"Queremos vender sin tener miedo," (We want to able to vend without fear.) South Central street vendor Belén Ortiz told the councilmembers present at the joint meeting of the Public Works and Gang Reduction, Economic Development, and Arts, Entertainment, Parks, and River Committees Tuesday afternoon.

The first of a number of vendors who would stand to speak, she urged them to send the draft ordinance authorizing the creation of a sidewalk vending program and a just permit system to the full council for a historic vote Wednesday morning (today).

Even with the decriminalization of sidewalk vending last year, the lack of a formal ordinance meant street vendors were still experiencing harassment from law enforcement, racking up hefty fines they struggled to pay off, and worrying about deportation. It was eating into their livelihoods and making them afraid of losing everything every time they set up their goods.

"Por favor..." she implored the councilmembers, "Queremos salir de la sombra." (Please, we want to come out of the shadows.)

The permit system she was there to advocate for was one of two options the City Attorney's office had embedded in the draft ordinances up for discussion.

The other - a regulatory model which would have only required compliance with regulations - went almost without mention by the speakers. Because it wouldn't require permits, it would not have generated funding for a monitoring and compliance program, making it much less attractive to the city.

Turns out a regulatory model is also less attractive to vendors.

It doesn't legitimize their livelihoods or give them a pathway into the formal economy - something they have actively campaigned for going on ten years now - the way a permit system does. It squelches opportunities for incentives to be used to encourage vendors to sell healthier food. And it limits opportunities for regulators to provide technical assistance to help bring vendors into compliance.

Given the general consensus around the importance of a permit program for the vendors (and the absence of details regarding what the permit process would ultimately entail), those speaking on Tuesday turned their attention to the final adjustments needed to make the draft ordinance, the rules and regulations proposed by the Bureau of Street Services, and the rules proposed for vending in parks more responsive to vendors' realities.

Members of the Los Angeles Street Vendor Campaign touched on points raised in their letters to the councilmembers asking that the vending program and the regulations governing vending in parks

- allow permits to better describe the mode of vending (e.g. fixed location or mobile);

- offer incentives for vendors to sell healthy food;

- provide for an inclusive process by which special vending districts can be created in areas like the Piñata District, MacArthur Park, 47th (at Main), and along Hollywood Boulevard;

- discourage the designation of "no-vending" zones (in line with S.B 946, which requires that any restrictions placed upon vendors be explicitly tied to “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns");

- reduce the 500-foot buffer proposed around "no-vending" zones (e.g. the Hollywood Walk of Fame, event venues, etc.), and farmers markets and swap meets;

- decrease the 20-foot buffer proposed around "the entrance way to any building" (something which could effectively prohibit vending on entire blocks);

- not call upon the Bulky Item ordinance as a backdoor way to ban vending (as was done along the Hollywood Walk of Fame);

- not expand the authority of the Bureau of Street Services (BSS) to confiscate vendors' property;

- allow vending, including stationary vending, in city parks like Echo Park and Leimert Park (where proposed regulations would severely curtail vending);

- reduce the 250-foot buffer proposed around structures within parks (restroom, rec center, playground, etc. - something that would effectively put most parks off limits);

- not ban vendors from parks during events (movie nights, concerts, etc.); and

- not limit vendors in parks to two per acre.

Many of the vendors who spoke underscored the importance of being able to vend in peace to their own well-being as well as the survival of their families. Others, including two women from Leimert Park, spoke of how integral vendors were to uplifting the area's culture and staking out space for celebration of the African diaspora. It was unthinkable, said one, that they would be banned from neighborhoods or park spaces where they had connected children and families to community and culture for decades.

Despite these concerns, thanks to the passage of the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act (S.B. 946) earlier this year, vendors had fewer complaints than they might otherwise have had.

The bill, which legalizes street vending statewide and allows cities to establish permit programs governing the practice, effectively does away with some of the more onerous requirements the city had been looking to impose on vendors, including limiting vendors to two per block in commercial districts, limiting vendor access to particular communities, and restricting vending in parks.

Other elements of the L.A.'s original draft ordinance remain the same: vending would still be restricted in residential areas and food vendors would still be expected to comply with health regulations.

More broadly, however, the bill tips the scales ever so slightly toward the vendors by overriding the capacity of communities to exert excessive local control over the streets and public spaces vendors can access. It prohibits caps on the number of vendors within a city, prohibits the limiting of vendors to designated areas within communities, prohibits requirements that vendors first obtain permission from nongovernmental entities or individuals to access a site, and requires that any restrictions placed upon vendors be explicitly tied to “objective health, safety, or welfare concerns.”

That power shift elicited grumbling from several councilmembers over the past several weeks. They appeared displeased about losing the ability to limit vending in their districts, having to revisit restrictions they'd worked to put in place, and/or having to scramble to get an ordinance on the books before S.B. 946 takes effect on January 1, 2019.

It also appears to have prompted Hollywood stakeholders to make more extreme claims about "safety" concerns in their effort to secure the banishment of vendors from the Walk of Fame. Leron Gubler, retired president of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce called councilmembers' attention to a photo of a vendor he declared to be not only "blocking access to a fire hydrant and a city trash can" but also "smoking marijuana and talking on his cellphone and manning a hot grill that is directly exposed to passing crowds.” A few days prior, Kerry Morrison of the Hollywood BID had made a similar case via twitter for the exemption of Hollywood Boulevard by pointing to the vendors as presenting the safety hazard (not the width of the boulevard or the cars that speed along it).

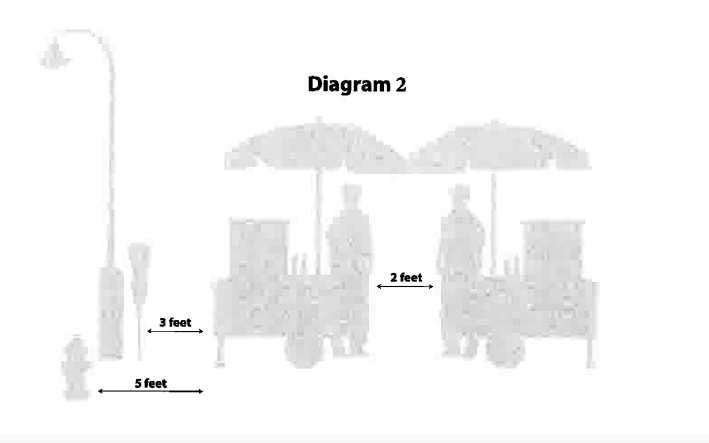

Michael Shilstone of the Central City Association also raised the question of "safety," arguing that the two feet BSS recommended between vendors was not enough to create a safe pedestrian environment.

The Bureau of Street Services and the councilmembers, for their part, seemed committed to working within the constraints of S.B. 946.

The two feet required between vendors, for example, essentially struck a balance between genuine safety concerns, ADA compliance, and adherence to the spirit of the law, BSS representatives argued.

The only area that remained a touchstone for debate was that of how to handle vending in parks.

While Councilmember Mitch O'Farrell asked that the no-vending buffer around structures within parks be reduced from 250 to 100 feet, he also seemed intent on significantly limiting vendor access to parks in other ways (and to Echo Park, in particular). Asking if lakes and forests within parks counted toward the acreage used to calculate how many vendors could set up in a space, he spoke of the possibility of as many as 64 vendors taking over Echo Park. Such a scenario, he argued, was in direct conflict with the mission of parks to create active and passive spaces for Angelenos to enjoy.

Earlier in the hearing, a vendor from Exposition Park had decried the two-vendor-per-acre rule, saying that he and his colleagues worked together to determine how to work the park and never blocked passage or interfered with people's access to park spaces.

But this and the extent to which vendors are, for many Angelenos, integral to a positive park experience, seemed to get lost in the discussion.

Instead, Michael Shull, the general manager of the Recreation and Parks Department, countered that it was difficult to come up with a one-size-fits-all policy for vending in parks, given the city's great diversity in green spaces. The proposed two-per-acre rule was a result of the department's effort to find a happy medium of sorts, given that over 100 of the city's parks are smaller than one acre and more than one vendor there would make little sense. [See the list of parks and their acreage here.]

Councilmembers wrapped the hearing with a discussion of the enforcement of the program. BSS has proposed a staff of 28 to work ten hours a day, seven days a week monitoring overall compliance. For Councilmember Joe Buscaino, a former law enforcement officer, that wasn't nearly enough. He was also dissatisfied with BSS' plan to divide the city into four quadrants and to focus on monitoring "hot spots." Much would be missed by such an approach, he argued.

BSS staff agreed their proposal was imperfect, but explained that was also by design. They would begin with 28 staff and, as the program was finalized and implemented over the course of the coming year, get a better handle on what their staffing and enforcement needs would be and adjust accordingly.

As the hearing drew to a close, councilmembers congratulated the committee members and advocates alike for their dedication to moving this historic ordinance forward over the years.

It was indeed a long time coming.

And it's unclear how much longer the ordinance would have languished if S.B. 946 had not passed.

Despite a decade of advocacy by the Los Angeles Street Vendor Campaign (LASVC) and years' worth of fits and starts in the council, it took the election of Donald Trump to galvanize councilmembers into more concrete action. Declaring their intention to assuage immigrant communities' fears and protect them against deportation for minor infractions, a December, 2016, motion aimed at decriminalizing the practice and resurrecting a 2013 effort to cobble together an ordinance launched a new flurry of activity.

Believing their moment had finally come, vendors rallied to offer heart-wrenching testimony about how vulnerable they were without legal protections and how often they were stripped of their livelihoods.

And then nothing happened.

Well, that's not exactly true - the council moved to decriminalize vending in February of 2017.

But the promised ordinance was nowhere to be seen, and the only voices that seemed to have any real weight in the conversation were those of the business districts and wealthier communities lobbying for the right to keep vendors out of their neighborhoods. Vendors in the MacArthur Park area were reporting more intense crackdowns as 2017 came to a close. And when a draft ordinance was finally posted online a few months ago, it treated vendors as a streetscape amenity rather than an integral part of community life.

That the vendors have had the tenacity to keep pushing to be heard for so long, despite the lost income and potential danger speaking up could pose, underscores the significance of legalization for them.

It is indeed time they were finally able to come out of the shadows, vend without fear, and be celebrated for their singular contributions to community-building and street life.

Follow live updates on today's city council hearing on twitter. See past coverage of the issue below.

- August 22, 2018: Bill Legalizing Sidewalk Vending Statewide Moves Through Legislature, Awaits Governor's Approval

- July 25, 2018: Proposed Ordinance Treats Street Vendors as Streetscape Amenities Rather than Community Assets

- June 27, 2018: You Can’t Plan Mexican Hot Chocolate: How Monique López Deploys a Justice Lens in Her Engagement of Street Vendors (The case of Metro's MacArthur Park station vending district and the problems it has caused for non-participants in the program)

- April 6, 2018: Elotero Benjamín Ramírez Assaulted for Second Time in a Year

- January 12, 2018: L.A.’s Street Vending Proposal Is Unconstitutional And Unwise (by Salvador E. Pérez and Adam S. Sieff)

- December 13, 2016: Committee Debates Framework for Sidewalk Vending Ordinance; Vending Takes Step Closer to Legalization