To get ready for the 2028 Olympics, the Metro Board wants to accelerate projects - mostly to accelerate highway projects. The initiative is called 28 by 2028. Metro's board tasked Metro staff with, in the words of boardmember Mike Bonin, doing "something impossible" - finding an estimated $42.9 billion to pay for project acceleration.

Metro's staff report on funding Olympics project acceleration is ambitiously titled, "The Re-Imagining of L.A. County: Mobility, Equity, and the Environment." The recommendations do not not shy away from big ideas. At yesterday's board meeting, Metro CEO Phil Washington said implementing the proposal would require "radical steps to disrupt the current paradigm."

The proposal recommends against borrowing lots of money, raising transit fares, canceling bike-share, postponing bus electrification, postponing implementation of NextGen bus service re-organization, or skipping some needed "unfunded ancillary efforts." Those ancillary efforts - referred to as "sacred cows" during yesterday's meeting - include the 210 Freeway barrier wall, rail yards and rail operations center upgrades, and a handful of other unfunded projects needed for transit service.

The proposal does recommend congestion pricing, "new mobility fees" on ride-hail and shared mobility devices, raising additional advertising revenues, and seeking more money from the state and federal governments.

Most of the Metro board discussion and media attention has been on Metro's recommendation to further study how to implement congestion pricing. Congestion pricing is the bigger, more contentious issue, but not what this article will focus on. (See earlier SBLA pieces on the benefits of congestion pricing, and why the push for Olympic acceleration has some flaws.)

This article focuses on Metro staff's less talked about proposal to charge "new mobility fees."

This primarily refers to fees for ride-hailing - Uber, Lyft - also called Transportation Network Companies, or TNCs. The proposal also recommends fees for private shared mobility devices: e-scooters, e-bikes, and bike-share.

Ride-Hail Fees

A recent University of Kentucky study linked transit ridership declines to the rise of ride-hail. That research showed TNCs decrease rail ridership by 1.29 percent per year and decrease bus ridership by 1.7 percent per year. Another recent study, by Bruce Shaller, showed that TNCs do not reduce car ownership. Other studies found that, in San Francisco and New York, ride-hail worsens urban congestion.

As Metro looks to raise revenue while reducing congestion and single-occupancy driving, then ride-hail is one place to improve the situation.

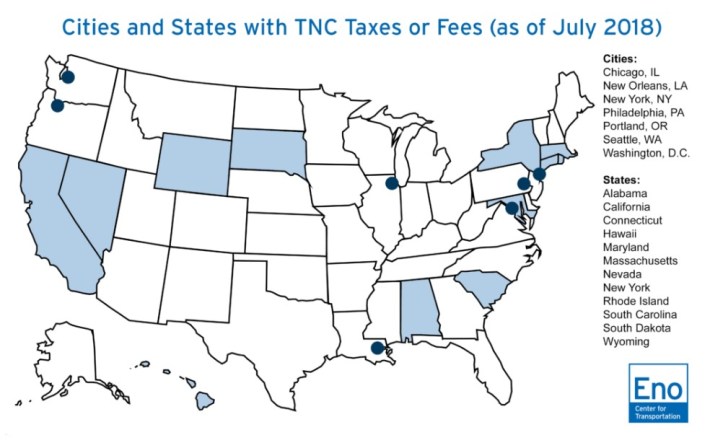

Various states and municipalities already have TNC fees. These are listed in a 2018 report by the Eno Institute, and summarized in the Metro staff report. Some places charge a flat per-trip fee, for example Chicago charges $0.67 per trip. Some places charge a percentage of the overall fare revenue, for example the state of California charges 0.33 percent, which goes to the Public Utilities Commission.

In addition to generating money for transit and highway projects, Metro could design TNC fees to advance policy goals. Examples of this include structuring fees that would:

- improve wheelchair access - some CA state TNC money goes toward this under S.B. 1376

- improve equity - such as encouraging service to under-served areas

- encourage shared rides

- encourage less polluting vehicles

- discourage congestion

Metro staff estimate that collecting new TNC fees could generate anywhere from $25-$350 million annually in L.A. County. In California, TNCs are regulated by the state Public Utilities Commission, so for Metro to enact new TNC fees, it would likely require some kind of state approval, possibly in the form of enabling legislation.

Shared Mobility Device Fees

The Metro staff report also recommends raising revenue from private shared mobility devices: e-scooters, e-bikes, and dockless bike-share. To date, these devices have been regulated by local cities, including Santa Monica and Los Angeles. The report cites the city of Santa Monica's shared device revenue estimated at $89,000 per month. Similar to TNC fees, device fees could also be structured to advance policy goals, such as favoring service for under-served areas and encouraging physical activity.

Metro's information on mobility device fees is less detailed, as the devices are relatively new, though the rough estimate of countywide revenue would be as high as $58 million per year.

New Mobility Fees Easier Politically

Metro board approval of new mobility fees looks much easier than congestion pricing. Several Metro boardmembers are vocal about reining in these disruptive new mobility operations.

County Supervisor Kathryn Barger proposed that e-scooter operations cease and desist in unincorporated county areas. Yesterday, Barger called congestion pricing fees "punitive" and asked about "imposing fees on bike riders."

L.A. City Councilmember Paul Krekorian has been critical of the lack of regulations on TNCs. At yesterday's meeting, Krekorian called TNC fees "long overdue" and criticized TNCs for increasing congestion.

Krekorian raised a jurisdictional concern that applies to both congestion pricing and new mobility fees. While Metro is looking to raise new revenues at the county level, new fees would be for activities taking place in specific cities - such as congestion pricing for a downtown cordon taking place in the city of L.A. on streets operated and maintained by the city. Similarly, freeway corridor charges would take place on freeways operated and maintained by Caltrans, a state agency. At a minimum, this presents challenges in shared governance and coordination. It also means that non-Metro jurisdictions could justifiably insist on some share of revenues.

The Metro board postponed approving the Metro staff recommendation, instead looking to further discuss various revenue options before even proceeding with feasibility studies. The proposal is scheduled for more discussion at next month's board committee meetings.

Readers - do you think that new mobility fees make good sense for increasing Metro revenue? How would fees be structured to best benefit mobility, equity, health, and the environment?