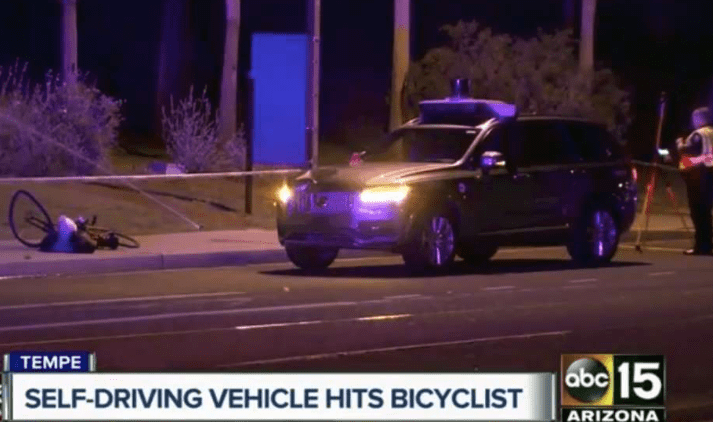

Tragically, a self-driven vehicle (autonomous vehicle, or AV) killed a woman walking across the street in Tempe, Arizona, earlier this week. What can we learn from this and how should policymakers react?

Safety experts will examine the crash to determine what went wrong. I’ve looked at the video and Google Street View and have read many of the articles describing what took place. Without understanding the location and the victim’s path of travel better, it’s difficult to ascertain as much as I would like. But here are a few observations:

- The crash occurred while the victim crossed a road designed for high speeds in an area that has quite a bit of open desert mixed with a few hopscotch developments.

- Some better land use planning that avoids hopscotch development in favor of developing within or next to existing developments, coupled with streets designed for slower speeds, would help avoid many crashes and their severity. It might have helped to either avoid this crash or reduce its severity.

- The street was not well lighted, but we wouldn’t expect that in an area that is mostly open desert. Again, better land use planning might have made a difference.

- It appears from the video that the Uber car didn’t slow down or change course. The driver wasn’t paying attention, relying on the AV function to react. It looks as though the AV technology failed to detect the victim, to brake, or to swerve.

- It is difficult to know if a human driver would have hit the victim, given the speed of the road and the poor lighting. But it appears that a human might have at least had a chance to brake or swerve. The crash might have been avoided or may have been less severe with a human driver.

- The Uber car was essentially functioning at what is defined as “level 3 autonomous.” That means it drives itself most of the time but requires human intervention at some points. The driver did not intervene. Some AV supporters suggest that we skip from level 2 (full-time human driver with some AV functions like brake assist, park assist, lane assist, adaptive cruise control, etc.) directly to level 4 (no driver, but limited geographically as to where it can travel). The thinking is that, as seems to be the case here, when the driver becomes too dependent on the AV function he/she may fail to take the wheel when needed.

- Not all AV technology is equal. It is possible that another car, another set of lidar, radar, or cameras could have done a better job.

We know that 94 percent of crashes are caused by human error. Hypothetically, when AVs have the bugs worked out, most of those crashes should be eliminated. The time to let AVs have free run of our streets and highways isn’t when they are crash-free. It is when they are safer than today’s human-driven vehicles that kill 40,000 people per year in the US and injure well over 2 million. The trick is knowing when that is. Until many millions of miles are traveled with AVs, we won’t have enough data to ascertain that. In the meantime, prudent policy should allow graduated testing that ramps up to a wider range of environments as we gain confidence in AVs’ capabilities.

Recently both the Federal Department of Transportation and the House of Representatives have taken a hands-off approach by allowing AVs to test with few restrictions. We need to proceed more carefully. At least some AVs haven’t proven to be safe enough to operate on at least some streets. Equipment requirements should ensure a greater level of safety. It makes sense to require black boxes in each AV that record every crash to be reported so that we can learn and correct deficiencies. We should ensure that AVs can detect pedestrians and bicyclists. The equipment safety experts can add to this list. And all of the principles of equity, living streets, vision zero, new urbanism, and smart growth will still apply.

In the long run, AVs will probably be much safer than human-driven vehicles. They also have potential to bring enormous benefits to access, equity, health, community livability, reduction of greenhouse gases and more. Because of this, calls to stop all testing and insistence on perfection are misplaced. AVs will have crashes, especially in the early stages. Because of the potential enormous benefits to society, we need to let this nascent technology proceed through its learning curve. But the safety and other benefits will only occur with the right public policies in place. Given this, we should proceed to test and develop AV technology. But let’s proceed more cautiously.

Ryan Snyder is Principal with Transpo Group. Snyder is a member of the Bicycle Technical Committee and the Autonomous Vehicle Task Force of the United States National Uniform Traffic Device Committee. He coordinated the Autonomous Vehicle Policy Framework Summit that brought 100 national experts together to advance the policy discussion on how to prepare for a future with autonomous vehicles. Snyder serves on the faculty at the UCLA Urban Planning Department. Follow Snyder on Twitter.