

"By all metrics, it’s life or death for us.”

But Let's Not Talk about Him, Let's Talk about Us

Cause They Won't Change so We Just Must

- J Sumbi/Legal Alien/Freestyle Fellowship

That story of survival, and the resiliency it continues to require, Howard had explained in December, is woven into the overarching theme of the project: Grow Where You Are Planted.

Specifically, it comes in the form of Giant Star Grass, a hearty East African plant used as bedding hay on the Middle Passage.

Despite being uprooted and drafted into providing a service for which it was not intended, said Howard, it had managed to anchor itself in a hostile environment on a new continent and thrive.

Key to the rhizome’s ability to avoid root shock, she continued, was the energy invested in building a strong root system. Once settled somewhere, the roots would expand horizontally, creating new nodes. Those nodes, in turn, would incubate new root networks and send new shoots skyward to have their moment in the sun.

It’s a process that, in many ways, mirrors strategies employed by a community that had no choice but to build its networks “underground.”

The strength, resistance, creativity, and inspiration nurtured in those spaces forged bonds powerful enough to radiate beyond borders and re-establish connections imperial powers had worked so hard to sever.

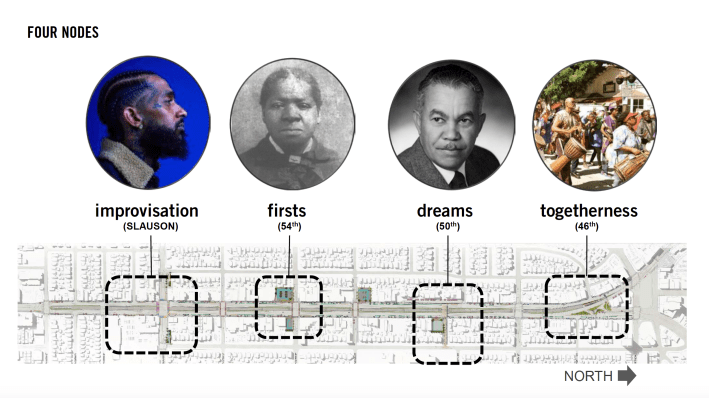

The story of how the community evolved will be revealed more explicitly at each of the thematic nodes.

At Slauson, “Improvisation” will speak to the community’s resourcefulness and capacity to transform adversity into opportunity, with Nipsey Hussle’s own story grounding that conversation in the present. At 54th Street, “Firsts” will trace through-lines from Biddy Mason (who petitioned for her freedom, became one of the first Black women to own land in L.A., and was a founding member of the First AME Church), to the entrepreneurs behind Shinanda Toys (whose creations included the Black Baby Nancy doll), to present-day pioneers, like musicians Kamasi Washington, storytellers Issa Rae, Ava DuVernay, and Kendrick Lamar, and warrior and Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors. At Vernon, “Togetherness” will illuminate the vibrant human infrastructure the Leimert Park Village has carefully cultivated over the years – one that draws on wisdom of the ancestors and leads with unity.

Finally, centered around the 7800-foot-long mural at 50th that was the inspiration for Destination Crenshaw, the “Dreams” node will invite people continue to push beyond boundaries and barriers.

Painted by the Rockin’ the Nation Crew in 2001 to uplift and unify the community, the “Our Mighty Contribution” mural walks observers from the dawn of time (where a Black woman breathes peace into the universe) up through present day, where another Black woman gives birth to the future. As part of the construction of Destination Crenshaw, the Wall will be restored, protected, and lit. A new pocket park will be set above it, offering a unique vantage point on the corridor.

Pocket parks will grace each of the other nodes, as well, creating opportunities for deeper engagement with the specific themes. The parks will also vary in size and function, with some being able to support larger gatherings and others being better suited for play or quiet contemplation.

During their December presentation on the pocket parks, Perkins+Will architects Malcolm Davis and Kenneth Luker described the overall project as a game-changer for the community, for the city, and for embattled communities around the country.

The game-changing potential of the project is something Harris-Dawson and others have also alluded to when talking about the significance of Destination Crenshaw - that both the project and the intentionality behind it could offer a template to other communities pushing back against erasure.

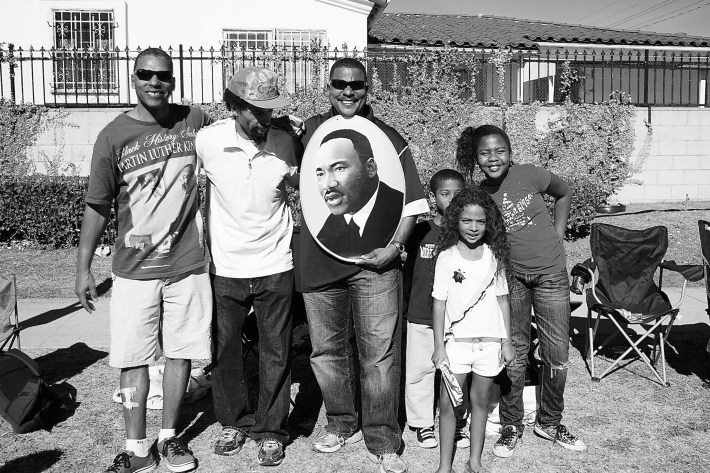

Members of the public taking all of that information in at the King Day festival in Leimert Park this past January 21 (below) seemed to agree with the urgency and mission of the project (even if not all were on board with things like the design of the shade structures). They agreed it was time to see their surroundings reflect their stories, particularly given how quickly everything was changing around them.

For Richard Copes, a resident of the Vermont corridor who had watched the area around Manchester languish for decades, however, it wasn't nearly enough.

His hand shot up at the end of Davis' talk.

"What about Vermont?"

The project looked great, he said, but the youth over there were in desperate need of something like this. That community also deserved to be uplifted.

Which, of course, it does.

It, too, is a battleground, if of a slightly different kind. The extent to which massive vacant lots have held it hostage to blight for nearly thirty years means its erasure is more heavily driven by grinding neglect and oppression than the arrival of newcomers. At least, at present.

Still the question speaks to just how deep the legacy of segregation runs within Los Angeles, and how many barriers must be overcome for all those it has touched to be truly uplifted.

"Destination" might imply an end point, but the work is just getting underway.

***

I will be following up on this story with an essay compiling residents' feelings about Crenshaw. If you'd like to share your story with me, reach me at sahra(at)streetsblog.org or find me on twitter or facebook.

Destination Crenshaw will break ground later this spring and be completed some time in early 2020, ahead of the opening of the Crenshaw Line (anticipated for later that year). Visit the Destination Crenshaw website to learn more about the project, the team, and the advisory committee, to join the mailing list, and to keep up with calls for artists.