In downtown Cleveland Saturday night, a driver high on heroin struck and killed Jenasia Summers, 21, as she rode an electric scooter. But instead of questioning why Cleveland streets are so dangerous, the local press has responded by painting scooters as a safety hazard.

The driver, 19-year-old Scott McHugh, struck Summers from behind while traveling "well in excess" of the 25 mph speed limit, according to police reports cited by Cleveland.com. He told police he'd snorted heroin in a parking lot before getting behind the wheel, and he's currently facing charges for aggravated vehicular homicide.

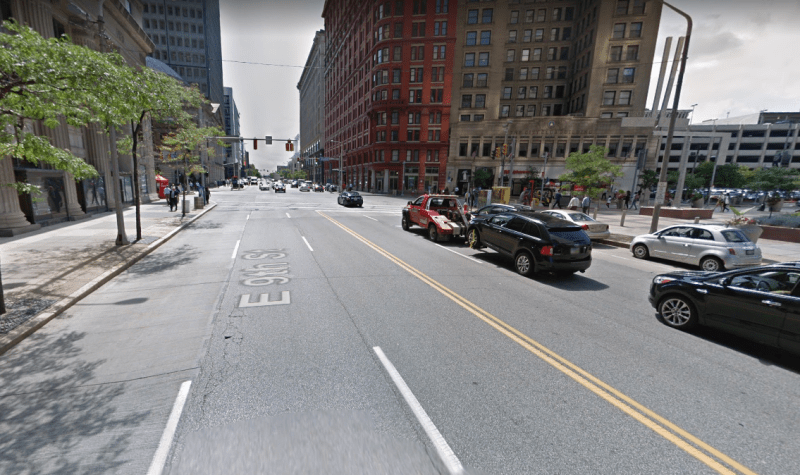

Summers was riding on East 9th Street, which runs through the heart of downtown Cleveland. The street is set up purely for motor vehicle movement, with six moving lanes but no bike lanes. If the city had provided dedicated lanes for people riding bikes and scooters, Summers would probably still be alive.

But the initial response in the local press was not to question Cleveland's dangerous, car-centric street design. It was to cast aspersions on scooters.

"Is use of scooters a cause for concern?" tweeted Cleveland.com. Reporter Jane Morice wrote: "The scooters have been known to cause injuries to their riders in 32 other American cities where they've appeared over the past year."

Scooters have been in the local headlines because the city recently told the start-up Bird to remove a fleet of 100 vehicles from public streets. Summers was not riding a Bird -- she had rented an Icon scooter from a shop downtown. But whatever vehicle she was riding, it's less relevant to this crash than Cleveland's failure to make streets safer for walking, biking, or scooting.

While the city has recently made some progress on bike infrastructure, downtown is still practically devoid of bike lanes. Power players like the Downtown Cleveland Alliance, a coalition of property owners that essentially dictate public policy for the area, have resisted adding bike infrastructure. Even as downtown becomes increasingly residential, with a population of 15,000, the Alliance prefers to cater to suburban office workers who drive in and out.

"We don't get much support for [bike infrastructure] from DCA," said Jacob van Sickle, executive director of Bike Cleveland.

East 9th Street is a classic example of how the city's cars-first approach puts people in danger. For about 30-60 minutes on weekday mornings and evenings, it carries a lot of car commuters. The city likes to keep it wide and clear for these drivers seeking quick access to freeway ramps, going so far as to station police at key intersections to direct rush hour traffic.

But at all other times, especially at night, East 9th Street is mostly empty, and its excessive width encourages speeding.

Popular bars are located on East 9th Street. At the time Summers was struck -- 10 p.m. on Saturday night -- it would have been bustling with nightlife. But because the street is designed explicitly for people who drive to work, Summers was vulnerable.

In Cleveland, like other cities, the first impulse of the local government was to ban Bird's scooters. But that's not going to solve the problems that led to the death of Jenasia Summers, not to mention the thousands of other vulnerable people struck by drivers on American streets each year.

Cleveland could have prevented this loss of life if only city officials took their own street safety policies seriously. The city passed a "Complete and Green Streets ordinance" back in 2011, but four years later, progress remained slow, the Plain Dealer reported.

Portions of East 9th Street were resurfaced in 2013 and 2016, and under the Complete Streets ordinance, those paving projects should have triggered an evaluation of the street design and the addition of bike lanes. But the city kept the same old car-centric design.

"When they repaved it a few years ago, we talked to the city about adding bike lanes," said van Sickle. "They said, 'That's one of our main arterials, so we need to maximize traffic.'"

Now a young woman is dead.